Work and Learning in Micro Car-Repair Enterprises. A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To User This User's Guide Applies for Lifan LF7160,LF7160L1,LF7130A

Manual del Usuario LIFAN520 Preface To User Dear users: Thank you for your interest in Lifan car and had chosen this car. Lifan car is the latest innovated product developed by this company. Please read the User's Guide carefully before using this vehicle product for the first time, it will guide you to use our product more correct and safer. Also, we would like to ask you to take maintenance at your local service station as per stipulation in Maintenance Manual. In time and necessary maintenance will not only prolong service life of the car, but also will bring you a safe journey. Our company is committing in continuous improvement of products, and the revision of the manual may not be kept up with this, therefore if you found your car has some features that is different with the descriptions in this Manual, your car is the final reference please. The changes of the revision will be made without any notice in advance. Preface This User's Guide applies for Lifan LF7160,LF7160L1,LF7130A cars If the explanation to certain function of product is not clear enough in this Manual, or is there anything unclear, please contact your local Lifan vehicle service station for help in operation & maintenance. Lifan vehicle will bring you good luck and we wish you a pleasant journey! Thank you Lifan Auto Mexico Manual del Usuario LIFAN520 Content Keys ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Vehicle door ...................................................................................................................................................... -

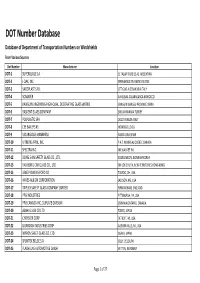

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields from Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields From Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA DOT‐2 J‐DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES DOT‐3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY DOT‐4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO DOT‐5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH‐QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA DOT‐6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY DOT‐7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY DOT‐8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA DOT‐9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN DOT‐10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA DOT‐11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI DOT‐12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA DOT‐13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG DOT‐15 LIBBEY‐OWENS‐FORD CO TOLEDO, OH, USA DOT‐16 HAYES‐ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON, MS, USA DOT‐17 TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND DOT‐18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH, PA, USA DOT‐19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA,ONTARIO, CANADA DOT‐20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO, JAPAN DOT‐21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS, MI, USA DOT‐23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA, JAPAN DOT‐24 SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY, BELGIUM DOT‐25 FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN, GERMANY Page 1 of 27 Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING, NY, USA DOT‐27 SEKURIT SAINT‐GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY DOT‐32 GLACERIES REUNIES S.A. BELGIUM DOT‐33 LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐35 PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER, OH, USA DOT‐36 SOCIETA ITALIANA VETRO S.P.A. -

Double Nickel Chevy

Double Nickel Chevy 139 Townes Grocery Rd. Athens, GA 30605 (706) 548-6194 55-56-57 CHEVY PARTS January Sale 2012 55-57 NEW! DakotaDigital VHX series analog gauges, blue or red illumination, #301FV & GV $795.00 55 NEW! Smoothie 55 front bumper, finally in stock, with mounting brackets #1004E $539.00 55-57 NEW! SmBlk Stainless headers, ¾ length, fits w/aftermarket PS & side mnts #1432FSS $349.00 55-57 Custom Autosound Radios now available!! USA1, 230, 630, DIN, CD Changers, etc Best Prices!! 55 NEW!Sedan Full OEM Quarter Panels (sold each) List $839.00 $739.00 While they last! 56 Hood Bar (tiny flaw-WE CAN’T FIND IT!-very nice!) #461S------ List $209.95 $169.00 56 Lower Grille Bar STAINLESS STEEL finally available!!! #479AS List $329.95 $259.00 57 Grille bar (tiny flaw-WE CAN’T FIND IT!-very nice!) #966S---------- List $309.95 $269.00 57 Hood Bar (tiny flaw-WE CAN’T FIND IT!-very nice!) #474S----------- List $209.95 $169.00 57 NEW! ’FULL’ Quarter Panel--(O.E.M.) 57 HT, specify LH/RH NEW PART! $799.00 55-56 Instrument Cluster Bezels (4pc Set) #2050 & #2051 Reg $379.00 $369.00 55-57 Full Trunk Floor, assembled, with braces Special price! $698.00 55-57 Sedan full Door, #1372J&K, LH or RH Reg. $789.00 $749.00 55-57 Full length ½ floor, without braces #237E&F (EACH SIDE) Reg. $319.00 $295.00 55-57 Full floor assembled w/ braces #237G, #237H & #237i Special price! $1099.00 55-57 Full inner quarter panels with trunk sidewall NEW PART!!! $699.00 55-57 Trunk Lid Assembly complete part #317M&N Reg. -

Nye County Agenda Information Form

NYE COUNTY AGENDA INFORMATION FORM ES1 Action Presentation Presentation & Action Department: Finance Agenda Date: Category: Consent Agenda Item March 15, 2011 Contact: Pam Webster Phone: 775-751-4269 Continued from meeting of: Return to: Location: Phone: Action requested: Approval of cost for Kustom Kolors to perform the extraordinary repairs needed to return a Sheriffs Office vehicle to service in the estimated total amount of $3,250.50 which can be funded from Fund 493 Capital Projects Endowment. Complete description of requested action: It is necessary to repair damages suffered from gunshots to NCSO vehicle #1 D7HU 1 8205J2 15891. As this qualifies as extraordinary maintenance cost, it is permissible to use Capital Projects funds to cover the cost as per Nye county Ordinance 326, section 3.28.050 (B). The cost of these repairs is estimated at $3,250.50 according to the attached backup material. Any information provided after the agenda is published or during the meeting of the Commissioners will require you to provide 20 copies: one for each Commissioner, one for the Clerk, one for the District Attorney, one for the Public and two for the County Manager. Contracts or documents requiring signature must be submitted with three original copies. Expenditure Impact by FY(s): (Provide detail on Financial Form) 1E1 No fmancial impact Routing & Approval (Sign & Date) 1. Dept Date 6. Date 2. Date 7. HR Date Date Date 3• 8. Legal 4. Date 9. Finance Date Date 5. Hi County Manager f Jafiace on Agenda V __________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________ AGENDA FINANCIAL FORM Agenda Item No.: 1. -

New IDEAS for Transit

IDEA Innovations Deserving Exploratory Analysis Programs TRANSIT New IDEAS for Transit Transit IDEA Program Annual Report DECEMBER 2020 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2020 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2020 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* OFFICERS CHAIR: Carlos M. Braceras, Executive Director, Utah Department of Transportation, Salt Lake City VICE CHAIR: Susan A. Shaheen, Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering and Co-Director, Transportation Sustainability Research Center, University of California, Berkeley EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Neil J. Pedersen, Transportation Research Board MEMBERS Michael F. Ableson, CEO, Arrival Automotive–North America, Birmingham, MI Marie Therese Dominguez, Commissioner, New York State Department of Transportation, Albany Ginger Evans, CEO, Reach Airports, LLC, Arlington, VA Nuria I. Fernandez, General Manager/CEO, Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, San Jose, CA Nathaniel P. Ford, Sr., Chief Executive Officer, Jacksonville Transportation Authority, Jacksonville, FL Michael F. Goodchild, Professor Emeritus, Department of Geography, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA Diane Gutierrez-Scaccetti, Commissioner, New Jersey Department of Transportation, Trenton Susan Hanson, Distinguished University Professor Emerita, Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, MA Stephen W. Hargarten, Professor, Emergency Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Chris T. Hendrickson, Hamerschlag University Professor of Engineering Emeritus, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, -

New IDEAS for Transit

IDEA Innovations Deserving Exploratory Analysis Programs TRANSIT New IDEAS for Transit Transit IDEA Program Annual Report DECEMBER 2019 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2019 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* OFFICERS CHAIR: Victoria A. Arroyo, Executive Director, Georgetown Climate Center; Assistant Dean, Centers and Institutes; and Professor and Director, Environmental Law Program, Georgetown University Law Center, Washington, D.C. VICE CHAIR: Carlos M. Braceras, Executive Director, Utah Department of Transportation, Salt Lake City EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Neil J. Pedersen, Transportation Research Board MEMBERS Michael F. Ableson, CEO, Arrival Automotive–North America, Detroit, MI Ginger Evans, CEO, Reach Airports, Arlington, VA Nuria I. Fernandez, General Manager/CEO, Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, San Jose, CA Nathaniel P. Ford, Sr., Executive Director–CEO, Jacksonville Transportation Authority, Jacksonville, FL A. Stewart Fotheringham, Professor, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, Arizona State University, Tempe Diane Gutierrez-Scaccetti, Commissioner, New Jersey Department of Transportation, Trenton Susan Hanson, Distinguished University Professor Emerita, Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, MA Stephen W. Hargarten, Professor, Emergency Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Chris T. Hendrickson, Hamerschlag University Professor of Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA S. Jack Hu, Vice President for Research and J. Reid and Polly Anderson Professor of Manufacturing, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Roger B. Huff, President, HGLC, LLC, Farmington Hills, MI Ashby Johnson, Executive Director, Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (CAMPO), Austin, TX Geraldine Knatz, Professor, Sol Price School of Public Policy, Viterbi School of Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles William Kruger, Vice President, UPS Freight for Fleet Maintenance and Engineering, Richmond, VA Julie Lorenz, Secretary, Kansas Department of Transportation, Topeka Michael R. -

Brick 10005234: Antifreeze/Coolants (Automotive)

Brick 10005234: Antifreeze/Coolants (Automotive) Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as a liquid preparation added to the water of a vehicle to lower its freezing point or to increase the boiling point. Excludes antifreezes not specifically intended for automotive use. If Condensed (20000095) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify whether or not the product is condensed Attribute Values NO (30002960) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) YES (30002654) If Ready to Use (20002281) Attribute Definition Indicate, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify whether the product is in a state or form that requires no further manipulation or addition of another substance prior to usage. Attribute Values NO (30002960) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) YES (30002654) Type of Antifreeze/Coolant (20002274) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify the type of antifreeze/coolant. Attribute Values DIETHYLENE GLYCOL ETHYLENE GLYCOL PROPYLENE GLYCOL UNCLASSIFIED (30002515) (30011941) (30011922) (30011921) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) Page 1 of 298 Page 2 of 298 Brick 10003009: Anti-theft Products Other Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as an anti–theft product designed to prevent a car theft, where the user of the schema is not able to classify the products in existing bricks within the schema. Excludes all currently classified Anti–Theft Car Products. Page 3 of 298 Brick 10005129: Anti-theft Products Replacement Parts/Accessories Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as replacement parts or accessories for Anti–theft products. -

DOT No. MANUFACTURER NAME CITY STATE COUNTRY 1 SUPERGLASS S.A

DOT No. MANUFACTURER NAME CITY STATE COUNTRY 1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA 2 J-DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES 3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY 4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO 5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH-QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA 6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY 7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY 8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA 9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN 10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA 11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI 12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA 13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG 14 WITHDRAWN - SEE COMMENTS 15 LIBBEY-OWENS-FORD CO TOLEDO OHIO UNITED STATES 16 HAYES-ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON MISSISSIPPI UNITED STATES 17 PILKINGTON AUTOMOTIVE (UK) LTD. BIRMINGHAM ENGLAND 18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH PENNSYLVANIA UNITED STATES 19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA ONTARIO CANADA 20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO JAPAN 21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT MICHIGAN UNITED STATES 22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS MICHIGAN UNITED STATES 23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA JAPAN 24 AGC AUTOMOTIVE EUROPE SA GILLY BELGIUM 25 PILKINGTON AUTOMOTIVE DEUTSCHLAND GMBH WITTEN GERMANY 26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING NEW YORK UNITED STATES 27 SAINT-GOBAIN SEKURIT-DEUTSCHLAND GMBH CO. KG AACHEN GERMANY 28 WITHDRAWN - SEE COMMENTS 29 WITHDRAWN - SEE COMMENTS 30 WITHDRAWN - SEE COMMENTS 31 WITHDRAWN - SEE COMMENTS 32 SAINT-GOBAIN SEKURIT BENELUX S.A. SAMBREVILLE BELGIUM 33 LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT MICHIGAN UNITED STATES 34 WITHDRAWN - SEE COMMENTS 35 PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER OHIO UNITED STATES 36 PILKINGTON SIV S.P.A., ITALY SAN SALVO (CHIETI) ITALY 37 SAINT-GOBAIN SEKURIT ITALIA S.R.L. -

Workshop Solutions Ideas

LIQUI MOLY GmbH Jerg-Wieland-Straße 4 89081 Ulm GERMANY Phone: +49 731 1420-0 Fax: +49 731 1420-75 E-Mail: [email protected] www.liqui-moly.com Technical Support: Phone: +49 731 1420-871 E-Mail: [email protected] No liability for misprints. Subject to technical modifications. Free of charge! The LIQUI MOLY app. liqui-moly.to/AppStore liqui-moly.to/PlayStore With best regards: Workshop solutions Ideas. Solutions. Success. 52842008 CONTENTS NOTES NOTES SELLING OIL 4 CONTENTS Oil marketing: enhance with sales aids and expert knowledge. OIL ACCESSORIES 5 LIQUI MOLY has everything needed for safe and orderly oil storage and dispensing. STORAGE SOLUTIONS 10 Orderly and secure: the oil cabinets for all LIQUI MOLY lubricants. EARNING MONEY WITH ADDITIVES 14 Solve engine problems and earn money – with LIQUI MOLY additives. SHOP DISPLAYS 25 Attractive and space-saving displays ensure greater turnover in your sales room. GEAR TRONIC 27 Change automatic transmission fluid simple and fast. CAR GLASS INSTALLATION 33 Additional business from bonding glass screens and plastic repairs. LAMINATED GLASS REPAIR 35 Professional and economical repairs of glass damage. ASD FILLING STATION 38 The clever air spray system with refillable spray cans. AIR-CONDITIONING SYSTEM CLEANER 40 Workshop utilization and satisfied customers. 2 LIQUI MOLY 2020 LIQUI MOLY 2020 67 CONTENTS TORNADOR GUN 42 CONTENTS A clean business to boost your turnover. INTERNET 44 Everything firsthand – via a direct line to LIQUI MOLY. TEAM SHOP 47 Order company, leisure and work clothing economically. SALES PROMOTION 49 Decorate your business with the appeal of a well-known brand. -

Not Just Another Windscreen Tool 3

AUTO GLASS TOOLS & ACCESSORIES AUTO EDITION 2020/2021 Cut-Out Technology Preparation Installation Specialty Tools Repair Protection & Care Cord & Wire Cut-Out Technology 5 1 Pull Knife Cut-Out Technology 33 2 Power Tools (electric & pneumatic) 45 3 Dismantling & Installation Tools 73 4 Scrapers & Miscellaneous Cutting Tools 95 5 Sensor Technology 109 6 Auto Glass Installation 125 7 Adhesive, Tapes & Rubber Profiles 157 8 Tools for Rubber Moulded Glass 181 9 Auxiliary Hand Tools 187 10 Toolkits & Storage Systems 199 11 Transportation & Storage of Glass 215 12 Windscreen Repair & Scratch Removal 227 13 Headlight Restoration 265 14 Vehicle Protection & Personal Protective Equipment 271 15 Cleaning, Maintaining & Coating 283 16 www.proglass.de 3 IMPRINT Editor ProGlass GmbH Michael-Becker-Strasse 2 73235 Weilheim Germany Phone: +49 (0) 7023 / 90013-0 Fax: +49 (0) 7023 / 90013-23 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.proglass.de VAT Reg. No.: DE 813 343 270 Managing Director: Oliver Siegler Registered at local court Stuttgart, HRB 231787 Copyright Note This catalogue is copyrighted.Re- production of any part in any way is prohibited without the exclu- sive written consent of ProGlass GmbH. Trademarks The name ProGlass and the Pro- Glass logo is a trademark by Oliver Siegler in favour of ProGlass GmbH. Other product or company names in this catalogue are trademarks of the relative companies. Errors and technical changes excepted! Date of Issue: June 2020 1 Cord & Wire Cut-Out Technology Cord & Wire Cut-Out 1 Cord & Wire Cut-Out Technology 5 G G G OUTSIDE VIEW OUTSIDE OUTSIDE VIEW OUTSIDE E OUTSIDE VIEW OUTSIDE E E A B A B A B C C C B B B D D A D A A 3. -

Exclusive Carcare

® PERFECT VEHICLE SERVICE CARCARE CAR SHIPPING Take advantage of our expert services (page 5) Car Care Car Glass Smart Repair EXCLUSIVE WE ACCEPT DOLLARS (daily exchange rate for all quotations) INTERNAL CLEANING Don‘t forget your VAT form - you‘ll save incredible 19% (German VAT) Basis internal cleaning • thorough vacuum cleaning of interior and trunk • intensive dashboard, center console cleaning, care and sealing of the whole interior • cleaning windows (inside) A B C D small car mid-size-car large car SUV / Van from from from from 44.- € 49.- € 57.- € 67.- € Not sure which category your car belongs to? Please refer to page 3. Professional internal cleaning • thorough vacuum cleaning of interior and trunk • intensive dashboard, center console cleaning, care and sealing of the whole interior • cleaning windows (inside) • high-value cushion shampooing • leather purifi cation with special care products • superb leather care with carnauba wax • carpet shampooing A B C D small car mid-size-car large car SUV / Van from from from from 84.- € 89.- € 99.- € 109.- € Not sure which category your car belongs to? Please refer to page 3. Phone +49 (0)9602 9442866 eMail [email protected] Prices are valid after 2014/03/01. Prices include 19% German VAT. Please do not forget to bring your VAT form to save 19% German VAT. Otherwise all prices like mentioned. Prices are valid for cars with normal stains. Subject to modifi cations and errors excepted. Call us for any further question and information. 2 EXTERNAL CLEANING Don‘t forget your VAT form - you‘ll save incredible 19% (German VAT) Basic external care • quality hand wash with rim cleaning 2 polishing • cleaning door jam, A-, B- and C-pillar steps • removal of surface rust and tar spots • high-gloss polishing and special paint sealant • sealing of all exterior synthetics A B C D small car mid-size-car large car SUV / Van from from from from 74.- € 84.- € 94.- € 104.- € Not sure which category your car belongs to? Please see below. -

Alien Motor Speedway

Alien Motor Speedway October 30-31, 2020 Demolition Derby Safety Rules and Regulations ALL CARS MUST BE AT THE TRACK BY 5PM ON 10-30-2020 FOR INSPECTION, DRIVERS MEETING, AND HEAT DRAWS. STOCK DERBY CAR (NO convertibles, Ambulances, circuit cars will be allowed.) with NO modifications other than the following; 1) Any arguments and/or violations can result in disqualification and ejection from ALIEN MOTOR SPEEDWAY Cars must pass a pre-inspection prior to entering the pit area. All inspections are the responsibility of the pit officials. Only the driver and mechanics will be allowed at the inspection/check in. All decisions made by officials are final. You must be a driver to protest, the fee is $200 and you must have cash in hand. This protest must take place immediately at the conclusion of the feature event. 2) Stock gas tanks must be removed. Auxiliary fuel tanks will be placed in the middle of the back-seating area and must be secured with metal straps or bolted threw the floor board with backing plate no bigger than ¼ inch thick 6x6, may not be used to strengthen the car. All tanks must be legal racing design and vented with a maximum 5 gallons of pump gasoline. Fuel lines are to be routed under the car and are not permitted inside the driver’s compartment. Electric fuel pumps may be 1 used but must have an emergency cut off switch located on passenger side pillar, Switch and pillar must be painted orange, 3) All car glass, aluminum, plastic, chrome, pot metal, door handles, key locks, dash plastics, heater core suitcases, or any hazardous pieces and loose debris must be removed from the car.