ALEXANDER, JOHN DAVID, D.M.A. a Study of the Influence of Texts From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Sunday 2017

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord April 9, 2017 Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord The Commemoration of the Lord’s Entrance into Jerusalem The Solemn Entrance 5:15 PM, 9:00 AM & 6:30 PM 5:15 PM Hosanna Michael Burkhardt Archdiocesan Boy and Girl Choirs Hosanna, blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord, Hosanna! The Procession 11:00 AM Fanfare for Palm Sunday Richard Proulx Cathedral Basilica Choir 1937-2010 Hosanna! Hosanna to the son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna! O King of Israel! Hosanna! Hosanna in the highest. The Greeting, Address, Blessing and Sprinkling of Palm Branches Gospel Matthew 21:1-11 Invitation to begin the Procession Dear brothers and sisters, like the crowds who acclaimed Jesus in Jerusalem, let us go forth in peace. 11:00 AM Pueri Hebraeorum Liber Usualis Cathedral Basilica Choir English translation, sung in Latin The children of the Hebrews, carrying olive branches, went to meet the Lord, crying our and saying: Hosanna in the highest. 2 The Mass Processional All Glory Laud and Honor St. Theodulph Collect 3 Liturgy of the Word Word and Song Page 134 First Reading Isaiah 50:4-7 My face I did not shield from buffets and spitting knowing that I shall not be put to shame. Responsorial Psalm Psalm 22 Christopher Willcock 6:30 PM Owen Alstott Second Reading Philippians 2:6-11 Christ humbled himself. Because of this God greatly exalted him. -

THEATRE VOICES PEDAL • 32 Contra Violone • 16 Ophicleide • 16

THEATRE VOICES CLASSICAL VOICES GREAT PEDAL • 16 English Post Horn French Trompette • 32 Contra Violone Contra Violone • 16 Brass Trumpet (ten c) Trompete • 16 Ophicleide Posaune • 16 Bombarde Tromba • 16 Diaphone Diapason • 16 Diaphone Diapason • 16 Violone Violone • 16 Solo Tibia Clausa (ten c) Bourdon • 16 Bourdon Bourdon • 16 Tibia Clausa (ten c) Gedackt • 8 English Post Horn French Trompette • 16 Clarinet Cromorne • 8 Trumpet Tromba • 16 Krumet (ten c) Krumet • 8 Open Diapason Octave • 16 Orchestral Oboe (ten c) Basson • 8 Solo Tibia Clausa Gedackt • 16 Saxophone (ten c) English Horn • 8 Tibia Clausa (Pizz.) • 16 Violins 3 Rks (ten c) Violas III • 8 Clarinet Cromorne • 16 Vox Humana (ten c) Vox Humana • 8 Flute Harmonic Flute • 8 English Post Horn French Trompette • 16 Piano Choralbass 4 • 8 Brass Trumpet Trompete • 8 Piano Mixture III • 8 Tuba Mirabilis Tromba • Accomp to Pedal • 8 Trumpet Trumpet • Bass Drum Great to Pedal • 8 Open Diapason Principal • Tap Cymbal (Brush) • 8 Solo Tibia Clausa Bourdon • 8 Tibia Clausa Gedackt ACCOMP • 8 Clarinet Cromorne • 8 English Post Horn French Trompette • 8 Krumet Krumet • 8 Brass Trumpet Trompete • 8 Orchestral Oboe Hautbois • 8 Tuba Mirabilis Tromba • 8 Saxophone English Horn • 8 Trumpet Trumpet • 8 Violins 3 Rks Violas III • 8 Open Diapason Principal • 8 Quintadena Quintadena • 8 Tibia Clausa (m) Gedackt • 8 Concert Flute Harmonic Flute • 8 Clarinet Cromorne • 8 Vox Humana Vox Humana • 8 Violins 3 rks Violas III • 5-1/3 Fifth (Tibia) Quintflöte • 8 Oboe Horn Oboe Horn • 4 Octave Octave • -

Pedal 32 Contra Diaphone C. Bomb 32 Contra Tibia

PEDAL 8 VOX HUMANA (S) 8 TRUMPET 32 CONTRA DIAPHONE C. BOMB 8 VOX HUMANA 8 STYLE D TRUMPET 32 CONTRA TIBIA CLAUSA 4 OCTAVE 8 TUBA HORN 16 BOMBARDE 4 OCTAVE HORN 8 OPEN DIAPASON 16 DOUBLE ENGLISH HORN 4 PICCOLO 8 HORN DIAPASON 16 OPHICLEIDE 4 SOLO STRING 2 RKS 8 SOLO TIBIA CLAUSA 16 DIAPHONE 4 VIOL 2 RKS 8 TIBIA CLAUSA 16 DIAPHONIC HORN 4 GAMBETTE 2 RKS 8 CLARINET 16 SOLO TIBIA CLAUSA 4 LIEBLICH FLUTE 8 KINURA CLARION 4 16 BASS CLARINET 4 CONCERT FLUTE 8 ORCHESTRAL OBOE 16 CONTRA GAMBA 2 RKS 4 VOX HUMANA (M) 8 MUSETTE FRENCH HORN 16 OBOE HORN 2 2/3 TWELFTH 8 KRUMET 16 BOURDON 2 PICCOLO 8 SAXOPHONE 16 GEMSHORN 2 RKS OCTAVE 8 SOLO STRING 2 RKS 8 TUBA MIRABILIS SOLO ON ACCOMP. 8 VIOLIN 2 RKS 8 ENGLISH HORN BOMBARDE 8 GAMBA 2 RKS 8 TUBA HORN MIDI ON ACCOMP. 8 QUINTADENA 8 OPEN DIAPASON 8 PIANO OPEN DIAP. 8 LIEBLICH FLUTE 8 HORN DIAPASON HARP SUB MIXTURE IV 8 VOX HUMANA (S) 8 SOLO TIBIA CLAUSA HARP SCHARF IV 8 VOX HUMANA 8 TIBIA CLAUSA SOLO CHRYSOGLOTT 4 SOLO PICCOLO 8 TIBIA CLAUSA PIZZ. CHRYSOGLOTT MIXTURE III 4 PICCOLO 8 CLARINET SNARE DRUM 2 2/3 SOLO TWELFTH 8 CELLO 2 RKS CASTANETS 2 SOLO PICCOLO 8 FLUTE TAMBOURINE 2 PICCOLO ACCOMP. TO PEDAL WOOD BLOCK 1 3/5 SOLO TIERCE GREAT TO PEDAL TOM-TOM 1 1/3 SOLO LARIGOT SOLO TO PEDAL CHOKE CYMBAL SUB OCTAVE MIDI ON PEDAL TAP CYMBAL UNISON OFF 16 PIANO OPEN DIAP. -

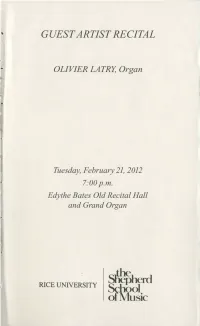

Ofmusic PROGRAM

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL OLIVIER LATRY, Organ Tuesday, February 21, 2012 7:00 p.m. Edythe Bates Old Recital Hall and Grand Organ ~herd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Cortege et litanie Marcel Dupre (1886-1971) ,._ Petite Rapsodie improvisee Charles Tournemire (1870-1939) L'Ascension Olivier Messiaen Majeste du Christ demandant sa gloire a son Pere (1908-1992) Alleluias sereins d 'une ame qui desire le ciel Transports de Joie d 'une ame Priere du Christ montant vers son Pere INTERMISSION Trois danses JehanAlain Joies (1911-1940) Deuils Luttes Improvisation Olivier Latry Olivier Latry is represented by Karen McFarlane Artists, Inc. .. The reverberative acoustics of Edythe Bates Old Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Olivier Latry, titular organist of the Cathedral ofNotre-Dame in Paris, is one of the world's most distinguished organists. He was born in 1962 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, and began his study ofpiano at age 7 and his study of the organ at age 12; he later attended the Academy ofMusic at St. Maur-des-Fosses, studying organ with Gaston Litaize. From 1981 until 1985 Olivier Latry was titular organist ofMeaux Cathedral, and at age 23 he won a competition to become one of the three titular organists of the Ca thedral ofNotre-Dame in Paris. From 1990 until 1995 he taught organ at the Academy ofMusic at St. Maur-des-Fosses, where he succeeded his teacher, Gaston Litaize. Since 1995 he has taught at the Paris Conservatory, where he has succeeded Michel Chapuis. -

M. P. Möller – 3-Manual Organ, 1951 the Robert Turner – 5-Manual Console, 1998 Robert Walker – Digital Sounds, 1998

ORGAN M. P. Möller – 3-Manual Organ, 1951 The Robert Turner – 5-Manual Console, 1998 Robert Walker – Digital Sounds, 1998 Great Choir Swell Solo Organ Organ Organ Organ Gemshorn 16′ Erzähler 16′ Rohrbourdon 16′ Contra Gamba 16′ Bourdon 16′ Principal 8′ Geigen Diapason 8′ Flauto Mirabilis 8′ Montre 8′ Gedeckt 8′ Rohrflöte 8′ Gamba 8′ Principal 8′ Viola 8′ Viole de gambe 8′ Gamba Celeste 8′ Bourdon 8′ Viola Celeste 8′ Voix céleste 8′ Orchestral Flute 4′ Flûte harmonique 8′ Dulciana 8′ Muted Viols II 8′ Posaune 16′ Gemshorn 8′ Unda Maris 8′ Flute Celeste II 8′ Double English Octave 4′ Prestant 4′ Muted Flute Celeste Horn 16′ Flûte octaviante 4′ Koppelflöte 4′ II Orchestral Oboe 8′ Quinte 2 2/3′ Nazard 2 2/3′ Principal 4′ English Horn 8′ Superoctave 2′ Principal 2′ Flûte 4′ Corno di Bassetto 8′ Waldflöte 2′ Tièrce 1 3/5′ Blockflöte 2′ French Horn 8′ Tièrce 1 3/5′ Larigot 1 1/3′ Plein Jeu III- Tuba Mirabilis 8′ Mixture III-IV Sifflöte 1′ IVCymbel III-IV Jubilate Deo (Great) Scharf II-IV Zimbel III-IV Contre Bassoon 16′ Tuba Clarion 4′ Contra Trompete 16′ Cor Anglais 16′ Trompette 8′ Tremolo Trompete 8′ Clarinet 8′ Bassoon 8′ Chimes (Choir) Clarion 4′ Krummhorn 8′ Vox Humana 8′ Harp (Choir) Jubilate Deo 8′ Trompette Clairon 4′ Celesta (Choir) Chimes (Choir) harmonique 8′ Jubilate Deo (Great) Midi Midi Jubilate Deo (Great) Tremolo Solo Sub Great Sub Regal 4′ Midi Solo Unison Off Great Unison Off Chimes Swell Sub Solo Super Great Super Tremolo Swell Unison Off Harp Swell Super Celesta Harp Damper Zimbelstern Choir Sub Choir Unison Off Choir Super Antiphonal Pedal Console Mechanicals The remote style multi level combination Organ Organ system has 32 levels of memory, four ad- Montre 8′ Contre Bourdon 32′ jutable crescendi with a 60 step digital Cor de Nuit 8′ Contre Violone 32′ readout display. -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

The Wanamaker Organ

The Wanamaker Organ Where would you guess the largest operational pipe organ in the world would be located? Believe it or not, it is featured in a spacious 7-story court in Macy’s Center City (formerly Wanamaker’s department store) in Philadelphia, Pa. My wife, Lola, discovered it on a shopping trip while we were in the City of Brotherly Love for an American College of Health Care Administrators meeting last April, and promptly called Dr. Ken Scott and me to come see – and hear – it. The Wanamaker Organ is played twice a day, Monday through Saturday, and more frequently during the Christmas season. In its present configuration, the organ has 28,543 pipes in 462 ranks. The organ console consists of six manuals with an array of stops and controls that command the organ. The organ’s String Division forms the largest single organ chamber in the world. The instrument features 88 ranks of string pipes built by the W.W. Kimball Company of Chicago. The Wanamaker Organ was originally built by the Los Angeles Art Organ Company for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and designed to be the largest organ in the world. After the fair closed, the organ languished in storage until 1909 when it was bought by John Wanamaker for his new department store at 13th and Market streets in Center City, Philadelphia. John Wanamaker (1838 – 1922) was a merchant, religious leader, civic and political figure, considered by some to be the father of modern advertising. He opened his first store in 1861, called Oak Hall, at Sixth and Market streets in Philadelphia, on the site of George Washington’s Presidential Home. -

MX-200 Triune Music “Expanded” Module

MX-200 Triune Music “Expanded” Module TONES Organ tones: 198 Orchestral tones: 148 GM2/GS tones: 386 Others: 512 ORGAN TONES (sampling) REEDS MIXTURES 16’ Chamade IV Grand Cornet 32’ ORGAN FLUES 16’ + 8’ Chamade VIII Gabler Mixture 16’ Montre 16’ + 8’ + 4’ Chamade VI Pedal Grand Mixture 16’ Boudon 16’ Royal Trumpet VI Plein Jeu 16’ Pommer 16’ Posthorn V Gabler Cornet 16’ Quintadena 16’ Heckelphone V Flute Cornet 16’ Dulciana 16’ Posaune V Grand French Mixture 8’ First Diapason 16’ Contre Trompette IV-VI Fourniture (SS) 8’ Second Diapason 16’ + 8’ Voxes IV-VIII Mixutre (HO) 8’ Montre 16’ + 4’ Voxes IV Fourniture 8’ Second Diapason (with Trem) 8’ Tuba Major FFF IV Scharf 8’ Bach Prinzipal 8’ State Trumpet FFF IV Grave Mixture 8’ Gross Flute 8’ Royal Trumpet IV Echo Mixture 8’ Gamba 8’ Royal Tuba IV Rauschquint 8’ Flute Harmonique 8’ Posthorn III Carillon (StE) 8’ Harmonic Flute 8’ Trumpet II Sesquialtera 8’ Harmonic Flute (with Trem) 8’ Trompette II Sesquialtera (with Trem) 8’ Holzgedackt 8’ Regal IV Cornet 4’ 8’ Quintadena 8’ Dulzian IV Cornet 4’ (with Trem) 8’ Quintadena (with Trem) 8’ Dulzian (with Trem) II Quartane 8’ Quintaden 8’ Kinura II Jeu de Clochette 8’ German Gemshorn 8’ Kinura (with Trem) 5-1/3’ Gross Quint 8’ Dulciana 8’ Clarinet 3-1/5’ Gross Terz 8’ & 4’ Bourdon 8’ French Clarinet 8/9’ None 8’ & 2-2/3’ Flute 8’ French Cromorne 8’ & 2’ Gedackt 8’ French Horn CELESTES 5-2/3’ Gross Flute 8’ French Horn (with Trem) 16’ 8’ 4’ + Vox Celestes VII 5-1/3’ Gross Tierce 8’ English Horn 16’ 8’ 4’ Celestes VI 2-2/3’ German Quinte 8’ English -

RTOS Organ Specs As Built

Rochester’s RKO Palace 4/21 Wurlitzer - Opus 1951 12/25/1928 Original specification by house organist Tom Grierson The instrument known today as the RTOS-GRIERSON 4/23 Wurlitzer began life as a 4-manual, 21-rank Special, Opus 1951. It was shipped from North Tonawanda on September 12, 1928 to the new 2916-seat Keith-Albee Palace Theatre (later renamed RKO Palace) on Clinton Avenue North at Mortimer Street in Rochester, NY. It was premiered on Christmas Day of that year by Rochester organist Tom Grierson who is said to have participated significantly in the specification of the instrument. Over the years Wurlitzer historians have often commented that Tom’s British roots are strongly reflected in its design. While Opus1951 is often said to be similar to a Publix #1, there were a number of differences. Besides having one more rank in the solo chamber and a 15 hp blower, other significant variations include: Main chamber: • The Tuba horn (16 ´ - 4 ´) was not placed in the main, but in the solo chamber instead. • The Dulciana and Solo String I ranks were not included in this instrument. • A 15” wp Gamba (16 ´ - 4 ´), Violin (8 ´ - 4 ´) and Violin Celeste (8 ´ - 4 ´ tc) were included. • The Diaphonic Diapason (16 ´ - 8 ´) is 73 notes and has no 4 ´ octave. Solo Chamber: • There was no Vox Humana in the solo. • There is a Horn Diapason (8 ´) in the solo • The Tuba Mirabilis is extended to 16 ´ (wood) Bombarde. • Piano, Sleigh Bells, Vibraphone mechanism and second Xylophone were not included. Console: • No “master” swell pedal. -

Theatre Owner's Manual

TH-202/TH-302 Theatre Models IMPORTANT! Organs which contain GeniSys™ technology no longer include the GeniSys™ Controller Guide within the model specific Owner’s Manual. The correct GeniSys™ Controller Guide must be downloaded and/or printed separately. Please check the CODE version of the software installed within the organ to determine which version of the GeniSys™ Controller Guide is required. The CODE version is briefly displayed within the GeniSys™ Controller’s LCD display when the organ starts up. Copyright © 2016 Allen Organ Company All Rights Reserved AOC P/N 033-00221-1 Revised 10/2016 ALLEN ORGAN COMPANY For more than sixty years--practically the entire history of electronic organs-- Allen Organ Company has built the finest organs that technology would allow. In 1939, Allen built and marketed the world’s first electronic oscillator organ. The tone generators for this instrument used two hundred forty-four vacuum tubes, contained about five thousand components, and weighed nearly three hundred pounds. Even with all this equipment, the specification included relatively few stops. By 1959, Allen had replaced vacuum tubes in oscillator organs with transistors. Thousands of transistorized instruments were built, including some of the largest, most sophisticated oscillator organs ever designed. Only a radical technological breakthrough could improve upon the performance of Allen’s oscillator organs. Such a breakthrough came in conjunction with the United States Space Program in the form of highly advanced digital microcircuits. In 1971, Allen produced and sold the world’s first musical instrument utilizing digitally sampled voices! Your organ is significantly advanced since the first generation Allen digital instrument. -

Woodwind Family

Woodwind Family What makes an instrument part of the Woodwind Family? • Woodwind instruments are instruments that make sound by blowing air over: • open hole • internal hole • single reeds • double reed • free reeds Some woodwind instruments that have open and internal holes: • Bansuri • Daegeum • Fife • Flute • Hun • Koudi • Native American Flute • Ocarina • Panpipes • Piccolo • Recorder • Xun Some woodwind instruments that have: single reeds free reeds • Clarinet • Hornpipe • Accordion • Octavin • Pibgorn • Harmonica • Saxophone • Zhaleika • Khene • Sho Some woodwind instruments that have double reeds: • Bagpipes • Bassoon • Contrabassoon • Crumhorn • English Horn • Oboe • Piri • Rhaita • Sarrusaphone • Shawm • Taepyeongso • Tromboon • Zurla Assignment: Watch: Mr. Gendreau’s woodwind lesson How a flute is made How bagpipes are made How a bassoon reed is made *Find materials in your house that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) can use to make a woodwind (i.e. water bottle, straw and cup of water, piece of paper, etc). *Find some other materials that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) you can make a different woodwind instrument. *What can you do to change the sound of each? *How does the length of the straw effect the sound it makes? *How does the amount of water effect the sound? When you’re done, click here for your “ticket out the door”. Some optional videos for fun: • Young woman plays music from “Mario” on the Sho • Young boy on saxophone • 9 year old girl plays the flute. -

32Nd Sunday in Ordinary Time November 8, 2020

St. Christopher, Marysville Page 1 32nd Sunday in Ordinary Time November 8, 2020 Pope Francis’ Mission Statement: To Become a Band of Joyful Missionary Disciples. Archdiocese of Detroit’s Mission Statement: To Unleash the Gospel. Saint Christopher’s Parish Mission Statement: Transform Lives in Jesus Christ Through the Power and Freedom of the Gospel. Parish Vision Statement: Foster a Personal Encounter with Jesus. Pastor’s Points of Perspective. Greetings and the Father’s Blessing be upon you, my dear spiritual children. What happened to the Sign of Peace at the Mass? As you may recall the Sign of Peace at the Mass was ordered deleted for this time of great fear surrounding the corona virus. Even before the corona virus, parishioners were concerned about the possible exchange of germs between people through the Sign of Peace, which we addressed previously. You may recall that we informed everyone that at the Sign of Peace eye contact and a head nod along with the statement “Peace be with you” would be a sufficient way to exchange the Sign of Peace if one did not want to shake someone’s hand. Recall that the Sign of Peace was based on a “cultural norm,” which commonly, was a handshake. Now we are developing a new and acceptable “cultural norm” of an exchange of a Sign of Peace without any physical con- tact. The Leadership Team and Worship Commission believe it is time to restore some Sign of Peace to the Mass that is culturally acceptable just like the one mentioned above. Therefore, for our cultural standard of today, we will begin restoring the Sign of Peace with eye contact and a head nod along with the statement “Peace be with you” as this is most relevant for our time and circumstances.