United States Department of Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

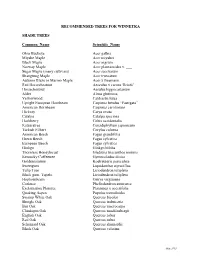

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar Styraciflua L

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2016) 5(1): 306-317 ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 5 Number 1(2016) pp. 306-317 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article http://dx.doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2016.501.029 Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar styraciflua L. (Altingiaceae) Graziele Francine Franco Mancarz1*, Ana Carolina Pareja Lobo1, Mariah Brandalise Baril1, Francisco de Assis Franco2 and Tomoe Nakashima1 1Pharmaceutical ScienceDepartment, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil 2Coodetec Desenvolvimento, Produção e Comercialização Agrícola Ltda, Cascavel, PR, Brazil *Corresponding author A B S T R A C T K e y w o r d s The genus Liquidambar L. is the best-known genus of the Altingiaceae Horan family, and species of this genus have long been used for the Liquidambar treatment of various diseases. Liquidambar styraciflua L., which is styraciflua, popularly known as sweet gum or alligator tree, is an aromatic deciduous antioxidant tree with leaves with 5-7 acute lobes and branched stems. In the present activity, study, we investigated the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of aerial antimicrobial parts of L.styraciflua. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the activity, microdilution methodology. The DPPH and phosphomolybdenum methods microdilution method, were used to assess the antioxidant capacity of the samples. The extracts DPPH assay showed moderate or weak antimicrobial activity. The essential oil had the lowest MIC values and exhibited bactericidal action against Escherichia Article Info coli, Enterobacter aerogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. The ethyl acetate fraction and the butanol fraction from the bark and stem showed the best Accepted: antioxidant activity. -

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews With contributions from Anne Boscawen (UK), John Bulmer (UK), Koen Camelbeke (Belgium), John Gammon (UK), Hugh Glen (South Africa), Philippe de Spoelberch (Belgium), Dick van Hoey Smith (The Netherlands), Robert Vernon (UK) and Ulrich Würth (Germany). Affinities, generic distribution and fossil record Liquidambar L. has close taxonomic affinities with Altingia Noronha since these two genera share gum ducts associated with vascular bundles, terminal buds enclosed within numerous bud scales, spirally arranged stipulate leaves, poly- porate (with several pore-like apertures) pollen grains, condensed bisexual inflorescences, perfect or imperfect flowers, and winged seeds. Not surpris- ingly, Liquidambar, Altingia and Semiliquidambar H.T. Chang have now been placed in the Altingiaceae, as originally treated (Blume 1828, Wilson 1905, Chang 1964, Melikan 1973, Li et al. 1988, Zhou & Jiang 1990, Wang 1992, Qui et al. 1998, APG 1998, Judd et al. 1999, Shi et al. 2001 and V. Savolainen pers. comm.). These three genera were placed in the subfamily Altingioideae in Hamamelidaceae (Reinsch 1890, Chang 1979, Cronquist 1981, Bogle 1986, Endress 1989) or the Liquidambaroideae (Harms 1930). Shi et al. (2001) noted that Altingia species are evergreen with entire, unlobed leaves; Liquidambar is deciduous with 3-5 or 7-lobed leaves; while Semiliquidambar is evergreen or deciduous, with trilobed, simple or one-lobed leaves. Cytological studies have indicated that the chromosome number of Liquidambar is 2n = 30, 32 (Anderson & Sax 1935, Pizzolongo 1958, Santamour 1972, Goldblatt & Endress 1977). Ferguson (1989) stated that this chromosome number distinguished Liquidambar from the rest of the Hamamelidaceae with their chromosome numbers of 2n = 16, 24, 36, 48, 64 and 72. -

Liquidambar Styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia

43 Banisteria, Number 9, 1997 © 1997 by the Virginia Natural History Society An Abnormal Variant of Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia Bruce L. King Department of Biology Randolph Macon College Ashland, Virginia 23005 Leaves of individuals of Liquidambar styraciflua L. Similar measurements were made from surrounding (sweetgum) - are predominantly 5-lobed, occasionally 7- plants in three height classes:, early sapling, 61-134 cm; lobed or 3-lobed (Radford et al., 1968; Cocke, 1974; large seedlings, 10-23 cm; and small seedlings (mostly first Grimm, 1983; Duncan & Duncan, 1988). The tips of the year), 3-8.5 cm. All of the small seedlings were within 5 lobes are acute and leaf margins are serrate, rarely entire. meters of the atypical specimen and most of the large In 1991, I found a seedling (2-3 yr old) that I seedlings and saplings were within 10 meters. The greatest tentatively identified as a specimen of Liquidambar styrac- distance between any two plants was 70 meters. All of the iflua. The specimen occurs in a 20 acre section of plants measured were in dense to moderate shade. In the deciduous forest located between U.S. Route 1 and seedling classes, three leaves were measured from each of Waverly Drive, 3.2 km south of Ladysmith, Caroline ten plants (n = 30 leaves). In the sapling class, counts of County, Virginia. The seedling was found at the middle leaf lobes and observations of lobe tips and leaf margins of a 10% slope. Dominant trees on the upper slope were made from ten leaves from each of 20 plants (n include Quercus alba L., Q. -

Wood from Midwestern Trees Purdue EXTENSION

PURDUE EXTENSION FNR-270 Daniel L. Cassens Professor, Wood Products Eva Haviarova Assistant Professor, Wood Science Sally Weeks Dendrology Laboratory Manager Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University Indiana and the Midwestern land, but the remaining areas soon states are home to a diverse array reforested themselves with young of tree species. In total there are stands of trees, many of which have approximately 100 native tree been harvested and replaced by yet species and 150 shrub species. another generation of trees. This Indiana is a long state, and because continuous process testifies to the of that, species composition changes renewability of the wood resource significantly from north to south. and the ecosystem associated with it. A number of species such as bald Today, the wood manufacturing cypress (Taxodium distichum), cherry sector ranks first among all bark, and overcup oak (Quercus agricultural commodities in terms pagoda and Q. lyrata) respectively are of economic impact. Indiana forests native only to the Ohio Valley region provide jobs to nearly 50,000 and areas further south; whereas, individuals and add about $2.75 northern Indiana has several species billion dollars to the state’s economy. such as tamarack (Larix laricina), There are not as many lumber quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), categories as there are species of and jack pine (Pinus banksiana) that trees. Once trees from the same are more commonly associated with genus, or taxon, such as ash, white the upper Great Lake states. oak, or red oak are processed into In urban environments, native lumber, there is no way to separate species provide shade and diversity the woods of individual species. -

Water's Park Tree Inventory and Assessment

Arborist’s Report Tree Inventory and Assessment 1 Waters Park Drive San Mateo, CA 94403 Prepared for: Strada Investment Group March 3, 2018 Prepared By: Richard Gessner ASCA - Registered Consulting Arborist ® #496 ISA - Board Certified Master Arborist® WE-4341B ISA - Tree Risk Assessor Qualified CA Qualified Applicators License QL 104230 © Copyright Monarch Consulting Arborists LLC, 2018 1 Waters Park Drive, San Mateo Tree Inventory and Assessment March 3, 2018 Table of Contents Summary............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 2 Background ............................................................................................................2 Assignment .............................................................................................................2 Limits of the assignment ........................................................................................2 Purpose and use of the report ................................................................................3 Observations......................................................................................................... 3 Tree Inventory .........................................................................................................3 Analysis................................................................................................................ -

Phylogeographical Structure of Liquidambar Formosana Hance Revealed by Chloroplast Phylogeography and Species Distribution Models

Article Phylogeographical Structure of Liquidambar formosana Hance Revealed by Chloroplast Phylogeography and Species Distribution Models 1,2, 1, 1 2 1 1, Rongxi Sun y , Furong Lin y, Ping Huang , Xuemin Ye , Jiuxin Lai and Yongqi Zheng * 1 State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, Key Laboratory of Silviculture of the State Forestry Administration, Research Institute of Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing 100091, China; [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (F.L.); [email protected] (P.H.); [email protected] (J.L.) 2 Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Silviculture, College of Forestry, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang 330045, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-6288-8565 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 2 September 2019; Accepted: 29 September 2019; Published: 1 October 2019 Abstract: To understand the origin and evolutionary history, and the geographical and historical causes for the formation of the current distribution pattern of Lquidambar formosana Hance, we investigated the phylogeography by using chloroplasts DNA (cpDNA) non-coding sequences and species distribution models (SDM). Four cpDNA intergenic spacer regions were amplified and sequenced for 251 individuals from 25 populations covering most of its geographical range in China. A total of 20 haplotypes were recovered. The species had a high level of chloroplast genetic variation (Ht = 0.909 0.0192) and a significant phylogeographical structure (genetic differentiation takes into ± account distances among haplotypes (Nst) = 0.730 > population differentiation that does not consider distances among haplotypes (Gst) = 0.645; p < 0.05), whereas the genetic variation within populations (Hs = 0.323 0.0553) was low. -

Northern Pin Oak Quercus Ellipsoidalis

Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Northern Pin Oak Quercus ellipsoidalis Height: 50’ - 70’ Spread: 40’ - 60’ Site characteristics: Full sun, dry to medium moisture, well-drained soils Zone: 4 - 7 Wet/dry: Tolerates dry soils Native range: North Central United States pH: ≤ 7.5 Shape: Cylindrical shape and rounded crown; upper branches are ascending while lower branches are descending Foliage: Dark green leaves in summer, russet-red in fall Other: Elliptic acorns mature after two seasons Additional: Tolerates neutral pH better than pin oak (Quercus palustris) Pests: Oak wilt, chestnut blight, shoestring root rot, anthracnose, oak leaf blister, cankers, leaf spots and powdery mildew. Potential insect pests include scales, oak skeletonizers, leafminers, galls, oak lace bugs, borers, caterpillars and nut weevils. Jesse Saylor, MSU Jesse Saylor, Joseph O’Brien, Bugwood.org Joseph O’Brien, MSU Bert Cregg, Map indicates species’ native range. U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Content development: Dana Ellison, Tree form illustrations: Marlene Cameron. Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Bert Cregg and Robert Schutzki, Michigan State University, Departments of Horticulture and Forestry A smart urban or community landscape has a diverse combination of trees. The devastation caused by exotic pests such as Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight and emerald ash borer has taught us the importance of species diversity in our landscapes. Exotic invasive pests can devastate existing trees because many of these species may not have evolved resistance mechanisms in their native environments. In the recent case of emerald ash borer, white ash and green ash were not resistant to the pest and some communities in Michigan lost up to 20 percent of their tree cover. -

Not Just Urban: the Formosan Subterranean Termite, Coptotermes Formosanus, Is Invading Forests in the Southeastern USA

Biol Invasions https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1899-5 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Not just urban: The Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus, is invading forests in the Southeastern USA Theodore A. Evans . Brian T. Forschler . Carl C. Trettin Received: 13 June 2018 / Accepted: 15 December 2018 Ó Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract Coptotermes formosanus, known in its Charleston, and 115% more in New Orleans. Simi- native China as the ‘House White Ant’, was intro- larly, compared with patches free of C. formosanus, duced to the southeast USA likely in the 1950s, where hollows were 2–3 times larger in infested patches in it is known as the Formosan subterranean termite. In Charleston, and 2–6 times larger in New Orleans. the USA it is best known as a pest of buildings in urban Quercus (oak) and Acer (maple) were the most areas, however C. formosanus also attacks live trees damaged trees in Charleston, whereas Carya (bitternut along streets and in urban parks, suggesting it may be hickory), Taxodium (bald cypress), Nyssa (blackgum) able to invade forests in the USA. A survey of 113 and Liquidamber (sweetgum) were the most damaged forest patches around Charleston South Carolina and in New Orleans. As termite damaged trees are more New Orleans Louisiana, where C. formosanus was likely to die, these differing damage levels between first recorded, found that 37% and 52%, respectively, tree species suggests that C. formosanus may alter were infested. Resistograph measurement of internal community structure in US forests. hollows in tree trunks in forest patches infested with C. -

Env-2018-6903-B

APPENDIX B Tree Report Tree Report Prepared for KPS Studio Jobsite 10810 Vanowen, North Hollywood, Ca Prepared by Mike Parker Certified Arborist WE-3414A P.O. Box 746 Chino, CA 91708 909-590-4100 [email protected] July 24, 2018 Table of Contents Observation & Recommendations 1-2 Tree Inventory Matrix 3 Tree Location Map 4 Conceptual Site Plan 5 Tree Photos 6-13 Tree Report Mike Parker, Certified Arborist WE3414A July 24, 2018 July 24, 2018 KSP Studio c/o Justin J Heacock 23 Orchard #200 | Lake Forest, CA 92630 Dear Mr. Heacock, I performed a site visit to the property located at 10810 Vanowen Street, North Hollywood, CA 91605. My assignment was to look at all the trees on site and determine the following: *Any protected trees that need to be mitigated *Any non-protected trees on-site *Prepare a tree inventory for a CEQA report that is being prepared. The following is a summary of my observations with recommendations. OBSERVATIONS I observed 18 various species of trees located on the north and south sides of the property, (see attached tree inventory sheet). I observed 14 City Trees that appeared to be recently planted; 8 ‘Drake’ Chinese Elm trees located on the north sidewalk; 6 Drake’ Chinese Elm trees on the south sidewalk; and 1 established Crape Myrtle tree located on the east sidewalk area. Some of the newly planted Chinese Elm trees appeared stressed, but the established Crape Myrtle was in good condition. All of the site trees are currently in fair to good condition. In our conversation, you mentioned to me that the property owners are renovating the site and will be removing a number of trees as a result of the new site plan. -

Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Ninety Six National Historic Site

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND PLANT COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR NINETY SIX NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Network Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office November 2003 NatureServe Ninety Six National Historic Site ii NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. A NatureServe Technical Report Prepared for the National Park Service under Cooperative Agreement H 5028 01 0435. Citation: White, Jr., Rickie D. and Tom Govus. 2003. Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Ninety Six National Historic Site. Durham, North Carolina: NatureServe. © 2003 NatureServe NatureServe 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama Street, S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not consitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at www.natureserve.org/explorer. Cover photo: Rain lily (Zephranthes atamasca) blooming in April 2002 along Ninety Six Creek. -

Liquidambar Styraciflua 'Burgundy'

Fact Sheet ST-359 November 1993 Liquidambar styraciflua ‘Burgundy’ ‘Burgundy’ Sweetgum1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION This cultivar of Sweetgum grows in a narrow pyramid to a height of 75 feet and may spread to 50 feet (Fig. 1). The beautifully glossy, star-shaped leaves turn bright red-purple in the fall (USDA hardiness zones 6 and 7) and early winter (USDA hardiness zones 8 and 9). In the fall, leaves are held on the tree longer than the species. It is well adapted to the Deep South. On some trees, particularly in the northern part of its range, branches are covered with characteristic corky projections. The trunk is normally straight and does not divide into double or multiple leaders and side branches are small in diameter on young trees, creating a pyramidal form. The bark becomes deeply ridged at about 25-years-old. Sweetgum makes a nice conical park, campus or residential shade tree for large properties when it is young, developing a more oval or rounded canopy as it grows older as several branches become dominant and grow in diameter. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Liquidambar styraciflua ‘Burgundy’ Pronunciation: lick-wid-AM-bar sty-rass-ih-FLOO-uh Common name(s): ‘Burgundy’ Sweetgum Family: Hamamelidaceae Figure 1. Young ‘Burgundy’ Sweetgum. USDA hardiness zones: 6 through 10A (Fig. 2) Origin: native to North America tree; specimen; residential street tree; no proven urban tolerance Uses: large parking lot islands (> 200 square feet in Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out size); wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); recommended of the region to find the tree for buffer strips around parking lots or for median strip plantings in the highway; reclamation plant; shade 1.