Fairness Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industrial A

INDUSTRIAL A SPRING 2(Jo2 THE BULLETIN OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY f 1.25 FREE TO MEMBERS OF AIA What is industrial archaeology? When compiling an industrial archaeology engineering, science or technology is highly gazetteer just what constitutes an entry? What relevant. lt is difficult to understand many industrial soft of things do you put in7 How do you draw processes or for instance how a prime mover works INDUSTRIAL the boundaries? ln practice this can be quite a without a knowledge of the relevant chemistry and problem. What do you put in a gazetteer and physics etc. ARCHAEOLOGY what do you leave out? lt is hoped that these Nonetheless industrial archaeology is highly personal views will generate discussion. interdisciplinary and people from a variety of NEWS LzO backgrounds can and do make a viable contribution Robert Carr to the subject. Local historians, architects, schoolteachert librarians, engineers and artists, are Honorary President First we must distinguish between archaeology and often to be found among the active members of Prof Angus Euchanan history; both are concerned with the past. industrial archaeology societies. In studying the built 13 Hensley Road, Bath BA2 2DR Archaeology is the study of surviving remains environment many skills and viewpoints are Chairman - required. Mike Bone considering artefacts and ecofacts, lt does not Sunnyside, Avon Close, Keynsham, Bristol 851 8 1 LQ necessarily involve'digging things up'. History is the Jhe term industrial archaeology was officially Vice-Chairman study of written documents; minute bookt diaries, invented in Birmingham around the mid-l950s. Prof Marilyn Palmer letters and so on. -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume Two PART TWO THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN <2 6 ?- ti.«» *• 3 ^ 268 CHAPTER 14 EXPANSION FROM 1736 IGOSLING) TO 1771 (FAIRBANKS THE TOWN IN 1736 Sheffield in Gosling's 1736 plan was small and relatively compact. Apart from a few dozen houses across the River Dun at Bridgehouses and in the Wicker, and a similar number at Parkhill, the whole of the built-up area was within a 600 yard radius centred on the Old Church.1 Within that brief radius the most northerly development was that at Bower Lane (Gibraltar), and only a limited incursion had been made hitherto into Colson Crofts (the fields between West Bar and the river). On the western and north-western edges there had been development along Hollis Croft and White Croft, and to a lesser degree along Pea Croft and Lambert Knoll (Scotland). To the south-west the building on the western side of Coalpit Lane was over the boundary in Ecclesall, but still a recognisable part of the town.2 To the south the gardens and any buildings were largely confined by the Park wall which kept Alsop Fields free of dwellings except for the ingress along the northern part of Pond Lane. The Rivers Dun and Sheaf formed a natural barrier on the east and north-east, and the low-lying Ponds area to the south-east was not ideal for house construction. -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume One THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SHEFFIELD AND THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN cl740-c 1820 Neville Flavell February 1996 SUMMARY In the early eighteenth century Sheffield was a modest industrial town with an established reputation for cutlery and hardware. It was, however, far inland, off the main highway network and twenty miles from the nearest navigation. One might say that with those disadvantages its future looked distinctly unpromising. A century later, Sheffield was a maker of plated goods and silverware of international repute, was en route to world supremacy in steel, and had already become the world's greatest producer of cutlery and edge tools. How did it happen? Internal economies of scale vastly outweighed deficiencies. Skills, innovations and discoveries, entrepreneurs, investment, key local resources (water power, coal, wood and iron), and a rapidly growing labour force swelled largely by immigrants from the region were paramount. Each of these, together with external credit, improved transport and ever-widening markets, played a significant part in the town's metamorphosis. Economic and population growth were accompanied by a series of urban developments which first pushed outward the existing boundaries. Considerable infill of gardens and orchards followed, with further peripheral expansion overspilling into adjacent townships. New industrial, commercial and civic building, most of it within the central area, reinforced this second phase. A period of retrenchment coincided with the French and Napoleonic wars, before a renewed surge of construction restored the impetus. -

Accommodation in Sheffield

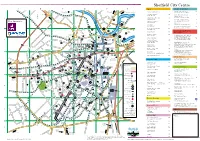

Sheffield City Centre ABCDEFArts Sport & Leisure L L T A6135 to Northern I E The Edge Climbing Centre C6 H E Kelham Island T R To Don Valley Stadium, Arena, Meadowhall Galleries and Museums General Hospital L S and M1 motorway (junction 34) John Street, 0114 275 8899 G R Museum S A E E T L E FIELD I I SHALESMOOR N ITAL V L SP P S A A N S Graves Art Gallery D4 S E Ponds Forge International E3 H L M A S N A T R S 0114 278 2600 A E E T U L T Sports Centre E R S A M S T N E E Sheaf Street, 0114 223 3400 O ST E STREET T R O R L S Kelham Island Museum C1 R Y E 1 GRN M Y 0114 272 2106 A61 T A M S H Sheffield Ice Sports Centre E6 M E P To Barnsley, Huddersfield, S T S E O G T P E R JOHNSON T A E Leeds and Manchester O R N Queens Road, 0114 272 3037 D E R R E R I R BOWLING I F Millennium Galleries D4 Map Sponsors via Woodhead F N T E E O T I E F E S T W S L G T R E E D 0114 278 2600 L S S B E SPA 1877 A4 T G I B N Y T R E R A CUT O L R O K E T I L E Victoria Street, 0114 221 1877 H A E I R 3 D S R R E C ’ G Site Gallery E5 T S T A T S T T G I E R A D E 0114 281 2077 E R W R E P R A Sheffield United Football Club C6 E O H T S O P i P T R Bramall Lane, 0870 787 1960 v E R R S N D Turner Museum of Glass B3 T H e 48 S O E A R ST P r O E I 0114 222 5500 C O E T E T D R T LOVE A P T L Transport & Travel o S A V Winter Garden D4 n A I I N Enquiries B R L R P O O N U K T Fire/Police S P F Yorkshire Artspace D5 B R I D T C Law Courts G E RE I Personal enquiries can be made at: Museum S T E 12 V i n S C O R E E T T s 0114 276 1769 T L A N a Sheffield Interchange for bus, tram T D S C A S T L B E T R West Bar E G A T E 2 l E E E W S a or coach (National Express). -

Document-0.Pdf

THE DEVELOPMENT HISTORY he Beauchief is an exclusive new BRANTINGHAM HOMES he Beauchief Hotel is one of Under Michel’s management the hotel development of luxury apartments Brantingham Homes have more than 25 Sheffield’s most iconic buildings, was extended with an additional 40 Tand detached houses – A Statement years experience in the industry with a Tsteeped in history and holding fond rooms – a significant expansion – which in Luxury Living. rich history in property conversions and memories for many of the city’s residents. led to the hotel becoming a popular venue well-designed apartment schemes. The for weddings, christenings and family Once the location of a beautiful hotel, Brantingham team are responsible for the Originally built in 1900 as the Abbeydale celebrations. Brantingham Homes are transforming this stunning restoration of Westbourne Manor Station Hotel, the building served travellers extensive site – almost two acres – into at Broomhill as well as the Old Church on passing through the local railway station. From April 2012 the venue was operated by a secure, gated community that features School Lane in Crookes. The station sat on the Sheffield to London BrewKitchen who ran the venue until New stunning landscaped open spaces alongside line, serving Beauchief and Woodseats and Year’s Eve 2015 when it closed its doors for the imposing original Beauchief building This local knowledge combined with an provided excellent links to the surrounding the final time. and contemporary newly built homes. experienced building team has always areas, including Chesterfield. It went ensured that their developments are of the through numerous name changes and The historic building will be sympathetically highest quality, whilst exceeding market became the Beauchief Station in 1914 converted into six grand apartments, requirements. -

Sheffield City Story

Sheffield City Story CASEreport 103: May 2016 Laura Lane, Ben Grubb and Anne Power Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of figures ............................................................................................................................................. 3 List of boxes ............................................................................................................................................... 4 About LSE Housing and Communities ....................................................................................................... 5 Foreword and acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 5 Sheffield About .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Geography and History .................................................................................................................. 8 Shock Industrial Collapse ......................................................................................................................... 12 Sheffield shifts towards partnerships ...................................................................................................... 16 Recovery to 2007 .................................................................................................................................... -

Local Authority Action Against Apartheid

Local Authority Action Against Apartheid http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.aam00022 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Local Authority Action Against Apartheid Author/Creator National Steering Committee on Local Authority Action Against Apartheid; United Nations Centre Against Apartheid Publisher Sheffield Metropolitan District Council Date 1985-03-00 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United Kingdom Coverage (temporal) 1960 - 1985 Source AAM Archive Rights By kind permission -

Sheffield Breastfeeding Friendly Award Type of Venue by Area Name of Venue Address

Sheffield Breastfeeding Friendly Award Type of Venue by Area Name of Venue Address Sheffield 1 Town Hall Sheffield Town Hall Pinstone Street S1 2HH Births, Deaths & Marriages Registrars Sheffield Register Office Town Hall, Pinstone street, Sheffield S1 2HH Library Central Library Surrey Street, Sheffield S1 1XZ Cinema, Bar & Café Showroom Cinema 15 Paternoster Row, Sheffield S1 2BX Café PJ Taste @ Site Canteen 1A Brown Street, Sheffield S1 2BS Church/Cathedral Sheffield Cathedral Church Street, Sheffield S1 1HA Sport & Leisure Venues Sheffield International Venues Don Valley Stadium, Worksop Road, Sheffield S9 3TL Concert Venue Sheffield City Hall Barkers Pool, Sheffield S1 2HB Leisure Centre Ponds Forge Sheaf Street, Sheffield S1 2BP Council Building First Point - Howden House First Point, Howden House, Sheffield S1 2SH Bus Station SYPTE Sheffield Interchange, Pond Hill, Sheffield S1 2BG Café Starbucks Unit 6, Orchard Square, Sheffield S1 2FB Retail Store Boots the Chemists 4-6 High Street, Sheffield S1 1QF Retail Store Mothercare World 200-202 Eyre Street, Sheffield S1 4QZ Retail Store Mothercare 19-21 Barkers Pool, Sheffield S1 2HB Retail Store John Lewis Barkers Pool, Sheffield S1 2HB Retail Store Wilko 34-36 Haymarket, Sheffield s1 2AX Museum & Gallery Millennium Gallery Arundel Gate, Sheffield S1 2PP Café Crucible Corner Tudor Square, Sheffield S1 2JE Clinic Sheffield Contraception & Sexual Health Clinic 1 Mulberry Street, Sheffield S12PJ Café Blue Moon Café St James Street, Sheffield S1 2EW Offices Sheffield Homes (6 Offices) New Bank House, Queen Street, Sheffield S1 2XX Retail Store Debenhams The Moor, Sheffield S1 3LR Café Fusion Café Arundel Street, Sheffield S1 2NS Café & Therapy Centre Woodland Holistics 7 Campo Lane, Sheffield S1 Church and Hall Victoria Hall Methodist Church Norfolk Street, Sheffield S1 2JB Council Building Redvers House Union Street, Sheffield S1 2JQ Sheffield Hallam University - Public Venues Adsetts Learning Centre (inc. -

Geography 497: International Field Study, Summer 2003 Field Trip

Geography 497: International Field Study, Summer 2003 Field Trip Summary SUNDAY June 22: 7.00 p.m. Dinner, Halifax Hall, Sheffield University. Final pre-trip preparations are discussed in a local pub, conveniently located within 10 minutes walk. MONDAY, June 23: 7.30 a.m. Breakfast. 9.15 a.m. We begin by walking towards Endcliffe Park and Whiteley Woods where Shepherd Wheel is located. On the way, we pass some Victorian housing and at the junction of Ecclesall Road, Hunter’s Bar, now covered by trees, is the site of a former toll gate (really toll house). Hunter’s Bar was erected around 1700 as part of a turnpike trust to charge road users for the upkeep of the road. There were 10 turnpike trusts controlling 16 toll gates in Sheffield. Hunter’s Bar was the last to close in 1884. Photo 1: Geography 497 in Endcliffe Park. Parks for recreational purposes are a long established, widespread feature of the Sheffield landscape found throughout the city (outside of the central area). Part of the Sheffield web-based promotional literature claims the city is one of the greenest in Europe, including 78 public parks, 10 gardens and 170 woodlands. Many of the parks are large. Photo 2: Shepherd Wheel 9.52 a.m. Shepherd Wheel is on the Porter River, Whiteley Woods. The site comprises cutlery grinding and polishing operations and a water wheel. The latter which provided power for grinding stones (made out of local sandstone) was driven by a dam created by diverting water from the Porter River. -

DP2030 City Pads 1

Sheffield City Centre ABCDEF L L T I E A6135 to Northern H E Kelham Island T R To Don Valley Stadium, Arena, Meadowhall Arts Sport & Leisure General Hospital L S and M1 motorway (junction 34) G R Museum S A E E LD T L E FIE I I SHALESMOOR N ITAL V L SP P S A The Edge Climbing Centre C6 A N S Galleries and Museums S E H L M A S N John Street, 0114 275 8899 A T R S A E E T U L T E R S A T M S E T Graves Art Gallery D4 T N RE E E O S E ST T R Ponds Forge International E3 O R L S 0114 278 2600 R N R Y E 1 G M Sports Centre A61 N Y A G T O M S S H M E N P To Barnsley, Huddersfield, IN S T H S Sheaf Street, 0114 223 3400 E O L G T P E R JO T Kelham Island Museum C1 A E Leeds and Manchester O W R N D E R O R E R I R B I F Map Sponsors via Woodhead F N T E E 0114 272 2106 O T I E F E S T W S L G T R E Sheffield Ice Sports Centre E6 E D L S S B E T G I B N Y R T R CUT Queens Road, 0114 272 3037 E A K Millennium Galleries D4 O L R O E T I L E H A E I R 4 D S R R E C ’ G T S T A T 0114 278 2600 S T T G I E R A SPA 1877 A4 D E E R W R E P R A E O Victoria Street, 0114 221 1877 H T S O Site Gallery E5 P P T R v E R R S N D 0114 281 2077 T H e 55 S O T E O A R S P r I Sheffield United Football Club C6 C E O E E T E V T R D A Bramall Lane, 0114 221 1889 T LO P T L Turner Museum of Glass B3 o S A V n A I 0114 222 5500 I N B R L R P O O Transport & Travel N U K T Fire/Police S P F Winter Garden D4 B R I D T C Law Courts G E RE I Museum S T E 13 V i n S C O R E E T T s Enquiries T L A N a T D S C A S T L B E T R West Bar E G A T E 3 l Yorkshire Artspace D5 E E E W S a T Police Station E S T B A R N n Personal enquiries can be made at: R N a 0114 276 1769 T E I W S T E G Magistrates Victoria C Sheffield Interchange for bus, tram E R A 23 G P H N E I Sheffield The Court T Quays 2 E R R I N or coach (National Express). -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Overview and Scrutiny

Public Document Pack Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee Friday 14 February 2020 at 10.00 am To be held at the Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Sheffield, S1 2HH The Press and Public are Welcome to Attend Membership Councillors Mick Rooney (Chair), Ian Auckland, Steve Ayris, Ben Curran, Denise Fox, Julie Grocutt, Tim Huggan, Douglas Johnson, Mike Levery, Cate McDonald, Sioned-Mair Richards and Jim Steinke Substitute Members In accordance with the Constitution, Substitute Members may be provided for the above Committee Members as and when required. PUBLIC ACCESS TO THE MEETING The Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee comprises the Chairs and Deputy Chairs of the four Scrutiny Committees. Councillor Cate McDonald Chairs this Committee. Remit of the Committee Effective use of internal and external resources Performance against Corporate Plan Priorities Risk management Budget monitoring Strategic management and development of the scrutiny programme and process Identifying and co-ordinating cross scrutiny issues A copy of the agenda and reports is available on the Council’s website at www.sheffield.gov.uk. You can also see the reports to be discussed at the meeting if you call at the First Point Reception, Town Hall, Pinstone Street entrance. The Reception is open between 9.00 am and 5.00 pm, Monday to Thursday and between 9.00 am and 4.45 pm. on Friday. You may not be allowed to see some reports because they contain confidential information. These items are usually marked * on the agenda. Members of the public have the right to ask questions or submit petitions to Scrutiny Committee meetings and recording is allowed under the direction of the Chair. -

The Campus in Context Opportunities + Constraints

PART 2 THE CAMPUS IN CONTEXT OPPORTUNITIES + CONSTRAINTS 15 DRAFT for consultation Autumn 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD MASTERPLAN 2.1 Location The University of Sheffield central campus is located on A61 the west slopes of the city centre. The campus forms a city gateway characterised by a change from leafy suburbia to a more built up urban environment. The central campus is often identified as sitting within the St George’s Quarter of the city, A61 though reaches beyond this quarter in all directions, and as such has highly permeable boundaries. The central campus is divided by Upper Hanover Street, a north-south section of the A61 city ring road, and further divided by significant east-west roads A57 to M1 Western Bank and Broad Lane. The resulting campus zones are known as the east, north and west campus. The academic and social shape of these is described in later sections. On foot, the centre of the campus is approximately 15 minutes from the city centre, and 25 minutes from Midland Rail Station, the Bus Station and Sheffield Hallam University, which A57 A61 are east of the city centre. A61 North Campus A625 A621 Google copyright for aerial image component Principal routes to the city A57 East Campus West Campus 16 LOCATION KEY 1 Weston Park 2 Royal Hallamshire Hospital 3 Firth Hall 12 4 UoS Students’ Union 5 St George’s Church 6 Devonshire Green 7 City Hall 8 Sheffield Town Hall 9 Sheffield Hallam University 10 Bus Station 11 Midland Station 12 A61 Ring Road 1 University buildings shaded blue 5 3 Whilst the Hallamshire Hospital and 7 Sheffield Children’s Hospital are not 4 10 owned by the University of Sheffield, 8 we do have significant numbers of staff based in these two locations under 9 long-term arrangements which is why 6 they are included here.