The Periodical Cicada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsatellite Loci Isolated from the Mediterranean Species Cicada Barbara (Stål) and C

Molecular Ecology Notes (2002) 2, 173–175 PRIMERBlackwell Science, Ltd NOTE Microsatellite loci isolated from the Mediterranean species Cicada barbara (Stål) and C. orni L. (Hemiptera, Cicadoidea) S. G. SEABRA,*† H. R. WILCOCK,* J. A. QUARTAU† and M. W. BRUFORD* *School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3TL, UK, †Centro de Biologia Ambiental e Departamento de Zoologia e Antropologia, Bloco C2, 3° Piso, Faculdade de Ciências de Lisboa, Campo Grande 1700 Lisboa, Portugal Abstract We describe the isolation of six polymorphic microsatellites for Cicada barbara (Stål), four of which are also polymorphic for the closely related Cicada orni L. Cicadas from several sites in the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa (C. barbara) and Greece (C. orni) were genotyped at these loci. Polymorphism is higher than that previously obtained with allozymes for these species. One locus allows species diagnosis (nonoverlapping allele size ranges) between C. barbara and C. orni and the others have some exclusive alleles for each species. Keywords: cicadas, Cicada barbara, Cicada orni, insects, microsatellites Received 6 November 2001; revision received 21 December 2001; accepted 21 December 2001 The genus Cicada L. (Hemiptera, Cicadoidea) includes agarose gel by electroelution into dialysis tubing and some sibling species that are morphologically very similar purified using Centricon Microconcentrators (Amicon). but distinguishable by the specific calling songs produced The fragments were enriched for CA and GA repeats using by males for mate recognition. Cicada barbara and C. orni are biotin-labelled probes and then ligated into a pUC18 vector two of these species that exist in sympatry in some areas (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) (Hammond et al. -

Summer Concert Series: Nature's Symphony

Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org ribbit chirp chirp Seasonal Sightings Environmental Adventures The buzzzz Whether it’s chirping chipmunks, singing birds, or calling katydids, Sounds of one thing is for sure—sounds will abound this summer in Conservation Summer Concert Series: District sites. It’s easy to experience the chorus. Just head to one of our Summer 32 sites and venture out onto the trails. Try the activities below, and Nature’s Symphony listen to as many nature sounds as you can this summer. by Kim Compton, Education Program Coordinator Broadwinged katydid The beauty of nature is well Can you make these animal sounds? documented – with scenic vistas, photographs, and paintings; but Snowy tree cricket Run your finger down the teeth Clemson University–USDA Cooperative Extension have you ever really stopped Slide Series, Bugwood.org of a comb to make a sound like a chorus frog call. to listen to nature? A veritable symphony of sounds greets us every time we venture out into the great Rub two pieces of sandpaper outdoors. Summertime is an especially musical time. together to make a sound American tree sparrow like a grasshopper calling. Bob Williams Bob Birds can have harsh down or speeds up based on calls, sweet songs, and everything in between. Visit the the temperature. This means wetlands to hear the ever-present “conk-a-reeeee” call of we can try to approximate the the red-winged blackbird. You may also be rewarded with a evening temperature by listening suddenly loud and resonating cry of a nesting sandhill crane to cricket chirps! The Farmer’s MAKE A SOUND MAP! or the almost-maniacal whinny of the seldom seen sora rail. -

Insects That Glow and Sing

IInsectsnsects ThatThat GGlowlow aandnd SSinging 6 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Classify and identify insects as small six-legged animals with three body parts Identify and describe the three body parts of insects: head, thorax, and abdomen Identify the placement and/or purpose of an insect’s body parts Describe an insect’s exoskeleton Compare and contrast grasshoppers and crickets Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Plan, draft, and edit an informative text that presents information about insects, including an introduction to a topic, relevant facts, and a conclusion (W.2.2) Participate in a shared research project on insects (W.2.7) With assistance, categorize and organize facts and information from “Insects That Glow and Sing” (W.2.8) Generate questions and gather information from multiple sources to answer questions about insects (W.2.8) Add drawings to descriptions of f ref ies, grasshoppers, and crickets to clarify ideas, thoughts, and feelings (SL.2.5) 82 Insects 6 | Insects That Glow and Sing © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Use the antonyms transparent and opaque appropriately in oral language (L.2.5a) Prior to listening to “Insects That Glow and Sing,” identify orally what they know and have learned about insects Use adverbs correctly in oral language Core Vocabulary bioluminescence, n. Light given off by some plants and animals, such as f ref ies, caused by a biochemical reaction Example: The night sky was f lled with the bioluminescence of dancing f ref ies. -

Efficacy of New Insecticide Molecules Against Major Predatory Insects in Kusmi Lac

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(12): 100-106 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 12 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.712.013 Efficacy of New Insecticide Molecules against Major Predatory Insects in Kusmi Lac Savita Aditya and S.P. Singh* Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Raigarh-496001, India Indira Gandhi Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Raipur (C.G.), India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT The study was carried out for the assessment of abundance of predatory insects associated K e yw or ds with lac insect Kerria lacca (Kerr) and their management through new insecticide molecule in kusmi lac during July-October 2015-16 and 2016-17. A combination of Kusmi lac, Kerria lacca, Emamectin benzoatate 5 % SG +Carbendazim 50 WP (T ), Indoxacarb 14.5 % SC + 1 Natural enemies of lac crop, New insecticide Carbendazim 50 WP (T2) and Control (T3) was evaluated against the predators of the lac molecule insect. Pesticides application significantly reduced the incidence of major predators Eublemma amabilis Moore and Pseudohypatopa pulverea Mayr in comparison to (T ). Article Info 3 There was a reduction in the population of predatory insects 81.97 per cent in T and 77.78 1 Accepted: per cent T2 respectively over the year. It was seen that the different samples of lac 04 November 2018 collected from different lac growing areas of Chhattisgarh and noted that not a single Available Online: sample was free from the attack of predator Eublemma amabilis Moore and 10 December 2018 Pseudohypatopa pulverea Mayr and appeared as major problem of lac host plants and losses consideration level in most of the areas. -

AND BODY of CICADA": IMPRESSIONS of the LANTERN-FLY (HEMIPTERA: FULGORIDAE) in the VILLAGE of Penna BRANCA" BAHIA STATE, BRAZIL

Journal of Ethnobiology 23-46 SpringiSummer 2003 UHEAD OF SNAKE, WINGS OF BUTTERFL~ AND BODY OF CICADA": IMPRESSIONS OF THE LANTERN-FLY (HEMIPTERA: FULGORIDAE) IN THE VILLAGE OF PEnnA BRANCA" BAHIA STATE, BRAZIL ERALDO MEDEIROS COSTA-NElO" and JOSUE MARQUES PACHECO" a Departtll'rtl?nto de Cit?t1Cias BioMgicasr Unh:rersidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Km 3, BR 116, Campus Unirl£rsitario, eEP 44031-460, Ferra de Santana, Bahia, Brazil [email protected],br b DepartmHemo de Biowgifl Evolutim e Ecologia, Unit:rersidade Federal de Rod. Washington Luis, Km 235, Caixa Postal 676, CEP 13565~905, Sao Silo Paulo, Brazil r:~mail: [email protected] To the memory of Darrell Addison Posey (1947-2001) ABSTRACT.-Four aspects of the ethnoentomology of the lantern-fly (Fulgora la temari" L., 1767) were studied in Pedra Branca, Brazil. A total of 45 men and 41 women were consulted through open-ended interviews and their actions were observed in order to document the wisdom, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to the lantern-fly. People/s perceptions of the ex.temal shape of the insect influence its ethnotaxonomy, and they may categorize it into five different ethnosemantic domains, VilJagers a.re familiar with the habitat and food habits of the lantern- fly; they it lives on the trunk of Simarouba sp. (Simaroubaceae} by feeding on sap with aid of its 'sting: The culturally constructed attil:tldes toward this insect are that it is a fearsome organism that should be extlimninated .vhenever it is found because it makes 'deadly attacks.' on plants and human beings. -

Locusts in Queensland

LOCUSTS Locusts in Queensland PEST STATUS REVIEW SERIES – LAND PROTECTION by C.S. Walton L. Hardwick J. Hanson Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the many people who provided information for this assessment. Clyde McGaw, Kevin Strong and David Hunter, from the Australian Plague Locust Commission, are also thanked for the editorial review of drafts of the document. Cover design: Sonia Jordan Photographic credits: Natural Resources and Mines staff ISBN 0 7345 2453 6 QNRM03033 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Mines, Qld. February 2003 Information in this document may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, provided that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Land Protection Department of Natural Resources and Mines GPO Box 2454, Brisbane Q 4000 #16401 02/03 Contents 1.0 Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Taxonomy.................................................................................................................. 2 3.0 History ....................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Outbreaks across Australia ........................................................................................ 3 3.2 Outbreaks in Queensland........................................................................................... 3 4.0 Current and predicted distribution ........................................................................ -

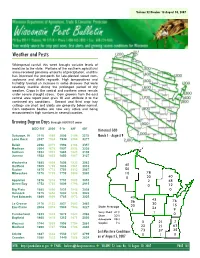

Weather and Pests

Volume 52 Number 18 August 10, 2007 Weather and Pests Widespread rainfall this week brought variable levels of moisture to the state. Portions of the southern agricultural areas received generous amounts of precipitation, and this has improved the prospects for late-planted sweet corn, soybeans and alfalfa regrowth. High temperatures and humidity favored an increase in some diseases that were relatively inactive during the prolonged period of dry weather. Crops in the central and northern areas remain under severe drought stress. Corn growers from the east central area report poor grain fill and attribute it to the continued dry conditions. Second and third crop hay cuttings are short and yields are generally below normal. Corn rootworm beetles are now very active and being encountered in high numbers in several counties. Growing Degree Days through 08/09/07 were GDD 50F 2006 5-Yr 48F 40F Historical GDD Dubuque, IA 2115 1989 2006 2194 3379 March 1 - August 9 Lone Rock 2037 1924 1934 2058 3277 Beloit 2098 2071 1996 2106 3357 Madison 2004 1879 1907 2028 3236 Sullivan 1932 1912 1883 1923 3139 Juneau 1922 1803 1850 1967 3127 Waukesha 1885 1804 1806 1933 3083 Hartford 1909 1789 1803 1961 3010 40 50 Racine 1875 1774 1751 1912 3067 Milwaukee 1870 1785 1739 1906 3063 10 78 20 40 0 Appleton 1876 1818 1731 1909 3051 2 48 Green Bay 1752 1703 1609 1798 2915 0 12 Big Flats 1885 1890 1831 1846 3058 0 Hancock 1875 1858 1802 1836 3026 Port Edwards 1869 1899 1765 1873 3035 43 45 36 76 La Crosse 2178 2133 2037 2063 3462 30 20 15 Eau Claire 2004 2078 1903 1982 3227 State Average 24 9 Very Short 41% 1 Cumberland 1833 1828 1679 1822 2986 1 0 Short 32% Bayfield 1465 1478 1312 1471 2500 Adequate 26% 5 2 Wausau 1744 1689 1598 1754 2861 Surplus 1% 21 Medford 1690 1707 1568 1708 2804 22 21 63 35 Soil Moisture Conditions 73 57 Crivitz 1687 1638 1530 1727 2799 0 0 1 Crandon 1588 1522 1449 1568 2634 as of August 5, 2007 WEB: http://pestbulletin.wi.gov z EMAIL: [email protected] z VOLUME 52 Issue No. -

Teachers Resources

TEACHERS RESOURCES 1 CICADA BY SHAUN TAN Teachers Resources by Robyn Sheahan-Bright Introduction 4 Before and After Reading the Picture Book 5 Themes 5 Curriculum Topics 8 Study of History, Society and Environment English Language and Literacy Visual Literacy Creative Arts Learning Technologies Further Extension Activities 14 Further Topics for Discussion and Research 15 Conclusion 15 2 Author/Illustrator’s Inspiration 15 About the Author/Illustrator 19 Activity Sheets 21 Bibliography 24 About the Author of the Notes 26 3 INTRODUCTION Cicada tell story. Story good. Story simple. Story even human can understand. Tok Tok Tok! Back Cover Text Cicada has worked for the company for seventeen years – always finishes work perfectly; does unpaid overtime; is never offered promotion; has no access to office bathroom; sleeps in office wallspace; humans don’t like cicada; told to retire; climbs to top of building and ... This stunning open-ended text is a philosophical exploration of the culture of work but also of society. It traverses themes such as belonging, alien- ation, corporate bureaucracy and work, difference and prejudice, sub- mission to control/freedom, transformation/metamorphosis, resurrection and regeneration. Shaun Tan’s publisher describes the book as: ‘A dream of escape, a com- mentary on corporate slavery, a multi-layered allegory—Shaun has taken the humble cicada and created a mythic fairytale of magic, menace and wonder.’ Justin Ratcliffe, co-managing Director, Hachette B&P 15 November 2017 Shaun Tan is partly concerned here with Kafka’s nightmare of bureaucra- cy which, like many other concepts swirls together in a tantalising soup of ideas. -

Potential Impact of Desert Locust to Nutrition Security in SOMALIA

POTENTIAL IMPACT OF DESERT LOCUST Emma Apo Ouma TO NUTRITION SECURITY IN SOMALIA WHAT IS THE CURRENT SITUATION? •Triple threat of Desert Locust, Gu flooding and COVID-19, •April and June 2020, an estimated 2.7 million people across Somalia are expected to face Crisis and deteriorate to 3.5 million between July and September 2020 WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR NUTRITION SECURITY? CROP AND PASTURE DAMAGE Threat to current Gu season crop production and may also threaten pasture availability and crop cultivation across Somalia through the following 2020 Deyr (October-December A swarm can eat enough food in one day to feed 34 million people. FALLING LIVESTOCK PRICES •Livestock diseases •Poor livestock nutrition; increased price of livestock feed •Reduced quality of livestock products eg milk, meat LOSS OF LIVELIHOODS •Disruption of food systems; critical value chains have been affected e.g. livestock, cereals such as sorghum, maize •Loss of wage and employment opportunities e.g. labor in the fields, value chain actors •Increase in livelihood based coping strategy: eg selling last breeding animal, spent savings, begging, reduced expenditure on livestock and agriculture •Reduced spending on non-food needs health care, education FOOD CONSUMPTION AND DIETARY DIVERSITY •With poor harvests, there is likelihood of poor food consumption at hhd level •Depletion of food stocks •Food Prices have increased •A majority if households rely on markets for food: increased reliance on purchased and processed foods •Compromise the nutrition of the most vulnerable: children less than 5, PLW, elderly, adolesents •Increased rates of acute malnutrition ONGOING EFFORTS Household Level Screening and referral of acute malnutrition cases Targeting of the most vulnerable (UCT) Community level ▪Burying locusts, setting fires, and making noise to scare them off. -

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

Rapid and Simple Species Identification of Cicada Exuviae

insects Article Rapid and Simple Species Identification of Cicada Exuviae Using COI-Based SCAR Assay Pureum Noh, Wook Jin Kim, Jun-Ho Song , Inkyu Park , Goya Choi and Byeong Cheol Moon * Herbal Medicine Resources Research Center, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Naju 58245, Korea; [email protected] (P.N.); [email protected] (W.J.K.); [email protected] (J.-H.S.); [email protected] (I.P.); [email protected] (G.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-61-338-7100 Received: 5 February 2020; Accepted: 4 March 2020; Published: 6 March 2020 Abstract: Cicadidae periostracum (CP), the medicinal name of cicada exuviae, is well-known insect-derived traditional medicine with various pharmacological effects, e.g., anticonvulsive, anti-inflammatory, antitussive, and anticancer effects; it is also beneficial for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. For appropriate CP application, accurate species identification is essential. The Korean pharmacopoeia and the pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China define Cryptotympana atrata as the only authentic source of CP. Species identification of commercially distributed CP based on morphological features, however, is difficult because of the combined packaging of many cicada exuviae in markets, damage during distribution, and processing into powder form. DNA-based molecular markers are an excellent alternative to morphological detection. In this study, the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I sequences of C. atrata, Meimuna opalifera, Platypleura kaempferi, and Hyalessa maculaticollis were analyzed. On the basis of sequence alignments, we developed sequence-characterized amplified-region (SCAR) markers for efficient species identification. These markers successfully discriminated C. -

Lesson 3 Life Cycles of Insects

Praying Mantis 3A-1 Hi, boys and girls. It’s time to meet one of the most fascinating insects on the planet. That’s me. I’m a praying mantis, named for the way I hold my two front legs together as though I am praying. I might look like I am praying, but my incredibly fast front legs are designed to grab my food in the blink of an eye! Praying Mantis 3A-1 I’m here to talk to you about the life stages of insects—how insects develop from birth to adult. Many insects undergo a complete change in shape and appearance. I’m sure that you are already familiar with how a caterpillar changes into a butterfly. The name of the process in which a caterpillar changes, or morphs, into a butterfly is called metamorphosis. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 Insects like the butterfly pass through four stages in their life cycles: egg, larva [LAR-vah], pupa, and adult. Each stage looks completely different from the next. The young never resemble, or look like, their parents and almost always eat something entirely different. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 The female insect lays her eggs on a host plant. When the eggs hatch, the larvae [LAR-vee] that emerge look like worms. Different names are given to different insects in this worm- like stage, and for the butterfly, the larva state is called a caterpillar. Insect larvae: maggot, grub and caterpillar3A-3 Fly larvae are called maggots; beetle larvae are called grubs; and the larvae of butterflies and moths, as you just heard, are called caterpillars.