San Jose Scale and Its Natural Enemies: Investigating Natural Or Augmented Controls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphology and Adaptation of Immature Stages of Hemipteran Insects

© 2019 JETIR January 2019, Volume 6, Issue 1 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Morphology and Adaptation of Immature Stages of Hemipteran Insects Devina Seram and Yendrembam K Devi Assistant Professor, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Punjab Introduction Insect Adaptations An adaptation is an environmental change so an insect can better fit in and have a better chance of living. Insects are modified in many ways according to their environment. Insects can have adapted legs, mouthparts, body shapes, etc. which makes them easier to survive in the environment that they live in and these adaptations also help them get away from predators and other natural enemies. Here are some adaptations in the immature stages of important families of Hemiptera. Hemiptera are hemimetabolous exopterygotes with only egg and nymphal immature stages and are divided into two sub-orders, homoptera and heteroptera. The immature stages of homopteran families include Delphacidae, Fulgoridae, Cercopidae, Cicadidae, Membracidae, Cicadellidae, Psyllidae, Aleyrodidae, Aphididae, Phylloxeridae, Coccidae, Pseudococcidae, Diaspididae and heteropteran families Notonectidae, Corixidae, Belastomatidae, Nepidae, Hydrometridae, Gerridae, Veliidae, Cimicidae, Reduviidae, Pentatomidae, Lygaeidae, Coreidae, Tingitidae, Miridae will be discussed. Homopteran families 1. Delphacidae – Eg. plant hoppers They comprise the largest family of plant hoppers and are characterized by the presence of large, flattened spurs at the apex of their hind tibiae. Eggs are deposited inside plant tissues, elliptical in shape, colourless to whitish. Nymphs are similar in appearance to adults except for size, colour, under- developed wing pads and genitalia. 2. Fulgoridae – Eg. lantern bugs They can be recognized with their antennae inserted on the sides & beneath the eyes. -

Insetos Do Brasil

COSTA LIMA INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO HEMÍPTEROS ESCOLA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA SÉRIE DIDÁTICA N.º 3 - 1940 INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO HEMÍPTEROS A. DA COSTA LIMA Professor Catedrático de Entomologia Agrícola da Escola Nacional de Agronomia Ex-Chefe de Laboratório do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO CAPÍTULO XXII HEMÍPTEROS ESCOLA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA SÉRIE DIDÁTICA N.º 3 - 1940 CONTEUDO CAPÍTULO XXII PÁGINA Ordem HEMÍPTERA ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Superfamília SCUTELLEROIDEA ............................................................................................................ 42 Superfamília COREOIDEA ............................................................................................................................... 79 Super família LYGAEOIDEA ................................................................................................................................. 97 Superfamília THAUMASTOTHERIOIDEA ............................................................................................... 124 Superfamília ARADOIDEA ................................................................................................................................... 125 Superfamília TINGITOIDEA .................................................................................................................................... 132 Superfamília REDUVIOIDEA ........................................................................................................................... -

Data Sheets on Quarantine Pests

Prepared by CABI and EPPO for the EU under Contract 90/399003 Data Sheets on Quarantine Pests Aonidiella citrina IDENTITY Name: Aonidiella citrina (Coquillett) Synonyms: Aspidiotus citrinus Coquillett Chrysomphalus aurantii citrinus (Coquillett) Taxonomic position: Insecta: Hemiptera: Homoptera: Diaspididae Common names: Yellow scale (English) Cochenille jaune (French) Escama amarilla de los cítricos (Spanish) Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature: The original description by Coquillett is inadequate and simply refers to 'the yellow scale' on orange (Nel, 1933). A. citrina is morphologically very similar to the Californian red scale, Aonidiella aurantii (Maskell), and was considered to be a variety until Nel (1933) raised it to specific level based on a comparative study of their ecology, biology and morphology. Bayer computer code: AONDCI EU Annex designation: II/A1 HOSTS A. citrina is polyphagous attacking plant species belonging to more than 50 genera in 32 families. The main hosts of economic importance are Citrus spp., especially oranges (C. sinensis), but the insect is also recorded incidentally on a wide range of ornamentals and some fruit crops including Acacia, bananas (Musa paradisiaca), Camellia including tea (C. sinensis), Clematis, Cucurbitaceae, Eucalyptus, Euonymus, guavas (Psidium guajava), Hedera helix, Jasminum, Ficus, Ligustrum, Magnolia, mangoes (Mangifera indica), Myrica, olives (Olea europea), peaches (Prunus persica), poplars (Populus), Rosa, Schefflera actinophylla, Strelitzia reginae, Viburnum and Yucca. The main potential hosts in the EPPO region are Citrus spp. growing in the southern part of the region, around the Mediterranean. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION A. citrina originated in Asia and has spread to various tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world. The precise distribution of A. -

A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods

insects Review A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods in Agroecosystems Kenneth W. McCravy Department of Biological Sciences, Western Illinois University, 1 University Circle, Macomb, IL 61455, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-309-298-2160 Received: 12 September 2018; Accepted: 19 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Beneficial arthropods provide many important ecosystem services. In agroecosystems, pollination and control of crop pests provide benefits worth billions of dollars annually. Effective sampling and monitoring of these beneficial arthropods is essential for ensuring their short- and long-term viability and effectiveness. There are numerous methods available for sampling beneficial arthropods in a variety of habitats, and these methods can vary in efficiency and effectiveness. In this paper I review active and passive sampling methods for non-Apis bees and arthropod natural enemies of agricultural pests, including methods for sampling flying insects, arthropods on vegetation and in soil and litter environments, and estimation of predation and parasitism rates. Sample sizes, lethal sampling, and the potential usefulness of bycatch are also discussed. Keywords: sampling methodology; bee monitoring; beneficial arthropods; natural enemy monitoring; vane traps; Malaise traps; bowl traps; pitfall traps; insect netting; epigeic arthropod sampling 1. Introduction To sustainably use the Earth’s resources for our benefit, it is essential that we understand the ecology of human-altered systems and the organisms that inhabit them. Agroecosystems include agricultural activities plus living and nonliving components that interact with these activities in a variety of ways. Beneficial arthropods, such as pollinators of crops and natural enemies of arthropod pests and weeds, play important roles in the economic and ecological success of agroecosystems. -

Biological Control of Insect Pests in the Tropics - M

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT – Vol. III - Biological Control of Insect Pests In The Tropics - M. V. Sampaio, V. H. P. Bueno, L. C. P. Silveira and A. M. Auad BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF INSECT PESTS IN THE TROPICS M. V. Sampaio Instituto de Ciências Agrária, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brazil V. H. P. Bueno and L. C. P. Silveira Departamento de Entomologia, Universidade Federal de Lavras, Brazil A. M. Auad Embrapa Gado de Leite, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, Brazil Keywords: Augmentative biological control, bacteria, classical biological control, conservation of natural enemies, fungi, insect, mite, natural enemy, nematode, predator, parasitoid, pathogen, virus. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Natural enemies of insects and mites 2.1. Entomophagous 2.1.1. Predators 2.1.2. Parasitoids 2.2. Entomopathogens 2.2.1. Fungi 2.2.2. Bacteria 2.2.3. Viruses 2.2.4. Nematodes 3. Categories of biological control 3.1. Natural Biological Control 3.2. Applied Biological Control 3.2.1. Classical Biological Control 3.2.2. Augmentative Biological Control 3.2.3. Conservation of Natural Enemies 4. Conclusions Glossary UNESCO – EOLSS Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary SAMPLE CHAPTERS Biological control is a pest control method with low environmental impact and small contamination risk for humans, domestic animals and the environment. Several success cases of biological control can be found in the tropics around the world. The classical biological control has been applied with greater emphasis in Australia and Latin America, with many success cases of exotic natural enemies’ introduction for the control of exotic pests. Augmentative biocontrol is used in extensive areas in Latin America, especially in the cultures of sugar cane, coffee, and soybeans. -

Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) from Morocco and Comparison with North Africa Region Fauna 55 Khadija Kissayi, Souâd Benhalima and Moulay Chrif Smaili

Journal of Entomology and Nematology Volume 9 Number 7, December 2017 ISSN 2006-9855 ABOUT JEN The Journal of Entomology and Nematology (JEN) (ISSN: 2006-9855) is published monthly (one volume per year) by Academic Journals. Journal of Entomology and Nematology (JEN) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject such as applications of entomology in solving crimes, taxonomy and control of insects and arachnids, changes in the spectrum of mosquito-borne diseases etc. The Journal welcomes the submission of manuscripts that meet the general criteria of significance and scientific excellence. Papers will be published shortly after acceptance. All articles published in JEN are peer-reviewed. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/JEN Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Associate Editors Editor Dr. Sam Manohar Das Dept. of PG studies and Research Centre in Zoology, Scott Christian College (Autonomous), Prof. Mukesh K. Dhillon Nagercoil – 629 003, ICRISAT Kanyakumari District,India GT-Biotechnology, ICRISAT, Patancheru 502 324, Andhra Pradesh, Dr. Leonardo Gomes India UNESP Av. 24A, n 1515, Depto de Biologia, IB, Zip Code: Dr. Lotfalizadeh Hosseinali 13506-900, Department of Insect Taxonomy Rio Claro, SP, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection Brazil. Tehran, P. O. B. 19395-1454, Iran Dr. J. Stanley Vivekananda Institute of Hill Agriculture Prof. Liande Wang Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Almora– Faculty of Plant Protection, 263601, Uttarakhand, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University India Fuzhou, 350002, P.R. China Dr. Ramesh Kumar Jain Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Dr. -

Oystershell Scale Lepidosaphes Ulmi Order Hemiptera, Family Diaspididae; Armored Scales Native Pest

Pests of Trees and Shrubs Oystershell scale Lepidosaphes ulmi Order Hemiptera, Family Diaspididae; armored scales Native pest Host plants: Ash, beech, birch, boxwood, cotoneaster, elm, fruit trees, lilac, maple, poplar, willow, and approxi- mately 20 other species Description: Adult female covers are approximately 3 mm long, convex, oystershell-shaped and gray to brown in color. Male covers, if present, are usually smaller. Eggs and crawlers are white. Gray form of oystershell scale on maple. (183) Life history: Crawlers hatch in late May to early June Photo: John Davidson and seek suitable feeding sites on branches and trunks. Nymphs mature in mid summer to mate. Eggs are depos- ited in late summer to early fall beneath the mother’s cover. There is one generation a year; two generations in the South. Overwintering: Eggs under the cover of the dead mother scale. Damage symptoms: Damage from scale feeding causes cracked bark and chlorotic, stunted foliage. Heavy infestations can kill branches or trees or weaken them to the point of being susceptible to secondary pests such as borers. Monitoring: In Wooster, Ohio, first generation eggs hatch when black locust and multiflora rose bloom in late May. Second generation eggs hatch in mid to late July. In Midland, Michigan, first generation eggs hatch when Vanhoutte spirea and black cherry bloom in mid May, Brown form of oystershell scale with female cover removed to and there is no second generation. Look for the character- show overwintering eggs. (185) istic oystershell-shaped brown to purplish-gray scale Photo: John Davidson covers on bark. Look for wilting foliage and imminent dieback. -

Oystershell Scale

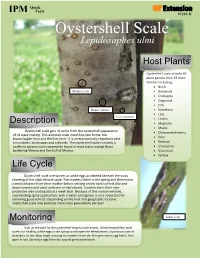

Quick IPM Facts W289-R Oystershell Scale Lepidosaphes ulmi Host Plants Oystershell scale attacks 85 plant genera from 33 plant families including: • Birch Mother scale • Boxwood • Crabapple • Dogwood • Elm Dead crawlers • Hawthorn • Lilac Live crawlers • Linden Description • Magnolia • Maple Oystershell scale gets its name from the oystershell appearance • Ornamental cherry of its waxy coating. This armored scale insect has two forms: the • brown/apple form and the lilac form. It is an economically important pest Pear in nurseries, landscapes and orchards. The oystershell scale is mainly a • Redbud northern species and is commonly found in most states except those • Smoketree bordering Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico. • Viburnum • Willow Life Cycle Oystershell scale overwinter as white eggs protected beneath the waxy covering of the adult female scale. The crawlers hatch in the spring and then move a small distance from their mother before settling on the bark to feed (live and dead crawlers and adult scale are circled above). Crawlers form their own protective wax coating about a week later. Because of this narrow window, coordinating spray applications with crawler emergence is very important for achieving good control. Depending on the host and geographic location, oystershell scale may produce one to two generations per year. Monitoring Adult scale Look on the bark for the oystershell-shaped scale covers. Check beneath the scale covers for healthy, white eggs in the spring to estimate the effectiveness of previous control strategies. In late May, begin scouting for crawlers from the first-generation egg hatch, then again in late July when eggs from the second generation hatch. -

Bionomics of Chilocorus Infernalis Mulsant, 1853 (Coleoptera

doi:10.14720/aas.2019.113.1.07 Original research article / izvirni znanstveni članek Bionomics of Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853 (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), a predator of San Jose scale, Diaspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock, 1881) under laboratory conditions Razia RASHEED1*, A.A. BUHROO1 and Shaziya GULL1 Received July 23, 2018; accepted January 03, 2019. Delo je prispelo 23. julija 2018, sprejeto 03. januarja 2019. ABSTRACT IZVLEČEK The bionomics of Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853, a BIONOMIJA VRSTE Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853 natural enemy of San Jose scale, was studied under laboratory (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), PLENILCA AMERIŠKEGA conditions (26 ± 2˚C, and 65 ± 5% relative humidity). The KAPARJA (Diaspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock, 1881)) V eggs were deposited in groups and on average 45.68 ± 24.70 LABORATORIJSKIH RAZMERAH eggs were laid by female. Mean observed incubation period was 6.33 ± 1.52 days. Four instar grubs were observed, and Bionomija vrste Chilocorus infernalis Mulsant, 1853, mean duration of all four grubs was found to be 19.98 days. naravnega sovražnika ameriškega kaparja, je bila preučevana The pupal stage lasted for 8.00 ± 0.50 days and after adults v laboratorijskih razmerah (26 ± 2˚C in 65 ± 5 % relativne emerged out. zračne vlažnosti). Samice plenilca so jajčeca odlagale v skupinah, v poprečju 45,68 ± 24,70 jajčec na samico. V Key words: bionomics; natural enemies; San Jose scale; povprečju so se ličinke razvile iz jajčec v 6,33 ± 1,52 dneh. incubation period; larval instars Ugotovljene so bile štiri larvalne stopnje, katerih povprečna življenska doba je bila 19,98 dni. Razvojni štadij bube je trajal 8,00 ± 0,50 dni, nakar so se izlegli imagi. -

Catalog of the Encarsia of the World (2007)

Catalog of the Encarsia of the World (2007) John Heraty, James Woolley and Andrew Polaszek (a work in progress) Note: names in parentheses refer to species groups, not subgenera. Encarsia Foerster, 1878. Type species: Encarsia tricolor Foerster, by original designation. Aspidiotiphagus Howard, 1894a. Type species: Coccophagus citrinus Craw, by original designation. Synonymy by Viggiani & Mazzone, 1979[144]: 44. Aspidiotiphagus Howard, 1894a. Type species: Coccophagus citrinus Craw, by original designation. Synonymy by Viggiani & Mazzone, 1979[144]: 44. Prospalta Howard, 1894b. Type species: Coccophagus aurantii Howard. Subsequently designated by ICZN, Opinion 845, 1968: 12-13. Homonym; discovered by ??. Encarsia of the World 2 Prospalta Howard, 1894b. Type species: Coccophagus aurantii Howard. Homonym of Prospalta Howard; discovered by ??. Encarsia; Howard, 1895b. Subsequent description. Prospaltella Ashmead, 1904[238]. Replacement name; synonymy by Viggiani & Mazzone, 1979[144]: 44. Prospaltella Ashmead, 1904[238]. Replacement name for Prospalta Howard Viggiani & Mazzone, 1979[144]: 44. Mimatomus Cockerell, 1911. Type species: Mimatomus peltatus Cockerell, by monotypy. Synonymy by Girault, 1917[312]: 114. Doloresia Mercet, 1912. Type species: Prospaltella filicornis Mercet, by original designation. Synonymy by Mercet, 1930a: 191. Aspidiotiphagus; Mercet, 1912a. Subsequent description. Encarsia; Mercet, 1912a. Subsequent description. Prospaltella; Mercet, 1912a. Subsequent description. Prospaltoides Bréthes, 1914. Type species: Prospaltoides -

Life-History Parameters of Encarsia Formosa, Eretmocerus Eremicus and E

Eur. J. Entomol. 101: 83–94, 2004 ISSN 1210-5759 Life-history parameters of Encarsia formosa, Eretmocerus eremicus and E. mundus, aphelinid parasitoids of Bemisia argentifolii (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) YU TONG QIU, JOOP C. VAN LENTEREN, YVONNE C. DROST and CONNIE J.A.M. POSTHUMA-DOODEMAN Laboratory of Entomology, Wageningen University; P.O.Box 8031, 6700 EH Wageningen, The Netherlands e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Key words. Hymenoptera, Aphelinidae, Homoptera, Aleyrodidae, whiteflies, Encarsia formosa, Eretmocerus eremicus, Eretmocerus mundus, biological control, life history, longevity, development time Abstract. Life-history parameters (juvenile development time, adult longevity, host instar preference and rate of parasitism) of four parasitoids of Bemisia argentifolii (two strains of Encarsia formosa (D and B), Eretmocerus eremicus and Eretmocerus mundus) were studied in the laboratory. At 15°C juvenile development time was the shortest for E. formosa B (48 days), longest for E. ere- micus (79.3 days) and intermediate for E. formosa D (62.8 days) and E. mundus (64 days) at 15°C. With increase in temperature, development time decreased to around 14 days for all species/strains at 32°C. The lower developmental threshold for development was 11.5, 8.1, 13.0 and 11.5°C for E. formosa D, E. formosa B, E. eremicus and E. mundus, respectively. E. formosa D and B, and E. mundus all appeared to prefer to parasitize 3rd instar nymphs. The presence of hosts shortened adult longevity in most of the para- sitoids, with the exception of E. formosa B, which lived longer than other species/strains irrespective of the presence of hosts. -

The Occurrence of Encarsia Perniciosi in Areas of Northern Greece As Assessed by Sex Pheromone Traps of Its Host Quadraspidiotus Perniciosus'

ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA S (1987): 7-12 The Occurrence of Encarsia perniciosi in Areas of Northern Greece as Assessed by Sex Pheromone Traps of its Host Quadraspidiotus perniciosus' D.S. KYPARISSOUDAS Plant Protection Service of Thessaloniki, GR-54626 Thessaloniki, Greece ABSTRACT During the 1982-1985 period the aphelinid endoparasite Encarsia perniciosi Tower was cap tured on synthetic pheromone traps of the San Jose scale (SJS), Quadraspidiotus pernicio sus Comstock, in scale-infested insecticide treated and untreated orchards of Central and Western Macedonia (Northern Greece). It has expanded especially near the sites where it had been released, but also in areas 50-100 km from the point of release. The parasite in untreated orchards generally appeared from April to October, while in orchards treated with insecticides it was not caught after mid June. Spring flights of the parasite occurred on almost the same dates as the first captures of the male scale. Subsequent flights of E. perni ciosi were not always synchronized with those of the male scale, and after the beginning of June the parasite showed a general decline throughout the remainder of each season. The pheromone of the scale insect acts as a kairomone to the parasite and it can be used in trapping systems in scale-infested orchards for the confirmation of the presence and the dis tribution of E. perniciosi. Introduction riou 1985). In 1982, in a study on the flight of the SJS males by means of synthetic sex pheromone Encarsia perniciosiTower (Hymenoptera: Aphe- traps (Zoëcon's type «tent») we observed that be linidae) is a monophagus, solitary endoparasite of sides SJS males, its parasite E.