Oligodon Formosanus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Lamprophiidae Fitzinger (Serpentes, Caenophidia)

Zootaxa 1945: 51–66 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Dissecting the major African snake radiation: a molecular phylogeny of the Lamprophiidae Fitzinger (Serpentes, Caenophidia) NICOLAS VIDAL1,10, WILLIAM R. BRANCH2, OLIVIER S.G. PAUWELS3,4, S. BLAIR HEDGES5, DONALD G. BROADLEY6, MICHAEL WINK7, CORINNE CRUAUD8, ULRICH JOGER9 & ZOLTÁN TAMÁS NAGY3 1UMR 7138, Systématique, Evolution, Adaptation, Département Systématique et Evolution, C. P. 26, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 43 Rue Cuvier, Paris 75005, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2Bayworld, P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Rue Vautier 29, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 4Smithsonian Institution, Center for Conservation Education and Sustainability, B.P. 48, Gamba, Gabon. 5Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 6Biodiversity Foundation for Africa, P.O. Box FM 730, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. E-mail: [email protected] 7 Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, University of Heidelberg, INF 364, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 8Centre national de séquençage, Genoscope, 2 rue Gaston-Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry cedex, France. E-mail: www.genoscope.fr 9Staatliches Naturhistorisches Museum, Pockelsstr. 10, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 10Corresponding author Abstract The Elapoidea includes the Elapidae and a large (~60 genera, 280 sp.) and mostly African (including Madagascar) radia- tion termed Lamprophiidae by Vidal et al. -

Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands

Zoological Studies 56: 38 (2017) doi:10.6620/ZS.2017.56-38 Open Access Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands Tein-Shun Tsai1,* and Jean-Jay Mao2 1Department of Biological Science and Technology, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology 1 Shuefu Road, Neipu, Pingtung 912, Taiwan 2Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, National Ilan University No.1, Sec. 1, Shennong Rd., Yilan City, Yilan County 260, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 28 August 2017; Accepted 25 November 2017; Published 19 December 2017; Communicated by Jian-Nan Liu) Tein-Shun Tsai and Jean-Jay Mao (2017) Shed snake skins have many applications for humans and other animals, and can provide much useful information to a field survey. When properly prepared and identified, a shed snake skin can be used as an important voucher; the morphological descriptions of the shed skins may be critical for taxonomic research, as well as studies of snake ecology and conservation. However, few convenient/ expeditious methods or techniques to identify shed snake skins in specific areas have been developed. In this study, we collected and examined a total of 1,260 shed skin samples - including 322 samples from neonates/ juveniles and 938 from subadults/adults - from 53 snake species in Taiwan and adjacent islands, and developed the first guide to identify them. To the naked eye or from scanned images, the sheds of almost all species could be identified if most of the shed was collected. The key features that aided in identification included the patterns on the sheds and scale morphology. -

Molecular Evolution of Three-Finger Toxins in the Long-Glanded Coral Snake Species Calliophis Bivirgatus

toxins Article Electric Blue: Molecular Evolution of Three-Finger Toxins in the Long-Glanded Coral Snake Species Calliophis bivirgatus Daniel Dashevsky 1,2 , Darin Rokyta 3 , Nathaniel Frank 4, Amanda Nouwens 5 and Bryan G. Fry 1,* 1 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] 2 Australian National Insect Collection, Commonwealth Science and Industry Research Organization, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 24105, USA; [email protected] 4 MToxins Venom Lab, 717 Oregon Street, Oshkosh, WI 54902, USA; [email protected] 5 School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected], Tel.: +61-7-336-58515 Abstract: The genus Calliophis is the most basal branch of the family Elapidae and several species in it have developed highly elongated venom glands. Recent research has shown that C. bivirgatus has evolved a seemingly unique toxin (calliotoxin) that produces spastic paralysis in their prey by acting on the voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channels. We assembled a transcriptome from C. bivirgatus to investigate the molecular characteristics of these toxins and the venom as a whole. We find strong confirmation that this genus produces the classic elapid eight-cysteine three-finger toxins, that δ-elapitoxins (toxins that resemble calliotoxin) are responsible for a substantial portion of the venom composition, and that these toxins form a distinct clade within a larger, more diverse clade of C. bivirgatus three-finger toxins. This broader clade of C. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Lamprophiidae Fitzinger (Serpentes, Caenophidia)

Zootaxa 1945: 51–66 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Dissecting the major African snake radiation: a molecular phylogeny of the Lamprophiidae Fitzinger (Serpentes, Caenophidia) NICOLAS VIDAL1,10, WILLIAM R. BRANCH2, OLIVIER S.G. PAUWELS3,4, S. BLAIR HEDGES5, DONALD G. BROADLEY6, MICHAEL WINK7, CORINNE CRUAUD8, ULRICH JOGER9 & ZOLTÁN TAMÁS NAGY3 1UMR 7138, Systématique, Evolution, Adaptation, Département Systématique et Evolution, C. P. 26, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 43 Rue Cuvier, Paris 75005, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2Bayworld, P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Rue Vautier 29, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 4Smithsonian Institution, Center for Conservation Education and Sustainability, B.P. 48, Gamba, Gabon. 5Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 6Biodiversity Foundation for Africa, P.O. Box FM 730, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. E-mail: [email protected] 7 Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, University of Heidelberg, INF 364, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 8Centre national de séquençage, Genoscope, 2 rue Gaston-Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry cedex, France. E-mail: www.genoscope.fr 9Staatliches Naturhistorisches Museum, Pockelsstr. 10, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 10Corresponding author Abstract The Elapoidea includes the Elapidae and a large (~60 genera, 280 sp.) and mostly African (including Madagascar) radia- tion termed Lamprophiidae by Vidal et al. -

Herp. Bulletin 101.Qxd

Mountain wolf snake ( Lycodon r . ruhstrati ) predation on an exotic lizard, Anolis sagrei , in Chiayi County, Taiwan GERRUT NORVAL 1, SHAO-CHANG HUANG 2 and JEAN-JAY MAO 3 1 Applied Behavioural Ecology & Ecosystem Research Unit, Department of Nature Conservation, UNISA, Private Bag X6, Florida, 1710, Republic of South Africa . Email: [email protected] [author for correspondence] 2 Department of Life Science, Tunghai University. No. 181, Sec. 3, Taichung-Kan Road, Taichung, 407- 04, Taiwan, R.O.C . 3 Department of Natural Resources, National I-Lan University, No. 1, Shen-Lung Rd., Sec. 1, I-Lan City 260, Taiwan, R.O.C . ABSTRACT – The Mountain wolf snake ( Lycodon ruhstrati ruhstrati ) is a common snake species at low elevations all over Taiwan. Still, it appears to be poorly studied in Taiwan and adjacent areas since little has been reported about this species. On 26 th August 2002 ten L. r. ruhstrati eggs were obtained from an adult female, one of two that were caught a day before, and eight of the eggs hatched successfully on 14 th October 2002. While in captivity all the adults preyed upon Anolis sagrei , which were given to them as prey, while two neonates accepted A. sagrei hatchlings offered to them as food. On February 18 th , 2006, a DOR Mountain wolf snake, with an A. sagrei in its stomach, was found on a tarred road in Santzepu, Sheishan District, Chiayi County. This appears to be the first report from Taiwan of the Mountain wolf snake ( L. r. ruhstrati ) preying on the exotic introduced lizard A. -

Oligodon Kheriensis Acharji & Ray, 1936, in India and Nepal, with Notes

__All_Short_Notes_ShOrT_NOTE.qxd 12.02.2016 10:24 Seite 15 ShOrT NOTE hErPETOZOA 28 (3/4) Wien, 30. jänner 2016 ShOrT NOTE 181 Oligodon kheriensis AChArji & r Ay , 1936, in india and Nepal, s l m i k a t l 1 with notes on distribution, e r l l l a i i i t e d l l u i i d o o o u z a l d s s s y o o o ecology and conservation o i t e d d d g s s s i i b d e e e v l e e e f n e i a h h h i y y a b b b c y t t t t l l d , r r r p c l n b a b b n u u u o o n n n i a a v t t t l b b i i i r t g n s s s t The Coral-red Kukri Snake, Oligodon a e e c s i i i f f f n s o a c l l l p p i r d d d c d n m x e e e i g kheriensis AChArji & r Ay , 1936, is one of e f n n s s s e , u r n n n t g t t t e e e i c e i i i e e e s e e l t r p p d l e h h h i the rarest snake species worldwide. -

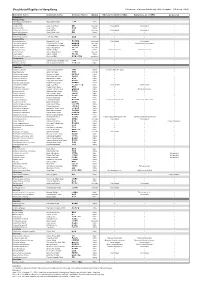

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

P. 1 AC27 Inf. 7 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement

AC27 Inf. 7 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-seventh meeting of the Animals Committee Veracruz (Mexico), 28 April – 3 May 2014 Species trade and conservation IUCN RED LIST ASSESSMENTS OF ASIAN SNAKE SPECIES [DECISION 16.104] 1. The attached information document has been submitted by IUCN (International Union for Conservation of * Nature) . It related to agenda item 19. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC27 Inf. 7 – p. 1 Global Species Programme Tel. +44 (0) 1223 277 966 219c Huntingdon Road Fax +44 (0) 1223 277 845 Cambridge CB3 ODL www.iucn.org United Kingdom IUCN Red List assessments of Asian snake species [Decision 16.104] 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of published IUCN Red List assessments 3 a. Threats 3 b. Use and Trade 5 c. Overlap between international trade and intentional use being a threat 7 3. Further details on species for which international trade is a potential concern 8 a. Species accounts of threatened and Near Threatened species 8 i. Euprepiophis perlacea – Sichuan Rat Snake 9 ii. Orthriophis moellendorfi – Moellendorff's Trinket Snake 9 iii. Bungarus slowinskii – Red River Krait 10 iv. Laticauda semifasciata – Chinese Sea Snake 10 v. -

Reptiles of Phetchaburi Province, Western Thailand: a List of Species, with Natural History Notes, and a Discussion on the Biogeography at the Isthmus of Kra

The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University 3(1): 23-53, April 2003 ©2003 by Chulalongkorn University Reptiles of Phetchaburi Province, Western Thailand: a list of species, with natural history notes, and a discussion on the biogeography at the Isthmus of Kra OLIVIER S.G. PAUWELS 1*, PATRICK DAVID 2, CHUCHEEP CHIMSUNCHART 3 AND KUMTHORN THIRAKHUPT 4 1 Department of Recent Vertebrates, Institut Royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, 29 rue Vautier, 1000 Brussels, BELGIUM 2 UMS 602 Taxinomie-collection – Reptiles & Amphibiens, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 25 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, FRANCE 3 65 Moo 1, Tumbon Tumlu, Amphoe Ban Lat, Phetchaburi 76150, THAILAND 4 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, THAILAND ABSTRACT.–A study of herpetological biodiversity was conducted in Phetcha- buri Province, in the upper part of peninsular Thailand. On the basis of a review of available literature, original field observations and examination of museum collections, a preliminary list of 81 species (12 chelonians, 2 crocodiles, 23 lizards, and 44 snakes) is established, of which 52 (64 %) are reported from the province for the first time. The possible presence of additional species is discussed. Some biological data on the new specimens are provided including some range extensions and new size records. The herpetofauna of Phetchaburi shows strong Sundaic affinities, with about 88 % of the recorded species being also found south of the Isthmus of Kra. A biogeographic affinity analysis suggests that the Isthmus of Kra plays the role of a biogeographic filter, due both to the repeated changes in climate during the Quaternary and to the current increase of the dry season duration along the peninsula from south to north. -

Australasian Journal of Herpetology ISSN 1836-5698 (Print)1 Issue 12, 30 April 2012 ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) Australasian Journal of Herpetology

Australasian Journal of Herpetology ISSN 1836-5698 (Print)1 Issue 12, 30 April 2012 ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) Australasian Journal of Herpetology Hoser 2012 - Australasian Journal of Herpetology 9:1-64. Available online at www.herp.net Contents on pageCopyright- 2. Kotabi Publishing - All rights reserved 2 Australasian Journal of Herpetology Issue 12, 30 April 2012 Australasian Journal of Herpetology CONTENTS ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) A New Genus of Coral Snake from Japan (Serpentes:Elapidae). Raymond T. Hoser, 3-5. A revision of the Asian Pitvipers, referred to the genus Cryptelytrops Cope, 1860, with the creation of a new genus Adelynhoserea to accommodate six divergent species (Serpentes:Viperidae:Crotalinae). Raymond T. Hoser, 6-8. A division of the South-east Asian Ratsnake genus Coelognathus (Serpentes: Colubridae). Raymond T. Hoser, 9-11. A new genus of Asian Snail-eating Snake (Serpentes:Pareatidae). Raymond T. Hoser, 10-12-15. The dissolution of the genus Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922 (Sepentes:Colubrinae). Raymond T. Hoser, 16-17. Three new species of Stegonotus from New Guinea (Serpentes: Colubridae). Raymond T. Hoser, 18-22. A new genus and new subgenus of snakes from the South African region (Serpentes: Colubridae). Raymond T. Hoser, 23-25. A division of the African Genus Psammophis Boie, 1825 into 4 genera and four further subgenera (Serpentes: Psammophiinae). Raymond T. Hoser, 26-31. A division of the African Tree Viper genus Atheris Cope, 1860 into four subgenera (Serpentes:Viperidae). Raymond T. Hoser, 32-35. A new Subgenus of Giant Snakes (Anaconda) from South America (Serpentes: Boidae). Raymond T. Hoser, 36-39. -

The Snake Family Psammophiidae (Reptilia: Serpentes): Phylogenetics and Species Delimitation in the African Sand Snakes (Psammophis Boie, 1825) and Allied Genera

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (2008) 1045–1060 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev The snake family Psammophiidae (Reptilia: Serpentes): Phylogenetics and species delimitation in the African sand snakes (Psammophis Boie, 1825) and allied genera Christopher M.R. Kelly a,*, Nigel P. Barker a, Martin H. Villet b, Donald G. Broadley c, William R. Branch d a Molecular Ecology & Systematics Group, Department of Botany, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa b Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa c Biodiversity Foundation for Africa, P.O. Box FM 730 Bulawayo, Zimbabwe d Bayworld, P.O. Box 13147, Hume wood 6013, South Africa article info abstract Article history: This study constitutes the first evolutionary investigation of the snake family Psammophiidae—the most Received 13 August 2007 widespread, most clearly defined, yet perhaps the taxonomically most problematic of Africa’s family- Revised 11 March 2008 level snake lineages. Little is known of psammophiid evolutionary relationships, and the type genus Accepted 13 March 2008 Psammophis is one of the largest and taxonomically most complex of the African snake genera. Our aims Available online 21 March 2008 were to reconstruct psammophiid phylogenetic relationships and to improve characterisation of species boundaries in problematic Psammophis species complexes. We used approximately 2500 bases of DNA Keywords: sequence from the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, and 114 terminals covering all psammophiid Advanced snakes genera and incorporating approximately 75% of recognised species and subspecies. Phylogenetic recon- Africa Phylogenetics structions were conducted primarily in a Bayesian framework and we used the Wiens/Penkrot protocol Psammophiidae to aid species delimitation. -

A Phylogeny and Revised Classification of Squamata, Including 4161 Species of Lizards and Snakes

BMC Evolutionary Biology This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:93 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-93 Robert Alexander Pyron ([email protected]) Frank T Burbrink ([email protected]) John J Wiens ([email protected]) ISSN 1471-2148 Article type Research article Submission date 30 January 2013 Acceptance date 19 March 2013 Publication date 29 April 2013 Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/93 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2013 Pyron et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes Robert Alexander Pyron 1* * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Frank T Burbrink 2,3 Email: [email protected] John J Wiens 4 Email: [email protected] 1 Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St.