FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESTORERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS BULLETIN and COMMUNICATIONS OCTOBER 1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Atlas of Musical Instruments

Musik_001-004_GB 15.03.2012 16:33 Uhr Seite 3 (5. Farbe Textschwarz Auszug) The World Atlas of Musical Instruments Illustrations Anton Radevsky Text Bozhidar Abrashev & Vladimir Gadjev Design Krassimira Despotova 8 THE CLASSIFICATION OF INSTRUMENTS THE STUDY OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, their history, evolution, construction, and systematics is the subject of the science of organology. Its subject matter is enormous, covering practically the entire history of humankind and includes all cultural periods and civilizations. The science studies archaeological findings, the collections of ethnography museums, historical, religious and literary sources, paintings, drawings, and sculpture. Organology is indispensable for the development of specialized museum and amateur collections of musical instruments. It is also the science that analyzes the works of the greatest instrument makers and their schools in historical, technological, and aesthetic terms. The classification of instruments used for the creation and performance of music dates back to ancient times. In ancient Greece, for example, they were divided into two main groups: blown and struck. All stringed instruments belonged to the latter group, as the strings were “struck” with fingers or a plectrum. Around the second century B. C., a separate string group was established, and these instruments quickly acquired a leading role. A more detailed classification of the three groups – wind, percussion, and strings – soon became popular. At about the same time in China, instrument classification was based on the principles of the country’s religion and philosophy. Instruments were divided into eight groups depending on the quality of the sound and on the material of which they were made: metal, stone, clay, skin, silk, wood, gourd, and bamboo. -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

Interstellar Music - by Mike Overly

Interstellar Music - by Mike Overly Let's imagine that you could toss a message in a bottle faster than a speeding bullet into the cosmic ocean of outer space. What would you seal inside it for anyone, or anything, to open some day in the distant future, in a galaxy far, far away from our solar system? Well, imagine no more because it's been done! Thirty-five years ago, NASA launched two Voyager spacecraft carrying earthly images and sounds toward the Stars. Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida and Voyager 2 was sent on its way August 20 of that same year. Voyager 1 is now 11 billion miles away from earth and is the most distant of all human-made objects. Everyday, it flies another million miles farther. In fact, Voyager 1 and 2 are so far out in space that their radio signals, traveling at the speed of light, take 16 hours to reach Earth. These radio signals are captured daily by the big dish antennas of the Deep Space Network and arrive at a strength of less than one femtowatt, a millionth of a billionth of a watt. Wow! Both Voyagers are headed towards the outer boundary of the solar system, known as the heliopause. This is the region where the Sun's influence wanes and interstellar space waxes. Also, the heliopause is where the million-mile-per-hour solar winds slow down to about 250,000 miles per hour. The Voyagers have reached these solar winds, also known as termination shock, and should cross the heliopause in another 10 to 20 years. -

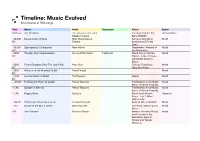

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin

UMS PRESENTS AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN Sunday Afternoon, April 13, 2014 at 4:00 Hill Auditorium • Ann Arbor 66th Performance of the 135th Annual Season 135th Annual Choral Union Series Photo: Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin; photographer: Kristof Fischer. 31 UMS PROGRAM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 Ouverture Courante Gavotte I, II Forlane Menuett I, II Bourrée I, II Passepied I, II Johann Christian Bach (previously attributed to Wilhelm Friedmann Bach) Concerto for Harpsichord, Strings, and Basso Continuo in f minor Allegro di molto Andante Prestissimo Raphael Alpermann, Harpsichord Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach WINTER 2014 Symphony No. 5 for Strings and Basso Continuo in b minor, Wq. 182, H. 661 Allegretto Larghetto Presto INTERMISSION AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE 32 BE PRESENT C.P.E. Bach Concerto for Oboe, Strings, and Basso Continuo in E-flat Major, Wq. 165, H. 468 Allegro Adagio ma non troppo Allegro ma non troppo Xenia Löeffler,Oboe J.C. Bach Symphony in g minor for Strings, Two Oboes, Two Horns, and Basso Continuo, Op. 6, No. 6 Allegro Andante più tosto adagio Allegro molto WINTER 2014 Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of floral art for this evening’s concert. Special thanks to Kipp Cortez for coordinating the pre-concert music on the Charles Baird Carillon. This tour is made possible by the generous support of the Goethe Institut and the Auswärtige Amt (Federal Foreign Office). -

Early Music Performer

EARLY MUSIC PERFORMER JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL EARLY MUSIC ASSOCIATION ISSUE 29 November 2011 I.S.S.N 1477-478X Ruth and Jeremy Burbidge THE PUBLISHERS Ruxbury Publications Scout Bottom Farm Hebden Bridge West Yorkshire HX7 5JS • SANTIAGO DE MURCIA, CIFRAS 2 SELECTAS DE GUITARRA Martyn Hodgson EDITORIAL Andrew Woolley 21 4 MUSIC SUPPLEMENT • FACSIMILES OF SONGS FROM THE / ARTICLES SPINNET: / OR MUSICAL / MISCELLANY • MORROW, MUNROW AND MEDIEVAL (London, 1750) MUSIC: UNDERSTANDING THEIR INFLUENCE AND PRACTICE Edward Breen 24 PUBLICATIONS LIST • DIGITAL ARCHIVES AT THE ROYAL LIBRARY, COPENHAGEN Matthew Hall Peter Hauge COVER: An illustration of p. 44 from the autograph manuscript for J. A. Sheibe’s Passionscantate (1768) (Royal Library, Copenhagen, Gieddes Samling, XI, 11 24). It shows a highly dramatic recitative (‘the curtain is torn and the holy flame penetrates the abominable REPORT darkness’). At first sight the manuscript seems easy to read; however, Scheibe’s notational practice in terms • THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL of accidentals creates problems for the modern CONFERENCE ON HISTORICAL KEYBOARD editor. Scheibe wrote extensively on the function of MUSIC recitative, and especially on the subtle distinction between declamation and recitative. (Peter Hauge) Andrew Woolley 13 REVIEWS • PETER HOLMAN, LIFE AFTER DEATH: THE VIOLA DA GAMBA IN BRITAIN FROM PURCELL TO DOLMETSCH EDITOR: Andrew Woolley [email protected] Nicholas Temperley EDITORIAL BOARD: Peter Holman (Chairman), • GIOVANNI STEFANO CARBONELLI: Clifford Bartlett, Clive Brown, Nancy Hadden, Ian XII SONATE DA CAMARA, VOLS. 1 & 2, ED. Harwood, Christopher Hogwood, David Lasocki, Richard MICHAEL TALBOT Maunder, Christopher Page, Andrew Parrott, Richard Rastall, Michael Talbot, Bryan White Peter Holman ASSISTANT EDITORS: Clive Brown, Richard Rastall EDITORIAL ASSISTANT: Matthew Hall 1 Editorial I am a regular visitor, as I’m sure many readers are, to the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) or the Petrucci Music Library (http://imslp.org.uk). -

Greenwood Organ Company CHARLOTTE

THE DIAPASON AN INTERNATIONAL MONTHLY DEVOTED TO THE ORGAN, THE HARPSICHORD AND CHURCH MUSIC OCTOBER, 1976 J.fferson Avenue Presbyterian Church, CHOIR Detroit. Michi9an. Built by Ernest M. Gamba 1£' &1 pipes S~inn.r, 1925 loriqinal specification puba E. M. Skinner Restored in Detroit Diapason B' &1 pipes II.h.d In THE DIAPASON, M.y 1924, p. Concert Flute S' &I pipes I J: d.dicated May 3, 1926 .....m.nu.1s and kleintl EneMer II S' 122 pipet ped.I, " tanh, .lectro-pnMlmattc: action. Flute 4' &1 pipet Hand-cerved cases from Ob.rammerqau, Nazard 2-2/1' &1 pipes Germanv. R.stor.tion carried out by K.n~ Piccolo 2' &1 pipes neth end Dorothy Holden of th. K & 0 Clarinet I' 61 pipes O,gan Service Co., Fernd.I., Michigan. Orchestral Oboe S' &1 pipes Harp S' £1 notes Th. original fonal design has b •• n pre· Celesta 4' 61 notes ,et'led, without any tonel change, or addi Tremolo tions being mad •• Pouchboatds and pri matie, rel •• th.red using natur.1 ... egetabl. tanned I•• th.r; other pneumatics t.-COY SOLO .red with Poly.lon_ Phosphot.bronu con Sleniorphone S' 7J "ipel tects repl.c.d by silver contuh. Pipe GambD 8' 7] pipes work r.p..... d as ".unary. Orl)entd-choir Gamba Celesle I ' 73 pipes director is Rob.rt Hawksley; Dr. Allan A. Ophideide 16' 7] pipes Zaun is pador. Tuba Mirabilis I' 120" wind) 7] pipes GREAT Tuba I' 13 pipes Diapalon 16' 7J pipes French Horn S' 73 pipes Diap.son I S' 7] p,pes En~I ; ,h Horn S' 73 pipet Diapason II S' 73 pipes Tuba Clerio~ .' 7J piPts Claribel Flute 8' 7J pipes Tremolo EneMer S' 7] pipes Octava .' 7J pipes Flute 01' 7J pipes ECH9 Twelfth 2-2/3' 'I pipes OiilpalOn '8' 7l'pipes FiflHnth 2' &1 pipes Chimney Flute S' 7J pipes Ophideide 1&' (Solo) Voir Ce leste II I ' 122.pipes Trombe S' 73 pipes Tubo S' (Solo) Flute .' 73 pipes Tromba S' 13 pipes Clorion .' 7J pipes Vor Humana S' 73· pipes Tubo Clarion .' ISolo) Chimes (Echo) Chimes 25 notes SWEll Tremolo Bourdon 1&' 7J pipes Di tPolson I S' 7J pipes PEDAL Diopason II S' 7) pipes Clorobella S' 73 pipes Oi.!l pasoft 1&' ]2 pipes Ged.d.:t S' 7J piPH Diapason '" (Great) Gllmb. -

Woodwind Family

Woodwind Family What makes an instrument part of the Woodwind Family? • Woodwind instruments are instruments that make sound by blowing air over: • open hole • internal hole • single reeds • double reed • free reeds Some woodwind instruments that have open and internal holes: • Bansuri • Daegeum • Fife • Flute • Hun • Koudi • Native American Flute • Ocarina • Panpipes • Piccolo • Recorder • Xun Some woodwind instruments that have: single reeds free reeds • Clarinet • Hornpipe • Accordion • Octavin • Pibgorn • Harmonica • Saxophone • Zhaleika • Khene • Sho Some woodwind instruments that have double reeds: • Bagpipes • Bassoon • Contrabassoon • Crumhorn • English Horn • Oboe • Piri • Rhaita • Sarrusaphone • Shawm • Taepyeongso • Tromboon • Zurla Assignment: Watch: Mr. Gendreau’s woodwind lesson How a flute is made How bagpipes are made How a bassoon reed is made *Find materials in your house that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) can use to make a woodwind (i.e. water bottle, straw and cup of water, piece of paper, etc). *Find some other materials that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) you can make a different woodwind instrument. *What can you do to change the sound of each? *How does the length of the straw effect the sound it makes? *How does the amount of water effect the sound? When you’re done, click here for your “ticket out the door”. Some optional videos for fun: • Young woman plays music from “Mario” on the Sho • Young boy on saxophone • 9 year old girl plays the flute. -

IJHS Newsletter 07, 2008

NNeewwsslleetttteerr ooff tthhee IInntteerrnnaattiioonnaall JJeeww’’ss HHaarrpp SSoocciieettyy BoardMatters FeatureComment The opening of the Museum in Yakutsk Franz Kumpl An interview with Fred Crane Deirdre Morgan & Michael Wright RegionalNews PictureGallery Images from the opening of the Museum in Yakutsk Franz Kumpl WebWise IJHS website goes ‘live’ AndFinally… Correspondence NoticeBoard Membership August 2008 Spring / Summer Issue 7 Page 1 of 14 August 2008 Issue 7 BoardMatters – From the President Page 2 FeatureComment – The new Khomus Museum in Yakutsk & Interview with Frederick Crane Page 3 RegionalNews Page 5 PictureGallery Page 12 WebWise Page 13 AndFinally… Page 13 NoticeBoard Page 15 To contribute to the newsletter, send your emails to [email protected] or post to: Michael Wright, General Secretary, IJHS Newsletter, 77 Beech Road, Wheatley, Oxon, OX33 1UD, UK Signed articles or news items represent the views of their authors only. Cover photograph & insert courtesy of Franz Kumpl & Michael Wright Editorial BoardMatters NEWS HEADLINES From the president THE NEW KHOMUS MUSEUM OPENS IN Dear friends, YAKUTSK. The Journal of the International Jew‟s Harp Society, IJHS LAUNCHES ITS FIRST WEBSITE. besides this Newsletter, is indispensable to our work FRED CRANE STEPPING DOWN AS JOURNAL and an integral part the paying members get for their EDITOR. yearly membership fee. Given that the Society basically runs on goodwill, it History has shown that the difference between Journal never ceases to amaze me how much we manage to and Newsletter are as follows: achieve. Sometimes it may seem that nothing is The Journal is published ideally once per year in a happening much, but, just like the swan swimming printed version and with the objective of providing (above) majestically along on the water, the legs are paddling opportunities for the publication of scientific Michael Wight, like mad beneath. -

Fellowship of Makers and Restorers of Historical Instruments Bulletin and Communications

FELLOWSHIP OF MAKERS AND RESTORERS OF HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS BULLETIN AND COMMUNICATIONS. JULY 1977 CONTENTS Page Bulletin no. 8. 2 Report on FoMRHI Seminar no. 2. 11 FoMRHI Book News no. 2. 12 List of Members, as at 23rd June 1977 14 Communications 65 On the sizes of Renaissance and baroque viols and violins. E. Segerman 18 / 66 The range of pitch with gut strings of a given length. William B. Samson 19 7 Principal instruments of fourteenth-century Italy and their structural V features. Howard Mayer Brown 20 68 Comments on technical drawings and photographs of musical instruments. R.K.Lee 28 69 On the dangers of becoming an established scholar. Ephraim Segerman 35 3^70 Profile turning of reamer blanks for use in woodwind*. Rod Cameron 38 71 Humidity cycling for stabilization of gut ?nd wood. Djilda Abbott, Ephraim Segerman and David Rolfe 45 72 Review of: The Manufacture of Musical Instruments, translated by Helen Tullberg. Jeremy Montagu 47 73 Review of: The Diagram Group, Musical Instruments of the World, an Illustrated Encyclopedia. Jeremy Montagu £TI 10a Comment on Com. 10 Attitudes to musical instrument conservation and restoration by G. Grant O'Brien. John Barnes 64 39b Comments on comments (Jan '77) on Com. 39. E.S. and D.A. 65 44c Detailed comments on "The World of Medieval and Renaissance Musical Instruments" by Jeremy Montagu, Part I. E.S. 67 58a On Prematurity of Communication. E.S. and D.A. 71 74 Medieval carvings of musical instruments in St. Mary's Church, Shrewsbury. Lawrence Wright 73 Book News. -

The Bandistan Ensemble, Music from Central Asia

Asia Society and CEC Arts Link Present The Bandistan Ensemble, Music From Central Asia Thursday, July 14, 7:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City Bandistan Ensemble Music Leaders: Alibek Kabdurakhmanov, Jakhongir Shukur, Jeremy Thal Kerez Berikova (Kyrgyzstan), viola, kyl-kiyak, komuz, metal and wooden jaw harps Emilbek Ishenbek Uulu (Kyrgyzstan), komuz, kyl-kiyak Alibek Kabdurakhmanov (Uzbekistan), doira, percussion Tokzhan Karatai (Kazakhstan), qyl-qobyz Sanjar Nafikov (Uzbekistan), piano, electric keyboard Aisaana Omorova (Kyrgyzstan), komuz, metal and wooden jaw harps Jakhongir Shukur (Uzbekistan), tanbur Ravshan Tukhtamishev (Uzbekistan), chang, santur Lemara Yakubova (Uzbekistan), violin Askat Zhetigen Uulu (Kyrgyzstan), komuz, metal jaw harp The Bandistan Ensemble is the most recent manifestation of an adventurous two-year project called Playing Together: Sharing Central Asian Musical Heritage, which supports training, artistic exchange, and career enhancement for talented young musicians from Central Asia who are seeking links between their own musical heritage and contemporary languages of art. The ensemble’s creative search is inspired by one of the universal axioms of artistic avant-gardes: that tradition can serve as an invaluable compass for exploring new forms of artistic consciousness and creativity inspired, but not constrained, by the past. Generously supported by the United States Department of State’s Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, Playing Together was established and has been -

2016 Antitrust Year in Review

2016 ANTITRUST YEAR IN REVIEW AUSTIN BEIJING BOSTON BRUSSELS HONG KONG LOS ANGELES NEW YORK PALO ALTO SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO SEATTLE SHANGHAI WASHINGTON, DC WILMINGTON, DE WSGR 2016 Antitrust Year in Review Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Mergers ............................................................................................................................................... 2 U.S. Trends ................................................................................................................................... 2 Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) Act Compliance ............................................................................... 2 Lessons from the Merger Year in Review ................................................................................. 3 Merger Enforcement Under the Trump Administration .............................................................. 4 International Insights ..................................................................................................................... 5 European Union (EU) ............................................................................................................... 5 China....................................................................................................................................... 7 Agency Investigations .........................................................................................................................