'Sepia, Camouflage, Modernity'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Tucson Art Academy Online Skip Whitcomb

TUCSON ART ACADEMY ONLINE SKIP WHITCOMB PAINTS WHITE Any good to professional quality Titanium or Titanium/Zinc White in large tubes(150-200ML) size. Jack Richeson Co., Gamblin, Vasari, Utrecht, Winsor & Newton are all good brands, as are several other European manufacturers. I strongly recommend staying away from student grade paints, they do not mix or handle the same as higher/professional grade paints. YELLOWS Cadmium Yellow Lemon Cadmium Yellow Lt. (warm) Cad. Yellow Medium or Deep Indian Yellow ORANGES Cadmium Yellow Orange (optional) Cadmium Orange REDS Cadmium Red Light/ Pale/ Scarlet (warm) Cadmium Red Deep Permanent Alizarin Crimson Permanent Rose (Quinacridone) BLUES Ultramarine Blue Deep or Dark Cobalt Blue Prussian Blue or Phthalo Blue GREENS Viridian Viridian Hue (Phthalo Green) Chrome Oxide Green Olive Green Sap Green Yellow Green VIOLETS Mauve Blue Shade (Winsor&Newton) Dioxazine Violet or Purple EARTH COLORS Yellow Ochre Raw Sienna Raw Umber Burnt Sienna Terra Rosa Indian Red Venetian Red Burnt Umber Van Dyke Brown BLACKS Ivory Black Mars Black Chromatic Black Blue Black MARS COLORS Mars Yellow Mars Orange Mars Red Mars Violet IMPORTANT TO NOTE!! Please don’t be intimidated by this list! You will not be required to have all these colors on hand for our class. This is intended to be a recommendation for the studio. Specific colors on this list will come in handy for mixing in certain color plans. I will be happy to make suggestions along the way A good working palette for the studio would be: Cad. Yellow Lemon, Cad. Yellow Pale(warm), and/or Cad. -

Derivan Matisse Flow to Americana Acrylics Color Conversion Chart

Derivan Matisse Flow to Americana Acrylics Color Conversion Chart Derivan Americana Derivan Americana Matisse Flow Acrylics Matisse Flow Acrylics Alpine Green 2 - DAO82 Evergreen Brilliant Alizarine 2 - DA179 Alizarin Crimson 1 - DA144 Yellow Light 1 - DA159 Cherry Red Antique Blue 1 - DAO38 Wedgewood Blue Burgundy 1 - DA140 Red Violet 1 - DA166 Deep Midnight Blue 1 - DA165 Napa Red 1 - DA172 Black Plum Antique Gold 1 - DA146 Antique Gold Deep Burnt Sienna DA223 Traditional Burnt Sienna ato - DAO67 Lamp (Ebony) Black Antique Green 2 - DA105 Blue Grey Mist Burnt Umber 2 - DA221 Traditional Burnt Umber 1 - DAO84 Midnite Green 1 - DA160 Antique Maroon Antique White 2 - DA239 Warm White Cadmium Orange 8 - DA228 Bright Orange 1 - DAO3 Buttermilk 1 - DAO10 Cadmium Yellow Aqua Green Light 2 - DAO1 Snow (Titanium) White Cadmium Red Medium DAO15 Cadmium Red 1 - DAO47 Bluegrass Green Ash Pink 4 - DA164 Light Buttermilk Cadmium Yellow Light DA144 Yellow Light 3 - DA189 Summer Lilac 2 - DA186 French Mauve Aureolin Yellow 4 - DA144 Yellow Light Cadmium Yellow Medium DA227 Bright Yellow 1 - DA146 Antique Gold Deep 1 - DAO10 Cadmium Yellow Australian Olive Green 10 - DA113 Plantation Pine Carbon Black DAO67 Lamp (Ebony) Black 1 - DAO67 Lamp (Ebony) Black Australian Red Violet DA140 Red Violet Cerulean Blue DAO36 True Blue Australian Sap Green 2 - DA113 Plantation Pine Chromium Green Oxide 2 - DAO51 Leaf Green 1 - DA144 Yellow Light 1 - DAO53 Mistletoe Australian Sienna 1 - DA223 Traditional Burnt Sienna Cobalt Blue 2 - DA141 Blue Violet 1 - DA194 Marigold -

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary

ELOISE BUTLER WILDFLOWER GARDEN AND BIRD SANCTUARY WEEKLY GARDEN HIGHLIGHTS Phenology notes for the week of October 5th – 11th It’s been a relatively warm week here in Minneapolis, with daytime highs ranging from the mid-60s the low 80s. It’s been dry too; scant a drop of rain fell over the past week. The comfortable weather was pristine for viewing the Garden’s fantastic fall foliage. Having achieved peak color, the Garden showed shades of amber, auburn, beige, blond, brick, bronze, brown, buff, burgundy, canary, carob, castor, celadon, cherry, cinnabar, claret, clay, copper, coral, cream, crimson, ecru, filemont, fuchsia, gamboge, garnet, gold, greige, khaki, lavender, lilac, lime, magenta, maroon, mauve, meline, ochre, orange, peach, periwinkle, pewter, pink, plum, primrose, puce, purple, red, rose, roseate, rouge, rubious, ruby, ruddy, rufous, russet, rust, saffron, salmon, scarlet, sepia, tangerine, taup, tawny, terra-cotta, titian, umber, violet, yellow, and xanthic, to name a few. According to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the northern two thirds of the state reached peak color earlier in 2020 than it did in both 2019 and 2018, likely due to a relatively cool and dry September. Many garter snakes have been seen slithering through the Garden’s boundless leaf litter. Particularly active this time of year, snakes must carefully prepare for winter. Not only do the serpents need to locate an adequate hibernaculum to pass the winter, but they must also make sure they’ve eaten just the right amount of food. Should they eat too little, they won’t have enough energy to make it through the winter. -

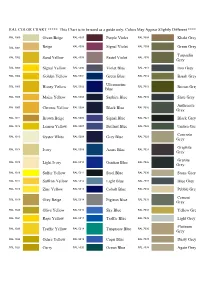

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

E'tac EFX Series Color Wheel TINT

E’TAC EFX series EFX 507 Dark naphtol red EFX 506 Naphtol red color wheel TINT EFX 509 Quina magenta EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 507 Dark naphtol red © Eddy & Marissa Wouters http://www.etac-airbrush.com http://www.etac-europe.com EFX 506 Naphtol red EFX 512 Red violet EFX 516 Red ocher EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 510 Carbazole violet EFX 505 Azo orange EFX 516 Red ocher EFX 511 Blue violet EFX 517 Brown ocher EFX 505 Azo orange EFX 517 Brown ocher EFX 525 Flesh EFX 525 Flesh EFX 518 Burnt umber EFX 526 Ultramarine blue EFX 518 Burnt umber EFX 519 Culebra gold EFX 504 Golden ocher EFX 523 Sepia smoke HOT colors EFX 503 Arylide yelow EFX 522 Rainforest green EFX 519 EFX 524 Gray Culebra gold EFX 514 Phthalo green EFX 520 Vieques blue EFX 513 Phthalo blue COOL colors EFX 515 Phthalo turquoise EFX 521 Aqua rica EFX 504 EFX 521 Aqua rica Golden ocher EFX 513 Phthalo blue EFX 515 Phthalo turquoise EFX 526 Ultramarine blue EFX 520 Vieques blue EFX 503 Arylide yelow EFX 511 Blue violet EFX 510 Carbazole violet EFX 512 Red violet EFX 514 Phthalo green EFX501 HS Carbon black EFX 522 Rainforest green EFX 509 Quina magenta EFX 524 Gray COOL HOT colors colors EFX502 OT Plasma white EFX 523 Sepia smoke E’TAC EFX series EFX 507 Dark naphtol red EFX 506 Naphtol red Color wheel TONE EFX 509 Quina magenta EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 507 Dark naphtol red © Eddy & Marissa Wouters http://www.etac-airbrush.com http://www.etac-europe.com EFX 506 Naphtol red EFX 512 Red violet EFX 516 Red ocher EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 510 Carbazole violet EFX 505 Azo orange EFX 516 Red -

Brochure Old Holland Classic Oil Colours Drying Time & Transparency

Old Holland Classic Oil Colours Drying time & Transparency Transparency: * = Transparent **** = Opaque Drying time: F = Fast, M = Medium, S = Slow Oil content: H = High, M = Medium, L = Low, VL = Very Low Colour name Colour index Pigment classification Trans- light- Drying Oil parency fastness time content A1 Titanium white PW6 Titanium dioxide **** 7/8 m l A2 Zinc white PW4 Zinc oxide *** 7/8 m l 3 Lead white PW1 Basic lead carbonate **** 7/8 f vl 4 Flake white no.1 PW1-PW4 Basic lead carbonate zinc oxide **** 7/8 m vl A5 Mixed white no.2 PW6-PW4 Titanium dioxide- zinc oxide **** 7/8 m l A6 Old Holland yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Natural ochre **** 7/8 m l light PY43 B8 Old Holland yellow PW4-PW6-PY- Zinc oxide-titanium dioxide-mono.azo-Natural ochre **** 7/8 m l deep 74-PY43 B7 Old Holland yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide-titanium dioxide-monoazo-Natural ochre *** 7/8 m l medium PY74-PY43 B103 Brilliant yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Disazo- Diketo pyrollo *** 7/8 m l light PY83-PO73 pyrrole B106 Brilliant yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Nickel titanate- Diketo- **** 7/8 m l PY53-PO73 Pyrrolo- Pyrolle B109 Brilliant yellow- PW4-PW6- Zinc white- Titanium dioxide- Nickel titanate- Diketo- **** 7/8 m l reddish PY53-PO73 Pyrrolo- Pyrolle B112 Napels yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Nickel titanate- Disazo **** 7/8 m l reddish extra PY53-PO43 B115 Flesh tint PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Zinc iron oxide- *** 7/8 m l PY119-PR2 Condensed azo B118 Indian yellow- PY95-PY129 Azo condensation- -

9789004165403.Pdf

The Arabic Manuscript Tradition Supplement Handbook of Oriental Studies Section 1, The Near and Middle East Editors H. Altenmüller B. Hrouda B.A. Levine R.S. O’Fahey K.R. Veenhof C.H.M. Versteegh VOLUME 95 The Arabic Manuscript Tradition A Glossary of Technical Terms and Bibliography – Supplement By Adam Gacek LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gacek, Adam. The Arabic manuscript tradition : a glossary of technical terms and bibliography : supplement / by Adam Gacek. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, the Near and Middle East) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16540-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Manuscripts, Arabic—History—Bibliography. 2. Codicology—Dictionaries. 3. Arabic language—Dictionaries—English. 4. Paleography, Arabic—Bibliography. I. Title. II. Series. Z6605.A6G33 2001 Suppl. 011'.31—dc22 2008005700 ISSN 0169–9423 ISBN 978 90 04 16540 3 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS CONTENTS Transliteration table ....................................................................... -

Shifting Sands of Writing Inks in Yemen. the Occurrence of Sparkling

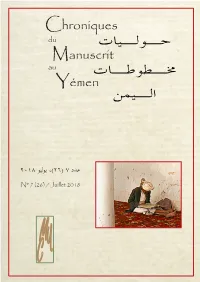

Chroniques du Manuscrit au Yémen عدد ٧ )٢٦(، يوليو ٢٠١۸ N° 7 (26) / Juillet 2018 Directrice de la Publication Anne REGOURD Contact Secrétariat [email protected] Comité de rédaction Tamon BABA (Université de Kyushu, Japon), Jan THIELE (Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid), Anne REGOURD Revue de presse Maxim YOSEFI (Université de Göttingen) Conseil de rédaction Geoffrey KHAN (Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Université de Cambridge (GB)), Martha M. MUNDY (The London School of Economics and Political Science, Dépt d’anthropologie), Jan RETSÖ (Université de Gothenburg, Dépt de langues et littératures, Suède), Sabine SCHMIDTKE (Institute for Ad- vanced Study, Princeton) Correspondants Tamon BABA (Université de Kyushu, Japon), Deborah FREEMAN-FAHID (FRAS, Assistant Con- servateur, Dir. de publication, The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Koweït), Stéphane IPERT (Res- ponsable Préservation & Conservation, Qatar National Library), Abdullah Yahya AL SURAYHI (Manuscrits, Université d’Abu Dhabi, Bibliothèque nationale, Abu Dhabi) Comité de lecture Hassan F. ANSARI (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton), Anne K. BANG (Université de Bergen, Norvège), Marco DI BELLA (Indépendant, Conservation/restauration manuscrits arabes), Deborah FREEMAN- FAHID (FRAS, Assistant Conservateur, Dir. de publication, The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Ko- weït), David G. HIRSCH (Advisor for Library Services, Mohammed bin Rashid Library, Dubai), Michaela HOFFMANN- -

Everything In

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2020-01-01 Everything In Greg Chavez University of Texas at El Paso Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Chavez, Greg, "Everything In" (2020). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 3149. https://scholarworks.utep.edu/open_etd/3149 This is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVERYTHING IN GREG CHAVEZ Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: Sylvia Aguilar-Zéleny, MH, MFA, Chair Jeffrey Sirkin, Ph.D. Annika Mann, Ph.D. Stephen L. Crites, Jr., Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Greg Chavez 2020 EVERYTHING IN by GREG CHAVEZ, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Department of Creative Writing THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2020 Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincerest gratitude for the entire creative writing community at UTEP. Your invaluable feedback and encouragement along the way has helped guide my writing into and out of spaces it had feared to tread. Special thanks to all my UTEP professors who challenged me to see writing and literature from perspectives never imagined. To my thesis committee, Professor Sylvia Aguilar-Zéleny, Dr. Jeffrey Sirkin, and Dr. -

Color Chart Includes Those Colors Made from Inorganic Pigments, That Is, Metal Ores Dug from the Earth

GAMBLIN ARTISTS COLORS GAMBLIN ARTISTS OIL COLORS Artists Oil mineral inorganic colors modern organic colors Colors • All colors made from metals (Cadmium, Cobalt, Iron, etc.) are “inorganic” • Carbon based pigments are “organic” • 19th century colors of the Impressionists and the colors of Classical and Renaissance era painters • 20th century colors • High pigment load, low oil absorption • Most pigments available in a warm and cool version (ex. Phthalo Green, Phthalo Emerald) • Colors easily grey-down in mixtures, excellent for painting natural colors and light • Best choice for high key painting, bright tints • Mostly opaque with a few semi-transparent and transparent colors • Mostly transparent, with some semi-transparent colors Impressionist 20th Century CADMIUM CHARTREUSE CADMIUM LEMON CADMIUM YELLOW LIGHT CADMIUM YELLOW MEDIUM CADMIUM YELLOW DEEP HANSA YELLOW LIGHT HANSA YELLOW MEDIUM HANSA YELLOW DEEP INDIAN YELLOW CADMIUM ORANGE CADMIUM ORANGE DEEP CADMIUM RED LIGHT CADMIUM RED MEDIUM CADMIUM RED DEEP PERMANENT ORANGE TrANSPARENT OrANGE NAPTHOL RED NAPTHOL SCARLET PERYLENE RED white · grey · black ALIZARIN CrIMSON MANGANESE VIOLET COBALT VIOLET ULTRAMARINE VIOLET ALIZARIN PERMANENT QUINACRIDONE RED QUINACRIDONE MAGENTA QUINACRIDONE VIOLET DIOXAZINE PURPLE TITANIUM WHITE RADIANT WHITE TITANIUM ZINC WHITE QUICK DRY WHITE FLAKE WHITE REPLACEMENT ULTRAMARINE BLUE COBALT BLUE PrUSSIAN BLUE CERULEAN BLUE COBALT TEAL INDANTHRONE BLUE PHTHALO BLUE CERULEAN BLUE HUE MANGANESE BLUE HUE PHTHALO TURQUOISE FASTMATTE TITANIUM WHITE ZINC WHITE -

"Three Unpublished Pen Boxes Preserved in the Museum of the Faculty of Applied Arts –Helwan University – Egypt- Analytical Artistic Study"

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 12, Ver. 8 (December. 2017) PP 63-75 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org "Three Unpublished Pen Boxes Preserved in the Museum of the Faculty of Applied Arts –Helwan University – Egypt- Analytical Artistic Study" Dr. Ghadeer Dardier Afify Khalifa Associate Professor - Islamic Department- Faculty of Archaeology-Fayoum University, Al- Fayoum, Egypt. Corresponding Author: Dr. Ghadeer Dardier Afify Khalifa Abstract: The Pen is a mean of science, learning, and transferring science, where Allah Ta'ala explained of what is concerning of the Pen or "by the pen" in the fourth verse of Sūrat al-ʻAlaq. This is like Allah's saying; "Who has taught by the pen". Ibn al-Qayyim-may Allah have mercy- said; "with pen, science is immortal and without writing, the news of some of the times is interrupted". From here, the importance of the pen and the pen boxes were specified, as well as the attention for the quality of the raw material from which pen were manufactured, likewise the variety of ornament and materials used in decoration. So, the analytical and artistic study of the three unpublished pen boxes preserved in the Museum of the faculty of Applied Arts -Helwan University will reflect and clarify the value and importance of the scientific life in Islamic Egypt. Keywords: Pen Boxes, Raw Material, Ornament, Metalworks, Woodwork, Floral motifs, Inscriptions. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 05-12-2017 Date of acceptance: 29-12-2017 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION The pen is a mean of science, learning, and transferring science, where Allah Ta'ala described and explained of what is concerning of the Pen or by the pen in Sūrat al-ʻAlaq.