Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Make Yourself At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

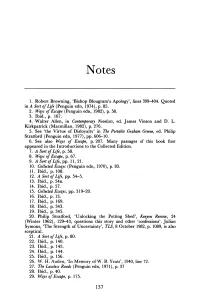

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

The Modern World Through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’S a Burnt-Out Case and the Confidential Agent As Dystopian Novels

Nebula 6.2 , June 2009 The Modern World through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’s A Burnt-out Case and The Confidential Agent as Dystopian Novels. By Ayobami Kehinde What an absurd thing it was to expect happiness in a world so full of misery…. Point me out the happy man and I will point you out either egotisms, evil - or else an absolute ignorance (Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter, 1948: 117) Graham Greene was undoubtedly one of the most gifted and acclaimed novelists of the War/Post-war era in Britain. His novels reflect a constant search for new novelistic modes of expression capable of visualizing the disillusionment and malaise of the modern world. According to Waldo Clarke (1976), an enduring trait of Greene’s fiction is the willingness to look at the repulsive face of the twentieth century. Since literature mostly reflects the mood of its age and enabling contexts, Greene’s fiction dwells on the conflicts and pains of the modern world. The central burden of this discourse is to prove that Greene’s novels steadily progressed in his bold use of the convention of dystopian fiction. It has been proved elsewhere that Greene’s The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter are quintessential existential dystopian novels (See: Ayo Kehinde, 2004). However, in this present paper, an attempt is made to study more closely the dystopian features and political and ideological implications of the deployment of this convention in Greene’s The Confidential Agent and A Burnt-out Case . -

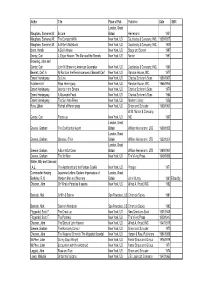

Eng Book2002

Author Title Place of Pub. Publisher Date ISBN London, Great Maugham, Somerset W. Encore Britain Heinemann 1951 Maugham, Somerset W. The Constant Wife New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1926/1927 Maugham, Somerset W. A Writer's Notebook New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1949 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House New York, US Stage and Screen 1997 Gentry, Curt J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets New York, US Norton 1991 Browning, John and Gentry, Curt John M. Browning American Gunmaker New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1964 Bennett, Cerf. A At Random the Reminiscences of Bennett Cerf New York, US Random House, INC. 1977 Ernest Hemingway By Line New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1956/1967 Hotchner A.E. Papa Hemingway New York, US Random House, INC. 1955/1966 Ernest Hemingway Islands in the Stream New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1970 Ernest Hemingway A Moveable Feast New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1964 Ernest Hemingway The Sun Also Rises New York, US Modern Library 1926 Ross, Lillian Portrait of Hemingway New York, US Simon and Schuster 1950/1961 W.W. Norton & Company, Gentry, Curt Frame-up New York, US INC 1967 London, Great Greene, Graham The Confidential Agent Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1939/1952 London, Great Greene, Graham Stamboul Train Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1932/1951 London, Great Greene, Graham A Burnt-Out Case Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1960/1961 Greene, Graham The 3rd Man New York, US The Viking Press 1949/1950 Wilder, Billy and Diamond, I.A.L. The Apartment and the Fortune Cookie New York, US Praeger 1971 Commander Hasting Japanese Letters: Eastern Impressions of London, Great Berkeley, R.N. -

The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene Stephen D. Arata College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arata, Stephen D., "The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625259. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6j1s-0j28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mystery of Evil // in Five Works by Graham Greene A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Stephen D. Arata 1984 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts /;. WiaCe- Author Approved, September 1984 ABSTRACT Graham Greene's works in the 1930s reveal his obsession with the nature and source of evil in the world. The world for Greene is a sad and frightening place, where betrayal, injustice, and cruelty are the norm. His books of the 1930s, culminating in Brighton Rock (1938), are all, on some level, attempts to explain why this is so. -

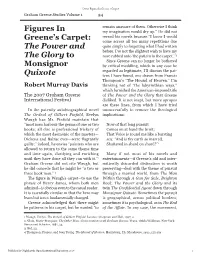

The Power and the Glory to Monsignor Quixote

Davis: Figures In Greene’s Carpet Graham Greene Studies Volume 1 24 remain unaware of them. Otherwise I think Figures In my imagination would dry up.” He did not reread his novels because “I know I would Greene’s Carpet: come across all too many repetitions due The Power and quite simply to forgetting what I had written before. I’ve not the slightest wish to have my The Glory to nose rubbed onto ‘the pattern in the carpet’.”3 Since Greene can no longer be bothered Monsignor by critical meddling, which in any case he regarded as legitimate, I’ll discuss the pat- Quixote tern I have found, one drawn from Francis Thompson’s “The Hound of Heaven.” I’m Robert Murray Davis thinking not of “the labyrinthian ways,” which furnished the American-imposed title The 2007 Graham Greene of The Power and the Glory that Greene International Festival disliked. It is not inapt, but more apropos are these lines, from which I have tried In the patently autobiographical novel unsuccessfully to remove the theological The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, Evelyn implications: Waugh has Mr. Pinfold maintain that “most men harbour the germs of one or two Now of that long pursuit books; all else is professional trickery of Comes on at hand the bruit; which the most daemonic of the masters— That Voice is round me like a bursting Dickens and Balzac even—were flagrantly sea: “And is thy earth so marred, guilty;” indeed, he envies “painters who are Shattered in shard on shard?”4 allowed to return to the same theme time and time again, clarifying and enriching Many if not most of his novels and until they have done all they can with it.”1 entertainments—if Greene’s old and inter- Graham Greene did not cite Waugh, but mittently discarded distinction is worth he did concede that he might be “a two or preserving—deal with the theme of pursuit three book man.” 2 through a marred world, from The Man The figure in Waugh’s carpet—to use the Within through A Gun for Sale, Brighton phrase of Henry James, whom both men Rock, The Power and the Glory and its admired—is obvious even to the casual reader. -

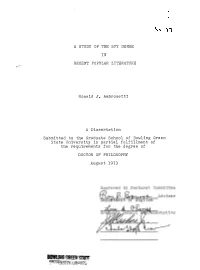

IN Ronald J. Ambrosetti a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School

A STUDY OP THE SPY GENRE IN RECENT POPULAR LITERATURE Ronald J. Ambrosetti A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY August 1973 11 ABSTRACT The literature of espionage has roots which can be traced as far back as tales in the Old Test ament. However, the secret agent and the spy genre remained waiting in the wings of the popular stage until well into the twentieth century before finally attracting a wide audience. This dissertation analyzed the spy genre as it reflected the era of the Cold War. The Damoclean Sword of the mid-twentieth century was truly the bleak vision of a world devastated by nuclear pro liferation. Both Western and Communist "blocs" strove lustily in the pursuit of the ultimate push-button weapons. What passed as a balance of power, which allegedly forged a détente in the hostilities, was in effect a reign of a balance of terror. For every technological advance on one side, the other side countered. And into this complex arena of transis tors and rocket fuels strode the secret agent. Just as the detective was able to calculate the design of a clock-work universe, the spy, armed with the modern gadgetry of espionage and clothed in the accoutrements of the organization man as hero, challenged a world of conflicting organizations, ideologies and technologies. On a microcosmic scale of literary criticism, this study traced the spy genre’s accurate reflection of the macrocosmic pattern of Northrop Frye’s continuum of fictional modes: the initial force of verisimili tude was generated by Eric Ambler’s early realism; the movement toward myth in the technological romance of Ian Fleming; the tragic high-mimesis of John Le Carre' and the subsequent devolution to low-mimesis in the spoof; and the final return to myth in religious affir mation and symbolism. -

ONE HUNDRED BOOKS Blackwell

S rare books ’ ONE HUNDRED BOOKS Blackwell Blackwell’S rare books CATALOGUE B180 Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/ rarebooks Our premises are in the main Blackwell’s bookstore at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest, as well as a large secondhand books department. There is lift access to each floor. The bookstore is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and close to several of the colleges and other university buildings, with on street parking close by. Oxford is at the centre of an excellent road and rail network, close to the London - Birmingham (M40) motorway and is served by a frequent train service from London (Paddington). Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Purchases: We are always keen to purchase books, whether single works or in quantity, and will be pleased to make arrangements to view them. Auction commissions: We attend a number of auction sales and will be happy to execute commissions on your behalf. Blackwell’s online bookshop www.blackwell.co.uk Our extensive online catalogue of new books caters for every speciality, with the latest releases and editor’s recommendations. We have something for everyone. Select from our subject areas, reviews, highlights, promotions and more.