Volume 9, Number 2, Fall 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL UPDATE Winter 2019

ANNUAL UPDATE winter 2019 970.925.3721 | aspenhistory.org @historyaspen OUR COLLECTIVE ROOTS ZUPANCIS HOMESTEAD AT HOLDEN/MAROLT MINING & RANCHING MUSEUM At the 2018 annual Holden/Marolt Hoedown, Archive Building, which garnered two prestigious honors in 2018 for Aspen’s city council proclaimed June 12th “Carl its renovation: the City of Aspen’s Historic Preservation Commission’s Bergman Day” in honor of a lifetime AHS annual Elizabeth Paepcke Award, recognizing projects that made an trustee who was instrumental in creating the outstanding contribution to historic preservation in Aspen; and the Holden/Marolt Mining & Ranching Museum. regional Caroline Bancroft History Project Award given annually by More than 300 community members gathered to History Colorado to honor significant contributions to the advancement remember Carl and enjoy a picnic and good-old- of Colorado history. Thanks to a marked increase in archive donations fashioned fun in his beloved place. over the past few years, the Collection surpassed 63,000 items in 2018, with an ever-growing online collection at archiveaspen.org. On that day, at the site of Pitkin County’s largest industrial enterprise in history, it was easy to see why AHS stewards your stories to foster a sense of community and this community supports Aspen Historical Society’s encourage a vested and informed interest in the future of this special work. Like Carl, the community understands that place. It is our privilege to do this work and we thank you for your Significant progress has been made on the renovation and restoration of three historic structures moved places tell the story of the people, the industries, and support. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies Collection Mss.00020

Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies collection Mss.00020 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit February 10, 2015 History Colorado. Stephen H. Hart Research Center 1200 Broadway Denver, Colorado, 80203 303-866-2305 [email protected] Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies collection Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical note................................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Accession numbers........................................................................................................................................ 9 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 -

UIC University Library Newsletter Fall 2018

A publication of the UIC University Library | FALL 2018 Centered on student success Library’s programs and activities crucial to helping students feel they belong on campus The University of Illinois at Chicago takes a multipronged approach to ensuring that all of its students have an equal opportunity to receive a high-quality education that prepares them to graduate and achieve their future life goals. A wide range of student success initiatives support students (especially undergraduates) in every phase of their educational progress at UIC. These include preparing students to manage their time and course loads, giving them paid internship opportunities in their fields and offering them experiences that encourage leadership development, to mention only a few. Learn more at studentsuccess.uic.edu. Participation from each of the colleges at UIC is essential to these efforts. The UIC University Library plays a unique and central role in student success because it is the only college that collaborates with and serves all of the other UIC colleges. Additionally, the Library’s physical spaces are used by more than 3.2 million visitors each year for a variety of purposes, from collaboration to quiet study, to research, classes and workshops, to events held by UIC’s academic and cultural centers and much more. The Library continually strives to cultivate partnerships and to create a welcoming and productive environment for all. NEWSLETTER The Library is currently focused on working toward three goals that support student success: 1. Instill confidence in students by giving them the knowledge, tools and resources to effectively find and evaluate information in order to complete their class assignments 2. -

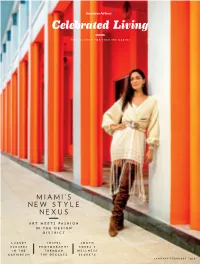

Miami's New Style Nexus

EXCLUSIVELY FOR PREMIUM CABINS MIAMI’S NEW STYLE NEXUS ART MEETS FASHION IN THE DESIGN DISTRICT LUXURY TRAVEL SOUTH ESCAPES PHOTOGRAPHY KOREA ’ S IN THE THROUGH WELLNESS CARIBBEAN THE DECADES SECRETS JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 001_COVER.rev2.indd 1 12/12/2018 16:51 Herbert Bayer’s Marble Garden, 1955, at The Aspen Institute. Below: A Bayer poster from 1951 CULTURE In 1946, Walter Paepcke, chairman of the – Container Corporation of America, brought Bayer to the former mining town to create a “Bauhaus for the corporate mind.” He designed Bauhaus The Aspen Institute, and the low-slung Aspen Meadows Resort on the campus—complete with Bertoia chairs and balcony dividers party painted red and yellow—is still like stepping To celebrate the centennial of the German into a Bauhaus wonderland. art movement, cities around the This year, The Aspen Institute is looking world—including Aspen—are mounting a back to its roots: The Bauhaus will be a subject host of exhibitions and festivals of the Aspen Ideas Festival in June, followed by a symposium in August. A Bayer exhibition ASPEN AND has been drawn from his campaign for the he original 1919 Bauhaus—a German THE BAUHAUS Container Corporation, merging artwork by art movement incorporating designers, – such luminaries as René Magritte with T artists and architects—became famous In January, the annual observations from writers like Samuel Wintersköl festival will for breaking down the distinctions between Johnson. And Bayer’s 1955 Marble Garden, an entail a Bauhaus-inspired fine and commercial art. The Bauhaus “form Wintersculpt of snow, outdoor array of marble slabs surrounding a follows function” philosophy influenced, coordinated by the influential fountain, is still a campus landmark. -

Object - Photo Report

Object - Photo Report 82.57.5 Name Moving image Photographer Kingery, Hugh Title Skiing in Colorado Non-original Title Skiing in Colorado Description Black-and-white 16mm movie on cellulose acetate film stock made circa 1950-1955, shot by Hugh Kingery. The film has not been reviewed (as of 7/16/2015) but appears to depict skiing in Colorado. The film is approximately 200 ft. in length. This film is #1 in a series of 3. Inscription The film reel in in a cardboard box with a Colorado Historical Society label. It reads: "Skiing in Colorado / 16mm film by Mr. Kingery / Gift of Mrs. Elinor Kingery / 4629 East Cedar Denver, Colorado 80222 / June 1982" ; Handwritten on label: "1982 prints" Subject Skis and skiing--Colorado, Amateur films Provenance Gift of Elinor Kingery, 1982. Collection Name Hugh M. and Elinor Kingery collection (Ph.00244) 82.57.6 Name Moving image Photographer Kingery, Hugh Title Skiing in Colorado Non-original Title Skiing in Colorado Description Black-and-white 16mm home movie on cellulose acetate film stock made circa 1950-1955, shot by Hugh Kingery. The film has not been reviewed (as of 7/16/2015) but appears to depict skiing in Colorado. The film is approximately 100 ft. in length. This film is #2 in a series of 3. Inscription The film reel in in a cardboard box with a Colorado Historical Society label. It reads: "Skiing in Colorado / 16mm film by Mr. Kingery / Gift of Mrs. Elinor Kingery / 4629 East Cedar Denver, Colorado 80222 / June 1982" ; Handwritten on label: "1982 prints" Subject Skis and skiing--Colorado Provenance Gift of Elinor Kingery, 1982. -

Guide to the Elizabeth H. Paepcke Papers 1889-1994

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Elizabeth H. Paepcke Papers 1889-1994 © 2004 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 4 Descriptive Summary 4 Information on Use 4 Access 4 Citation 4 Biographical Note 4 Scope Note 6 Related Resources 8 Subject Headings 9 INVENTORY 9 Series I: Personal 9 Subseries 1: Engagements 10 Subseries 2: Calendars and Guest Books 14 Subseries 3: Financial and Legal 14 Subseries 4: Walter Paepcke 17 Subseries 5: Albert Schweitzer 21 Subseries 6: General 23 Series II: Correspondence 25 Series III: Activities and Interests 104 Series IV: Travel 158 Series V: Nitze Family 167 Series VI: Adlai Stevenson 172 Series VII: Mortimer Adler 174 Series VIII: Photographs 176 Subseries 1: Family 176 Subseries 2: Social Events and Leisure Activities 178 Subseries 3: Travel 179 Subseries 4: Aspen 180 Subseries 5: Aspen Institute, Goethe Festival, and Celebrities 181 Subseries 6: Miscellaneous 183 Series IX: Audio-Visual 185 Series X: Awards, Plaques and Ephemera 186 Subseries 1: Awards and Plaques 186 Subseries 2: Ephemera 187 Series XI: Writings, Newspaper and Magazine Clippings 189 Subseries 1: Writings of Others 189 Subseries 2: Newspaper and Magazine Clippings 192 Series XII: Family Correspondence and Oversize 196 Series XIII: Addenda 197 Subseries 1: Personal 198 Subseries 2: Correspondence 202 Subseries 3: Travel 207 Subseries 4: Awards, Plaques, and Ephemera 208 Subseries 5: Writings, Newspaper, and Magazine clippings 208 Subseries 6: Oversize 209 Subseries 7: Restricted 209 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.EHPAEPCKE Title Paepcke, Elizabeth H. Papers Date 1889-1994 Size 151 linear feet (255 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. -

ED264785.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 264 785 HE 018 962 AUTHOR Eurich, Nell P. TITLE Corporate Classrooms: The Learning Business. A Carnegie Foundation Special Report. INSTITUTION Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, New York, N.Y. REPORT NO ISBN-0-931050-25-1 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 172p. AVAILABLE FROMPrinceton University Press, 3175 Princeton Pike, Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 ($8.50 plus $2.00 postage and handlins). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Historical Materials (060)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Basic Skills; *Business; Continuing Education; *Degrees (Academic); Educational History; Educational Research; *Education Work Relationship; Industrial Training; *Indus* y; Inplant Programs; Institutional Characteristics; Job Training; Management Development; *Postsecondary Education; *Professional Training; Staff Development; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Corporate Education ABSTRACT Education in U,S. industry and business is discussed, and the history of business-based education is tracedto nineteenth century efforts to meet both the demands of productivity andthe training of workers. After discussing the sizeand scope of efforts to train employees, reasons for corporate trainingare identified. Four dimensions of the corporate learning enterpriseare considered: in-house educational programs, educational andtraining facilities, degree-granting institutions, and the satellite university.Specific topics include: facilities for corporate education;educational structure; the position of -

View Brochure

ASPEN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Sites and Information WHEELER/STALLARD MUSEUM WHEELER/STALLARD MUSEUM & ARCHIVES The Wheeler/Stallard Museum is a Queen promptly sold it Anne-style, Victorian mansion built around to the Stallards 1888 by Jerome B. Wheeler, located in Aspen’s at the same charming West End, and home to the Aspen price. As Aspen Historical Society. While the main floor is the fortunes waned, re-creation of a late 1800s parlor – where people Ella remained in are encouraged to gather and sit – the second the house, closing floor hosts rotating exhibits. In the summer, the off fireplaces Wheeler/Stallard House in 1890-92 surrounding park and gardens are used for public and most of the rooms except the kitchen, programs and special events. dining room and parlor (used as her bedroom) to conserve heat and save money. In 1945, she sold the home to W.C. Tagert who immediately sold it Behind the Wheeler/ Stallard Museum sits the to Walter Paepcke, widely considered the driver Archive Building, home of Aspen’s emergence as a resort. to more than 45,000 The house served as overflow guest quarters objects, photographs and for the Hotel Jerome, then employee housing documents. The building is open to the public for for the hotel. By the early 1960s, Elizabeth research (appointments Paepcke remodeled the house and Alvin Eurich, recommended) and guests the president of the Aspen Institute, and his are encouraged to dig family moved in. The Aspen Historical Society through Aspen’s history. first rented the Wheeler/Stallard house in 1968, eventually purchasing the property in 1969. -

Herbert Bayer and the Dilemma of Architectural Historiography

102 LEGACY + ASPIRATIONS Point and Line into Landscape: Herbert Bayer and the Dilemma of Architectural Historiography DAVID RIFKIND Columbia University Any reconsideration of the institutionalization and subsequent eclipse 1960's and '70s is the child of Minimalism, Constructivism and of Modernism in American architecture must include a consider- Constantin Brancusi. This paper, while not countering that filiation, ation of historiography in twentieth-century American architecture. offers another - parallel - history of earthworks, one that finds a The widespread removal of political and poetic content from Euro- powerful catalyst in the experiments of Surrealism and traces a wide pean precedents by American architects and critics has to be recog- migrationof sculptural concerns to the landscape, beginning as early nized as integral to a framework of aestheticization and as the 1930's. The importance of this historical construct to architec- instrumentalization necessary to an ethos of production - an ethical ture is that the translation (the word is offered here in its broadest horizon within which all conceptual contradictions are reconciled sense) between sculpture and landscape would have been impossible among a diverse cast of monuments. History, for American archi- without architecture as a middle term. tects, has been a selective process of sanitizing precedents for a The key role in this drama is played by Herbert Bayer. Bayer - discretely bound profession free of the nuance and difficulty that the former Bauhaus master widely known for his innovations in accompany poetic and political practices. typography andexhibitiondesign-built Grass Moundat the Aspen Key to the instrumentalization of architectural history has been Institute for the Humanities in 1955. -

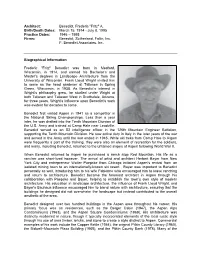

Fritz Benedict

Architect: Benedict, Frederic "Fritz" A. Birth/Death Dates: March 15, 1914 - July 8, 1995 Practice Dates: 1946 – 1995 Firms: Benedict, Sutherland, Fallin, Inc. F. Benedict Associates, Inc. Biographical Information Frederic "Fritz" Benedict was born in Medford, Wisconsin, in 1914, and earned his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Landscape Architecture from the University of Wisconsin. Frank Lloyd Wright invited him to serve as the head gardener at Taliesen in Spring Green, Wisconsin, in 1938. As Benedict’s interest in Wright’s philosophy grew, he studied under Wright at both Taliesen and Taliesen West in Scottsdale, Arizona, for three years. Wright’s influence upon Benedict’s work was evident for decades to come. Benedict first visited Aspen in 1941 as a competitor in the National Skiing Championships. Less than a year later, he was drafted into the Tenth Mountain Division of the U.S. Army and trained at Camp Hale near Leadville. Benedict served as an S2 intelligence officer in the 126th Mountain Engineer Battalion, supporting the Tenth Mountain Division. He saw active duty in Italy in the later years of the war and served in the Army until the war ended in 1945. While ski treks from Camp Hale to Aspen were frequently a part of the training, they were also an element of recreation for the soldiers, and many, including Benedict, returned to the untamed slopes of Aspen following World War II. When Benedict returned to Aspen he purchased a ranch atop Red Mountain. His life as a rancher was short-lived however. The arrival of artist and architect Herbert Bayer from New York City and entrepreneur Walter Paepcke from Chicago initiated Aspen’s revival from an isolated mining town to an internationally-known ski resort. -

The Legacy of Herbert Bayer

the legacy of herbert bayer recent gifts and loans to the Aspen Institute This publication has been produced in conjunction with the exhibition The Legacy of Herbert Bayer: Recent Gifts and Loans to the Aspen Institute, curated by David Floria and presented in the Resnick Gallery, Doerr-Hosier Center, The Aspen Institute, Aspen, Colorado. Opening December 29, 2013 Cover photo: Leinie Schilling Bard, Herbert Bayer, 1983 (#1) Opposite photo: Ferenc Berko, The Aspen Institute and Music Tent, 1965 Photo courtesy of BERKO Photo (#2) Inside back cover: Herbert Bayer, deposition, 1940 (#33) Back cover: Herbert Bayer, landscape, 1982 (#34) Printed in an edition of 1,000 the legacy of herbert bayer recent gifts and loans to the Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute and Music Tent, 1965 (#2) essay by david floria and lissa ballinger biographical background by bernard jazzar belle nuit geometrique, 1978/76 (#3) 2 foreword The Legacy of Herbert Bayer: Recent Gifts and Loans to the This exhibition clearly illustrates his commitment to Aspen Institute signals a new focus in the visual art pro- Bauhaus ideals by presenting a diverse selection from his gramming of the Aspen Institute. The exhibition formal- oeuvre. While this exhibition is a permanent installation, izes the commitment to the collection, study, appreciation, it will evolve as temporary loans are replaced by gifts and and preservation of the work of this master artist, acknowl- new loans. edging his seminal contribution to the Institute. It is the third in a series of exhibitions concerning Herbert Bayer in the Resnick Gallery of the Doerr- Hosier Center.