Transactions 1925

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

20 NOV 2Q02 I FXCHA^O'-"> 1 Norfolk Bird Report - 2001 Editor: Giles Dunmore Editorial 95 Review of the Year 98 Wetland Bird Surveys for Breydon and The Wash 1 05 Norfolk Bird Atlas 1 07 Systematic List 1 09 Introductions, Escapes, Ferals and Hybrids 248 Earliest and Latest Dates of Summer Migrants 253 Latest and Earliest Dates of Winter Migrants 254 Non-accepted and non-submitted records 255 Contributors 256 Ringing Report 258 Hunstanton Cliffs: a Forgotten Migration Hotspot 268 1 Yellow-legged Gulls in Norfolk: 1 96 -200 1 273 Marmora’s Warbler on Scolt Head - a first for Norfolk 28 Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler at Blakeney Point - the second for Norfolk 283 Blyth’s Pipit at Happisburgh in September 1 999 - the second for Norfolk 285 Norfolk Mammal Report - 2001 Editor: Ian Keymer Editorial 287 Bats at Paston Great Barn 288 Memories of an ex-editor 298 Harvest Mice: more common than suspected? 299 Are we under-recording the Norfolk mink population? 301 National Key Sites for Water Voles in Norfolk 304 A Guide to identification of Shrews and Rodents 309 Published by NORFOLK AND NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Castle Museum, Norwich, NRl 3JU (Transactions Volume 35 part 2 October 2002) Please note that the page numbering in this report follows on from part 1 of the Transactions pub- lished in July 2002 ISSN 0375 7226 www.nnns.org.uk Keepsake back numbers are available from David & Iris Pauli, 8 Lindford Drive, Eaton, Norwich NR4 6LT Front cover photograph: Tree Sparrow (Richard Brooks) Back cover photograph: Grey Seal (Graeme Cresswell) NORFOLK BIRD REPORT - 2001 Editorial x On behalf of the Society 1 am pleased to present the annual report on the Birds of Norfolk. -

The Eastern Counties, — ——

^^^^^ gh Guides : ——- h^ ==h* - c\J : :ct> r ^c\i ==^JQO - T— ""> h»- [~^co '-_ 7 —^^— :n UOUNTIES /t\u* ton ^¥/ua( vY "IP Grantham ' TaUdngh oihv Mort.ml l y'iii.oco..^i>s ^u , ! v , ^i,,:;;^ , i / v '"'''.v/,,. ;r~ nsiimV *\ ?. ' kXOton /lEICESTERY Monftw /{, r fontf* k ^> h'i .;-"" A0% .-O Krlmarsh\ Blisw.wfli.i2 'oad&J Eelmdon. "VTolvei J''u/<}, upthill r9tc Ami? LoAviibo- 'Widfc *Baldock effbhurn f J Marti}*?' Ihxatingfard eitfktoii 7 " gifzzarcL t^r ' t>un.sti ^OXFORD '/'> Ainershain. finest WytHtrnd^iL Bickuuuis>^ Watliagtnti >^Hi^TV^cHnb£ ^M Shxplake- jfe-wrffa^eR E A PI Nla ^ | J. Bartholomew", E3ix k 4t> fcs J«<00®»»®00 o ocoo iO>l>Ot>l>N0500 o o t-o •0000500^000 OOO o ft ,'rH0D»O0006Q0CMlO>LO H00«3 . o CD Ocp CO COO O O OOCOO ^•OOOOOOOOO o o o o Q 5 m taWOWOOOCO>OiO •io»oo>o CO rHrHrHrHi-HrHrHrHrH . rH rH rH rH ^•COOOOOOOOO _CO O O 3 ojlOrHOrHrHrHGOOO :* :'i>ho 3 rHrH<MrHrHt-lr-l<M<M . • rH rH <M O ft . ocococococoococo CO CO CO CO 3 • t» d- t~ i>- rH (MH^HHHIMiMN • <M <M rH <M •oooomooojohoiooo ^5 rH oJcO<NO<M^<MCOOOOOOCO<MO rHrHCQrHr-1 rHrHrH<MrH(MrHrH<M IrHOCOOOOOCOCOCO 00 O CO 'oo r3 :C5000^ocooooocooo o o Q 525 : oq : : : :§? : : : : : O a OQ r-4 : o • : : :^3 : : : : * a a o 3 O : : : : : : : : : : « : a ^ ft .ft .o • n • o3 • o •J25 o9 S • 0) cS . CO . :oq • :,3 : B :ra : flo -»j cS rQ 2 s.d tJD ? B fcr - 00 O ?+3 J* ^b-3 a p 5 3 8.5 g^ - » * +•+* * * H—H— -r-+-»-+-f-+* * +-+ * * -f--r- Tast. -

Norfolk Bird Report 195 6

//N/ u Kv ' THE NORFOLK'‘Vf'ji BIRD REPORT 1956 - \8 LUwlE 18 PART 6 THE NORFOLK BIRD REPORT 195 6 Compiled by Michael J. Seago Assisted by the Records Committee : A. H. Daukes, E. A. Ellis, Miss C. E. Gay and R. A. Richardson CONTENTS page Introduction 1 Notes on Breeding Birds of the Reserves Scolt Head Island 3 Blakeney Point 5 Cley Marsh 7 Ranworth 9 Hickling 10 Horsey 13 Scroby Sands 14 Cley Bird Observatory 15 Selected Ringing Recoveries 18 Collared Doves in Norfolk 21 Classified Notes 24 Light-Vessel Notes 55 List of Contributors Inside back cover Published by The Norfolk Naturalists Trust (Assembly House, Theatre Street, Norwich) AND The Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society Part ( Transactions , Volume 18, 6) Collared Dove ( Streptopelia decaocto), adult and youno, Norfolk, 1956 The Norfolk Bird Report • INTRODUCTION. The Council of the Norfolk Naturalists Trust, in co-operation with the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society, is pleased to present to members the annual report on the birds of Norfolk. Unusual numbers of wildfowl were reported during the cold spell in February, particularly Bewick’s swans, scaup, golden-eye, velvet scoters, red-breasted mergansers and smew. Many redwings died in the hard weather and fieldfares were reduced to pecking white-fronted frozen carrots in the fields. 1 he pink-footed and I his geese in the Breydon area again showed a decline in numbers. annual decrease has taken place during the last ten years and less than 200 were seen in the i95^—57 "inter compared with 3,000 in adult lesser 1946. -

English Nature Research Report

Yatural Area: 23. Lincolnshire Marsh and Geological Significance: Notable Coast (provisional) General geological character: The solid geology of the Lincolnshire Marsh and Coast Natural Area is bminated by Cretaceous chalk (approximately 97-83 Ma) although the later Quaternary deposits (the last 2 Ma) give thc area its overall. charactcr. 'The chalk is only well exposed on thc south bank of the Humber, where quarries and cuttings providc exposures of the Upper Cretaceous Chalk. 'me chalk is a very pure limestone deposited on the floor of a tropical sea. During Quaternary timcs, the area was glaciated on several occasions and as a result the area is covered by a variety of glacial deposits, representing an unknown number of glacial ('lcc Age') and interglacial phases. rhe glacial deposits consist mainly of sands, gravels and clays in variable thicknesses. These are derived primarily from the erosion of surrounding bedrock and therefore tend to have similar lithological characteristics, usually with a high chalk content. The glacial deposits are particularly important because of the controversy surrounding their correlation with the timing and sequence in other parts of England, especially East Anglia. The Quaternary deposits are well exposed in coastal cliffs of the area. Key geological features: Coastal cliffs consisting of glacial sands, gravels and clays Exposures of Cretaceous chalk Number of GCR sites: Oxfordian: 1 Kimmeridgian: I Aptian-Rlbian: i Quaternary of Eastern England: 1 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~ ~ ~ ~~ GeologicaVgeomorphological SSSI coverage: 'here are 2 (P)SSSIs in the Natural Area covering 4 GCR SlLs which represent 4 different GCR networks. The site coverage includes South Ferriby Chalk Pit SSSI which contains an important Upper Jurassic succession, overlain by Cretaceous deposits. -

Transactions 1921

TRANSACTIONS OF THE Bov full! anti Bovumlj NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Presented to Members for 1921—22 VOL. XI.—Part iii Edited by the Honorary Secretary NORWICH Printed by A. E. Soman & Co. Prick 10- Borfulk anb Burundi Batnitalisfu’ Suddij 38G OFFICERS FOR 1922-23 President RUSSELL J. COLMAN Ex-President MISS E. L. TURNER, F.L.S., F.Z.S., Hon.M.B.O.U Vice-Presidents HER GRACE THE DUCHESS OF BEDFORD, F.Z.S., F.L.S., Hon.M.B.O.U. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF LEICESTER, G.C.V.O., C.M.G. MICHAEL BEVERLEY, M.D. SIR EUSTACE GURNEY, M.A., F.Z.S F.R.S. F.Z.S. F.L.S. SIR SIDNEY F. HARMER, K.B.E., J. H. GURNEY, , OLIVER, D.Sc., F.R.S. F. W. HARMER, M.A., F.G.S. PROF. F. W. Hon. Treasurer ROBERT GURNEY, M.A., F.L.S. Ingham Old Hall, Norfolk Hon. Secretary SYDNEY H. LONG, M.D., F.Z.S. 31, Surrey Street, Norwich Hon. Librarian F. C. HINDE Committee D. PAYLER W. H. M. ANDREWS MISS A. M. GELDART H. C. DAVIES M. TAYLOR J. A. CHRISTIE HALLS H. J. HOWARD H. J. THOULESS H. H. Wild Birds’ Protection Committee W. G. CLARKE J. H. GURNEY B. B. RIVIERE Q. E. GURNEY ROBERT GURNEY S. H. LONG Hon. Auditor VV. A. NICHOLSON — T R A N S A C T 1 0 N S OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY The1. Committee beg to direct the attention of authors of communications to the Society to the following Regulations 2. -

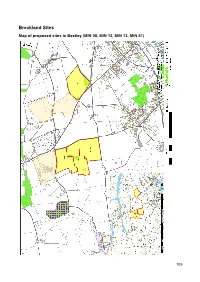

Proposed Mineral Extraction Sites

Proposed Mineral Extraction Sites 104 Breckland Sites Map of proposed sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51) MIN 12 - land north of Chapel Lane, Beetley Site Characteristics • The 16.38 hectare site is within the parish of Beetley • The estimated sand and gravel resource at the site is 1,175,000 tonnes • The proposer of the site has given a potential start date of 2025 and estimated the extraction rate to be 80,000 tonnes per annum. Based on this information the full mineral resource at the site could be extracted within 15 years, therefore approximately 960,000 tonnes could be extracted within the plan period. • The site is proposed by Middleton Aggregates Ltd as an extension to an existing site. • The site is currently in agricultural use and the Agricultural Land Classification scheme classifies the land as being Grade 3. • The site is 3.7km from Dereham and 12km from Fakenham, which are the nearest towns. • A reduced extraction area has been proposed of 14.9 hectares, which creates standoff areas to the south west of the site nearest to the buildings on Chapel Lane, and to the north west of the site nearest the dwellings on Church Lane. Amenity: The nearest residential property is 11m from the site boundary. There are 21 sensitive receptors within 250m of the site boundary. The settlement of Beetley is 260m away and Old Beetley is 380m away. However, land at the north-west and south-west corners is not proposed to be extracted. Therefore the nearest residential property is 96m from the extraction area and there are 18 sensitive receptors within 250m of the proposed extraction area. -

Breckland Sites Map of Proposed Sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51)

Breckland Sites Map of proposed sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51) 105 MIN 12 - land north of Chapel Lane, Beetley Site Characteristics • The 16.38 hectare site is within the parish of Beetley • The estimated sand and gravel resource at the site is 1,175,000 tonnes • The proposer of the site has given a potential start date of 2025 and estimated the extraction rate to be 80,000 tonnes per annum. Based on this information the full mineral resource at the site could be extracted within 15 years, therefore approximately 960,000 tonnes could be extracted within the plan period. • The site is proposed by Middleton Aggregates Ltd as an extension to an existing site. • The site is currently in agricultural use and the Agricultural Land Classification scheme classifies the land as being Grade 3. • The site is 3.7km from Dereham and 12km from Fakenham, which are the nearest towns. A reduced extraction area has been proposed of 14.9 hectares, which creates standoff areas to the south west of the site nearest to the buildings on Chapel Lane, and to the north west of the site nearest the dwellings on Church Lane. M12.1 Amenity: The nearest residential property is 11m from the site boundary. There are 22 sensitive receptors within 250m of the site boundary and six of these are within 100m of the site boundary. The settlement of Beetley is 260m away and Old Beetley is 380m away. However, land at the north-west and south-west corners is not proposed to be extracted. -

Wherryman's Way Circular Walks

Brundall Wherryman’s Way Circular Walks Surlingham Postwick Ferry House To Coldham Hall Tavern Bird Hide Surlingham Church Marsh R.S.P.B. Nature Reserve St Saviours Church (ruin) Surlingham To Whitlingham River Yare Surlingham Parish Church To Ted Ellis Trust at Wheatfen Nature Reserve Bramerton To Rockland St Mary 2 miles To Norwich 4 miles Norfolk County Council Contents Introduction page 2 Wherries and wherryman page 3 Circular walks page 4 Walk 1 Whitlingham page 6 Walk 2 Bramerton page 10 Walk 3 Surlingham page 14 Walk 4 Rockland St Mary page 18 Walk 5 Claxton page 22 Walk 6 Langley with Hardley page 26 Wherryman’s Way map page 30 Walk 7 Chedgrave page 32 Walk 8 Loddon page 36 Walk 9 Loddon Ingloss page 40 If you would like this document in large print, audio, Braille, Walk 10 Loddon – Warren Hills page 44 alternative format or in a Walk 11 Reedham page 48 different language please contact Paul Ryan on 01603 Walk 12 Berney Arms page 52 223317, minicom 01603 223833 or [email protected] Project information page 56 1 Introduction Wherries and wherrymen Wherryman’s Way Wherries have been part of life in the Broads for hundreds of years. The Wherryman’s Way is in the Broads, which is Britain’s largest protected Before roads and railways, waterways were the main transport routes wetland. The route passes through many nature reserves and Sites of for trade and people. River trade – the ability to bring in raw materials Special Scientific Interest, a reflection of the rich wildlife diversity of the and export finished goods – helped make Norwich England’s second city, Yare Valley. -

Environment Agency Anglian Region Strategy for Groundwater

£A-Ari0liAn W-uVer R^'Source.a ^ o x i3 Environment Agency Anglian Region Strategy for Groundwater Investigations and Modelling: Yare and North Norfolk Areas Scoping Study 27 January 2000 Entec UK Limited E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay. Peterborough PE2 5ZR En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y Report for Environment Agency Environment Agency Kingfisher House Anglian Region Goldhay Way Orton Goldhay Peterborough Strategy for PE2OZR Groundwater Main Contributors Investigations and Stuart Sutton Modelling: Yare and Tim Lewis Ben Fretwell North Norfolk Areas Issued by Scoping Study Tim Lewis 27 January 2000 Entec UK Limited Approved by Stuart Sutton Entec UK Limited 160-162 Abbey Forcgatc Shrewsbury Shropshire SY26BZ England Tel: +44 (0) 1743 342000 Fax: +44 (0) 1743 342010 f:\data\data\projects\hm-250\0073 2( 15770)\docs\n085i 3 .doc Certificate No. FS 34171 In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this report is printed on recycled paper produced from 100V. post-consumer waste. Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Strategy for Groundwater Investigations and Modelling 1 1.2 Structure of Strategy Projects and Approach to Seeking Approval 2 1.3 Organisation of this Report 3 2. Description of the Yare & North Norfolk Groundwater Resource Investigation Area and Current Understanding of the Hydrogeological System 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Location 7 2.3 Geology 7 2.4 Hydrology and Drainage 8 2.5 Basic Conceptual Hydrogeological Understanding 9 2.6 Water Resources 11 2.7 Conservation Interest 13 3. -

Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY Vol.34 Parti (July 2001) THE natural f«5T0RY MUSEUM' 16 OCT 2001 BXCHA«a^^-D Q€NCRAL Llbf^&wiV TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK AND NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY ISSN 0375 7226 Volume 34 Part 1 (July 2001) Editor P.W.Lambley Assist. Ed. Roy Baker OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY 2001-2002 President: Dr Dick Hamond Vice-Presidents: Dr R. Baker, P.R. Banham, Mrs M. A. Brewster, A.L. Bull. K.B. Clarke, E.T. Daniels, D.A. Dorling, K.C. Durrant, R.E. Evans, R.C. Haney, R. Jones. Chairman: D.L. Paul. 8, Lindford Drive, Eaton, Norwich NR4 6LT. Tel: 01603 457270 Secretary: Dr A.R. Leech. 3, Eccles Rd, Holt. NR25 6HJ Assistant Secretary: J.F. Butcher. 4. Hillvue Close. New Costessey, NR5 ONQ Treasurer: D.l. Richmond, 42. Richmond Rise, Reepham. NRIO 4LS Membership Committee: D.L. Pauli (Chairman), (address above); S.M. Livermore, (Secretary) 70 Naseby Way, Dussingdale, Norwich NR7 OTP. Tel 01603 431849 Programme Committee: R.W. Ellis (Chairman). Dr S.R. Martin (Secretary) Publications Committee: Dr R. Baker (Chairman), P.W. Lambley, Dr M. Perrow. G.E. Dunmore, (Editors) Research Committee: R. W. Maidstone (Chairman), Dr l.F. Keymer (Secretary) Hon. Auditor: Mrs S. Pearson Wildlife 2000 Committee: S.M. Livermore, Project Director Elected Members of Council: Mrs C.M. Haines, Mrs A. Harrap, D.B. MacFarlane, M.H. Poulton, J. Clifton, F.LJ.L. Farrow, W.G. Mitchell, P. Westley, Dr R. Carpenter, A. Dixon, C.W. Penny . WILDLIFE 2000 During its 125th anniversary celebrations, the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society announced its intention to document the wildlife of Norfolk for the start of the new millennium in a project called Wildlife 2000. -

GREATER NORWICH DEVELOPMENT PARTNERSHIP TECHNICAL CONSULTATION FULL REPORT (Final Draft)

GREATER NORWICH DEVELOPMENT PARTNERSHIP TECHNICAL CONSULTATION FULL REPORT (Final draft) Prepared for Greater Norwich Development Partnership Thorpe Lodge, Yarmouth Road Thorpe St Andrew Norwich NR7 0DU Prepared by: Michael Mackman BA (Hons), MMRS, FCIM, Chartered Marketer 14 November 2008 Greater Norwich Development Partnership – Joint Core Strategy Consultation P08872 14 November 2008 Page 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Obviously, the evaluation of the comments on the GNDP Regulation 25 consultation is a matter for the Partnership. However, it may be helpful to draw out some common and recurring themes. There are many expressions of concern about the effects of further development on key local infrastructure. These include (but are not exclusively) water and sewerage, health services, transportation/ roads, community facilities and infrastructure, education, policing and the environment (including impacts on SSSIs, nature reserves and green spaces). Many respondents express views to the effect that local resources are at capacity or above, and that further development must bring with it benefits to support new populations, wherever housed. There are particular concerns in some rural communities, although some also welcome controlled development as a means of assuring or enhancing local services, and request a higher development “status” or the development of specific sites. Others are concerned about “knock on” effects on local infrastructure, including roads, local schools and so on. This is coupled with concerns about sustainability, the desirability of “green infrastructure” and about ensuring that new development has the minimum carbon footprint. There are also suggestions about measures to improve the carbon footprint of existing developments, for example, through renewables technology. Unsurprisingly, these concerns are balanced by suggestions from agents, landowners, developers and businesses suggesting the desirability of additional development, or the development of specific sites. -

Mammal Report

) THE NORFOLK BIRD AND MAMMAL REPORT I960 (Transactions of The Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society, Volume 19 Part 5 : NORFOLK BIRD REPORT 1960 Edited by Michael J. Seago Records Committee R. A. Richardson, E. A. Ellis and The Editor CONTENTS page Introduction . 207 Notes on Breeding Birds of the Reserves Scolt Head Island . 216 Blakeney Point . 217 Cley and Salthouse . 218 Hickling Broad . 219 Horsey Mere . 220 Scroby Sands . 221 Cley Bird Observatory • , . 221 Selected Ringing Recoveries . 224 Classified Notes . 227 Light-Vessel Notes . 248 List of Contributors . 249 NORFOLK MAMMAL REPORT - 1960 Edited by F. J. Taylor Page Assisted by R. P. Bagnall-Oakeley and E. A. Ellis CONTENTS page Introduction . 250 Classified Notes . 252 List of Contributors . 265 Published by The Norfolk Naturalists Trust (Assembly House, Theatre Street, Norwich, Nor 62E) and The Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society (Castle Museum, Norwich) Norfolk Bird Report 1960 INTRODUCTION The Council of the Norfolk Naturalists Trust, in co-operation with the Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society, is pleased to present to members the annual report on the birds of Norfolk. Winter January-February : As in the previous year, the only cold spell occurred in mid- January and was of too short a duration to bring any unusual visitors. In the Breydon area were up to 400 white- fronted geese, with 80 bean-geese in the Yare valley. Among the latter was a single lesser white-front—the fifth fully authenticated county record. At Cawston, a ferruginous duck arrived Feb. 17th, remaining until early May. On the Nortli coast, brent geese peaked at 1,500 birds.