CITY UNIVERSITY of LONDON Robots in the Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

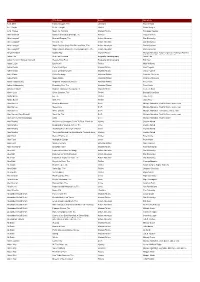

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Issue 53 • July 2013

ISSUE 53 • JULY 2013 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 2 Welcome to Big Finish! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio drama and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. We publish a growing number of books (non-fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. You can access a video guide to the site by clicking here. Subscribers get more at bigfinish.com! If you subscribe, depending on the range you subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a bonus release and discounts. www.bigfinish.com @bigfinish /thebigfinish VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 3 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 4 EDITORIAL Sometimes, I wonder if there’s too much Doctor Who in my ISSUE 53 • JULY 2013 life. My walk to the train station in the morning is twenty-five minutes, give or take. It’s annoying that I have to traipse all the way down to West Croydon (trains to the station nearest the BF office only run at certain, less convenient, times from the nearer SNEAK PREVIEWS East Croydon), but that walk is about the length of a Doctor Who AND WHISPERS episode, so before I even arrive at work, I’m in a Who-ey frame of mind. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC. -

July Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 JUL 2013 JULY COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 6/6/2013 10:07:33 AM Customizable Name tag!t Available only ARMY OF DARKNESS: from your local “S-MART WORK SHIRT” T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! DOCTOR WHO: THE WALKING DEAD: “IT SEEMS TO ME” DEADPOOL: FLOOR POOL “I GOT THIS” T-SHIRT HEATHER T-SHIRT PX WHITE T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now 7 July 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 6/6/2013 9:46:06 AM The STar WarS #1 (of 8) SeX CrimiNaLS #1 Dark horSe ComiCS image ComiCS faireST iN aLL The LaND hC DC ComiCS / VerTigo kiSS me, SaTaN #1 (of 5) raT QueeNS #1 Dark horSe ComiCS image ComiCS PoWerPuff girLS #1 (of 5) iDW PubLiShiNg foreVer eViL #1 Thor: goD of ThuNDer DC ComiCS #13 marVeL ComiCS Jul13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 6/6/2013 2:52:27 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS COW BOY VOLUME 2: UNCONQUERABLE GN l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC AFTERLIFE WITH ARCHIE #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS GOD IS DEAD #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC THE SIMPSONS’ TREEHOUSE OF HORROR #19 l BONGO COMICS 1 SONS OF ANARCHY #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS RASL COMPLETE HC l CARTOON BOOKS KINGS WATCH #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 CODENAME: ACTION #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT THE ART OF SEAN PHILLIPS HC l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT CO-MIX RETROSPECTIVE SPIEGELMAN HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY BOXERS GN l :01 FIRST SECOND SAINTS GN l :01 FIRST SECOND SAILOR MOON: SHORT STORIES VOLUME 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS WORLD OF WARCRAFT TRIBUTE SC l UDON ENTERTAINMENT -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Dead Ringers Was Hastily Composed to Fill in the Gap And, Fortunately, Enough Time Remained Following the Filming Ofthe Shattered Clocks and Yesterday’S Avatar

SUNDAY TV 19 October SERIAL 9J The new co-producers of Doctor Who must have felt themselves baptised by fire, for on their first day on the job, the story that should have filled the third position of the season,Andromeda Sunset, collapsed, and a replacement was needed. Dead Ringers was hastily composed to fill in the gap and, fortunately, enough time remained following the filming ofThe Shattered Clocks and Yesterday’s Avatar. The writing team of Edward Chan and Brad Connors were commissioned for this story, but the names were obvious pseudonyms. Some speculated that Josh Whedon and David Greenbelt had “pulled a City of Death”. The cast and crew flew to Minneapolis for four weeks in June to produce this eight-part (traditional measurement) tale. Upon the debut, controversy erupted, with some complaining about the heightened level of violence, combined with the humorous approach of the story. Some felt the effect wasn’t something the show should emulate. Part one debuted on Sunday, October 19 with 9.7 million view- ers, good for 28th place. Dead Ringers was partially rewritten, with scenes taken from the aborted BBC Books submission The Dead of Winter. VERA STRONG With friends like these… Ryan finds himself in double trouble Doctor Who, BBC1 7.30pm 7.00pm Mighty Mor- LETTERS phin Flower Arrangers The Shattered Clocks was an In The Grass is Always Greener unsatisfying conclusion to the The Arrangers find themselves trilogy begun in Twilight’s Last at the mercy of giant radioactive Gleaming. It feels like nothing more than a lot of running around, crabgrass. -

Low-Resolution Bandwidth-Friendly

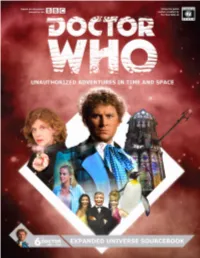

The Sixth Doctor Expanded Universe Sourcebook is a not-for-sale, not-for-profit, unofficial and unapproved fan-made production First edition published August 2018 Full credits at the back Doctor Who: Adventures in Time and Space RPG and Cubicle 7 logo copyright Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd. 2013 BBC, DOCTOR WHO, TARDIS and DALEKS are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation All material belongs to its authors (BBC, Virgin, Big Finish, etc.) No attack on such copyrights are intended, nor should be perceived. Please seek out the original source material, you’ll be glad you did. And look for more Doctor Who Expanded Universe Sourcebooks at www.siskoid.com/ExpandedWho including versions of this sourcebook in both low (bandwidth-friendly) and high (print-quality) formats Introduction 4 Prince Most-Deepest-All-Yellow A66 Chapter 1: Sixth Doctor’s Expanded Timeline 5 Professor Pierre Aronnax A67 Professor Rummas A68 Chapter 2: Companions and Allies Rob Roy MacGregor A69 Angela Jennings A1 Rossiter A70 Charlotte Pollard A2 Salim Jahangir A71 Colonel Emily Chaudhry A3 Samuel Belfrage A72 Constance Clarke A4 Sebastian Malvern A73 Dr Peri Brown A5 Sir Walter Raleigh A74 Evelyn Smythe A6 Tegoya Azzuron A75 Flip Jackson A7 The Temporal Powers A76 Frobisher A8 Toby the Sapient Pig A77 Grant Markham A9 Trey Korte A79 Jamie McCrimmon A10 Winston Churchill A80 Jason and Crystal (and Zog) A11 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart A81 Lieutenant Will Hoffman A13 Mathew Sharpe A14 Chapter 3: Monsters and Villains Melaphyre, The Technomancer A15 Adolf Hitler V1 -

Fish Fingers and Custard Issue 2 Where Do You Go When All the Love Has Gone?

Fish Fingers and Custard Issue 2 Where Do You Go When All The Love Has Gone? Those are lyrics that I have just made up. I’m sure you’ll agree that I’m up there with all the modern musical geniuses, such as Prince, Stevie Wonder, Eric Clapton and Justin Bieber. But where am I going with this? I have an idea and it WILL make sense. Or so I hope… The beauty with Doctor Who is that even when the 13 weeks worth of episodes have gone, we don’t need to cry and mourn for its disappearance (or in my case – ran off without a word and never contacted me again). There are all sorts of commodities out there that we can lay our hands on and enjoy. (I’m starting to regret making this analogy now, as the drug-crazed aliens from Torchwood: Children of Earth would have been a better comparison!) The sheer size of Doctor Who fandom is incredibly huge and you’ll always be able to pick up something that’ll make you feel the way you do when you’re stuck in the middle of an episode. (This fanzine is akin to Love and Monsters than Empty Child/The Doctor Dances, to be honest!) Whether it be a magazine, book, DVD, audiobook, toy (they ARE toys btw), convention, podcast or even a fanzine, it’s all out there for us to explore and enjoy when a series ends, so we’ve no need to get upset and pine until Christmas! And wasn’t Series 5 (or whatever you want to call it) just superb? I can be quite smug here and say that I was never worried about Matt Smith nailing the role of The Doctor. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

History, Power and Monstrosity from Shakespeare to the Fin De Siecle

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses History, power and monstrosity from Shakespeare to the fin de siecle. Roberts, Evan David How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Roberts, Evan David (2007) History, power and monstrosity from Shakespeare to the fin de siecle.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43132 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ History, Power and Monstrosity from Shakespeare toFin the de Siecle. Candidate Name: Evan David Roberts. Student Number: 155235. Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English University of Wales Swansea 2006/2007. ProQuest Number: 10821524 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Vector 241 Butler 2005-05 BSFA

BSFA Membership UK Residents: £26 or £18 (unwaged) per year. Please enquire, or see the BSFA web page for overseas rates. Renewals and New Members - Estelle Roberts - 97 Sharp Street, Newland Vector 1 Avenue, Hull, HU5 2AE Email: [email protected] USA Enquiries - Cy Chauvin, 14248 Wilfred Street, Detroit, MI 48213 USA The Critical Journal of the BFSA Contents Other BSFA Publications 3 Editorial : The View from Behind the Sofa Focus: Simon Morden - 13 Egremont Drive, Sherriff by Andrew M. Butler Hill, Gateshead, NE9 5SE 4 The Picaresque in Juliet E McKenna’s Tales of Einarinn Email [email protected] by Michele Fry Matrix 10 A Pussy in Black Leather: Greebo & the Queer Aesthetic Commissioning Editor: Tom Hunter - by Stacie Hanes Email: [email protected] 14 First Impressions Book Reviews edited by Paul N. Billinger News & Features Editor: Claire Weaver - Email: [email protected] Published by the BSFA ©2005 ISSN 0505 0448 All opinions are those of the individual contributors and should not Production Editor: Martin McGrath - 91 Bentley necessarily be taken as the views of the editors or the BSFA Drive, Harlow, Essex CM1 7 9QT Email: [email protected] Cover The British Science Fiction Association, Ltd. A radar image showing the east coast of central Florida, including the Cape Canaveral area. The Indian River, Banana River and the Atlantic Ocean are the three bodies of water from the lower left to the upper right of this false color (monochromed) image. Limited by guarantee. Company No. 921500 Registered address: 1 Long Parts of NASA's John F. -

Spring 2020 Humanizing the Dehumanized

Scientia et Humanitas: A Journal of Student Research Volume 10 2020 Submission guidelines We accept articles from every academic discipline offered by MTSU: the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities. Eligible contributors are all MTSU students and recent graduates, either as independent authors or with a faculty member. Articles should be 10 to 30 typed double-spaced pages and may include revisions of papers presented for classes, conferences, Scholars Week, or the Social Science Symposium. Articles adapted from Honors or M.A. theses are especially encouraged. Papers should include a brief abstract of no more than 250 words stating the purpose, methods, results, and conclusion. For submission guidelines and additional information, e-mail the editor at scientia@mtsu. edu or visit http://libjournals.mtsu.edu/index.php/scientia/index Student Editorial Staff Jenna Campbell Field: Editor in Chief Gabriella Morin: Managing Editor Jameson Baldwin: Section Editor Reviewers Staff Advisory Board Abigail Williams Marsha Powers Benjamin Yost John R. Vile Elizabeth McGhee Philip E. Phillips Isabella Morrissey Editorial Assistant Jacob Castle Eric Hughes Katherine Mills Kelsey Talbott Journal Design and Layout Susan Lyons Pub 0520-9027 mtsu.edu/scientia ISSN 2470-8127 (print) email:[email protected] ISSN 2470-8178 (online) http://libjournals.mtsu.edu/index.php/scientia ii Letter from the Editors This semester has been stressful for us all. Between the tornadoes that devastated our state and the pandemic that has devastated the world, we have all struggled with trying to find the resolve to make it from one day to the next with our sanity intact.