Liquidambar Styraciflua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living in Drylands: Functional Adaptations of Trees and Shrubs to Cope with High Temperatures and Water Scarcity

Review Living in Drylands: Functional Adaptations of Trees and Shrubs to Cope with High Temperatures and Water Scarcity José Javier Peguero-Pina 1,2,* , Alberto Vilagrosa 3 , David Alonso-Forn 1 , Juan Pedro Ferrio 1,4 , Domingo Sancho-Knapik 1,2 and Eustaquio Gil-Pelegrín 1 1 Unidad de Recursos Forestales, Centro de Investigación y Tecnología Agroalimentaria de Aragón (CITA), Avda. Montañana 930, 50059 Zaragoza, Spain; [email protected] (D.A.-F.); [email protected] (J.P.F.); [email protected] (D.S.-K.); [email protected] (E.G.-P.) 2 Instituto Agroalimentario de Aragón -IA2- (CITA-Universidad de Zaragoza), 50059 Zaragoza, Spain 3 Mediterranean Center for Environmental Studies (Fundación CEAM), Joint Research Unit University of Alicante—CEAM, Univ. Alicante, PO Box 99, 03080 Alicante, Spain; [email protected] 4 Aragon Agency for Research and Development (ARAID), E-50018 Zaragoza, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-976-716-974 Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 23 September 2020 Abstract: Plant functioning and survival in drylands are affected by the combination of high solar radiation, high temperatures, low relative humidity, and the scarcity of available water. Many ecophysiological studies have dealt with the adaptation of plants to cope with these stresses in hot deserts, which are the territories that have better evoked the idea of a dryland. Nevertheless, drylands can also be found in some other areas of the Earth that are under the Mediterranean-type climates, which imposes a strong aridity during summer. In this review, plant species from hot deserts and Mediterranean-type climates serve as examples for describing and analyzing the different responses of trees and shrubs to aridity in drylands, with special emphasis on the structural and functional adaptations of plants to avoid the negative effects of high temperatures under drought conditions. -

Conservation Assessment for the Bigleaf Snowbell (Styrax Grandifolius Ait.)

Conservation Assessment for the Bigleaf Snowbell (Styrax grandifolius Ait.) Steven R. Hill, Ph.D. Division of Biodiversity and Ecological Entomology Biotic Surveys and Monitoring Section 1816 South Oak Street Champaign, Illinois 61820 Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Eastern Region (Region 9), Shawnee and Hoosier National Forests INHS Technical Report 2007 (65) Date of Issue: 17 December 2007 Cover photo: Styrax grandifolius Ait., from the website: In Bloom – A Monthly Record of Plants in Alabama; Landscape Horticulture at Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama. http://www.ag.auburn.edu/hort/landscape/inbloomapril99.html This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. 2 Conservation Assessment for the Bigleaf Snowbell (Styrax grandifolius Ait.) Table of Contents -

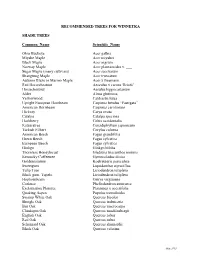

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Beaver Damage Prevention and Control Methods

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA9085 Beaver Damage Prevention and Control Methods Rebecca McPeake The American beaver (Castor The purpose of this fact sheet is Professor - canadensis), our largest North Ameri to provide information about alterna Extension Wildlife can rodent, is nature’s equivalent of tive control methods to address these a habitat engineer (Figure 1). Beaver issues. Because wildlife laws are sub Specialist create ponds and wetlands used by ject to change, refer to a local wildlife waterfowl, shorebirds, mink (Mustela officer, an Arkansas hunting guidebook vison), muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus), or an Arkansas Game and Fish Com river otters (Lutra spp.), fish, amphib mission office (800-364-4263, www ians, aquatic plants and other living .agfc.com) for current information. species. Beaver ponds generally slow the water flow from drainage areas Description and and alter silt deposition, which creates new habitat. During drought Life History conditions, beaver ponds create water holes for livestock and wildlife, partic The beaver is a large, stocky- ularly wood ducks (Aix sponsa) and appearing rodent, generally 35 to river otters. However, their engineer 40 inches long from head to tail. It ing feats cause problems when they: has a broad, flat paddle-shaped tail, short ears and generally brown fur. • Flood homes, roads and croplands. The beaver ’s tail is used as a rudder • Dam canals, drainages and pipes, while swimming and is slapped which inhibits water control. against the water as a danger signal. The beaver ’s four large front teeth • Girdle and fell valuable trees. -

Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar Styraciflua L

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2016) 5(1): 306-317 ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 5 Number 1(2016) pp. 306-317 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article http://dx.doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2016.501.029 Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar styraciflua L. (Altingiaceae) Graziele Francine Franco Mancarz1*, Ana Carolina Pareja Lobo1, Mariah Brandalise Baril1, Francisco de Assis Franco2 and Tomoe Nakashima1 1Pharmaceutical ScienceDepartment, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil 2Coodetec Desenvolvimento, Produção e Comercialização Agrícola Ltda, Cascavel, PR, Brazil *Corresponding author A B S T R A C T K e y w o r d s The genus Liquidambar L. is the best-known genus of the Altingiaceae Horan family, and species of this genus have long been used for the Liquidambar treatment of various diseases. Liquidambar styraciflua L., which is styraciflua, popularly known as sweet gum or alligator tree, is an aromatic deciduous antioxidant tree with leaves with 5-7 acute lobes and branched stems. In the present activity, study, we investigated the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of aerial antimicrobial parts of L.styraciflua. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the activity, microdilution methodology. The DPPH and phosphomolybdenum methods microdilution method, were used to assess the antioxidant capacity of the samples. The extracts DPPH assay showed moderate or weak antimicrobial activity. The essential oil had the lowest MIC values and exhibited bactericidal action against Escherichia Article Info coli, Enterobacter aerogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. The ethyl acetate fraction and the butanol fraction from the bark and stem showed the best Accepted: antioxidant activity. -

What Is a Tree in the Mediterranean Basin Hotspot? a Critical Analysis

Médail et al. Forest Ecosystems (2019) 6:17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0170-6 RESEARCH Open Access What is a tree in the Mediterranean Basin hotspot? A critical analysis Frédéric Médail1* , Anne-Christine Monnet1, Daniel Pavon1, Toni Nikolic2, Panayotis Dimopoulos3, Gianluigi Bacchetta4, Juan Arroyo5, Zoltán Barina6, Marwan Cheikh Albassatneh7, Gianniantonio Domina8, Bruno Fady9, Vlado Matevski10, Stephen Mifsud11 and Agathe Leriche1 Abstract Background: Tree species represent 20% of the vascular plant species worldwide and they play a crucial role in the global functioning of the biosphere. The Mediterranean Basin is one of the 36 world biodiversity hotspots, and it is estimated that forests covered 82% of the landscape before the first human impacts, thousands of years ago. However, the spatial distribution of the Mediterranean biodiversity is still imperfectly known, and a focus on tree species constitutes a key issue for understanding forest functioning and develop conservation strategies. Methods: We provide the first comprehensive checklist of all native tree taxa (species and subspecies) present in the Mediterranean-European region (from Portugal to Cyprus). We identified some cases of woody species difficult to categorize as trees that we further called “cryptic trees”. We collected the occurrences of tree taxa by “administrative regions”, i.e. country or large island, and by biogeographical provinces. We studied the species-area relationship, and evaluated the conservation issues for threatened taxa following IUCN criteria. Results: We identified 245 tree taxa that included 210 species and 35 subspecies, belonging to 33 families and 64 genera. It included 46 endemic tree taxa (30 species and 16 subspecies), mainly distributed within a single biogeographical unit. -

Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2016 Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi Hanna M. Miller University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Hanna M., "Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi" (2016). Honors Theses. 389. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/389 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi by Hanna Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biological Sciences May 2016 ii Approved by _________________________________ Mac H. Alford, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Professor of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Shiao Y. Wang, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii Abstract The North American Coastal Plain contains some of the highest plant diversity in the temperate world. However, most of the region has remained unstudied, resulting in a lack of knowledge about the unique plant communities present there. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

United States Department of Agriculture

Pest Management Science Pest Manag Sci 59:788–800 (online: 2003) DOI: 10.1002/ps.721 United States Department of Agriculture—Agriculture Research Service research on targeted management of the Formosan subterranean termite Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae)†‡ Alan R Lax∗ and Weste LA Osbrink USDA-ARS-Southern Regional Research Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Abstract: The Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki is currently one of the most destructive pests in the USA. It is estimated to cost consumers over US $1 billion annually for preventative and remedial treatment and to repair damage caused by this insect. The mission of the Formosan Subterranean Termite Research Unit of the Agricultural Research Service is to demonstrate the most effective existing termite management technologies, integrate them into effective management systems, and provide fundamental problem-solving research for long-term, safe, effective and environmentally friendly new technologies. This article describes the epidemiology of the pest and highlights the research accomplished by the Agricultural Research Service on area-wide management of the termite and fundamental research on its biology that might provide the basis for future management technologies. Fundamental areas that are receiving attention are termite detection, termite colony development, nutrition and foraging, and the search for biological control agents. Other fertile areas include understanding termite symbionts that may provide an additional target for control. Area-wide management of the termite by using population suppression rather than protection of individual structures has been successful; however, much remains to be done to provide long-term sustainable population control. An educational component of the program has provided reliable information to homeowners and pest-control operators that should help slow the spread of this organism and allow rapid intervention in those areas which it infests. -

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews With contributions from Anne Boscawen (UK), John Bulmer (UK), Koen Camelbeke (Belgium), John Gammon (UK), Hugh Glen (South Africa), Philippe de Spoelberch (Belgium), Dick van Hoey Smith (The Netherlands), Robert Vernon (UK) and Ulrich Würth (Germany). Affinities, generic distribution and fossil record Liquidambar L. has close taxonomic affinities with Altingia Noronha since these two genera share gum ducts associated with vascular bundles, terminal buds enclosed within numerous bud scales, spirally arranged stipulate leaves, poly- porate (with several pore-like apertures) pollen grains, condensed bisexual inflorescences, perfect or imperfect flowers, and winged seeds. Not surpris- ingly, Liquidambar, Altingia and Semiliquidambar H.T. Chang have now been placed in the Altingiaceae, as originally treated (Blume 1828, Wilson 1905, Chang 1964, Melikan 1973, Li et al. 1988, Zhou & Jiang 1990, Wang 1992, Qui et al. 1998, APG 1998, Judd et al. 1999, Shi et al. 2001 and V. Savolainen pers. comm.). These three genera were placed in the subfamily Altingioideae in Hamamelidaceae (Reinsch 1890, Chang 1979, Cronquist 1981, Bogle 1986, Endress 1989) or the Liquidambaroideae (Harms 1930). Shi et al. (2001) noted that Altingia species are evergreen with entire, unlobed leaves; Liquidambar is deciduous with 3-5 or 7-lobed leaves; while Semiliquidambar is evergreen or deciduous, with trilobed, simple or one-lobed leaves. Cytological studies have indicated that the chromosome number of Liquidambar is 2n = 30, 32 (Anderson & Sax 1935, Pizzolongo 1958, Santamour 1972, Goldblatt & Endress 1977). Ferguson (1989) stated that this chromosome number distinguished Liquidambar from the rest of the Hamamelidaceae with their chromosome numbers of 2n = 16, 24, 36, 48, 64 and 72. -

Styrax Japonicus Japanese Snowbell1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-605 October 1994 Styrax japonicus Japanese Snowbell1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Japanese Snowbell is a small deciduous tree that slowly grows from 20 to 30 feet in height and has rounded canopy with a horizontal branching pattern (Fig. 1). With lower branches removed, it forms a more vase-shaped patio-sized shade tree. The smooth, attractive bark has orange-brown interlacing fissures adding winter interest to any landscape. The white, bell-shaped, drooping flower clusters of Japanese Snowbell are quite showy in May to June. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Styrax japonicus Pronunciation: STY-racks juh-PAWN-ih-kuss Common name(s): Japanese Snowbell Figure 1. Middle-aged Japanese Snowbell. Family: Styracaceae USDA hardiness zones: 6 through 8A (Fig. 2) DESCRIPTION Origin: not native to North America Uses: container or above-ground planter; large Height: 20 to 30 feet parking lot islands (> 200 square feet in size); wide Spread: 15 to 25 feet tree lawns (>6 feet wide); medium-sized parking lot Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a islands (100-200 square feet in size); medium-sized regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); recommended for buffer or less identical crown forms strips around parking lots or for median strip plantings Crown shape: round; vase shape in the highway; near a deck or patio; trainable as a Crown density: moderate standard; small parking lot islands (< 100 square feet Growth rate: slow in size); narrow tree lawns (3-4 feet wide); specimen; Texture: medium sidewalk cutout (tree pit); residential street tree; no proven urban tolerance Availability: grown in small quantities by a small number of nurseries 1. -

Liquidambar Styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia

43 Banisteria, Number 9, 1997 © 1997 by the Virginia Natural History Society An Abnormal Variant of Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia Bruce L. King Department of Biology Randolph Macon College Ashland, Virginia 23005 Leaves of individuals of Liquidambar styraciflua L. Similar measurements were made from surrounding (sweetgum) - are predominantly 5-lobed, occasionally 7- plants in three height classes:, early sapling, 61-134 cm; lobed or 3-lobed (Radford et al., 1968; Cocke, 1974; large seedlings, 10-23 cm; and small seedlings (mostly first Grimm, 1983; Duncan & Duncan, 1988). The tips of the year), 3-8.5 cm. All of the small seedlings were within 5 lobes are acute and leaf margins are serrate, rarely entire. meters of the atypical specimen and most of the large In 1991, I found a seedling (2-3 yr old) that I seedlings and saplings were within 10 meters. The greatest tentatively identified as a specimen of Liquidambar styrac- distance between any two plants was 70 meters. All of the iflua. The specimen occurs in a 20 acre section of plants measured were in dense to moderate shade. In the deciduous forest located between U.S. Route 1 and seedling classes, three leaves were measured from each of Waverly Drive, 3.2 km south of Ladysmith, Caroline ten plants (n = 30 leaves). In the sapling class, counts of County, Virginia. The seedling was found at the middle leaf lobes and observations of lobe tips and leaf margins of a 10% slope. Dominant trees on the upper slope were made from ten leaves from each of 20 plants (n include Quercus alba L., Q.