Spring 2020 Humanizing the Dehumanized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

The Representation, Interpretation and Staging of Magic in Renaissance Plays from the Sixteenth Century Onwards

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The representation, interpretation and staging of magic in Renaissance plays from the sixteenth century onwards. A case study of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Macbeth and Cristopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Professor Doctor fulfilment of the requirements for Sandro Jung the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: English-Spanish” by Tine Dekeyser August 2014 Word count: 27334 Dekeyser i Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Doctor Sandro Jung, for granting me the opportunity to continue working on the same topic of my BA-dissertation and for guiding me towards a more profound investigation of magic and the Renaissance society. Also, I want to thank Professor Jung for reading the many versions of this dissertation and for providing a lot of helpful suggestions throughout the year. Secondly, I would like to thank The British Museum for giving me permission to use their highly detailed engravings, without which this dissertation would not exist. Thirdly, I would like to thank my boyfriend and my mother for supporting me, listening to my dilemmas and calming me down when stress got the better of me. Also, I want to thank my boyfriend for helping me track down the movies I needed for my analyses. Dekeyser ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................... -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

1 2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15

2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15, 2019 3:00-3:15 KEYNOTE “The Fandom Hierarchy: Women of Color’s Fight For Visibility In Fandom Spaces” Tai Gooden Women of Color (WoC) have been fervent Doctor Who fans for several decades. However, the fandom often reflects societal hierarchies upheld by White privilege that result in ignoring and diminishing WoC’s opinions, contributions, and legitimate concerns about issues in terms of representation. Additionally, WoC and non-binary (NB) people of color’s voices are not centered as often in journalism, podcasting, and media formats nor convention panels as much as their White counterparts. This noticeable disparity has led to many WoC, even those who are deemed “important” in fandom spaces, to encounter racism, sexism, and, depending on the individual, homophobia and transphobia in a place that is supposed to have open availability to everyone. I can attest to this experience as someone who has a somewhat heightened level of visibility in fandom as a pop culture/entertainment writer who extensively covers Doctor Who. This presentation will examine women of color in the Doctor Who fandom in terms of their interactions with non-POC fans and difficulties obtaining opportunities in media, online, and at conventions. The show’s representation of fandom and the necessity for equity versus equality will also be discussed to craft a better understanding of how to tackle this pervasive issue. Other actionable solutions to encourage intersectionality in the fandom will be discussed including privileged people listening to WoC and non- binary people’s concerns/suggestions, respectfully interacting with them online and in person, recognizing and utilizing their privilege to encourage more inclusivity, standing in solidarity with them on critical issues, and lending their support to WoC creatives. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Horaire Films

DESHORAIRE FILMS FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE FILMS · 25 e ÉDITION 5-25 AOÛT 2021 FESTIVAL EN LIGNE ET EN SALLE www.fantasiafestival.com DISPONIBLE EN LIGNE À TRAVERS LE CANADA Illustration : Donald Caron Ça comprend des films qui vous suivent partout. APPLI HELIX TV Certaines conditions s’appliquent. IPTV-FANTASIA-REQUIN-10.5X14.125-2107 Document: IPTV-FANTASIA-REQUIN-10.5X14.125-2107 Échelle: 25% Format: 10.5 po X 14.125 po DPI final: 100 dpi ÉPREUVE Coordo: Anouk Chollet Bleed: 0.04 po Imprimeur: Safety: 0.3 po 01 COULEUR PAPIER FOND CMYK RGB Couché Retro Enr Montage: 9 juillet PANTONE Mat Jrnl Final: par: VGAUD ACT OF VIOLENCE IN A AGNES #BLUE_WHALE THE 12 DAY TALE OF THE YOUNG JOURNALIST ÉTATS-UNIS | USA Réal/Dir: Mickey Reece RUSSIE | RUSSIA Réal/Dir: Anna Zaytseva MONSTER THAT DIED IN 8 URUGUAY | URUGUAY Réal/Dir: Manuel Lamas PREMIÈRE INTERNATIONALE | INTERNATIONAL PREMIERE PREMIÈRE MONDIALE | WORLD PREMIERE JAPON | JAPAN Réal/Dir: Shunji Iwai PREMIÈRE NORD-AMÉRICAINE | NORTH AMERICAN PREMIERE Avec son style romantique et maximaliste, Un déchirant et anxiogène thriller russe en PREMIÈRE NORD-AMÉRICAINE | NORTH AMERICAN PREMIERE Blanca, une brillante jeune journaliste qui Mickey Reece nous amène dans un couvent Screenlife qui explore un défi sur les médias Le plus récent film de Shunji Iwai est une rédige une thèse sur la violence, ignore qu’un aux prises avec des rumeurs de possession sociaux menant à une vague de suicides. savoureuse tranche de vie pandémique méta tueur psychopathe est sur ses traces. démoniaque. Gut-wrenching dread tears through this tense entremêlant isolement et kaiju! Blanca, a brilliant young journalist who is writing a With his signature romantic maximalism, Mickey Russian Screenlife thriller that explores a grisly Shunji Iwai’s latest is a delightfully meta slice of thesis on violence, is unaware that a psychopathic Reece’s latest draws us into a convent gripped by social media suicide challenge. -

Doctor Who Party

The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Tim Harrison, Sr. as the 4th Doctor and Eric Stein as Captain Jack Harkness Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Sarah Gilbertson as Raffalo (The End of the World) Esther Harrison as Harriet Jones (The Christmas Invasion) Karen Martin as Rose Tyler Jesse Stein as the 10th Doctor Katie Grzebin as Novice Hame (New Earth) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 10th Doctor and Lindsay Harrison as Rose Tyler (Tooth and Claw) JoLynn Graubart as Martha Jones and Matt Graubart as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Andrew Gilbertson as Prof. Yana (Utopia) Kayleigh Bickings as Lady Christina (Planet of the Dead) Joe Harrison as a Whifferdill (taking the form of Joe Harrison) (DWM: Voyager) 4, 9, 10, and everyone’s favorite Canine Computer... A bowl of Adipose... No substitute for a sonic blaster, but the 9th and 10th are fans... HOME 2010 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 1st Doctor Hayley as a Dalek Camryn Bickings as ...Koquillion? (The Rescue) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 5th Doctor Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Esther Harrison as Sarah Jane Smith BJ Johnson as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Sarah Gilbertson as Lucy Saxon (Last of the Time Lords) Katie Grzebin as Jenny (The Doctor’s Daughter) Karen Martin as the Visionary (The End of Time) Eric Stein as the post-regeneration 11th Doctor (The Eleventh Hour) Joe Harrison as the 11th Doctor Lindsay Harrison as Liz 10 (The Beast Below) JoLynn Graubart as Amy Pond and Matt Graubart as Rory the Roman (The Pandorica Opens) HOME 2009 2011 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 2nd Doctor Joe Harrison as Jamie McCrimmon Timothy Harrison, Jr. -

The Pandorica Opens / the Big Bang Sample

The Black Archive #44 THE PANDORICA OPENS / THE BIG BANG SAMPLE By Philip Bates Published June 2020 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © Philip Bates, 2020 Range Editors: Paul Simpson, Philip Purser-Hallard Philip Bates has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. Also available #32: The Romans by Jacob Edwards #33: Horror of Fang Rock by Matthew Guerrieri #34: Battlefield by Philip Purser-Hallard #35: Timelash by Phil Pascoe #36: Listen by Dewi Small #37: Kerblam! by Naomi Jacobs and Thomas L Rodebaugh #38: The Sound of Drums / Last of the Time Lords by James Mortimer #39: The Silurians by Robert Smith? #40: The Underwater Menace by James Cooray Smith #41: Vengeance on Varos by Jonathan Dennis #42: The Rings of Akhaten by William Shaw #43: The Robots of Death by Fiona Moore This book is dedicated to my family and friends – to everyone whose story I’m part of. CONTENTS Overview Synopsis Introduction 1: Balancing the Epic and the Intimate 2: Myths and Fairytales 3: Anomalies 4: When Time Travel Wouldn’t Help 5: The Trouble with Time 6: Endings and Beginnings -

Rich's Notes: 1 Chapter 1 the Ten Doctors: a Graphic Novel by Rich

The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 1 1 Rich's Notes: The 10th (and current) Doctor goes to The Eye of Orion (the Five Doctors) to reflect after the events of The Runaway Bride. He meets up with his previous incarnation, the 9th Doctor and Rose, here exploring the Eye of Orion sometime between the events of Father’s Day and The Empty Child. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 1 2 Rich's Notes: The 9th and 10th Doctors and Rose stumble upon the 7th Doctor and Ace, who we join at some point between Dimensions in Time and The Enemy Within(aka. The Fox Movie) You’ll notice the style of the drawings changing a bit from page to page as I struggle to settle on a realism vs. cartoony feel for this comic. Hopefully it’ll settle soon. And hopefully none of you will give a rat’s bottom. The Ten Doctors: A Graphic Novel by Rich Morris Chapter 1 3 Rich's Notes: The 10th Doctor, in order to keep the peace, attempts to explain the situation to Ace and Rose. Ace, however, has an advantage. She's seen some of the Doctor's previous incarnations in a strange time trap set up by the Rani (The 30th Anniversary special: Dimensions in Time, which blew chunks). The 2nd Doctor arrives, seemingly already understanding the situation, accompanied by Jamie and Zoe. (The 2nd Doctor arrives from some curious timeline not fully explained by the TV series. Presumably his onscreen regeneration was a farce and he was employed by the Time Lords for a time to run missions for them before they finally changed him into the 3rd Doctor. -

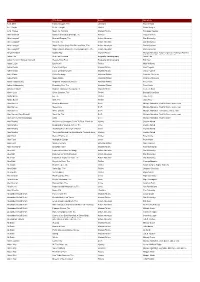

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a.