A REVIEW the DROUGHT of 19I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

20 NOV 2Q02 I FXCHA^O'-"> 1 Norfolk Bird Report - 2001 Editor: Giles Dunmore Editorial 95 Review of the Year 98 Wetland Bird Surveys for Breydon and The Wash 1 05 Norfolk Bird Atlas 1 07 Systematic List 1 09 Introductions, Escapes, Ferals and Hybrids 248 Earliest and Latest Dates of Summer Migrants 253 Latest and Earliest Dates of Winter Migrants 254 Non-accepted and non-submitted records 255 Contributors 256 Ringing Report 258 Hunstanton Cliffs: a Forgotten Migration Hotspot 268 1 Yellow-legged Gulls in Norfolk: 1 96 -200 1 273 Marmora’s Warbler on Scolt Head - a first for Norfolk 28 Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler at Blakeney Point - the second for Norfolk 283 Blyth’s Pipit at Happisburgh in September 1 999 - the second for Norfolk 285 Norfolk Mammal Report - 2001 Editor: Ian Keymer Editorial 287 Bats at Paston Great Barn 288 Memories of an ex-editor 298 Harvest Mice: more common than suspected? 299 Are we under-recording the Norfolk mink population? 301 National Key Sites for Water Voles in Norfolk 304 A Guide to identification of Shrews and Rodents 309 Published by NORFOLK AND NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Castle Museum, Norwich, NRl 3JU (Transactions Volume 35 part 2 October 2002) Please note that the page numbering in this report follows on from part 1 of the Transactions pub- lished in July 2002 ISSN 0375 7226 www.nnns.org.uk Keepsake back numbers are available from David & Iris Pauli, 8 Lindford Drive, Eaton, Norwich NR4 6LT Front cover photograph: Tree Sparrow (Richard Brooks) Back cover photograph: Grey Seal (Graeme Cresswell) NORFOLK BIRD REPORT - 2001 Editorial x On behalf of the Society 1 am pleased to present the annual report on the Birds of Norfolk. -

The Eastern Counties, — ——

^^^^^ gh Guides : ——- h^ ==h* - c\J : :ct> r ^c\i ==^JQO - T— ""> h»- [~^co '-_ 7 —^^— :n UOUNTIES /t\u* ton ^¥/ua( vY "IP Grantham ' TaUdngh oihv Mort.ml l y'iii.oco..^i>s ^u , ! v , ^i,,:;;^ , i / v '"'''.v/,,. ;r~ nsiimV *\ ?. ' kXOton /lEICESTERY Monftw /{, r fontf* k ^> h'i .;-"" A0% .-O Krlmarsh\ Blisw.wfli.i2 'oad&J Eelmdon. "VTolvei J''u/<}, upthill r9tc Ami? LoAviibo- 'Widfc *Baldock effbhurn f J Marti}*?' Ihxatingfard eitfktoii 7 " gifzzarcL t^r ' t>un.sti ^OXFORD '/'> Ainershain. finest WytHtrnd^iL Bickuuuis>^ Watliagtnti >^Hi^TV^cHnb£ ^M Shxplake- jfe-wrffa^eR E A PI Nla ^ | J. Bartholomew", E3ix k 4t> fcs J«<00®»»®00 o ocoo iO>l>Ot>l>N0500 o o t-o •0000500^000 OOO o ft ,'rH0D»O0006Q0CMlO>LO H00«3 . o CD Ocp CO COO O O OOCOO ^•OOOOOOOOO o o o o Q 5 m taWOWOOOCO>OiO •io»oo>o CO rHrHrHrHi-HrHrHrHrH . rH rH rH rH ^•COOOOOOOOO _CO O O 3 ojlOrHOrHrHrHGOOO :* :'i>ho 3 rHrH<MrHrHt-lr-l<M<M . • rH rH <M O ft . ocococococoococo CO CO CO CO 3 • t» d- t~ i>- rH (MH^HHHIMiMN • <M <M rH <M •oooomooojohoiooo ^5 rH oJcO<NO<M^<MCOOOOOOCO<MO rHrHCQrHr-1 rHrHrH<MrH(MrHrH<M IrHOCOOOOOCOCOCO 00 O CO 'oo r3 :C5000^ocooooocooo o o Q 525 : oq : : : :§? : : : : : O a OQ r-4 : o • : : :^3 : : : : * a a o 3 O : : : : : : : : : : « : a ^ ft .ft .o • n • o3 • o •J25 o9 S • 0) cS . CO . :oq • :,3 : B :ra : flo -»j cS rQ 2 s.d tJD ? B fcr - 00 O ?+3 J* ^b-3 a p 5 3 8.5 g^ - » * +•+* * * H—H— -r-+-»-+-f-+* * +-+ * * -f--r- Tast. -

Norfolk Bird Report 195 6

//N/ u Kv ' THE NORFOLK'‘Vf'ji BIRD REPORT 1956 - \8 LUwlE 18 PART 6 THE NORFOLK BIRD REPORT 195 6 Compiled by Michael J. Seago Assisted by the Records Committee : A. H. Daukes, E. A. Ellis, Miss C. E. Gay and R. A. Richardson CONTENTS page Introduction 1 Notes on Breeding Birds of the Reserves Scolt Head Island 3 Blakeney Point 5 Cley Marsh 7 Ranworth 9 Hickling 10 Horsey 13 Scroby Sands 14 Cley Bird Observatory 15 Selected Ringing Recoveries 18 Collared Doves in Norfolk 21 Classified Notes 24 Light-Vessel Notes 55 List of Contributors Inside back cover Published by The Norfolk Naturalists Trust (Assembly House, Theatre Street, Norwich) AND The Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society Part ( Transactions , Volume 18, 6) Collared Dove ( Streptopelia decaocto), adult and youno, Norfolk, 1956 The Norfolk Bird Report • INTRODUCTION. The Council of the Norfolk Naturalists Trust, in co-operation with the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society, is pleased to present to members the annual report on the birds of Norfolk. Unusual numbers of wildfowl were reported during the cold spell in February, particularly Bewick’s swans, scaup, golden-eye, velvet scoters, red-breasted mergansers and smew. Many redwings died in the hard weather and fieldfares were reduced to pecking white-fronted frozen carrots in the fields. 1 he pink-footed and I his geese in the Breydon area again showed a decline in numbers. annual decrease has taken place during the last ten years and less than 200 were seen in the i95^—57 "inter compared with 3,000 in adult lesser 1946. -

Transactions 1921

TRANSACTIONS OF THE Bov full! anti Bovumlj NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Presented to Members for 1921—22 VOL. XI.—Part iii Edited by the Honorary Secretary NORWICH Printed by A. E. Soman & Co. Prick 10- Borfulk anb Burundi Batnitalisfu’ Suddij 38G OFFICERS FOR 1922-23 President RUSSELL J. COLMAN Ex-President MISS E. L. TURNER, F.L.S., F.Z.S., Hon.M.B.O.U Vice-Presidents HER GRACE THE DUCHESS OF BEDFORD, F.Z.S., F.L.S., Hon.M.B.O.U. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF LEICESTER, G.C.V.O., C.M.G. MICHAEL BEVERLEY, M.D. SIR EUSTACE GURNEY, M.A., F.Z.S F.R.S. F.Z.S. F.L.S. SIR SIDNEY F. HARMER, K.B.E., J. H. GURNEY, , OLIVER, D.Sc., F.R.S. F. W. HARMER, M.A., F.G.S. PROF. F. W. Hon. Treasurer ROBERT GURNEY, M.A., F.L.S. Ingham Old Hall, Norfolk Hon. Secretary SYDNEY H. LONG, M.D., F.Z.S. 31, Surrey Street, Norwich Hon. Librarian F. C. HINDE Committee D. PAYLER W. H. M. ANDREWS MISS A. M. GELDART H. C. DAVIES M. TAYLOR J. A. CHRISTIE HALLS H. J. HOWARD H. J. THOULESS H. H. Wild Birds’ Protection Committee W. G. CLARKE J. H. GURNEY B. B. RIVIERE Q. E. GURNEY ROBERT GURNEY S. H. LONG Hon. Auditor VV. A. NICHOLSON — T R A N S A C T 1 0 N S OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY The1. Committee beg to direct the attention of authors of communications to the Society to the following Regulations 2. -

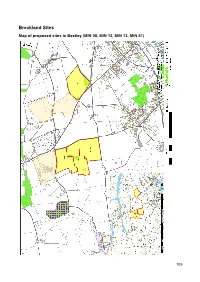

Proposed Mineral Extraction Sites

Proposed Mineral Extraction Sites 104 Breckland Sites Map of proposed sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51) MIN 12 - land north of Chapel Lane, Beetley Site Characteristics • The 16.38 hectare site is within the parish of Beetley • The estimated sand and gravel resource at the site is 1,175,000 tonnes • The proposer of the site has given a potential start date of 2025 and estimated the extraction rate to be 80,000 tonnes per annum. Based on this information the full mineral resource at the site could be extracted within 15 years, therefore approximately 960,000 tonnes could be extracted within the plan period. • The site is proposed by Middleton Aggregates Ltd as an extension to an existing site. • The site is currently in agricultural use and the Agricultural Land Classification scheme classifies the land as being Grade 3. • The site is 3.7km from Dereham and 12km from Fakenham, which are the nearest towns. • A reduced extraction area has been proposed of 14.9 hectares, which creates standoff areas to the south west of the site nearest to the buildings on Chapel Lane, and to the north west of the site nearest the dwellings on Church Lane. Amenity: The nearest residential property is 11m from the site boundary. There are 21 sensitive receptors within 250m of the site boundary. The settlement of Beetley is 260m away and Old Beetley is 380m away. However, land at the north-west and south-west corners is not proposed to be extracted. Therefore the nearest residential property is 96m from the extraction area and there are 18 sensitive receptors within 250m of the proposed extraction area. -

Breckland Sites Map of Proposed Sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51)

Breckland Sites Map of proposed sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51) 105 MIN 12 - land north of Chapel Lane, Beetley Site Characteristics • The 16.38 hectare site is within the parish of Beetley • The estimated sand and gravel resource at the site is 1,175,000 tonnes • The proposer of the site has given a potential start date of 2025 and estimated the extraction rate to be 80,000 tonnes per annum. Based on this information the full mineral resource at the site could be extracted within 15 years, therefore approximately 960,000 tonnes could be extracted within the plan period. • The site is proposed by Middleton Aggregates Ltd as an extension to an existing site. • The site is currently in agricultural use and the Agricultural Land Classification scheme classifies the land as being Grade 3. • The site is 3.7km from Dereham and 12km from Fakenham, which are the nearest towns. A reduced extraction area has been proposed of 14.9 hectares, which creates standoff areas to the south west of the site nearest to the buildings on Chapel Lane, and to the north west of the site nearest the dwellings on Church Lane. M12.1 Amenity: The nearest residential property is 11m from the site boundary. There are 22 sensitive receptors within 250m of the site boundary and six of these are within 100m of the site boundary. The settlement of Beetley is 260m away and Old Beetley is 380m away. However, land at the north-west and south-west corners is not proposed to be extracted. -

Environment Agency Anglian Region Strategy for Groundwater

£A-Ari0liAn W-uVer R^'Source.a ^ o x i3 Environment Agency Anglian Region Strategy for Groundwater Investigations and Modelling: Yare and North Norfolk Areas Scoping Study 27 January 2000 Entec UK Limited E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay. Peterborough PE2 5ZR En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y Report for Environment Agency Environment Agency Kingfisher House Anglian Region Goldhay Way Orton Goldhay Peterborough Strategy for PE2OZR Groundwater Main Contributors Investigations and Stuart Sutton Modelling: Yare and Tim Lewis Ben Fretwell North Norfolk Areas Issued by Scoping Study Tim Lewis 27 January 2000 Entec UK Limited Approved by Stuart Sutton Entec UK Limited 160-162 Abbey Forcgatc Shrewsbury Shropshire SY26BZ England Tel: +44 (0) 1743 342000 Fax: +44 (0) 1743 342010 f:\data\data\projects\hm-250\0073 2( 15770)\docs\n085i 3 .doc Certificate No. FS 34171 In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this report is printed on recycled paper produced from 100V. post-consumer waste. Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Strategy for Groundwater Investigations and Modelling 1 1.2 Structure of Strategy Projects and Approach to Seeking Approval 2 1.3 Organisation of this Report 3 2. Description of the Yare & North Norfolk Groundwater Resource Investigation Area and Current Understanding of the Hydrogeological System 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Location 7 2.3 Geology 7 2.4 Hydrology and Drainage 8 2.5 Basic Conceptual Hydrogeological Understanding 9 2.6 Water Resources 11 2.7 Conservation Interest 13 3. -

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY Vol.34 Parti (July 2001) THE natural f«5T0RY MUSEUM' 16 OCT 2001 BXCHA«a^^-D Q€NCRAL Llbf^&wiV TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK AND NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY ISSN 0375 7226 Volume 34 Part 1 (July 2001) Editor P.W.Lambley Assist. Ed. Roy Baker OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY 2001-2002 President: Dr Dick Hamond Vice-Presidents: Dr R. Baker, P.R. Banham, Mrs M. A. Brewster, A.L. Bull. K.B. Clarke, E.T. Daniels, D.A. Dorling, K.C. Durrant, R.E. Evans, R.C. Haney, R. Jones. Chairman: D.L. Paul. 8, Lindford Drive, Eaton, Norwich NR4 6LT. Tel: 01603 457270 Secretary: Dr A.R. Leech. 3, Eccles Rd, Holt. NR25 6HJ Assistant Secretary: J.F. Butcher. 4. Hillvue Close. New Costessey, NR5 ONQ Treasurer: D.l. Richmond, 42. Richmond Rise, Reepham. NRIO 4LS Membership Committee: D.L. Pauli (Chairman), (address above); S.M. Livermore, (Secretary) 70 Naseby Way, Dussingdale, Norwich NR7 OTP. Tel 01603 431849 Programme Committee: R.W. Ellis (Chairman). Dr S.R. Martin (Secretary) Publications Committee: Dr R. Baker (Chairman), P.W. Lambley, Dr M. Perrow. G.E. Dunmore, (Editors) Research Committee: R. W. Maidstone (Chairman), Dr l.F. Keymer (Secretary) Hon. Auditor: Mrs S. Pearson Wildlife 2000 Committee: S.M. Livermore, Project Director Elected Members of Council: Mrs C.M. Haines, Mrs A. Harrap, D.B. MacFarlane, M.H. Poulton, J. Clifton, F.LJ.L. Farrow, W.G. Mitchell, P. Westley, Dr R. Carpenter, A. Dixon, C.W. Penny . WILDLIFE 2000 During its 125th anniversary celebrations, the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society announced its intention to document the wildlife of Norfolk for the start of the new millennium in a project called Wildlife 2000. -

Mammal Report

) THE NORFOLK BIRD AND MAMMAL REPORT I960 (Transactions of The Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society, Volume 19 Part 5 : NORFOLK BIRD REPORT 1960 Edited by Michael J. Seago Records Committee R. A. Richardson, E. A. Ellis and The Editor CONTENTS page Introduction . 207 Notes on Breeding Birds of the Reserves Scolt Head Island . 216 Blakeney Point . 217 Cley and Salthouse . 218 Hickling Broad . 219 Horsey Mere . 220 Scroby Sands . 221 Cley Bird Observatory • , . 221 Selected Ringing Recoveries . 224 Classified Notes . 227 Light-Vessel Notes . 248 List of Contributors . 249 NORFOLK MAMMAL REPORT - 1960 Edited by F. J. Taylor Page Assisted by R. P. Bagnall-Oakeley and E. A. Ellis CONTENTS page Introduction . 250 Classified Notes . 252 List of Contributors . 265 Published by The Norfolk Naturalists Trust (Assembly House, Theatre Street, Norwich, Nor 62E) and The Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society (Castle Museum, Norwich) Norfolk Bird Report 1960 INTRODUCTION The Council of the Norfolk Naturalists Trust, in co-operation with the Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society, is pleased to present to members the annual report on the birds of Norfolk. Winter January-February : As in the previous year, the only cold spell occurred in mid- January and was of too short a duration to bring any unusual visitors. In the Breydon area were up to 400 white- fronted geese, with 80 bean-geese in the Yare valley. Among the latter was a single lesser white-front—the fifth fully authenticated county record. At Cawston, a ferruginous duck arrived Feb. 17th, remaining until early May. On the Nortli coast, brent geese peaked at 1,500 birds. -

Environment Agency Rip House, Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol, BS32 4UD

En v ir o n m e n t Agency ANNEX TO 'ACHIEVING THE QUALITY ’ Programme of Environmental Obligations Agreed by the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions and for Wales for Individual Water Companies As financed by the Periodic Review of Water Company Price Limits 2000*2005 The Environment Agency Rip House, Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol, BS32 4UD June 2000 ENVl RO N ME NT, AGEN CY 1 ]2 7 0 0 CONTENTS For each water and sewerage company' there are separate lists for continuous, intermittent discharges and water abstraction sites. 1. Anglian Water 2. Welsh Water 3. Northumbrian Water Group Pic 4. North West Water Pic 5. Severn Trent Pic 6. Southern Water Pic 7. South West Water Pic 8. Thames Water Pic 9. Wessex Water Pic 10. Yorkshire Water Pic 11. List of water abstraction sites for water supply only companies National Environment Programme Key E A R e g io n Water Company ID Effluent Type A A n g lia n . A Anglian Water SCE Sewage Crude Effluent M Midlands DC Dwr Cymru Welsh Water SSO Sewage Storm Overflows NE North East N Northumbrian Water STE Sewage Treated Effluent NW North W est NW North West Water CSO Combined Sewer Overflow S Southern ST Severn Trent Water EO Emergency Overflow SW South W est S Southern Water ST Storm Ta n k T Th a m e s sw South West Water . WA W ales T Thames Water Receiving Water Type wx Wessex Water C Coastal Y Yorkshire Water E Estuary G Groundwater D rive rs 1 Inland CM 3 CM 1 Urban Waste Water Treament Directive FF1 - 8 Freshwater Fisheries Directive Consent conditions/proposed requirements **!**!** GW Groundwater Directive Suspended solids/BOD/Ammonia SW 1 -12 Shellfish Water Directive NR Nutrient Removal S W A D 1 - 7 Surface Water Abstraction Directive P Phosphorus (mg/l) H A B 1 - 6 Habitats Directive N Nitrate (mg/i) B A T H 1 -1 3 Bathing Water Directive 2 y Secondary Treatment SSSI SSSI 3 y Tertiary Treatment QO(a) - QO(g) River and Estuarine Quality Objectives LOC Local priority schemes . -

RSPB REEDBED Plan Co-Ordinator: RSPB Plan Leader: Date: Stage: 31 December 1998 Final Draft June 2004 Revised Draft (Under Review) August 2005 Final Revised Draft

NORFOLK BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN Ref 1/H1 Tranche 1 Habitat Action Plan 1 Plan Author: RSPB REEDBED Plan Co-ordinator: RSPB Plan Leader: Date: Stage: 31 December 1998 Final draft June 2004 Revised draft (under review) August 2005 Final revised draft 1. CURRENT STATUS Definition • Reedbed is defined in this plan as S4 NVC communities; all other communities containing reed to be included in the fen action plan. • In Broadland, the fen resource has been surveyed and mapped. The distribution of reedbed vegetation by valley is as follows: S4 S4 transitions S26 Ant Valley 43.76ha 8.7ha 4.75ha Thurne Valley 112.95ha 25.92ha 3.13ha Muckfleet Valley 10.49ha 0.06ha 4.07ha Bure Valley 27.68ha 5.9ha 64.39ha Yare Valley 43.64ha - 279.07ha Waveney Valley 6.46ha 0.92ha 63.75ha • A rare habitat. The RSPB Reedbed Inventory suggests over 1,540 ha in Norfolk - almost 30% of the UK resource. However, the definition of reedbed used for this inventory was wider than that proposed here. Tables 1 and 2 below show the sites over 20 and 10 ha respectively from the inventory excluding known fen sites. • Reedbeds of less than 10 hectares are listed in Table 3 below. Some of these sites are known to support priority species, including bittern. • Over 50 species of conservation concern in Norfolk depend fully or partly on reedbeds and associated fens. However further research is necessary to fully identify the status of many species. The following are likely to provide the main focus: • birds - bittern, bearded tit, marsh harrier, Savi’s warbler; • mammals - otter, water shrew, harvest mouse; • moths - small dotted footman, Fenn’s wainscot, reed leopard; • other invertebrates - including BAP species such as the diving beetle (Bidessus unistriatus). -

Bird Report 1999 Norfolk Bird Report - 1999

Bird Report 1999 Norfolk Bird Report - 1999 Editor: Giles Dunmore Editorial 1 1 7 Review of the Year 120 Wetland Bird Surveys 127 Systematic List 130 Introductions, Escapes, Ferals and Hybrids 262 Earliest and Latest Dates of Summer Migrants 267 Latest and Earliest Dates of Winter Migrants 268 Non-accepted and non-submitted records 269 Contributors 270 Ringing Report 272 An unprecedented movement of Swallows and House Martins 282 The 1999 Nightingale Survey 286 Pied-billed Grebe in south-west Norfolk - the second county record 290 Black-winged Pratincole at Cley - third for Norfolk 292 American Golden Plover in south Norfolk - the second county record 294 An invasion of Pallid Swifts in Norfolk 295 Red-flanked Bluetail at Brancaster Staithe - second for Norfolk 297 Raptor Migration in north-east Norfolk 299 This year for the first time in many decades the Mammal Report has not been included in the current issue. The reason is that Dr Martin Perrow is editing a comprehensive book on the mammals of Norfolk as part of the Wildlife 2000 Project which aims to record the county’s fauna and flora at the turn of the century. The work involved has meant that the annual report on the mammals of Norfolk has had to be omitted for this year. We plan to return to the normal format next year so please send in your records of mammals to Dr Perrow at the School of Biological Sciences, UEA, Norwich NR4 7TJ. Dr Perrow also welcomes articles/papers on our county mammals for future inclusion. Details of the book and publication date will be announced in due course.