The Simplicity of Nichiren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lotus Sutra: the True Nature of the Buddha

Main | Other Chinese Web Sites Chinese Cultural Studies: The Lotus Sutra: The True Nature of the Buddha from Edward Conze, ed., Buddhist Texts through the Ages, (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1964), pp 142-143, repr in Albert M. Craig, et al, The Heritage of World Civilizations, 2d ed., (New York: Macmillan, 1990), p. 310 [Craig Introduction] The Lotus Sutra (Saddharmapundarikasutra), "Lotus of the True Dharma" is one of the best-loved sacred texts of Mahayana Buddhism. Its original Sanskrit text was translated many times into Chinese (the earliest being in 225 CE), as well as into Tibetan and other languages. The following passage is key one for the development of the idea of the cosmic form of the Buddha. Note that "Tathagata" "(which means "Thus Gone", ie, having achieved Nirvana) is one of the titles of Buddha. Fully enlightened for ever so long, the Tathagata has an endless span of life, he lasts for ever. Although the Tathagata has not entered Nirvana, he makes a show of entering Nirvana, for the sake of those who have to be educated. And even today my ancient course as a Bodhisattva is still incomplete, and my life span is not yet ended. From today onwards still twice as many hundreds of thousands of Nayutas of Kotis of aeons must elapse before my life span is complete. Although therefore I do not at present enter into Nirvana (or extinction), nevertheless I announce my Nirvana. For by this method I bring beings to maturity. Because it might be that, if I stayed here too long and could be seen too often, beings who have performed no meritorious actions, who are without merit, a poorly lot, eager for sensuous pleasures, blind, and wrapped in the net of false views, would, in the knowledge that the Tathagata stays (here all the time), get the notion that life is a mere sport, and would not conceive the notion that the (sight of the) Tathagata is hard to obtain. -

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

The Saddharmapurdarikaas the Prediction

The JapaneseAssociationJapanese Association of Indian and Buddhist Studies Journal oflndian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 64, No. 3, March 2016 (113) The Saddharmapurdarika as the Prediction ofAll the Sentient Beings' Attaining Buddhahood: With Special Focus on the Sadaparibhata-parivarta SuzuKi Takayasu 1. The Aim ofThis Paper While the Saddharmapu4darika (Lotus SUtra, SP) repeatedly teaches that any person who speaks against the SP or against those who keep, read, preach, or explain the SP must experience severe retribution, it also teaches that those who keep, read, preach, or explain the SP shall attain a perfection of the six sense organs, i.e., eye, ear, nose, tongue, bodM and mind. These understandings have been considered the basis of the i] fo11owing teaching in Chapter lg ofthe SP (Sada'paribhUta-parivarta, SP 19): ' There once existed a Bodhisattva named SadaparibhUta. He did not read or preach any Buddhist scripture at all, but only continued to give prediction of attaining buddhahood to all the Buddhists who held the mistaken idea that they had already attainedenlightenment. ' Because ofhis prediction he was abused by them. ' They went to hell on the grounds of having abused him. The now arises: question ' Why did they have to experience such severe retribution for abusing Sada- paribhUta who did not read or preach the SP. To this question the fbllowing interpretation has been general: ' The SP is the prediction of all the sentient beings' attaining buddhahood. Through giving of this prediction to the Buddhists SadaparibhUta had essentially read and preached the SP. It is true that Chapter lo of the 5P predicts that all the sentient beings can attain buddhahood. -

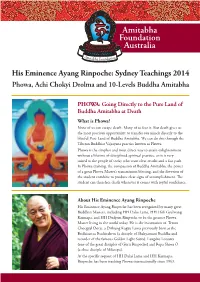

Phowa Teaching 2014

Amitabha Foundation Australia His Eminence Ayang Rinpoche: Sydney Teachings 2014 Phowa, Achi Chokyi Drolma and 10-Levels Buddha Amitabha PHOWA: Going Directly to the Pure Land of Buddha Amitabha at Death What is Phowa? None of us can escape death. Many of us fear it. But death gives us the most precious opportunity: to transfer our minds directly to the blissful Pure Land of Buddha Amitabha. We can do this through the Tibetan Buddhist Vajrayana practice known as Phowa. Phowa is the simplest and most direct way to attain enlightenment without a lifetime of disciplined spiritual practice, so it is very suited to the people of today who want clear results and a fast path. In Phowa training, the compassion of Buddha Amitabha, the power of a great Phowa Master’s transmission blessing, and the devotion of the student combine to produce clear signs of accomplishment. e student can then face death whenever it comes with joyful condence. About His Eminence Ayang Rinpoche His Eminence Ayang Rinpoche has been recognized by many great Buddhist Masters, including HH Dalai Lama, HH 16th Gyalwang Karmapa, and HH Dudjom Rinpoche to be the greatest Phowa Master living in the world today. He is the incarnation of Terton Choegyal Dorje, a Drikung Kagyu Lama previously born as the Bodhisattva Ruchiraketu (a disciple of Shakyamuni Buddha and recorder of the famous Golden Light Sutra), Langdro Lotsawa (one of the great disciples of Guru Rinpoche) and Repa Shiwa Ö (a close disciple of Milarepa). At the specic request of HH Dalai Lama and HH Karmapa, Rinpoche has been teaching Phowa internationally since 1963. -

THE RELIGIOUS and SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE of CHENREZIG in VAJRĀYANA BUDDHISM – a Study of Select Tibetan Thangkas

SSamaama HHaqaq National Museum Institute, of History of Art, Conservation and Museology, New Delhi THE RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF CHENREZIG IN VAJRĀYANA BUDDHISM – A Study of Select Tibetan Thangkas INTRODUCTION he tradition of thangkas has earned itself the merit of pioneering Tibetan art in the 21st century. The purpose behind the effulgent images Tis not to simply lure worshippers with their exuberant colours and designs; it also follows an intricate system of iconometric and iconologic principles in order to beseech the benefaction of a particular deity. As a result, a thangka is worshipped as a didactic ‘visual aid’ for Tibetan Buddhist reli- gious practices. Tracing the origin of the artistic and socio-cultural practices behind a thangka recreates a texture of Central Asian and Indian influences. The origin of ceremonial banners used all across Central Asia depicts a similar practice and philosophy. Yet, a close affinity can also be traced to the Indian art of paṭa painting, which was still prevalent around the eastern province of India around the Pala period.1) This present paper discusses the tradition of thangka painting as a medium for visualisation and a means to meditate upon the principal deity. The word thangka is a compound of two words – than, which is a flat surface and gka, which means a painting. Thus, a thangka represents a painting on a flat sur- 1) Tucci (1999: 271) “Pata, maṇḍala and painted representation of the lives of the saints, for the use of storytellers and of guides to holy places, are the threefold origin of Tibetan tankas”. -

The Lotus Sutra: Opening the Way for the Enlightenment of All People

The Lotus Sutra: Opening the Way for the Enlightenment of All People he Great Teacher T’ien-t’ai of China disciples known as voice-hearers and cause- analyzed the content and meaning of awakened ones), women and evil persons from all the Buddhist sutras, concluding the possibility of ever becoming Buddhas. And Tthat the Lotus Sutra constitutes the highest even for those considered capable of attaining essence of Buddhist teachings. Buddhahood, the pre-Lotus Sutra teachings He classified the Lotus Sutra as conveying presume that the process of doing so requires the teachings that Shakyamuni Buddha countless lifetimes of austere practice. There expounded toward the end of his life, which is no recognition that an ordinary person can the Buddha intended to be passed on to the attain Buddhahood in this single lifetime. The future for the enlightenment of all people. Lotus Sutra, on the other hand, makes clear T’ien-t’ai also pointed out that teachings the that all people without exception possess a Buddha expounded prior to the Lotus Sutra Buddha nature and indicates that they can should be regarded as “expedient means” attain enlightenment in this life, as they are, and set aside. In the Immeasurable Meanings in their present form. Sutra, considered an introduction to the Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni says: “Preaching the Law in various different ways, I made use of the Outline and Structure of power of expedient means. But in these more the Lotus Sutra than forty years, I have not yet revealed the truth” (The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and n analyzing the contents of the Lotus Sutra, Closing Sutras, p. -

OR the BASIC VOW of a BODHISATTVA HAYASHIMA Kyosho

A STUDY IN THE THOUGHT OF 'HNAN' OR THE BASIC VOW OF A BODHISATTVA HAYASHIMA Kyosho I. The thought of the basic vow and the path of religious practice in Buddhism. One of the outstanding features of Mahayana Buddhism lies in its clarification of the religious life of the bodhisattva, the seeker after enlightenment. His religious life consists in the two aspects of benefiting oneself' (seeking after enlightenment for himself) and benefiting others' (imparting the Teaching to others, and aiding them in their quest for enlightenment). As a result, the numerous Buddhas as preached in the Mahayana are those creatures who have thus perfected themselves in this religious life. And the bodhisattva takes as his ideal that Buddha which most closely resembles himself in his practice of the religious life. The bodhisattva first produces the determination or the will to strive after enlightenment, referred to as 'hotsu bodai-shin', or the produc- tion of the mind of 'bodhi' or enlightenment. Next, in order that they may make more concrete their individual bodhisattva-paths, each one of them puts forth a 'hon-gan' or basic vow (miila-pranidhana, purva-pra- nidhana), and then continues his religious practices in accordance with this vow. And it is the unity of this religious. practice and the aim of this vow that constitutes the perfection of the bodhisattva's religious life, and when this takes place the bodhisattva's promise is fulfilled that all other creatures attain to Buddhahood at the very same time. Bodhisattvas put forth vows that are common to all bodhisattvas, as well as their own, individually unique vows. -

Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

issn 0304-1042 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies volume 47, no. 1 2020 articles 1 Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D. McMullen 11 Buddhist Temple Networks in Medieval Japan Daigoji, Mt. Kōya, and the Miwa Lineage Anna Andreeva 43 The Mountain as Mandala Kūkai’s Founding of Mt. Kōya Ethan Bushelle 85 The Doctrinal Origins of Embryology in the Shingon School Kameyama Takahiko 103 “Deviant Teachings” The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism Gaétan Rappo 135 Nenbutsu Orthodoxies in Medieval Japan Aaron P. Proffitt 161 The Making of an Esoteric Deity Sannō Discourse in the Keiran shūyōshū Yeonjoo Park reviews 177 Gaétan Rappo, Rhétoriques de l’hérésie dans le Japon médiéval et moderne. Le moine Monkan (1278–1357) et sa réputation posthume Steven Trenson 183 Anna Andreeva, Assembling Shinto: Buddhist Approaches to Kami Worship in Medieval Japan Or Porath 187 Contributors Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47/1: 1–10 © 2020 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.47.1.2020.1-10 Matthew D. McMullen Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan he term “esoteric Buddhism” (mikkyō 密教) tends to invoke images often considered obscene to a modern audience. Such popular impres- sions may include artworks insinuating copulation between wrathful Tdeities that portend to convey a profound and hidden meaning, or mysterious rites involving sexual symbolism and the summoning of otherworldly powers to execute acts of violence on behalf of a patron. Similar to tantric Buddhism elsewhere in Asia, many of the popular representations of such imagery can be dismissed as modern interpretations and constructs (White 2000, 4–5; Wede- meyer 2013, 18–36). -

Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3

WISDOM ACADEMY Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3 JAY GARFIELD Lessons 6: The Transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet, and the Shentong-Rangtong Debate Reading: The Crystal Mirror of Philosophical Systems "Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism," pages 71-75 "The Nyingma Tradition," pages 77-84 "The Kagyu Tradition," pages 117-124 "The Sakya Tradition," pages 169-175 "The Geluk Tradition," pages 215-225 CrystalMirror_Cover 2 4/7/17 10:28 AM Page 1 buddhism / tibetan THE LIBRARY OF $59.95US TIBETAN CLASSICS t h e l i b r a r y o f t i b e t a n c l a s s i c s T C! N (1737–1802) was L T C is a among the most cosmopolitan and prolific Tspecial series being developed by e Insti- Tibetan Buddhist masters of the late eighteenth C M P S, by Thuken Losang the crystal tute of Tibetan Classics to make key classical century. Hailing from the “melting pot” Tibetan Chökyi Nyima (1737–1802), is arguably the widest-ranging account of religious Tibetan texts part of the global literary and intel- T mirror of region of Amdo, he was Mongol by heritage and philosophies ever written in pre-modern Tibet. Like most texts on philosophical systems, lectual heritage. Eventually comprising thirty-two educated in Geluk monasteries. roughout his this work covers the major schools of India, both non-Buddhist and Buddhist, but then philosophical large volumes, the collection will contain over two life, he traveled widely in east and inner Asia, goes on to discuss in detail the entire range of Tibetan traditions as well, with separate hundred distinct texts by more than a hundred of spending significant time in Central Tibet, chapters on the Nyingma, Kadam, Kagyü, Shijé, Sakya, Jonang, Geluk, and Bön schools. -

Buddhism As a Pragmatic Religious Tradition

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Buddhism as a Pragmatic Religious Tradition Our approach to Religion can be called “vernacular” . [It is] concerned with the kinds of data that may, even- tually, be able to give us some substantial insight into how religions have played their part in history, affect- ing people’s ability to respond to environmental crises; to earthquakes, floods, famines, pandemics; as well as to social ills and civil wars. Besides these evils, there are the everyday difficulties and personal disasters we all face from time to time. Religions have played their part in keeping people sane and stable....We thus see religions as an integral part of vernacular history, as a strand woven into lives of individuals, families, social groups, and whole societies. Religions are like technol- ogy in that respect: ever present and influential to peo- ple’s ability to solve life’s problems day by day. Vernon Reynolds and Ralph Tanner, The Social Ecology of Religion The Buddhist faith expresses itself most authentically in the processions of statues through towns, the noc- turnal illuminations in the streets and countryside. It is on such occasions that communion between the reli- gious and laity takes place . without which the religion could be no more than an exercise of recluse monks. Jacques Gernet, Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries 1 2 Popular Buddhist Texts from Nepal Whosoever maintains that it is karma that injures beings, and besides it there is no other reason for pain, his proposition is false.... Milindapañha IV.I.62 Health, good luck, peace, and progeny have been the near- universal wishes of humanity. -

The Popular Teachings of Tendai Ascetics

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Comparative Religion Publications Comparative Religion 2004 Learning to Persevere: The Popular Teachings of Tendai Ascetics Stephen G. Covell Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/religion_pubs Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Covell, Stephen G., "Learning to Persevere: The Popular Teachings of Tendai Ascetics" (2004). Comparative Religion Publications. 4. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/religion_pubs/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Comparative Religion at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Religion Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 31/2: 255-287 © 2004 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Stephen G. Covell Learning to Persevere The Popular Teachings of Tendai Ascetics This paper introduces the teachings of three contemporary practitioners of Tendai Buddhism. I argue that the study of Japanese Buddhism has focused on doctrine and the past to the detriment of our understanding of contempo rary teaching. Through an examination of the teachings of contemporary practitioners of austerities, I show that practice is drawn on as a source more than classical doctrine, that conservative values are prized, and that the teach ings show strong similarities to the teachings of the new religions, suggesting a broad-based shared worldview. k e y w o r d s : Tendai - kaihogyo - morals - education - new religions Stephen G. Covell is Assistant Professor in the Department of Comparative Religion, Western Michigan University.