Sub-010-Port-Of-Napier-Ltd.Pdf [137

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland Strike

THE MARCH 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Auckland strike 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 1 • march 2018 "On page 14 there is reference to Saida Abad, WHOLE BODY VIBRATION the first female loco 7 engineer in Morocco. I found this billboard with her very moving quote whilst in London recently." Tana Umaga lends a hand to campaign to overcome WBV among LEs. Wayne Butson 10 HISTORIC FIRST General secretary RMTU The entire KiwiRail board made an historic first visit to Hutt workshops Is this the year the recently. MORROCAN CONFERENCE dog bites back? 14 ELCOME to the first issue ofThe Transport Worker magazine for 2018 which, as always, is packed full of just some of the things that your RMTU Union does in the course of its organising for members. delegate Last year ended with a change of Government which should Christine prove to be good news for RMTU members as the governing partners and their sup- Fisiihoi trav- portW partners all have policies which are strongly supportive of rail, ports and the elled all the transport logistics sectors. way to According to the Chinese calendar, 2018 is the year of the dog. However, in my Marrakech view, 2018 is going to be a year of considerable change for RMTU members. We have and was seen Transdev Auckland alter from being a reasonable employer who we have been blown away! doing business with since 2002 to one where dealing with most items has become combative and confrontational. Transdev Wellington is an employer with much less of a working history but we COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Auckland RMTU were able to work with them on the lead up to them taking over the Wellington members pledging solidarity outside Britomart Metro contract and yet, from almost the get go after they took over the running of Place. -

Annual-Report-2017-Stepping-Ahead.Pdf

STEPPING AHEAD ANNUAL REPORT 2017: PART 1of 2 Napier Port is stepping ahead. We’re investing now to build a bright future for our customers, our staff, the economy and our community. CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 2 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT 4 YEAR’S HIGHLIGHTS 6 STEPPING UP 9 FUTURE-PROOFING OUR PORT 10 BUILDING OUR FUTURE 12 A STANDING OVATION 16 OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE 18 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 22 SENIOR MANAGEMENT TEAM 23 BETTER PEOPLE 24 BETTER ANSWERS 26 HEALTH & SAFETY 28 COMMUNITY 30 ENVIRONMENT 32 END OF AN ERA 34 ANNUAL REPORT 2017: PART 1 of 2 • 1 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT It has been a remarkable year for Napier Port. The efforts of staff and the strong leadership of the senior management team enabled Napier Port to respond swiftly to the disruption in the national supply chain caused by the Kaikoura earthquake. Our people and culture are our most important taonga and investing in them has created a stronger company. The health and safety of every person on and significant investment will be required port is the board’s top priority. Reflecting in order to ensure the port can handle this this, the Health and Safety Committee growth in our cargo base. transitioned to a whole-of-board function Napier Port operates in a global this year, emphasising that every director environment and we must sustain our is accountable when it comes to safety. relevance for both shippers and shipping All directors are now spending time in the lines. Having the right infrastructure in operational environment to strengthen place is critical to ensuring shipping lines our understanding of the risks and continue to take our high-value products safety challenges presented by a port to the world at competitive rates. -

Our People Your Growth

OUR PEOPLE YOUR GROWTH PORT OF NAPIER LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CONTENTS RETIRING CHAIRMAN, JIM SCOTLAND 4 CHAIRMAN DESIGNATE, ALASDAIR MACLEOD 5 CENTRAL NEW ZEALAND’S LEADING INTERNATIONAL SEA PORT 6 Napier is Central New Zealand’s leading A DAY IN THE LIFE OF AN EXTENDED international sea port. SUPPLY CHAIN 10 Our customer base extends well beyond FINANCIALS 17 Hawke’s Bay, into the furthest corners of INVESTING FOR THE FUTURE 18 Central New Zealand. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT 22 This year we feature an example of an extended supply chain, one that originates BETTER PEOPLE, BETTER ANSWERS 23 in Karioi, near Ohakune. HEALTH AND SAFETY 28 A partnership between our customer SUSTAINABILITY 29 WPI, KiwiRail and Napier Port… STAKEHOLDER AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 30 A GENERATION ON 31 BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND MANAGEMENT TEAM 34 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 36 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 38 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 41 INCOME STATEMENT 42 STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 42 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 43 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 44 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 45 RECONCILIATION OF SURPLUS AFTER TAXATION TO CASH FLOWS FROM OPERATING ACTIVITIES 46 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 47 AUDITOR’S REPORT 63 Cover: Hughe Ede, Senior Operator, WPI Night Crew Chace Rodda, Launch/Tugmaster 2 PORT OF NAPIER LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PORT OF NAPIER LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2014 3 RETIRING CHAIRMAN, JIM SCOTLAND “It has been a privilege to Chair the Board of increasingly competitive and dynamic environment. Napier Port over a turbulent and challenging period. The results over the past 10 years are clearly shown Notwithstanding major changes in cargo handled and in the table below. -

Annual Report Summary

Te whakapakari tahi i tō tātau taiao. Enhancing our environment together. 2019-2020 Annual Report Summary hbrc.govt.nz hbrc.govt.nz We continue to drive progress toward a healthy environment. 2019-2020 SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT Part 1 – Introduction | Kupu Whakataki 4 Part 2 – Groups of Activities | Ngā Whakaroputanga Kaupapa 16 Part 3 – Financials | Pūronga Pūtea 36 Audit – Independent Auditor’s Report | He Ripoata Arotake Pūtea 40 ISBN Print: 978-0-947499-40-2 ISBN Digital: 978-0-947499-40-2 HBRC Publication Number 5545 Adapting to change~ Three key impacts set the background for the 2019-20 financial year – the global COVID-19 pandemic, a severe drought and the ongoing threat of climate change. [email protected] | +64 6 835 9200 159 Dalton Street. Napier 4110 Private Bag 6006, Napier 4142 hbrc.govt.nz INTRODUCTION KUPU WHAKATI Introduction MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR & CHIEF EXECUTIVE HE KUPU NĀ TE TOIHAU ME TE KAIWHAKAHAERE MATUA Adapting to change “ Three key impacts set the background for the 2019-20 financial year – the global COVID-19 pandemic, a severe drought and the ongoing threat of climate change.” Kia ora koutou It has been an extraordinary year on many levels, The sharemarket float of Napier Port on the New one in which we relied more heavily on technology Zealand Stock Exchange in August 2019 concluded than ever before, for essential service delivery and the Regional Council’s lengthy process to enable to support our own staff forced to work remotely the future-proofing of our Port, releasing the during the COVID-19 lockdown. -

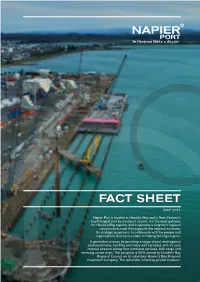

Fact Sheet May 2021

FACT SHEET MAY 2021 Napier Port is located in Hawke’s Bay and is New Zealand’s fourth largest port by container volume. It is the main gateway for Hawke’s Bay exports, and it operates a long-term regional infrastructure asset that supports the regional economy. Its strategic purpose is to collaborate with the people and organisations that have a stake in helping the region grow. It generates revenue by providing a range of port and logistics services (marine, handling and value-add services), with its core revenue streams arising from container services, bulk cargo and servicing cruise ships. The company is 55% owned by Hawke’s Bay Regional Council via its subsidiary Hawke’s Bay Regional Investment Company. The remainder is held by private investors. NAPIER PORT – TE HERENGA WAKA O AHURIRI FACT SHEET • MAY 2021 / 2 NAPIER PORT’S KEY INFRASTRUCTURE CONNECTIONS MAIN PORT SITE – Road AUCKLAND – Rail • 50-hectare site – Ranges • 6 mobile harbour cranes • 1000+ connection points for refrigerated cargo • 42,830m2 warehousing TAURANGA HAMILTON • 38 heavy container handling machines • 16-hectare container storage space 2 ROTORUA • Large on-port packing facility – 8000m • 10 hectares of dedicated log storage • Dedicated stevedoring services, SSA TAUPO GISBORNE • Skilled log marshalling services, ISO and C3 5 WAIROA NEW PLYMOUTH 1 2 6 WHARF OHAKUNE 6 Wharf is a long-term solution which will enable us to NAPIER capitalise on future growth opportunities and continue 3 HASTINGS 1 2 to support our customers, and therefore Hawke’s Bay WHANGANUI 3 and its surrounding regions. Benefits include reduced PALMERSTON NORTH congestion, an ability to handle larger vessels and 1 growth in cruise ship demand, extending the 2 1 Port’s capacity to handle container vessels, THAMES STREET an ability to provide 24-hour berthing CONTAINER DEPOTS of larger container vessels and increased Thames l (left) is for container operational agility and resilience. -

NAPIER PORT – Building for the Future

$15.00 Logistics & Transport Volumenz 18 Issue 3 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CILT NEW ZEALAND March 2020 NAPIER PORT – building for the future Draft New Zealand Rail Plan released RoVE, CoVEs and WDCs – the reform of vocational education ContainerCo’s electric heavy vehicle hits the road ON THE COVER LOGISTICS & TRANSPORT NZ In the first of a series of articles on our IS THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF nation’s air and sea ports, the Napier Port THE CHARTERED INSTITUTE OF team explain how they are building for the LOGISTICS & TRANSPORT NZ future – see page 12 Photo courtesy of Napier Port 6 Contents Our rising stars 3 Ken Gilligan awarded Life Membership certificate 5 Report on the 2019 China International Logistics Summit 6 Draft New Zealand Rail Plan released 8 RoVE, CoVEs and WDCs – the reform of vocational education 11 8 Napier Port – building for the future 12 ContainerCo’s electric heavy vehicle hits the road 15 Pathway from fossil fuels to sustainable resilient solutions (part II) 16 RCG delivers infrastructure to far-flung corners of NZ 18 In the next edition The editorial team welcomes expressions of interest for submitting an article for the June 2020 edition of this journal. Contributors should in the first instance contact the editorial convenor, Murray King (email [email protected]) to discuss their article. 15 Deadline for the June edition: Tuesday 28 April 2020 12 18 SPREAD THE WORD ABOUT CILT … If you enjoy reading this magazine and think others would too, please share it with others – forward to a friend or leave a printed -

Proposed Wharf and Dredging Project

PROPOSED WHARF AND DREDGING PROJECT RESOURCE CONSENT APPLICATIONS AND DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTS ON THE ENVIRONMENT: VOLUME 1 PREPARED FOR PORT OF NAPIER LTD NOVEMBER 2017 PROPOSED WHARF AND DREDGING PROJECT RESOURCE CONSENT APPLICATIONS AND DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTS ON THE ENVIRONMENT PREPARED FOR PORT OF NAPIER LTD NOVEMBER 2017 – VOLUME 1 Allan Planning and Research Ltd QUALITY STATEMENT Project Manager: Michel de Vos, Port of Napier Ltd Document Prepared By: Sylvia Allan, Allan Planning and Research Ltd Grant Russell, Stantec New Zealand Reviewed By: Napier Port Programme Steering Group Lara Blomfield – Sainsbury, Logan & Williams Paul Majurey – Atkins, Holm, Majurey Allan Planning and Research Ltd Napier Port Proposed Wharf and Dredging Project – VOLUME 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. I Proposal .................................................................................................................................................................. i Proposed New Wharf (Wharf 6) .............................................................................................................................. i Proposed Dredging .................................................................................................................................................. i Proposed Disposal Area ........................................................................................................................................ -

Fact Sheet December 2019

FACT SHEET DECEMBER 2019 Napier Port is located in Hawke’s Bay and is New Zealand’s fourth largest port by container volume. It is the main gateway for Hawke’s Bay exports, and it operates a long-term regional infrastructure asset that supports the regional economy. Its strategic purpose is to collaborate with the people and organisations that have a stake in helping the region grow. It generates revenue by providing a range of port and logistics services (marine, handling and value-add services), with its core revenue streams arising from container services, bulk cargo and servicing cruise ships. The company is 55% owned by Hawke’s Bay Regional Council via its subsidiary Hawke’s Bay Regional Investment Company. The remainder is held by private investors. NAPIER PORT – TE HERENGA WAKA O AHURIRI FACT SHEET • DECEMBER 2019 / 2 NAPIER PORT’S KEY INFRASTRUCTURE CONNECTIONS MAIN PORT SITE – Road AUCKLAND – Rail • 50-hectare site – Ranges • 6 mobile harbour cranes • 1000+ connection points for refrigerated cargo • 42,830m2 warehousing TAURANGA HAMILTON • 34 heavy container handling machines • 16-hectare container storage space 2 ROTORUA • Large on-port packing facility – 8000m • 10 hectares of dedicated log storage • Dedicated stevedoring services, SSA TAUPO GISBORNE • Skilled log marshalling services, ISO and C3 5 WAIROA NEW PLYMOUTH 1 2 6 WHARF OHAKUNE 6 Wharf is a long-term solution which will enable us to NAPIER capitalise on future growth opportunities and continue 3 HASTINGS 1 2 to support our customers, and therefore Hawke’s Bay WHANGANUI 3 and its surrounding regions. Benefits include reduced PALMERSTON NORTH congestion, an ability to handle larger vessels and 1 growth in cruise ship demand, extending the 2 1 Port’s capacity to handle container vessels, THAMES an ability to provide 24-hour berthing STREET I & II of larger container vessels and increased Empty Container Depot operational agility and resilience. -

FFP NZ De.Pdf

In Kraft seit LAND Neuseeland 04/06/2021 00341 ABSCHNITT Fischereierzeugnisse Datum der Veröffentlichung 28/07/2007 Liste in Kraft Zulassungsnummer Name Stadt Regionen Aktivitäten Bemerkung Datum der Abfrage 2005 Seadragon Marine Oils Limited Nelson Nelson PP Aq 15/11/2011 255 New Zealand Food Innovation Auckland Limited Auckland Auckland PP 13/08/2020 289 New Zealand Food Innovation (Waikato) Limited Hamilton PP 25/09/2018 517 Alaron Products Limited Nelson Nelson PP Aq 29/10/2013 9681 O2B Healthy Limited Nelson Nelson PP 12/09/2019 AFM1 Auckland Fish Market Limited Auckland Auckland PP AROMA4 Aroma (N.Z.) Limited Havelock Marlborough PP 28/06/2017 BIOMER04 Bio-Mer Limited Christchurch Canterbury PP Aq 20/08/2009 CBC01 Cloudy Bay Clams Limited Havelock Marlborough PP 01/08/2021 CC084 Pakihi Marine Farms Limited Auckland Auckland PP CHANDLER01 Talley's Group Limited Riverlands CS 12/02/2016 DFNZ1 Dry Food NZ Limited Havelock Marlborough PP DGF99 DHL Global Forwarding (New Zealand) Limited Christchurch Canterbury CS 07/10/2020 FFNZ1 Triple Treasure Health Foods Limited Christchurch Canterbury PP Aq 03/09/2021 FLC04 Fiordland Lobster Company Limited Ward Marlborough PP 19/05/2020 1 / 11 Liste in Kraft Zulassungsnummer Name Stadt Regionen Aktivitäten Bemerkung Datum der Abfrage FOODPRO1 Polarcold Stores Limited Christchurch Canterbury CS FPH3 Sanford Limited Timaru Canterbury PP FPH52 Sanford Limited Auckland Auckland PP GMS1 Rex Gapper Trading As G & M Seafoods Blenheim Marlborough PP 03/03/2021 GNF001 Nino's Limited T/a Grenada North Fisheries -

Modeling New Zealand's Log's Supply Chain : a Two-Tiered Modeling

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Modeling New Zealand’s Log’s Supply Chain: A Two-Tiered Modeling Approach of Logistical Network Resilience A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Supply Chain Management At Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Mohammed Zuhair Hassan Alaqqad 2017 1 Abstract The global characteristic of today’s market raise concerns regarding the compatibility between the different nodes within a supply chain. Political, economic, infrastructural, cultural and other risks should be considered when operating globally. Tsunamis, strikes, hurricanes, bio-security threats and wars and their impact on the logistical networks are all examples of major events that might happen in a certain place and affect other supply chain members in other parts of the world. This type of events and their disastrous consequences show the importance of being ready and having a contingency plan for such events to minimize their effect on the companies’ supply chains The objective of this research is to provide the building bricks of a tool that functions as a decision support system to help practitioners in the log industry deciding their course of action spontaneously in response to sudden major events that might disrupt their supply chains. The resulting decision support system and recommendations of this research aim at improving the resilience of the log supply chain in New Zealand and the logistical network in general. -

Fact Sheet May 2020

FACT SHEET MAY 2020 Napier Port is located in Hawke’s Bay and is New Zealand’s fourth largest port by container volume. It is the main gateway for Hawke’s Bay exports, and it operates a long-term regional infrastructure asset that supports the regional economy. Its strategic purpose is to collaborate with the people and organisations that have a stake in helping the region grow. It generates revenue by providing a range of port and logistics services (marine, handling and value-add services), with its core revenue streams arising from container services, bulk cargo and servicing cruise ships. The company is 55% owned by Hawke’s Bay Regional Council via its subsidiary Hawke’s Bay Regional Investment Company. The remainder is held by private investors. NAPIER PORT – TE HERENGA WAKA O AHURIRI FACT SHEET • MAY 2020 / 2 NAPIER PORT’S KEY INFRASTRUCTURE CONNECTIONS MAIN PORT SITE – Road AUCKLAND – Rail • 50-hectare site – Ranges • 6 mobile harbour cranes • 1000+ connection points for refrigerated cargo • 42,830m2 warehousing TAURANGA HAMILTON • 38 heavy container handling machines • 16-hectare container storage space 2 ROTORUA • Large on-port packing facility – 8000m • 10 hectares of dedicated log storage • Dedicated stevedoring services, SSA TAUPO GISBORNE • Skilled log marshalling services, ISO and C3 5 WAIROA NEW PLYMOUTH 1 2 6 WHARF OHAKUNE 6 Wharf is a long-term solution which will enable us to NAPIER capitalise on future growth opportunities and continue 3 HASTINGS 1 2 to support our customers, and therefore Hawke’s Bay WHANGANUI 3 and its surrounding regions. Benefits include reduced PALMERSTON NORTH congestion, an ability to handle larger vessels and 1 growth in cruise ship demand, extending the 2 1 Port’s capacity to handle container vessels, THAMES STREET an ability to provide 24-hour berthing CONTAINER DEPOTS of larger container vessels and increased Thames l (left) is for container operational agility and resilience. -

COUNTRY SECTION New Zealand Fishery Products

Validity date from COUNTRY New Zealand 04/06/2021 00341 SECTION Fishery products Date of publication 28/07/2007 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 2005 Seadragon Marine Oils Limited Nelson Nelson PP Aq 15/11/2011 255 New Zealand Food Innovation Auckland Limited Auckland Auckland PP 13/08/2020 289 New Zealand Food Innovation (Waikato) Limited Hamilton PP 25/09/2018 517 Alaron Products Limited Nelson Nelson PP Aq 29/10/2013 9681 O2B Healthy Limited Nelson Nelson PP 12/09/2019 AFM1 Auckland Fish Market Limited Auckland Auckland PP AROMA4 Aroma (N.Z.) Limited Havelock Marlborough PP 28/06/2017 BIOMER04 Bio-Mer Limited Christchurch Canterbury PP Aq 20/08/2009 CBC01 Cloudy Bay Clams Limited Havelock Marlborough PP 01/08/2021 CC084 Pakihi Marine Farms Limited Auckland Auckland PP CHANDLER01 Talley's Group Limited Riverlands CS 12/02/2016 DFNZ1 Dry Food NZ Limited Havelock Marlborough PP DGF99 DHL Global Forwarding (New Zealand) Limited Christchurch Canterbury CS 07/10/2020 FFNZ1 Triple Treasure Health Foods Limited Christchurch Canterbury PP Aq 03/09/2021 FLC04 Fiordland Lobster Company Limited Ward Marlborough PP 19/05/2020 1 / 11 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request FOODPRO1 Polarcold Stores Limited Christchurch Canterbury CS FPH3 Sanford Limited Timaru Canterbury PP FPH52 Sanford Limited Auckland Auckland PP GMS1 Rex Gapper Trading As G & M Seafoods Blenheim Marlborough PP 03/03/2021 GNF001 Nino's Limited T/a Grenada North Fisheries Wellington Wellington