The HERPETOLOGICAL BULLETIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low Res, 906 KB

Copyright: © 2011 Janzen and Bopage. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 5(2):1-13. provided the original author and source are credited. The herpetofauna of a small and unprotected patch of tropical rainforest in Morningside, Sri Lanka 1,3PETER JANZEN AND 2MALAKA BOPAGE 1Rheinallee 13, 47119 Duisburg, GERMANY 2Biodiversity Education & Exploration Society (BEES) 63/c Wackvella road Galle 80000, SRI LANKA Abstract.—Morningside is an exceptional area in Sri Lanka with highly endemic herpetofauna. How- ever, this relictual forest area lies inside a tea plantation and is mostly lacking conservation protec- tion. Species inventories of remaining rainforest patches are currently incomplete, and information about the behavior and ecology of the herpetofauna of Morningside is poorly known. In our survey, we identified 13 amphibian species and recorded an additional two species that could not be identi- fied with existing keys. We determined 11 reptile species from this patch of forest, and another un- identifiedCnemaspis gecko was recorded. We did not assess the herpetofauna outside of this forest patch. Some species are described for the first time in Morningside, suggesting a wider distribution in Sri Lanka. We also document a call from a male Pseudophilautus cavirostris for the first time. Perspectives for future surveys are given. Key words. Survey, Morningside, Sri Lanka, herpetofauna, conservation, Pseudophilautus cavirostris Citation: Jansen, P. and Bopage, M. 2011. The herpetofauna of a small and unprotected patch of tropical rainforest in Morningside, Sri Lanka. -

THE SNAKES of SURINAM, PART XVI: SUBFAMILY XENO- By: A

-THE SNAKES -OF SURINAM, ---PART XVI: SUBFAMILY --XENO- DONTINAE ( GENERA WAGLEROPHIS., XENODON AND XENO PHOLIS). By: A. Abuys, Jukwerderweg 31, 9901 GL Appinge dam, The Netherlands. Contents: The genus WagZerophis - The genus Xeno don - The genus XenophoZis - References. THE GENUS wAGLEROPHIS ROMANO & HOGE, 1972 This genus contains only one species. Prior to 1972 this species was known as Xenodon merremii (Wagler, 1824). This species is found in Surinam. General data for the genus: Head: The head is short and slightly flattened. The strong neck is only marginally narrower than the head. The relatively large eyes have round pupils. Body: Short and stout with smooth scales. The scales have one apical groove. The formation of the dorsal scales is characteristic for this genus. These are arranged so that the upper rows are at an angle to the lower ones (see figure 1) . Tail: Short. Behaviour: Terrestrial and both nocturnal and di urnal. Food: Frogs, toads, lizards and sometimes snakes, insects or small mammals. Habitat: Damp forest floors near swamps or water. Reproduction: Oviparous. Remarks: When threatened or disturbed, the fore part of the body is inflated and the neck is spread in a cobra-like fashion. The head is al· so raised slightly, but not as high and as 181 Fig. 1. Dorsal scale pattern of Waglerophis. From: Peters & Orejas-Miranda, 1970. vertically as a cobra. This is an aggressive snake which will invariably resort to biting if the warning behaviour described above is not heeded. This genus (in common with the genera Xenodon, Heterodon and Lystrophis) has two enlarged teeth attached to the back of the upper jaw. -

The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M

The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M. Cei Instituto de Biología Animal Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Casilla Correo 327 Mendoza, Argentina Reprinted from: Duellman, William E. (ed.). 1979. The South American Herpetofauna: Its origin, evolution, and dispersal. Univ. Kansas Mus. Nat. Hist. MonOgr. 7: 1-485. Copyright © 1979 by The Museum of Natural History, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. 13. The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M. Cei Instituto de Biología Animal Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Casilla Correo 327 Mendoza, Argentina The word Patagonia is derived from the longed erosion. Scattered through the region term “Patagones,” meaning big-legged men, are extensive areas of extrusive basaltic rocks. applied to the tall Tehuelche Indians of The open landscape is dissected by transverse southernmost South America by Ferdinand rivers descending from the snowy Andean Magellan in 1520. Subsequently, this pic cordillera; drainage is poor near the Atlantic turesque name came to be applied to a con coast. Patagonia is subjected to severe sea spicuous continental region and to its biota. sonal drought with about five cold winter Biologically, Patagonia can be defined as months and a cool dry summer, infrequently that region east of the Andes and extending interrupted by irregular rains and floods. southward to the Straits of Magellan and eastward to the Atlantic Ocean. The northern boundary is not so clear cut. Elements of the HISTORY OF THE PATAGONIAN BIOTA Pampean biota penetrate southward along the coast between the Rio Colorado and the Rio In contrast to the present, almost uniform Negro (Fig. 13:1). Also, in the west Pata steppe associations in Rio Negro, Chubut, gonian landscapes and biota enter the vol and Santa Cruz provinces, during Oligocene canic regions of southern Mendoza, almost and Miocene times tropical and subtropical reaching the Rio Atuel Basin. -

Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands

Zoological Studies 56: 38 (2017) doi:10.6620/ZS.2017.56-38 Open Access Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands Tein-Shun Tsai1,* and Jean-Jay Mao2 1Department of Biological Science and Technology, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology 1 Shuefu Road, Neipu, Pingtung 912, Taiwan 2Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, National Ilan University No.1, Sec. 1, Shennong Rd., Yilan City, Yilan County 260, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 28 August 2017; Accepted 25 November 2017; Published 19 December 2017; Communicated by Jian-Nan Liu) Tein-Shun Tsai and Jean-Jay Mao (2017) Shed snake skins have many applications for humans and other animals, and can provide much useful information to a field survey. When properly prepared and identified, a shed snake skin can be used as an important voucher; the morphological descriptions of the shed skins may be critical for taxonomic research, as well as studies of snake ecology and conservation. However, few convenient/ expeditious methods or techniques to identify shed snake skins in specific areas have been developed. In this study, we collected and examined a total of 1,260 shed skin samples - including 322 samples from neonates/ juveniles and 938 from subadults/adults - from 53 snake species in Taiwan and adjacent islands, and developed the first guide to identify them. To the naked eye or from scanned images, the sheds of almost all species could be identified if most of the shed was collected. The key features that aided in identification included the patterns on the sheds and scale morphology. -

(Gloydius Blomhoffii) Antivenom in Japan, Korea, and China

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 59, 20-24, 2006 Original Article Standardization of Regional Reference for Mamushi (Gloydius blomhoffii) Antivenom in Japan, Korea, and China Tadashi Fukuda*, Masaaki Iwaki, Seung Hwa Hong1, Ho Jung Oh1, Zhu Wei2, Kazunori Morokuma3, Kunio Ohkuma3, Lei Dianliang4, Yoshichika Arakawa and Motohide Takahashi Department of Bacterial Pathogenesis and Infection Control, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo 208-0011; 3First, Production Department, Chemo-Sero-Therapeutic Research Institute, Kumamoto 860-8568, Japan; 1Korea Food and Drug Administration, Soul 122-704, Korea; 2Shanghai Institute of Biological Products, Shanghai 200052; and 4Department of Serum, National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products, Beijing 10050, People’s Republic of China (Received June 27, 2005. Accepted November 11, 2005) SUMMARY: The mamushi (Gloydius blomhoffii) snakes that inhabit Japan, Korea, and China produce venoms with similar serological characters to each other. Individual domestic standard mamushi antivenoms have been used for national quality control (potency testing) of mamushi antivenom products in these countries, because of the lack of an international standard material authorized by the World Health Organization. This precludes comparison of the results of product potency testing among countries. We established a regional reference antivenom for these three Asian countries. This collaborative study indicated that the regional reference mamushi antivenom has an anti-lethal titer of 33,000 U/vial and anti-hemorrhagic titer of 36,000 U/vial. This reference can be used routinely for quality control, including national control of mamushi antivenom products. reference antivenom. INTRODUCTION In the present study, the potency of a candidate regional Snakebites are a threat to human life in areas inhabited by reference mamushi antivenom produced by Shanghai Insti- poisonous snakes. -

Caderno De Resumos EHFB 2015

Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes Tatiana Tavares da Silva Rosa Andrea Lopes de Souza (Organizadoras) Anais do Encontro de História e Filosofia da Biologia 2015 São Paulo Instituto de Biociências (IB/USP) 2015 Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes Tatiana Tavares da Silva Rosa Andrea Lopes de Souza (Organizadoras) Anais do Encontro de História e Filosofia da Biologia 2015 Instituto de Biociências Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo 29 a 31 de julho de 2015 Promoção: ABFHiB, Associação Brasileira de Filosofia e His- tória da Biologia Apoio: Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo (IB-USP) Núcleo de Pesquisa em Educação, Divulgação e Epistemologia da Evolução (EDEVO-Darwin) Laboratório de História da Biologia e Ensino (IB-USP) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Genética e Biologia Evolutiva) do IB-USP Programa de Pós-Graduação Interunidades em Ensino de Ciências da USP Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) ENCONTRO DE HISTÓRIA E FILOSOFIA DA BIOLOGIA 2015 São Paulo, 29 a 31 de agosto de 2015 LOCAL: Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo – Edifício Félix Kurt Rawitsher (“Minas”) PROMOÇÃO: Associação Brasileira de Filosofia e História da Biologia (ABFHiB) http://www.abfhib.org COMISSÃO ORGANIZADORA: Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes (IB-USP) Nelio Bizzo (FE-USP) Maurício de Carvalho Ramos (FFLCH-USP) Hamilton Haddad (IB-USP) COMISSÃO CIENTÍFICA: Aldo M. de Araújo (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul) Ana Maria de Andrade Caldeira (Universidade Estadual Paulista) Anna Carolina Regner -

Herp. Bulletin 101.Qxd

Mountain wolf snake ( Lycodon r . ruhstrati ) predation on an exotic lizard, Anolis sagrei , in Chiayi County, Taiwan GERRUT NORVAL 1, SHAO-CHANG HUANG 2 and JEAN-JAY MAO 3 1 Applied Behavioural Ecology & Ecosystem Research Unit, Department of Nature Conservation, UNISA, Private Bag X6, Florida, 1710, Republic of South Africa . Email: [email protected] [author for correspondence] 2 Department of Life Science, Tunghai University. No. 181, Sec. 3, Taichung-Kan Road, Taichung, 407- 04, Taiwan, R.O.C . 3 Department of Natural Resources, National I-Lan University, No. 1, Shen-Lung Rd., Sec. 1, I-Lan City 260, Taiwan, R.O.C . ABSTRACT – The Mountain wolf snake ( Lycodon ruhstrati ruhstrati ) is a common snake species at low elevations all over Taiwan. Still, it appears to be poorly studied in Taiwan and adjacent areas since little has been reported about this species. On 26 th August 2002 ten L. r. ruhstrati eggs were obtained from an adult female, one of two that were caught a day before, and eight of the eggs hatched successfully on 14 th October 2002. While in captivity all the adults preyed upon Anolis sagrei , which were given to them as prey, while two neonates accepted A. sagrei hatchlings offered to them as food. On February 18 th , 2006, a DOR Mountain wolf snake, with an A. sagrei in its stomach, was found on a tarred road in Santzepu, Sheishan District, Chiayi County. This appears to be the first report from Taiwan of the Mountain wolf snake ( L. r. ruhstrati ) preying on the exotic introduced lizard A. -

Ecology, Behavior and Conservation of the Japanese Mamushi Snake, Gloydius Blomhoffii: Variation in Compromised and Uncompromised Populations

ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS By KIYOSHI SASAKI Bachelor of Arts/Science in Zoology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 1999 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2006 ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS Dissertation Approved: Stanley F. Fox Dissertation Adviser Anthony A. Echelle Michael W. Palmer Ronald A. Van Den Bussche A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sincerely thank the following people for their significant contribution in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. I could never have completed this work without their help. Dr. David Duvall, my former mentor, helped in various ways until the very end of his career at Oklahoma State University. This study was originally developed as an undergraduate research project under Dr. Duvall. Subsequently, he accepted me as his graduate student and helped me expand the project to this Ph.D. research. He gave me much key advice and conceptual ideas for this study. His encouragement helped me to get through several difficult times in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. He also gave me several books as a gift and as an encouragement to complete the degree. Dr. Stanley Fox kindly accepted to serve as my major adviser after Dr. Duvall’s departure from Oklahoma State University and involved himself and contributed substantially to this work, including analysis and editing. -

Reptile Diversity in Beraliya Mukalana Proposed Forest Reserve, Galle District, Sri Lanka

TAPROBANICA, ISSN 1800-427X. April, 2012. Vol. 04, No. 01: pp. 20-26, 1 pl. © Taprobanica Private Limited, Jl. Kuricang 18 Gd.9 No.47, Ciputat 15412, Tangerang, Indonesia. REPTILE DIVERSITY IN BERALIYA MUKALANA PROPOSED FOREST RESERVE, GALLE DISTRICT, SRI LANKA Sectional Editor: John Rudge Submitted: 13 January 2012, Accepted: 02 March 2012 D. M. S. Suranjan Karunarathna1 and A. A. Thasun Amarasinghe2 1 Young Zoologists’ Association of Sri Lanka, Department of National Zoological Gardens, Dehiwala, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] 2 Komunitas Konservasi Alam Tanah Timur, Jl. Kuricang 18 Gd.9 No.47, Ciputat 15412, Tangerang, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Beraliya Mukalana Proposed Forest Reserve (BMPFR) is a fragmented lowland rainforest patch in Galle District, Sri Lanka. During our two-year survey we recorded a total of 66 species of reptile (28 Lizards, 36 Snakes and 2 Tortoises), which represents 31.4 % of the total Sri Lankan reptile fauna. Thirty-five of the species are endemic to Sri Lanka. Of the recorded 66 species, 1 species is Critically Endangered, 3 are Endangered, 6 are Vulnerable, 14 are Near-threatened and 4 are Data-deficient. This important forest area is threatened by harmful anthropogenic activities such as illegal logging, use of chemicals and land-fill. Environmental conservationists are urged to focus attention on this Wet-zone forest. Key words: Endemics, species richness, threatened, ecology, conservation, wet-zone. Introduction Beraliya Mukalana Proposed Forest Reserve Study Area: The Beraliya Mukalana Proposed (BMPFR) is an important forest area in Galle Forest Reserve (BMPFR) area belongs to Alpitiya District, in the south of Sri Lanka. -

Including Covers

ISSUE 22, PUBLISHEDAustralasian 1 JournalJULY of2014 Herpetology 1 ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) AustralasianAustralasian JournalJournal ofof HerpetologyHerpetology Contents: File snakes, new species, pp. 2-8. Hoser 2013 - Australasian Journal of Herpetology 18:2-79. DraconinaeAvailable reclassified, online at www.herp.net pp. 9-59. NewCopyright- turtles, Kotabi pp. Publishing 60-64. - All rights reserved Australasian Journal of Herpetology Australasian2 Journal of Herpetology 22:2-8. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) Published 1July 2014. ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) A break up of the genus Acrochordus Hornstedt, 1787, into two tribes, three genera and the description of two new species (Serpentes: Acrochordidae). RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: [email protected] Received 2 January 2014, Accepted 21 May 2014, Published 1 July 2014. ABSTRACT This paper presents a revised taxonomy for the living Acrochordidae. The species Acrochordus javanicus Hornstedt, 1787 divided by McDowell in 1979 into two species is further divided, with two new species from south-east Asia formally named for the first time. The taxon A. arafurae McDowell, 1979 is placed in a separate genus, named for the first time. A. granulatus Schneider, 1799 is placed in a separate genus, for which the name Chersydrus Schneider, 1801 is already available. Keywords: Taxonomy; Australasia; Asia; Acrochordus; Chersydrus; new genus; Funkiacrochordus; new tribes; Acrochordidini; Funkiacrochordidini; new subgenus: Vetusacrochordus; new species; malayensis; mahakamiensis. INTRODUCTION Wüster, Mark O’Shea, David John Williams, Bryan Fry and This paper presents a revised taxonomy for the living others posted at: http://www.aussiereptileclassifieds.com/ Acrochordidae. -

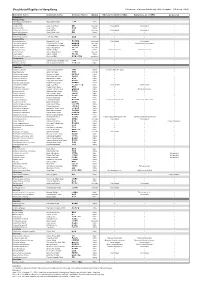

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

2008 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Le Centre Sheraton Montréal Hotel Montréal, Quebec, Canada 23 July 2008 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University Biological Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - OE 167 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 31 May 2008 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 23 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Salon A&B in the Le Centre Sheraton, Montréal Hotel. President Mushinsky plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book. Items that a governor wishes to discuss will be exempted from the motion for blanket acceptance and will be acted upon individually. We will cover the proposed consititutional changes following discussion of reports. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Montreal. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Montréal on 20 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive late on the afternoon of 22 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 27 July 2005 from 1800-2000 h in Salon A&C. Please plan to attend the BOG meeting and Annual Business Meeting. I look forward to seeing you in Montréal. Sincerely, Maureen A. Donnelly ASIH Secretary 1 ASIH BOARD OF GOVERNORS 2008 Past Presidents Executive Elected Officers Committee (not on EXEC) Atz, J.W.