Like a Surgeon Edit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Time Has Come, for You to Lip-Sync, for Your Identity: Bridging the Queer

The Time Has Come, For You to Lip-Sync, For Your Identity: Bridging the Queer Gap Between Theory and Practice Thesis RMA Musicology Vera van Buren (5539307) Feb- Aug 2019 RMA Musicology | Supervisor: Dr. Olga Panteleeva | Second reader: Dr. Judith Peraino Abstract The humanities seem to want to specialize in capturing the human experience in their socio-cultural context. It seems, however, that throughout the past decades, certain experiences are harder to academically pin down than others. The critique posed by queer people on queer theory is one example of this discrepancy. Judith Butler, Maggie Nelson, Sara Ahmed and Crystal Rasmussen are some authors who intellectually capture the experience of queerness. Especially Butler has received critique throughout her career that her description of queerness had very little to do with the real-lived experience of queer people. But, her work showed seminal in the deconstruction of gender identity, as did the works by the other mentioned authors. Despite the important works produced by these authors, it is still difficult to find academic works that are written with a ‘bottom-up’ approach: where the voices of oppressed groups are taken for the truth they speak, while academic references are only there to support their claims. In this thesis, I utilize this ‘bottom-up’ approach, testing through my case study—namely, the experiences of Dutch drag queens, specifically how they experience topics around lip-sync performances—to what extent their lived experience is in accordance with the theoretical works by which they are framed. Through interviews with Dutch drag queens, by attending drag shows, and by critically reviewing academic literature, I will test the discrepancy, or parallel, between the theory, and practice. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

Face to Face AUTUMN 2008

Face to Face AUTUMN 2008 Annie Leibovitz: A Photographer’s Life, 1990 – 2005 Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize 2008 Four Great Portraits My Favourite Portrait by Bill Morris From the Director The Gallery has this year the opportunity to acquire four exceptional portraits for the Collection: Lady Dacre and her son by Hans Eworth – an outstanding and well preserved Tudor portrait; Sir Richard Arkwright by Joseph Wright of Derby (left and cover) – a towering figure in the British Industrial Revolution; Mary Seacole by Albert Challen – a remarkable individual in terms of nineteenth-century army healthcare; and finally Marc Quinn’s Self – the latest of the artist’s self-portrait images, created out of his own blood and frozen. While the Gallery is familiar with raising extra resources for one special portrait at a time, as with the successful appeals for the portraits of John Donne in 2006 or John Fletcher in 2007, these four potential acquisitions pose a great challenge for us. We COVER AND ABOVE Sir Richard Arkwright have some funding already secured, including generous support from the Art Fund by Joseph Wright of Derby, and a contribution from the Gallery’s Portrait Fund, and we are making application to c.1783–85 appropriate external bodies. However, this will leave us with a shortfall and we need substantial help to ensure that we secure these important works for the nation. If you are interested in donating, please contact Emma Black, Individual Giving Manager, on 020 7312 2444 or email her on [email protected]. The article in this issue of Face to Face gives more information. -

Experimenting with Analogy for Lyrics Transformation

WeirdAnalogyMatic: Experimenting with Analogy for Lyrics Transformation Hugo Gonc¸alo Oliveira CISUC, Department of Informatics Engineering University of Coimbra, Portugal [email protected] Abstract Our main goal is thus to explore to what extent we can rely on word embeddings for transforming the semantics This paper is on the transformation of text relying mostly on of a poem, in such a way that its theme shifts according a common analogy vector operation, computed in a distribu- to the seed, while text remains syntactically and semanti- tional model, i.e., static word embeddings. Given a theme, cally coherent. Transforming text, rather than generating it original song lyrics have their words replaced by new ones, related to the new theme as the original words are to the orig- from scratch, should help to maintain the latter. For this, we inal theme. As this is not enough for producing good lyrics, make a rough approximation that the song title summarises towards more coherent and singable text, constraints are grad- its theme and every word in the lyrics is related to this theme. ually applied to the replacements. Human opinions confirmed Relying on this assumption and recalling how analogies can that more balanced lyrics are obtained when there is a one-to- be computed, shifting the theme is a matter of computing one mapping between original words and their replacement; analogies of the kind ‘what is to the new theme as the origi- only content words are replaced; and the replacement has the nal title is to a word used?’. same part-of-speech and rhythm as the original word. -

"MALCOLM X" Screenplay by Arnold Perl, Spike Lee and James Baldwin

"MALCOLM X" Screenplay by Arnold Perl, Spike Lee and James Baldwin (uncredited) Based on the book "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" by Malcolm X and Alex Haley Fourth Draft 1991 FADE IN: EXT. ROXBURY STREET - THE WAR YEARS - DAY It is a bright sunny day on a crowded street on the black side of Boston. PEOPLE and KIDS are busy with their own things. SHORTY bops his way down the street. He is a runty, very dark young man of 21 with a mission and a smile on his face. He wears the flamboyant style of the time: the whole zoot- suit, pegged legs and a wide brim hat with a white feather stuck in the hat band. EXT. STREET - DAY FOLLOW SHOT. Shorty dodges through the crowd with his packages. His smile is one of anticipation. He nods to a PAL without stopping; eyes a COUPLE OF CHICKS dancing on the street, but is not dissuaded. INT. BARBER SHOP - DAY Shorty has his jacket and hat off, his sleeves rolled up. He Script provided for educational purposes. More scripts can be found here: http://www.sellingyourscreenplay.com/library is like a surgeon preparing for an operation. His equipment is spread out on a table: can of lye, large mason jar, wooden stirring spoon, knife, the eggs. His actions have the character of a ritual: each thing being done just so, in time-honored fashion. He slices the potatoes and drops the thin slices into the mason jar. He adds water and makes a paste of the starch. Behind Shorty is a spirited barbershop conversation. -

Karaoke Songs We Can Use As at 22 April 2013

Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. TKS No. SONG TITLE IN THE STYLE OF 21273 Don't Tread On Me 311 25202 First Straw 311 15937 Hey You 311 1325 Where My Girls At? 702 25858 Til The Casket Drops 16523 Bye Bye Baby Bay City Rollers 10657 Amish Paradise "Weird" Al Yankovic 10188 Eat It "Weird" Al Yankovic 10196 Like A Surgeon "Weird" Al Yankovic 18539 Donna 10 C C 1841 Dreadlock Holiday 10 C C 16611 I'm Not In Love 10 C C 17997 Rubber Bullets 10 C C 18536 The Things We Do For Love 10 C C 1811 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 24657 Hot And Wet 112/ Ludacris 21399 We Are One 12 Stones 19015 Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Company 26221 Countdown 2 Chainz/ Chris Brown 15755 You Know Me 2 Pistols & R Jay 25644 She Got It 2 Pistols/ T Pain/ Tay Dizm 15462 Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down 23044 Everytime You Go 3 Doors Down 24923 Here By Me 3 Doors Down 24796 Here Without You 3 Doors Down 15921 It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down 15820 Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down 25232 Let Me Go 3 Doors Down 22933 When You're Young 3 Doors Down 15455 Don't Trust Me 3 Oh!3 21497 Double Vision 3 Oh!3 15940 StarStrukk 3 Oh!3 21392 My First Kiss 3 Oh!3 / Ke$ha 23265 Follow Me Down 3 Oh!3/ Neon Hitch 20734 Starstrukk 3 Oh3!/ Katy Perry 10816 If I'd Been The One 38 Special 10112 What's Up 4 Non Blondes 9628 Sukiyaki 4.pm 15061 Amusement Park 50 Cent 24699 Candy Shop 50 Cent 12623 Candy Shop 50 Cent 1 Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

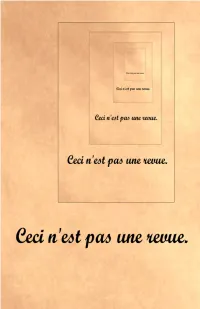

Ceci N'est Pas Une Revue

Ceci n’est pas une revue National English Honor Society of Gulf High School 2011-2012 Literary Magazine Special thanks to Ms. Ledman and Ms. Winslow. Edited by Oliver Chang, Alexander Cranford, Katrina Enoch, Jeffrey Kruse, Elizabeth Mapes, Jeremy Ong, Naser Shareef and Joseph Sylvester This magazine can be found online at: http://goo.gl/BSxYH Contents Egocentrism Doesn’t Become You by Brittany Adams........1 Fire by Katherine Berryman......................3 An Ode to the Forgotten by Alexis Beucler..............4 Woman with a Parasol Ekphrastic by Ruhaani Bhula.........5 An ode—Grey by Nathan Binder...................6 Six Word Memoirs by Bobek, Kane, and Salamilao..........7 Brushes With Life by Caitlyn Borden.................8 Question by Jacqueline Chung..................... 10 Surfaces of Knowledge by Alexander Cranford............ 12 Head in the Clouds by Alexandria Curtwright............ 13 A Lisper’s Woes by Drew Eglin.................... 14 I’m Listening (Perhaps That’s the Problem) by Katrina Enoch.... 15 Untitled by Brittany Gervasi...................... 18 Pictures by Kendra Jones........................ 20 The Evolution of Man by Kristina Kanaan.............. 22 Ode to a Longboard by Michael Keller................ 24 Ode to Coffee by Calee King...................... 25 Ode to Hunting by Carl Krondahl................... 26 Ode to Dreams by Philip Kubiszyn.................. 27 November by Savannah Law...................... 28 You Dita Von Tease Me by Chelsi Mackin............... 29 The Slug by Mouzel Manugas..................... 30 Among the Heaps by Nicole Manugas................. 31 Isolation by Jerad McMickle...................... 32 What’s Important? by Jon Morgan................... 33 America Youth by Corey Palermo................... 35 Ode to My Paper by Devon Ritter................... 37 Untitled Slam! Poem by Nicole Payne................. 39 Ode to Bubbles by Brittany Reid................... -

Rodrigo Ribeiro Barreto.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO E CULTURA CONTEMPORÂNEAS A FABRICAÇÃO DO ÍDOLO POP: A ANÁLISE TEXTUAL DE VIDEOCLIPES E A CONSTRUÇÃO DA IMAGEM DE MADONNA RODRIGO RIBEIRO BARRETO Salvador 2005 2 RODRIGO RIBEIRO BARRETO A FABRICAÇÃO DO ÍDOLO POP: A ANÁLISE TEXTUAL DE VIDEOCLIPES E A CONSTRUÇÃO DA IMAGEM DE MADONNA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporâneas, Faculdade de Comunicação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporâneas. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Wilson da Silva Gomes Salvador 2005 3 AGRADECIMENTOS A meu pai e minha mãe, pela paciência, apoio e carinho ilimitados. A Rosana e Luís Roberto, minha irmã e meu irmão sempre presentes. A Gabriela, a Greice e Ludmila, não podia desejar melhores companheiras de pesquisa. A Luiz, Romulo, Cristiano, Roger, Felix, Sergio e Biagio, que, na hora do aperto, tornaram menos sofrido o percurso de elaboração da dissertação. Aos professores Wilson Gomes – meu orientador oficial há quase cinco anos –, Maria Carmem Jacob de Souza, José Benjamim Picado, Jeder Janotti Jr. e José Francisco Serafim, cujas orientações eventuais foram imprescindíveis para o meu trajeto de pesquisa. Ao Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), que viabilizou minha pesquisa com a oferta de bolsa durante o Mestrado. 4 RESUMO A trajetória videográfica de Madonna, iniciada há mais de 20 anos, confunde-se com o próprio desenvolvimento do videoclipe, cuja consolidação aconteceu também a partir dos anos 1980. Desde então, a contínua popularidade da artista deu a ela e a seus colaboradores respaldo para executar inovações tanto estilísticas quanto temáticas neste formato. -

Perfection Achieved (But Nobody Seems to Care)

FEBRUARY 2018 # 18 Upfront In My View In Practice Sitting Down With Statins for PTA for post-LASIK SICS - another feather Walter Sekundo, vitrectomy surgery ectasia: pro and con in your cap? a.k.a., Mr. SMILE 12 14 – 17 28 – 32 48 – 50 Perfection Achieved (but Nobody Seems to Care) There’s a gold-standard procedure for pterygium surgery, so why are people ignoring it? 18–25 NORTH AMERICA www.theophthalmologist.com 100 MILLION IMPLANTED WORLDWIDE Only MOMENTS MADE. withAcrySof Thanks to you, AcrySof ® IOLs have created more memories than any other lens. Over the last 25 years, the AcrySof®SRUWIROLRRIPRQRIRFDOWRULFDQGPXOWLIRFDOΖ2/VKDVEHHQFKRVHQZLWKFRQȴGHQFH Ask your Alcon representative what makes AcrySof® the most implanted lens in the world*. $OFRQGDWDRQȴOH © 2017 Novartis 10/17 US-ACR-17-E-2756 Image of the Month The Astrocyte Fight Against Glaucoma This confocal microscopy image features the delicate neurovascular plexus of the inner retina, and shows retinal ganglion cells (green), astrocytes (red) and vascular endothelial cells (white) in the inner retina of a rat. This image was taken in the Sivak lab at the Krembil Research Institute, University Health Network and University of Toronto School of Medicine, Canada, and forms part of multi-center research project that has identified that lipoxins – lipid inflammatory mediators – secreted by astrocytes can protect against retinal ganglion cell degeneration in rodent models of glaucoma. I Livne-Bar et al., J Clin Invest, [Epub ahead of print], (2017). PMID: 29106385. Credit: Xiaxin Guo -

SF20 Song List Example

INITIAL Song List CPFC SONGFEST 2020 Song List THE CHIA PET FAN CLUB AND FRIENDS Theme Choice: DOCTORS/HOSPITAL Group Leadership Music Director(s): Harmony Smith Music Selections 1. Like a Surgeon 2. Gaston 3. Lookin’ for the Answer 4. Step by Step 5. Bad Case of Loving You (Doctor, Doctor) Comments • None of these songs will be performed in their entirety, as they’re all too long. • We’re thinking about requesting a minor lyric change for “Gaston”, since the name of the character that the song refers to may or may not end up actually being “Gaston”. We’re looking for a clever rhyme. Song Information and Original Lyrics 1. LIKE A SURGEON Composer(s)/Lyricist(s): Tom Kelly, Weird Al Yankovic Performer(s): Madonna, Weird Al Yankovic From: Notes: Parody of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” (with Weird Al’s lyrics) YouTube: https://youtu.be/notKtAgfwDA I finally made it through med school Somehow I made it through I'm just an intern I still make a mistake or two I was last in my class Barely passed at the institute Now I'm trying to avoid, yah I'm trying to avoid A malpractice suit Hey, like a surgeon Cuttin' for the very first time Like a surgeon Organ transplants are my line Better give me all your gauze nurse This patient's fading fast Complications have set in Don't know how long he'll last Let me see, that I.V. Here we go - time to operate I'll pull his insides out, pull his insides out And see what he ate Songfest ‘20 Song List - 1 INITIAL Song List CPFC Like a surgeon, hey Cuttin' for the very first time Like a surgeon Here's a waiver for you to sign Woe, woe, woe Woe, woe, woe Woe, woe, woe It's a fact - I'm a quack The disgrace of the A.M.A. -

Where Do You Go? Searching for Context in the Music Curriculum

Title: Where Did You Come From? Where Do You Go? Searching for Context in the Music Curriculum Author(s): Kari K. Veblen, Claire W. McCoy, and Janet R. Barrett Source: Veblen, K. K., McCoy, C. W., & Barrett, J. R. (1995, Fall). Where did you come from? Where do you go? Searching for context in the music curriculum. The Quarterly, 6(3), pp. 46-56. (Reprinted with permission in Visions of Research in Music Education, 16(6), Autumn, 2010). Retrieved from http://www-usr.rider.edu/~vrme/ Visions of Research in Music Education is a fully refereed critical journal appearing exclusively on the Internet. Its publication is offered as a public service to the profession by the New Jersey Music Educators Association, the state affiliate of MENC: The National Association for Music Education. The publication of VRME is made possible through the facilities of Westminster Choir College of Rider University Princeton, New Jersey. Frank Abrahams is the senior editor. Jason D. Vodicka is editor of the Quarterly historical reprint series. Chad Keilman is the production coordinator. The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning is reprinted with permission of Richard Colwell, who was senior consulting editor of the original series. Where Did You Cc-rrre Frotn.?Where Do You Go? Searching For Context In The Music Curriculu:lll By Kari K. Veblen, Claire W. McCoy and Janet R. Barrett ven in our increasingly mobile and and characteristic motives. Perceived simi- electronically networked society, geo- larities and differences influence how deeply E graphical origins and birthplaces con- we respond to a new piece, how likely we tinue to fascinate us.