Citizenship and Deviations from It in Ergo Proxy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watch Deadman Wonderland Online

1 / 2 Watch Deadman Wonderland Online Bloody Hell—this is what Deadman Wonderland literally is! ... List of Elfen Lied episodes Very rare Lucy/Nyu & Nana figures from Elfen Lied. ... Dream Tech Series Elfen Lied Lucy & Nyu figures with extra faces set. at the best online prices at …. Watch Deadman Wonderland online animestreams. Other name: デッドマン・ワンダーランド. Plot Summary: Ganta Igarashi has been convicted of a crime that .... AnimeHeaven - watch Deadman Wonderland OAD (Dub) - Deadman Wonderland OVA (Dub) Episode anime online free and more animes online in high quality .... Deadman wonderland episode 1 english dubbed. Deadman . Crunchyroll deadman wonderland full episodes streaming online for free.Dead man wonderland .... Watch Deadman Wonderland 2011 full Series free, download deadman wonderland 2011. Stars: Kana Hanazawa, Greg Ayres, Romi Pak.. BOOK ONLINE. Kids go free before 12 ... Pledge your love as your nearest and dearest watch, with the Canadian Rockies as your witness. Then, head inside for .... [ online ] Available http://csii.usc.edu/documents/Nationalisms of and against ... ' Deadman Wonderland .... Nov 2, 2020 — This show received positive comments from the viewers. However, does it mean there will be a second season? Gandi Baat 5 All Episodes Free ( watch online ) #gandi_baat #webseries tags ... Watch Deadman Wonderland Online English Dubbed full episodes for Free.. Best anime series you can watch in 2021 Apr 09, 2014 · 1st 2 Berserk Films Stream on Hulu for 1 Week. Berserk: The ... Deadman Wonderland (2011). Ganta is .... 2 hours ago — Just like Sword Art Online these 5 are ... 1 year ago. 1,252,109 views. Why DEADMAN WONDERLAND isn't getting a Season 2. -

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 in Partnership with the Japan Foundation

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 In partnership with the Japan Foundation Chapter - September 29th - October 1st, 2017 Aberystwyth Arts Centre – October 28th, 2017 The Largest Festival of Japanese Animation in Wales Announces Dates, Locations and Films for 2017 The Kotatsu Japanese Animation Festival returns to Wales for another edition in 2017 with audiences able to enjoy a whole host of Welsh premieres, a Japanese marketplace, and a Q&A and special film screening hosted by an important figure from the Japanese animation industry. The festival begins in Cardiff at Chapter Arts on the evening of Friday, September 29th with a screening of Masaaki Yuasa’s film The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (2017), a charming romantic romp featuring a love-sick student chasing a girl through the streets of Kyoto, encountering magic and weird situations as he does so. Festival head, Eiko Ishii Meredith will be on hand to host the opening ceremony and a party to celebrate the start of the festival which will last until October 01st and include a diverse array of films from near-future tales Napping Princess (2017) to the internationally famous mega-hit Your Name (2016). The Cardiff portion of the festival ends with a screening of another Yuasa film, the much-requested Mind Game (2004), a film definitely sure to please fans of surreal and adventurous animation. This is the perfect chance for people to see it on the big-screen since it is rarely screened. A selection of these films will then be screened at the Aberystywth Arts Centre on October 28th as Kotatsu helps to widen access to Japanese animated films to audiences in different locations. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

Protoculture Addicts

PA #89 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #89 ( Fall 2006 ) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 16 HELLSING OVA NEWS Interview with Kouta Hirano & Yasuyuki Ueda Character Rundown 8 Anime & Manga News By Zac Bertschy 89 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) 91 Related Products Releases 20 VOLTRON 93 Manga Releases Return Of The King: Voltron Comes to DVD Voltron’s Story Arcs: The Saga Of The Lion Force Character Profiles MANGA PREVIEW By Todd Matthy 42 Mushishi 24 MUSHISHI Overview ANIME WORLD Story & Cast By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 58 Train Ride A Look at the Various Versions of the Train Man ANIME STORIES 60 Full Metal Alchemist: Timeline 62 Gunpla Heaven 44 ERGO PROXY Interview with Katsumi Kawaguchi Overview 64 The Modern Japanese Music Database Character Profiles Sample filePart 36: Home Page 20: Hitomi Yaida By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Part 37: FAQ 22: The Same But Different 46 NANA 62 Anime Boston 2006 Overview Report, Anecdocts from Shujirou Hamakawa, Character Profiles Anecdocts from Sumi Shimamoto By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 70 Fantasia Genre Film Festival 2006 Report, Full Metal Alchemist The Movie, 50 PARADISE KISS Train Man, Great Yokai War, God’s Left Overview & Character Profiles Hand-Devil’s Right Hand, Ultraman Max By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 52 RESCUE WINGS REVIEWS Overview & Character Profiles 76 Live-Action By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Nana 78 Manga 55 SIMOUN 80 Related Products Overview & Character Profiles CD Soundtracks, Live-Action, Music Video By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. -

DIACRONIA Ensaios De Comunicação, Cultura E Ficção Científica

João Matias de Oliveira Neto Wander Shirukaya (orgs.) D IA CRO NIA Ensaios de comunicação, cultura e ficção científica João Pessoa 2015 DIACRONIA Ensaios de comunicação, cultura e ficção científica João Matias de Oliveira Neto Wander Shirukaya (organizadores) Revisão e editoração: Alex de Souza Imagem da capa: Detalhe de foto tirada pelo Hubble/NASA Série Veredas, 32 2015 978-85-67732-42-8 Capa - Expediente - Sumário - Autores Marca de Fantasia Rua Maria Elizabeth, 87/407 João Pessoa, PB. 58045-180 www.marcadefantasia.com [email protected] A editora Marca de Fantasia é uma atividade da Associação Marca de Fantasia e um projeto de extensão do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação da UFPB Diretor/ Editor: Henrique Magalhães Conselho Editorial: Adriano de León - UFPB Edgar Franco - UFG Marcos Nicolau - UFPB Nílton Milanez - UESB Paulo Ramos - UNIFESP Roberto Elísio dos Santos - USCS/SP Waldomiro Vergueiro - USP Wellington Pereira - UFPB Esta é uma obra exclusivamente de análise, que pretende contribuir para a discussão acadêmica. O uso das imagens é feito apenas para estudo, de acordo com o artigo 46 da Lei 9610. Todos os direitos das imagens pertencem a seus detentores. Capa - Expediente - Sumário - Autores Sumário Prefácio 6 Braulio Tavares A pessoa humana na ficção científica 15 Antonio Maranganha Arte e ciência na criação de mundos alternativos 62 Tiago Franklin Astrofotografia como ficção científica? 92 Jhésus Tribuzi Narrativas, suportes e experimentações: origem e expansão da ficção científica 114 Gabriel Lyra Ciência, pensamento e modernidade na ficção científica: Isaac Asimov e interpretações possíveis 160 João Matias de Oliveira Neto Paranoias e androides: a percepção da realidade em Blade Runner e Ergo Proxy 186 Wander Shirukaya Capa - Expediente - Sumário - Autores PREFÁCIO Braulio Tavares estudo e a análise da narrativa de ficção científica O (FC) foi nos EUA e na Europa uma atividade restrita a um pequeno número de escritores e críticos sem vínculo acadêmico durante várias décadas. -

Cv Fabián Sierra English

NAME: FABIÁN SIERRA JOB: FREELANCE SUBTITLER / TIME CODER / ENGLISH-SPANISH TRANSLATOR ADRESS: MOSTAR, 34, 4º-A, 08207 SABADELL (BARCELONA) SPAIN TEL.: 34 687684013 or 34 937460392 E-MAILS: [email protected] and [email protected] Education: -First course Translation & Interpretation (Castillian Spanish-English) UAB. -Filmmaking in Escuela Micro Obert (Barcelona). -Scriptwriting Master Class by Syd Field in Madrid (2005). Experience: -Sonilab Estudios: subtitler, English-Spanish translator and documentation manager from 2000 to 2003. -Origin Audiovisual Networks: subtitler, English-Spanish translator and documentation manager from 2003 to 2005. -Mizar Multimedia: Technical Scriptwriting Control April- June 2005. -Contexto Audiovisual (Subtitling company): Subtitler, English-Spanish translator and Production manager. From April 2006 'til November 2007. -Freelance Subtitler and English-Spanish translator from January 2008. Some works made: JONU MEDIA: Subtitling of “Love Hina” (Anime series), “Patlabor 2” y 3 (series and movies), “Niea Under 7” (series), “Fushigi Yugi” (series), “Kare Kano” (series), “Melty Lancer” (series), “Yu yu Hakusho” (series and movies), “Dual” (series), “Angel Sanctuary” (series), “Azul” (series), “Clamp Detectives” (series), “Comic Party” (series), “El último reino” (Movie), “Fruits Basket” (series), “Hand Maid May” (series), “I, my, me, Strawberry eggs” (series), “Quién es el 11º pasaJero” (movie), “Kimagure Orange Road” (series), “Tokio Vice” (movie), “La tumba de las luciérnagas” (movie), etc. SELECTA VISIÓN: Subtitling of “Patlabor” (Movie), “Orphen” (series & movies), “Samurai Champloo” (Series), “Érase una vez en China 2” (Movie), “Game of death” (Movie), “Ergo Proxy” (series) y “Rahxephon” (series), among others. SOGEMEDIA/SUEVIA FILMS: Subtitling of “Qué bello es vivir”, “El tercer hombre”, “Juan Nadie”, “Sangre sobre el sol”, “Hasta que las nubes pasen”, “Abraxas”, “La cosecha mortal”, “The horror store”, among many others. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 . See, for example, Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto’s review article “Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. By Susan J. Napier” in The Journal of Asian Studies , 61(2), 2002, pp. 727–729. 2 . Key texts relevant to these thinkers are as follows: Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I and Cinema II (London: Athlone Press, 1989); Jacques Ranciere, The Future of the Image (London and New York: Verso, 2007); Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement Affect, Sensation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002); Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London and New York: Verso, 1989); Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993). 3 . This is a recurrent theme in The Anime Machine – and although Lamarre has a carefully nuanced approach to the significance of technology, he ultimately favours an engagement with the specificity of the technology as the primary starting point for an analysis of the “animetic” image: see Lamarre, 2009: xxi–xxiii. 4 . For a concise summing up of this point and a discussion of the distinction between creation and “fabrication” see Collingwood, 1938: pp. 128–131. 5 . Lamarre is strident critic of such tendencies – see The Anime Machine , p. xxviii & p. 89. 6 . “Culturalism” is used here to denote approaches to artistic products and artefacts that prioritize indigenous traditions and practices as a means to explain the artistic rationale of the content. While it is a valuable exercise in contextualization, there are limits to how it can account for creative processes themselves. 7 . Shimokawa Ōten produced Imokawa Mukuzo Genkanban no Maki (The Tale of Imokawa Mukuzo the Concierge ) which was the first animated work to be shown publicly – the images were retouched on the celluloid. -

Politics and Mecha Sci-Fi in Anime Anime Reviews

July 27, 2011 Politics and Mecha Why you can’t have one without the other Sci-Fi in Anime Looking at the worlds of science fiction summer 2011 through a Japanese lens Anime Reviews Check out Ergo Proxy, Working!!, and more Mecha Edition MECHA EDITION TSUNAMI 1 Letter from the Editor Hey readers! Thanks for reading this In any case, I’d like to thank Ste- magazine. For those of you new to ven Chan and Gregory Ambros for Tsunami Staff this publication, this is Tsunami their contributions to this year’s is- fanzine. It’s a magazine created by sue, and Kristen McGuire for her EDITOR-IN-CHIEF current and former members of Ter- lovely artwork. I’d also like to thank Chris Yi rapin Anime Society, a student orga- Robby Blum and former editor Julia nization at the University of Mary- Salevan for their advice and help in DESIGN AND LAYOUT land, College Park. These anime, getting this issue produced. In addi- Chris Yi manga, and cosplay fans produce ar- tion, it was a pleasure working with ticles, news, reviews, editorials, fic- my fellow officers Ary, Robby, and COVERS tion, art, and other works of interest Lucy. Lastly, I want to thank past Kristen McGuire that are specifically aimed towards contributors and club members who you, our fellow fan, whether you’re made the production of past issues NEWS AND REVIEWS an avid otaku...or someone looking possible, and all the members that I Chris Yi for some time to kill. ...Hence the had the pleasure of getting to know word “fanzine.” and meet in my lone year as Editor- WRITERS Greg Ambros, Steven Chan, Chris Yi in-Chief, and in my two years as a This year, I decided to give Tsunami club member with Terrapin Anime a sort of “TIMES Magazine” look. -

Harga Sewaktu Wak Jadi Sebelum

HARGA SEWAKTU WAKTU BISA BERUBAH, HARGA TERBARU DAN STOCK JADI SEBELUM ORDER SILAHKAN HUBUNGI KONTAK UNTUK CEK HARGA YANG TERTERA SUDAH FULL ISI !!!! Berikut harga HDD per tgl 14 - 02 - 2016 : PROMO BERLAKU SELAMA PERSEDIAAN MASIH ADA!!! EXTERNAL NEW MODEL my passport ultra 1tb Rp 1,040,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 2tb Rp 1,560,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 3tb Rp 2,500,000 NEW wd element 500gb Rp 735,000 1tb Rp 990,000 2tb WD my book Premium Storage 2tb Rp 1,650,000 (external 3,5") 3tb Rp 2,070,000 pakai adaptor 4tb Rp 2,700,000 6tb Rp 4,200,000 WD ELEMENT DESKTOP (NEW MODEL) 2tb 3tb Rp 1,950,000 Seagate falcon desktop (pake adaptor) 2tb Rp 1,500,000 NEW MODEL!! 3tb Rp - 4tb Rp - Hitachi touro Desk PRO 4tb seagate falcon 500gb Rp 715,000 1tb Rp 980,000 2tb Rp 1,510,000 Seagate SLIM 500gb Rp 750,000 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb Rp 1,550,000 1tb seagate wireless up 2tb Hitachi touro 500gb Rp 740,000 1tb Rp 930,000 Hitachi touro S 7200rpm 500gb Rp 810,000 1tb Rp 1,050,000 Transcend 500gb Anti shock 25H3 1tb Rp 1,040,000 2tb Rp 1,725,000 ADATA HD 710 750gb antishock & Waterproof 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb INTERNAL WD Blue 500gb Rp 710,000 1tb Rp 840,000 green 2tb Rp 1,270,000 3tb Rp 1,715,000 4tb Rp 2,400,000 5tb Rp 2,960,000 6tb Rp 3,840,000 black 500gb Rp 1,025,000 1tb Rp 1,285,000 2tb Rp 2,055,000 3tb Rp 2,680,000 4tb Rp 3,460,000 SEAGATE Internal 500gb Rp 685,000 1tb Rp 835,000 2tb Rp 1,215,000 3tb Rp 1,655,000 4tb Rp 2,370,000 Hitachi internal 500gb 1tb Toshiba internal 500gb Rp 630,000 1tb 2tb Rp 1,155,000 3tb Rp 1,585,000 untuk yang ingin -

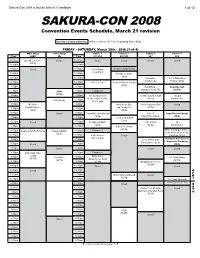

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

Numero Kansi Arvostelut Artikkelit / Esittelyt Mielipiteet Muuta 1 (1/2005

Numero Kansi Arvostelut Artikkelit / esittelyt Mielipiteet Muuta -Full Metal Panic (PAN Vision) (Mauno Joukamaa) -DNAngel (ADV) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Final Fantasy Unlimited (PAN Vision) (Jukka Simola) -Kissankorvanteko-ohjeet (Einar -Neon Genesis Evangelion, 2s (Pekka Wallendahl) - Pääkirjoitus: Olennainen osa animen ja -Jin-Roh (Future Film) (Mauno Joukamaa) Karttunen) -Gainax, 1s (?, oletettavasti Pekka Wallendahl) mangan suosiota on hahmokulttuuri (Jari -Manga! Manga! The world of Japanese comics (Kodansha) (Mauno Joukamaa) -Idän ihmeitä: Natto (Jari Lehtinen) 1 -Megumi Hayashibara, 1s (?, oletettavasti Pekka Wallendahl) Lehtinen, Kyuu Eturautti) -Salapoliisi Conan (Egmont) (Mauno Joukamaa) -Kotimaan katsaus: Animeunioni, -Makoto Shinkai, 2s (Jari Lehtinen) - Kolumni: Anime- ja mangakulttuuri elää (1/2005) -Saint Tail (Tokyopop) (Jari Lehtinen) MAY -Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, 1s (Miika Huttunen) murrosvaihetta, saa nähdä tuleeko siitä -Duel Masters (korttipeli) (Erica Christensen) -Fennomanga-palsta alkaa -Kuukauden klassikko: Saiyuki, 2s (Jari Lehtinen) valtavirta vai floppi (Pekka Wallendahl) -Duel Masters: Sempai Legends (Erica Christensen) -Animea TV:ssä alkaa -International Ragnarök Online (Jukka Simola) -Star Ocean: Till The End Of Time (Kyuu Eturautti) -Star Ocean EX (Geneon) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Neon Genesis Evangelion (PAN Vision) (Mikko Lammi) - Pääkirjoitus: Cosplay on harrastajan -Spiral (Funimation) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Cosplay, 4s (Sefie Rosenlund) rakkaudenosoitus (Mauno Joukamaa) -Hopeanuoli (Future Film) (Jari Lehtinen) -

Rediscovering Our Humanity: How the Posthuman Noir Anime, Darker Than Black, Subverts the Tropes of Film Noir to Reaffirm a Humanist Agenda

CINEMA 7! 131 REDISCOVERING OUR HUMANITY: HOW THE POSTHUMAN NOIR ANIME, DARKER THAN BLACK, SUBVERTS THE TROPES OF FILM NOIR TO REAFFIRM A HUMANIST AGENDA Maxine Gee (University of York) I intended to reason. This passion is detrimental to me.... — Mary Shelly1 There is an inherent contradiction at the heart of posthuman noir; this sub-genre focuses on science fictional futures where certain characters have moved beyond the traditional boundaries of what is considered human; these posthumans are modified for perfection, often presented as more logical and rational than their human counterparts. However, the emphasis, in all of the Anglo-American films and Japanese anime included in the posthuman noir corpus, is on more typically human traits of emotion and irrationality and their awakening/re-awakening in these posthuman characters. This hints that the sub- genre is not in fact positing a truly posthumanist standpoint but reaffirming an older humanist one, assuaging fears that what is traditionally considered human has no place in these technologically advanced worlds. This article will explore this theory through its application to one posthuman noir Japanese anime, Tensai Okamura’s Darker Than Black (2007), a series which is indicative of the other Anglo-American films and Japanese anime included in the posthuman noir corpus between 1982 and 2012. Darker Than Black, which aired for 26 episodes between April and September 2007, was produced by animation studios Bones and Aniplex. It was followed by a shorter second series of 13 episodes in 2009 and an OVA (original video animation) of four episodes in 2010. The analysis in this article will concentrate on the first series of Darker Than Black.