The Legacy of Charles Marlatt and Efforts to Limit Plant Pest Invasions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Concert Series: Nature's Symphony

Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org ribbit chirp chirp Seasonal Sightings Environmental Adventures The buzzzz Whether it’s chirping chipmunks, singing birds, or calling katydids, Sounds of one thing is for sure—sounds will abound this summer in Conservation Summer Concert Series: District sites. It’s easy to experience the chorus. Just head to one of our Summer 32 sites and venture out onto the trails. Try the activities below, and Nature’s Symphony listen to as many nature sounds as you can this summer. by Kim Compton, Education Program Coordinator Broadwinged katydid The beauty of nature is well Can you make these animal sounds? documented – with scenic vistas, photographs, and paintings; but Snowy tree cricket Run your finger down the teeth Clemson University–USDA Cooperative Extension have you ever really stopped Slide Series, Bugwood.org of a comb to make a sound like a chorus frog call. to listen to nature? A veritable symphony of sounds greets us every time we venture out into the great Rub two pieces of sandpaper outdoors. Summertime is an especially musical time. together to make a sound American tree sparrow like a grasshopper calling. Bob Williams Bob Birds can have harsh down or speeds up based on calls, sweet songs, and everything in between. Visit the the temperature. This means wetlands to hear the ever-present “conk-a-reeeee” call of we can try to approximate the the red-winged blackbird. You may also be rewarded with a evening temperature by listening suddenly loud and resonating cry of a nesting sandhill crane to cricket chirps! The Farmer’s MAKE A SOUND MAP! or the almost-maniacal whinny of the seldom seen sora rail. -

San Jose Scale and Its Natural Enemies: Investigating Natural Or Augmented Controls

California Tree Fruit Agreement Research Report 2002 SAN JOSE SCALE AND ITS NATURAL ENEMIES: INVESTIGATING NATURAL OR AUGMENTED CONTROLS Project Leaders: Kent M. Daane Cooperators: Glenn Y. Yokota, Walter J. Bentley, Karen Sime, and Brian Hogg ABSTRACT San Jose scale (SJS) and its natural enemies were studied from 1999 through 2002. Natural populations were followed in stone fruit and almond blocks, with orchard management practices divided into “conventional” and “sustainable” practices, based on dormant and in-season insecticide use. Results generally show higher fruit damage at harvest-time in sustainably managed fields, although, these results are not consistent among orchards and exceptions to this pattern were found. In conventionally managed blocks, later harvest dates resulted in higher SJS fruit damage, although this did not hold true in sustainably managed orchards. Results from SJS pheromone-baited traps show a predominant seasonal pattern of SJS densities progressively increasing and parasitoid (Encarsia perniciosi) densities progressively decreasing. These data are discussed with respect to SJS fruit damage and parasitoid establishment and efficiency. SJS and parasitoid sampling methodology and distribution were investigated. Comparing SJS pheromone trap data to numbers of crawlers on double-sided sticky tape and SJS infested fruit at harvest show a significant correlation between pheromone trap counts of SJS males and numbers of SJS crawlers. Results suggest that there is a small window in the season (April-May) when sticky tape provides important information on crawler abundance and damage. Results show a negative correlation between the early season abundance of Encarsia (as measured by pheromone traps) and SJS damage at harvest. These results suggest that early-season ratios of parasitoid : SJS can not be used to predict fruit damage or biological control (these data require more analysis). -

Bionomics of Chilocorus Infernalis Mulsant, 1853 (Coleoptera

doi:10.14720/aas.2019.113.1.07 Original research article / izvirni znanstveni članek Bionomics of Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853 (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), a predator of San Jose scale, Diaspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock, 1881) under laboratory conditions Razia RASHEED1*, A.A. BUHROO1 and Shaziya GULL1 Received July 23, 2018; accepted January 03, 2019. Delo je prispelo 23. julija 2018, sprejeto 03. januarja 2019. ABSTRACT IZVLEČEK The bionomics of Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853, a BIONOMIJA VRSTE Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853 natural enemy of San Jose scale, was studied under laboratory (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), PLENILCA AMERIŠKEGA conditions (26 ± 2˚C, and 65 ± 5% relative humidity). The KAPARJA (Diaspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock, 1881)) V eggs were deposited in groups and on average 45.68 ± 24.70 LABORATORIJSKIH RAZMERAH eggs were laid by female. Mean observed incubation period was 6.33 ± 1.52 days. Four instar grubs were observed, and Bionomija vrste Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853, mean duration of all four grubs was found to be 19.98 days. naravnega sovražnika ameriškega kaparja, je bila preučevana The pupal stage lasted for 8.00 ± 0.50 days and after adults v laboratorijskih razmerah (26 ± 2˚C in 65 ± 5 % relativne emerged out. zračne vlažnosti). Samice plenilca so jajčeca odlagale v skupinah, v poprečju 45,68 ± 24,70 jajčec na samico. V Key words: bionomics; natural enemies; San Jose scale; povprečju so se ličinke razvile iz jajčec v 6,33 ± 1,52 dneh. incubation period; larval instars Ugotovljene so bile štiri larvalne stopnje, katerih povprečna življenska doba je bila 19,98 dni. Razvojni štadij bube je trajal 8,00 ± 0,50 dni, nakar so se izlegli imagi. -

(Ceroplastes Destructor) and Chinese Wax Scale (C. Sinesis) (Hemi

POPULATION ECOLOGY AND INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF SOFT WAX SCALE (CEROPLASTES DESTRUCTOR) AND CHINESE WAX SCALE (C. SINENSIS) (HEMIPTERA: COCCIDAE) ON CITRUS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Lincoln University Peter L. La Lincoln University 1994 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. POPUlATION ECOWGY AND INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF SOFT WAX SCALE (CEROPLASTES DESTRUCTOR) AND CHINESE WAX SCALE (c. SINENSIS) (HEMIPTERA: COCCIDAE) ON CITRUS Peter L. La Soft wax scale (SWS) Ceroplastes destructor (Newstead) and Chinese wax scale (CWS) C. sinensis Del Guercio (Hemiptera: Coccidae) are indirect pests of citrus (Citrus spp.) in New Zealand. Honeydew they produce supports sooty mould fungi that disfigure fruit and reduce photosynthesis and fruit yield. Presently, control relies on calendar applications of insecticides. The main aim of this study was to provide the ecological basis for the integrated management of SWS and CWS. Specific objectives were to compare their population ecologies, determine major mortality factors and levels of natural control, quantify the impact of ladybirds on scale populations, and evaluate pesticides for compatibility with ladybirds. Among 57 surveyed orchards, SWS was more abundant than CWS in Kerikeri but was not found around Whangarei. Applications of organophosphates had not reduced the proportion of orchards with medium or high densities of SWS. Monthly destructive sampling of scale populations between November 1990 and February 1994 was supplemented by in situ counts of scale cohorts. Both species were univoltine, but SWS eggs hatched two months earlier than those of CWS, and development between successive instars remained two to three months ahead. -

17 Year Periodical Cicada - Magicicada Cassini and Magicicada Septendecim

Problem: 17 Year Periodical Cicada - Magicicada cassini and Magicicada septendecim Hosts: Over 270 species of plants serve as hosts though the most preferred plants include maple, hickory, hawthorn, apple, peach, cherry, and pear. Pine and spruce trees are not damaged. Description: Periodical cicadas show up every 17 years in Kansas with 2015 being the last year of emergence. The year of emergence varies with location. For example, a brood of periodical cicadas emerged in 2013 in Maryland, Virginia, and portions of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and North Carolina. Since our last year of emergence was 2015, our next will be 2032. However, there are always some cicadas that emerge 4 years early. Therefore, we will see a partial emergence in 2028. The bodies of periodical cicadas are basically black but the basal portions of the wing veins are distinctly orange and the eyes are reddish/orangish. No other species of cicada in Kansas fits this description. Cicadas do not sting or bite. Life History: In May and June of the year of emergence, matured nymphs will emerge from the ground and climb onto trees, bushes and other upright structures. After securing a good foothold, a split will form at the head end of each nymph, and the adult will emerge. Female cicadas will use their ovipositors to insert eggs beneath the bark of twigs and branches on a wide variety of trees and shrubs. Eggs will hatch in seven to eight weeks, and the nymphs will drop to the ground, burrowing as deep as 24 inches into the ground until they find suitable roots upon which to feed. -

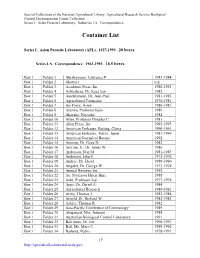

Container List

Special Collections of the National Agricultural Library: Agricultural Research Service Biological Control Documentation Center Collection Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory. Subseries I.A. Correspondence. Container List Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory (APL). 1927-1993. 20 boxes. Series I.A. Correspondence. 1963-1993. 16.5 boxes. Box 1 Folder 1 Abrahamson, Lawrence P. 1983-1984 Box 1 Folder 2 Abstract n.d. Box 1 Folder 3 Academic Press, Inc. 1986-1993 Box 1 Folder 4 Achterberg, Dr. Kees van 1982 Box 1 Folder 5 Aeschlimann, Dr. Jean-Paul 1981-1985 Box 1 Folder 6 Agricultural Counselor 1976-1981 Box 1 Folder 7 Air Force, Army 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 8 Aizawa, Professor Keio 1986 Box 1 Folder 9 Akasaka, Naoyuki 1982 Box 1 Folder 10 Allen, Professor Douglas C. 1981 Box 1 Folder 11 Allen Press, Inc. 1992-1993 Box 1 Folder 12 American Embassy, Beijing, China 1990-1991 Box 1 Folder 13 American Embassy, Tokyo, Japan 1981-1990 Box 1 Folder 14 American Journal of Botany 1992 Box 1 Folder 15 Amman, Dr. Gene D. 1982 Box 1 Folder 16 Amrine, Jr., Dr. James W. 1986 Box 1 Folder 17 Anderson, Don M. 1981-1983 Box 1 Folder 18 Anderson, John F. 1975-1976 Box 1 Folder 19 Andres, Dr. Lloyd 1989-1990 Box 1 Folder 20 Angalet, Dr. George W. 1973-1978 Box 1 Folder 21 Annual Reviews Inc. 1992 Box 1 Folder 22 Ao, Professor Hsien-Bine 1988 Box 1 Folder 23 Aoki, Professor Joji 1977-1978 Box 1 Folder 24 Apps, Dr. Darrel A. 1984 Box 1 Folder 25 Agricultural Research 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 26 Army, Thomas J. -

Periodical Cicadas SP 341 3/21 21-0190 Programs in Agriculture and Natural Resources, 4-H Youth Development, Family and Consumer Sciences, and Resource Development

SP 341 Periodical Cicadas Frank A. Hale, Professor Originally developed by Harry Williams, former Professor Emeritus and Jaime Yanes Jr., former Assistant Professor Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology The periodical cicada, Magicicada species, has the broods have been described by scientists and are longest developmental period of any insect in North designated by Roman numerals. There are three 13-year America. There is probably no insect that attracts as cicada broods (XIX, XXII and XXIII) and 12 17-year much attention in eastern North America as does the cicada broods (I-X, XIII, and XIV). Also, there are three periodical cicada. Their sudden springtime emergence, distinct species of 17-year cicadas (M. septendecim, filling the air with their high-pitched, shrill-sounding M. cassini, and M. septendecula) and three species of songs, excites much curiosity. 13-year cicadas (M. tredecim, M. tredecassini, and M. tredecula). Two races of the periodical cicada exist. One race has a life cycle of 13 years and is common in the southeastern In Tennessee, Brood XIX of the 13-year cicada had a United States. The other race has a life cycle of 17 years spectacular emergence in 2011 (Map 1). In 2004 and and is generally more northern in distribution. Due 2021, Brood X of the 17-year cicada primarily emerged to Tennessee’s location, both the 13-year and 17-year in East Tennessee (Map 2). Brood X has the largest cicadas occur in the state. emergence of individuals for the 17-year cicada in the United States. Brood XXIII of the 13-year cicada last Although periodical cicadas have a 13- or 17-year cycle, emerged in West Tennessee in 2015 (Map 3). -

Periodical Cicada, 17-Year Locusts

Pest Profile Photo credit: Jim Kalisch, University of Nebraska - Lincoln Common Name: Periodical cicada, 17-year locusts Scientific Name: Magicicada septendecim (Linnaeus) Order and Family: Hemiptera, Cicadidae Size and Appearance: This species of cicada goes through a 17-year life cycle. The nymphs live underground, feeding and growing for 17 years, then emerge in large numbers to breed and start the cycle again. When the nymphs emerge, they find a tree to climb and shed their skin. The different broods that occur every 17 years are given specific Roman numeral designations. Males sing using a special organ to produce a loud noise that attracts the females to mate. Length (mm) Appearance Egg Eggs rice like in appearance. The eggs are laid in branches of trees in slits, where they hatch and drop to the ground. They burrow into the ground, where they remain for the rest of their nymphal life. Larva/Nymph Tan or brownish in color, no wings, front legs modified for burrowing and clinging on tree. Nymphs undergo five instar stages, growing slowly for 17 years. Most of the life cycle is spent underground until it emerges and molts to an adult to mate. Adult 27-30mm, Adults have black bodies, red eyes, and membranous reddish wingspan 76mm orange wings. Can crawl and fly; short antennae; 3 ocelli; males sing loud choruses, females don’t sing. Pupa (if applicable) Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Nymphs and Adults: Piercing-sucking Host plant/s: They feed on a wide variety of deciduous trees and roots of trees. Description of Damage (larvae and adults): As nymphs, the periodical cicadas suck juices and nutrients from roots of trees. -

The Evolutionary Relationships of 17-Year and 13-Year Cicadas, and Three New Species (Hornoptera, Cicadidae, Magicicada)

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 121 The Evolutionary Relationships of 17-Year and 13-Year Cicadas, and Three New Species (Hornoptera, Cicadidae, Magicicada) BY KlCHAKD D. ALEXANDEK AND THOMAS E. MOORE ANN ARBOR MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN JULY 24, 1962 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradsliaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication d which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume. a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and indi- viduals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum tech- niques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan. No. 1. Directions for collecting and preserving specimens of dragonflies for museum purposes. By E. B. WILLIAMSON.(1916) 15 pp., 3 figs. .......... $0.25 No. -

The Effects of a Periodic Cicada Emergence on Forest Birds and the Ecology of Cerulean Warblers at Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge, Indiana

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2006 The Effects of a Periodic Cicada Emergence on Forest Birds and the Ecology of Cerulean Warblers at Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge, Indiana Dustin W. Varble University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Varble, Dustin W., "The Effects of a Periodic Cicada Emergence on Forest Birds and the Ecology of Cerulean Warblers at Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge, Indiana. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4519 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Dustin W. Varble entitled "The Effects of a Periodic Cicada Emergence on Forest Birds and the Ecology of Cerulean Warblers at Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge, Indiana." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. David A. Buehler, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Frank Van Manen, Roger Tankersley Jr. Joseph R. Robb Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

AA00023276 00001.Pdf

UBRAR ST ATE PLANT BOA N E.W S LETTER BUREAU OF PLANT QU~AANTINE • UNITED SThTES DEPhRTNiENT OF AGRICULTURE --=============:========= ========= Number 21 (NOT FOR PUBLICATION) September 1, 1932. ----------- ====-- Repairs to Me xican border car fumigati6n houses are rapidly being completed. Extension to the rear of the Eagle Pass plant permitting accom modation of a 50-foot car in a s ingle compartment and i nstallation o~ sliding end doors were finished about July 1. ~ partition door of the sliding type was installed during the month of July at the Brownsville house to replace a set of the double swing type. Work at Nogal es covered by contra ct is more than half finished and the completed installations i nclude sliding end doors, HCN gas disposal system, and new wall at rear of house, designed to elimi nate flooding of the fw,1i ga tion chambers during the seasonal floods whi ch periodically inundate that part of Nogales where the plant is located. That this new r ear wall apparently functions properly i~ evidenced by the fact that on July 9, during a flood which it is claimed reached ~he highest level ever r ecorded, no water enter ed the rear of the fumigation house. ~ . C, Johnson reports the completion of the tests on fumi gation of cot ton s~~les with carbon disulphide, He was able to obtain complete mortality of pink bollwotm in infested seed with a reasonable time of exposure. h new type of fumigation chamber for small quantities of cotton samples was designed and tested. This apparatus gave very good results, is chea p, and easy to op erate, -2-- RECENT ENTOMOLOGICAL INTERCEPTIONS OF INTEREST Q~Li.D!it flL.f£2m:...M~xi.£Q.-~Larvae of the dark fruit fly (~n~tre:Q.ha ~.~.!]2~!!B!2§ Wied.) were intercepted at El Pa:s o and Hidalgo, Tex.,. -

Cicadas - Getting Ready for Brood X

Best Management Practices Cicadas - Getting Ready for Brood X This year marks the emergence of Brood X throughout the Mid-Atlantic States. Experts are predicting this year’s emergence to be the most numerous in history. These Periodical cicadas (belonging to the genus Magicicada) are considered nuisance pests and do not bite, sting, and pose no danger to humans. They belong to a group of insects know as the Homopterans, which include other insects like treehoppers, leafhoppers and spittlebugs. The loud songs produced by male cicadas are notorious and are specific to each species. These sounds may come from abdominal contortions or wing-banging. Periodical cicadas are may be referred to as "17-year locusts." Early American colonists had never seen periodical cicadas. They were familiar with the biblical story of locust plagues in Egypt and Palestine, but were not sure what kind of insect was being described. When the cicadas appeared by the millions, some of these early colonists thought a "locust plague" had come upon them. Some American Indians thought their periodic appearance had an evil significance. The confusion between cicadas and locusts exists today in that cicadas are commonly called locusts. The term "locust" is correctly applied only to certain species of grasshoppers. There are six species of periodical cicadas, three with a 17-year cycle and three with a 13-year cycle. The three species in each life-cycle group are distinctive in size, color, and song. The 17-year cicadas are generally northern, and the 13-year cicadas southern with considerable overlap. In fact, both life-cycle types may occur in the same forest (but emerge together every 221 years).