Calvinist Thomism Revisited: William Ames (1576–1633) and the Divine Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rehabilitation of Scholasticism? a Review Article on Richard A. Muller's Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, Vol

A REHABILITATION OF SCHOLASTICISM? A REVIEW ARTICLE ON RICHARD A. MULLER'S POST-REFORMATION REFORMED DOGMATICS, VOL. I, PROLEGOMENA TO THEOLOGY* DOUGLAS F. KELLY REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI For decades the idea of scholastic theology has tended to raise very nega tive images, especially among Protestants. The very words 'Protestant scholasticism' or 'seventeenth-century Orthodoxy' conjure up mental pic tures of decaying calf-bound Latin folios covered with thick dust. Of forced and inappropriate proof-texting inside, of abstract and boring syl logisms, far removed from the dynamism of biblical history and concerns of modem life, of harsh logic, a polemical spirit and an almost arrogant propensity to answer questions which the ages have had to leave open. The 'Biblical Theology' movement inspired by Barth and Brunner earlier this century, and the great flowering of sixteenth-century Reformation studies since World War 11 have given seventeenth-century Protestant scholasticism very poor marks when compared with the theology of the original Reformers. The fresh emphasis on the dynamic development of the theology in tfie Scriptures among Evangelicals (post-V os) and vari ous approaches to the 'New Hermeneutics' among those in the more lib eral camp have raised serious questions about the scriptural balance (if not validity) of the more traditional Protestant text-book theology. R. T. Kendall, for instance, has quite negatively evaluated the seventeenth-cen tury Westminster confessional theology in light of the very Calvin whom the Westminster divines certainly thought they were following. 1 Can anything good, therefore, be said these days about Protestant scholasticism? Is it even legitimate to reopen this subject in a serious way? Richard A. -

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

Anglican Reflections on Justification by Faith

ATR/95:1 Anglican Reflections on Justification by Faith William G. Witt* This article reexamines the Reformation doctrine of justification by faith alone in the light of traditional criticisms and misunder- standings, but also of recent developments such as agreed ecu- menical statements and the “New Perspective” on Paul. Focusing on formulations of justification found in Anglican reformers such as Thomas Cranmer and Richard Hooker, the author argues that justification by grace through faith is a summary way of saying that salvation from sin is the work of Jesus Christ alone. Union with Christ takes place through faith, and, through this union, Christ’s atoning work has two dimensions: forgiveness of sins (jus- tification) and transformation (sanctification). Union with Christ is sacramentally mediated (through baptism and the eucharist), and has corporate and ecclesial implications, as union with Christ is also union with Christ’s body, the church. The Reformation doctrine of justification by faith is much misun- derstood. Among Roman Catholics, there is the caricature of justifica- tion by faith as a “legal fiction,” as if there were no such thing as a Protestant theology of either creation or sanctification. Similar to the accusation of “legal fiction” was the older criticism that justification by faith was an example of the tendency of late medieval Nominalism to reduce salvation to a matter of a divine voluntarist command, with no correlation to any notion of inherent goodness. For Luther, it was said, the Nominalist God could declare to be righteous someone who * William G. Witt is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology at Trinity School for Ministry, where he teaches both Systematic Theology and Ethics. -

Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2020 Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789 Stephen Michael Wolfe Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wolfe, Stephen Michael, "Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5344. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5344 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROTESTANT EXPERIENCE AND CONTINUITY OF POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EARLY AMERICA, 1630-1789 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Stephen Michael Wolfe B.S., United States Military Academy (West Point), 2008 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2016, 2018 August 2020 Acknowledgements I owe my interest in politics to my father, who over the years, beginning when I was young, talked with me for countless hours about American politics, usually while driving to one of our outdoor adventures. He has relentlessly inspired, encouraged, and supported me in my various endeavors, from attending West Point to completing graduate school. -

1 the Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas

The Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas: A Conflict over Authority? On 10 December 1520 at the Elster Gate of Wittenberg, Martin Luther burned his copy of the papal bull Exsurge domine, issued by pope Leo X on 15 June of that year, demanding of Luther to retract 41 errors from his writings. The time for Luther to react obediently within 60 days had expired on that date. The book burning was a response to the burning of Luther’s works which his adversary Johannes Eck had staged in a number of cities. Johann Agricola, Luther’s student and president of the Paedagogium of the University, who had organized the event at the Elster Gate, also got hold of a copy of the books of canon law which was similarly committed to the flames. Following contemporary testimonies it is probable that Agricola had also tried to collect copies of works of scholastic theology for the burning, most notably the Summa Theologiae. However, the search proved unsuccessful and the Summa was not burned alongside the papal bull since the Wittenberg theologians – Martin Luther arguably among them – did not want to relinquish their copies.1 The event seems paradigmatic of the attitude of the early Protestant Reformers to the Summa and its author. In Luther’s writings we find relatively frequent references to Thomas Aquinas, although not exact quotations.2 With regard to the person of Thomas Luther could gleefully report on the girth of Thomas Aquinas, including the much-repeated story that he could eat a whole goose in one go and that a hole had to be cut into his table to allow him to sit at the table at all.3 At the same time Luther could also relate several times and in different contexts in his table talks how Thomas at the time of his death experienced such grave spiritual temptations that he could not hold out against the devil until he confounded him by embracing his Bible, saying: “I believe what is written in this book.”4 At least on some occasions Luther 1 Cf. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

DIVINE WILL and HUMAN CHOICE Freedom, Contingency, and Necessity in Early Modern Reformed Thought

DIVINE WILL AND HUMAN CHOICE Freedom, Contingency, and Necessity in Early Modern Reformed Thought RICHARD A. MULLER K Richard A. Muller, Divine Will and Human Choice Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2017. Used by permission. (Unpublished manuscript—copyright protected Baker Publishing Group) © 2017 by Richard A. Muller Published by Baker Academic a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.bakeracademic.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Title: Divine will and human choice : freedom, contingency, and necessity in early modern reformed thought / Richard A. Muller. Description: Grand Rapids : Baker Academic, 2017. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052081 | ISBN 9780801030857 (cloth) Subjects: LCSH: Free will and determinism—Religious aspects—Christianity—History of doctrines. | Reformed Church—Doctrines. Classification: LCC BT810.3 .M85 2017 | DDC 233/.70882842—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052081 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Richard A. Muller, Divine Will and Human Choice Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2017. Used by permission. (Unpublished manuscript—copyright protected Baker Publishing Group) For Ethan, Marlea, and Anneliese Richard A. Muller, Divine Will and Human Choice Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2017. -

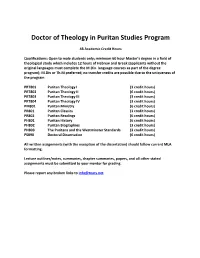

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

Church History, Lesson 11: the Modern Church, Part 1: the Age of Reason and Experience (1648 – 1789)

84 Church History, Lesson 11: The Modern Church, Part 1: The Age of Reason and Experience (1648 – 1789) 33. Reason a. Enlightenment 61 i. Autonomy: no longer was the church or Scripture the basis of authority but reason became the basis of authority. The mentality was: “Let your conscience be your guide.” ii. Rationalism: 1. René Descartes (1596 – 1650) a. He made doubt the fundamental first principle of philosophy. b. You began by doubting everything until you find something not to doubt. c. For Descartes, he could not doubt that he was thinking. d. Thus, he established his own existence. e. The upshot is the starting point of inquiry is no longer God but self (and doubt). 2. John Locke (1632 – 1704) a. Divided religious knowledge into three categories: i. Some religious knowledge that is based on human reason. ii. Some religious knowledge that is above reason and requires faith (e.g., the resurrection). iii. Some religious knowledge is contrary to faith. 61 Adapted from: Frank A. James, “History of Christianity II,” class notes (Reformed Theological Seminary, 2003), 55-60. Church History © 2015 by Dan Burrus 85 b. The Reasonableness of Christianity (1695) suggested that ideas contrary to reason must be rejected. (Revelation cannot contradict reason.) iii. Optimism: scientific revolution 1. Nicholas Copernicus (1473 – 1543): heliocentric theory of the solar system. 2. Francis Bacon (1561 - 1626): developed the Scientific Method (empiricism). 3. Isaac Newton (1642 – 1727): three laws of motion; law of gravity. iv. Superstition 1. Enlightenment thinkers traced the persistence of superstition to Christianity. 2. To rid of superstition, Christianity must be rationalized.