The Wheeler-Stallard House: an Interpretative History, 1888-1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL UPDATE Winter 2019

ANNUAL UPDATE winter 2019 970.925.3721 | aspenhistory.org @historyaspen OUR COLLECTIVE ROOTS ZUPANCIS HOMESTEAD AT HOLDEN/MAROLT MINING & RANCHING MUSEUM At the 2018 annual Holden/Marolt Hoedown, Archive Building, which garnered two prestigious honors in 2018 for Aspen’s city council proclaimed June 12th “Carl its renovation: the City of Aspen’s Historic Preservation Commission’s Bergman Day” in honor of a lifetime AHS annual Elizabeth Paepcke Award, recognizing projects that made an trustee who was instrumental in creating the outstanding contribution to historic preservation in Aspen; and the Holden/Marolt Mining & Ranching Museum. regional Caroline Bancroft History Project Award given annually by More than 300 community members gathered to History Colorado to honor significant contributions to the advancement remember Carl and enjoy a picnic and good-old- of Colorado history. Thanks to a marked increase in archive donations fashioned fun in his beloved place. over the past few years, the Collection surpassed 63,000 items in 2018, with an ever-growing online collection at archiveaspen.org. On that day, at the site of Pitkin County’s largest industrial enterprise in history, it was easy to see why AHS stewards your stories to foster a sense of community and this community supports Aspen Historical Society’s encourage a vested and informed interest in the future of this special work. Like Carl, the community understands that place. It is our privilege to do this work and we thank you for your Significant progress has been made on the renovation and restoration of three historic structures moved places tell the story of the people, the industries, and support. -

Agenda City Council Work Session

AGENDA CITY COUNCIL WORK SESSION July 15, 2019 4:00 PM, City Council Chambers 130 S Galena Street, Aspen I. COUNCIL ROUNDTABLE 4:00-4:10 II. WORK SESSION II.A. Board and Commission Interviews (round 2) II.B. Retreat follow up regarding transportation and housing framework 1 1 MEMORANDUM TO: Mayor and City Council FROM: Linda Manning, City Clerk DATE OF MEMO: July 11, 2019 MEETING DATE: July 15, 2019 RE: Citizen board appointments (round 2) City Council has been conducting board interviews for various citizen boards twice a year, typically in January and July. In the past, not all boards have been interviewed by Council including the Animal Shelter, Building Code Board of Appeals and the Kid’s First Board. Mayor Torre has indicated that he would like Council to interview all perspective board members. To be consistent with how board interviews have happened in the past and due to the number of applicants for each board, staff is recommending that Council interview all members for each board at the same time instead of conducting individual interviews. Included in the packet for each board will be a list of the current members, the most recent ordinance or code section as well as bylaws if available. 2 Wheeler Board of Directors 1 regular member opening 7 regular members, 1 alternate member and 1 ex officio member Current Members Chip Fuller – chair – reapplying Tom Kurt – expires 2020 Richard Stettner – expires 2022 Christine Benedetti – vice chair – expires 2023 Nina Gabianelli – expires 2020 Amy Mountjoy – expires 2023 Ziska Childs – -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

TO: Aspen Historic Preservation Commission Frovf: Amy Guthrie, Historic Preservation Officer

{@s7 EMORAI\DUM TO: Aspen Historic Preservation Commission fROVf: Amy Guthrie, Historic Preservation Officer RE: Ute Cemetery National RegisterNomination DATE: July 11,2001 SUMMARY: Please review and be prepared to comment on the attached National Register nomination, just completed for Ute Cemetery. We received a grant to do this project. The author of the nomination is also under contract to complete a management plan for the cemetery. He, along with a small team of people experienced in historic landscapes and conservation of grave markers, will deliver their suggestions for better stewardship of the cemetery in September. The City plans to undertake any necessary restoration work in Spring 2002. USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 4 UTE CEMETERY PITKIN COUNTY. COLORADO Name of Property CountY and State 1n Aannrnnhinol l)ata Acreage of Property 4.67 acres UTM References (Place additional UTM references on a continuation sheet) 2 1 13 343s00 4338400 - Zone Easting Northing %16- A-tns Nortffis z A Jee continuation sheet Verbal Boundary Description (Describe the borndaries of the property on a continuation sheet ) Bounda ry Justification (Explain wtry the boundaries were selected on a continuation sheet.) 1 1. Form Prepared Bv NAME/titIE RON SLADEK. PRESIDENT organization TATANKA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATES. lNC. date 28 JUNE 2001 street & number P.0. BOX 1909 telephone 970 / 229-9704 city or town stateg ziP code .80522 Additional Documentation Submit the fdloaing items with $e completed form: Continuation Sheets Maps A USGS map (7.5 or l5 minute series) indicating the property's location. A Sketch mapfor historic districts and properties having large acreage or numerous resources. -

Three Perfect Days Colorado Rockies Story and Photography by Sam Polcer

20 HEMI SKI 15 NOVEMBER 2015 THREE PERFECT DAYS COLORADO ROCKIES STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY SAM POLCER INCE FOLKS BEGAN DELVING INTO THE ROCKIES FOR GOLD BACK IN THE MID-1800S, THIS EXTRAVAGANTLY BEAUTIFUL PART OF THE UNITED STATES HAS BEEN DOTTED S WITH BOOMTOWNS, EACH OF THEM A MAGNET FOR ADVENTURERS AND ROMANTICS. WHILE THE ADVENTURERS REMAIN, PICKAXES HAVE BEEN REPLACED BY SKI POLES, AND THE RICHES ARE ASSOCIATED WITH EXPERIENCES RATHER THAN MATERIAL WEALTH. TODAY, TOWNS LIKE BRECKENRIDGE, VAIL AND ASPEN BRIM WITH FIVE-STAR HOTELS, SOPHISTICATED EATERIES, WORLD-CLASS MUSEUMS AND BUZZING NIGHTCLUBS. BUT MAKE NO MISTAKE, THE BIGGEST DRAW OF ALL IS THE MOUNTAINS—AND THE UNPARALLELED THRILL OF HURTLING DOWN THEM. THE REAL TREASURE, IT TURNS OUT, WAS ON THE SURFACE ALL ALONG. 64 064_HEMI1115_3PD.indd 64 07/10/2015 11:12 Skiers hiking above the Kensho SuperChair to the top of Breckenridge’s Peak 6, 12,573 feet above sea level 064_HEMI1115_3PD.indd 65 07/10/2015 11:12 THREE PERFECT DAYS 2005 YEAR AUTHOR HUNTER S. THOMPSON’S ASHES WERE SHOT OUT OF A CANNON NEAR ASPEN A sugar cinnamon crumble doughnut from Sweet ColoraDough Four turns into the first run of the day, I wonderder DAY ONE aloud how common it is for Sky’s clients to hollerer with glee, which is what I do while following himm In which Sam goes to Breckenridge to test his lung down an untouched run on Peak 8. “Pretty typical,”al,” capacity and cry over the beer at Broken Compass he says, smiling. It’s been a while since I’ve skied, butbut one thing I remember, aside from how euphoric those firstst tuturnsrns on a perfectly groomed trail can feel, is that hardcore skiers T’S ALWAYS A GOOD IDEA to make note of what’s often appear to have life’s mysteries figured out. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

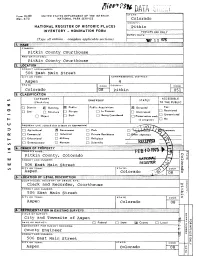

M COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF

/!?"' . P »!» n .--. - •" - I A ^UL. STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Colorado COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Pitkin INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) UN 1 2 W5 COMMON: pitkin county Courthouse AND/OR HISTORIC: pitkin County courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Aspen STATE Colorado 08 pitkin 051 BliMsfiiiiiiQi CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSH.P STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District jg Building 89 Public Public Acquisition: (X) Occupied Yes: ,, .1 CH Restricted Q Site Q Structure D Private Q In Process Unoccupied r— i D • d— Unrestricted D Object D Both [~] Being Considered |-j p reservat|on w in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [~1 Agricultural ps| Government | | Park Q Commercial CD Industrial ( | Private Residence C] Educational 1 1 Military [ | Religious Q Entertainment l~l Museum [~1 Scientific OWNER'S NAME-. ffffyws Pitkin county, Colorado Colorado STREET AND NUMBER: —NATIONAL 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Aspen Colorado m j~i 08 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Clerk and Recorder, Courthouse COUNTY: Pitkin STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE Aspen Colorado 08 TITUE OF SURVEY: City and Townsite of Aspen DATE OF SURVEY: |~] Federal n State County Q Loca -J.A DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: County Engineer STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Aspen Colorado 08 (Check One) Excellent Q Good Q Fair Deteriorated Q Roins Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Chock One) D Altered D Unaltered Q~] Moved Q Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL ("// Jcnoivn.) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Pitkin County acquired Lots K, L, M, N, and O, Block 92 of the Original Aspen Townsite in May of 1890. -

Macys Janelle Godfrey.Pdf

M a c y ’ s Introduce - Macy's, Inc., originally Federated Department Stores, Inc., is an American holding company headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio. It is the owner of department store chains Macy's and Bloomingdale's, which specialize in the sales of clothing, footwear, accessories, bedding, furniture, jewelry, beauty products, and housewares; and Bluemercury, a chain of luxury beauty products stores and spas. As of 2016, the company operated approximately 888 stores in the United States, Guam, and Puerto Rico Its namesake locations and related operations account for 90% of its revenue. - - Macy's was founded by Rowland Hussey Macy, who between 1843 and 1855 opened four retail dry goods stores, including the original Macy's store in downtown Haverhill, Massachusetts, established in 1851 to serve the mill industry employees of the area. They all failed, but he learned from his mistakes. Macy moved to New York City in 1858 and established a new store named "R. H. Macy & Co." on Sixth Avenue between 13th and 14th Streets, which was far north of where other dry goods stores were at the time On the company's first day of business on October 28, 1858 sales totaled US$11.08, equal to $306.79 today. From the beginning, Macy's logo has included a star, which comes from a tattoo that Macy got as a teenager when he worked on a Nantucket whaling ship, the Emily Morgan Introduce - As the business grew, Macy's expanded into neighboring buildings, opening more and more departments, and used publicity devices such as a store Santa Claus, themed exhibits, and illuminated window displays to draw in customers. -

Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies Collection Mss.00020

Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies collection Mss.00020 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit February 10, 2015 History Colorado. Stephen H. Hart Research Center 1200 Broadway Denver, Colorado, 80203 303-866-2305 [email protected] Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies collection Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical note................................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Accession numbers........................................................................................................................................ 9 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 -

Hotel & Travel Information

Hotel & Travel Information HOTELS The Aspen Institute has secured and negotiated preferred rates at select Aspen hotels for Aspen Children’s Forum guests. Hotels, rates and information on securing reservations follows. July is peak season in Aspen, therefore guests are strongly encouraged to book hotel rooms as soon as possible. Availability at each hotel is on a first-come, first-served basis. Negotiated rates are for the nights of Wednesday, July 12, and Thursday, July 13, 2017. Please discuss rates for pre- and post-event night lodging directly with hotels for extended stays. Hotel Jerome Website: https://hoteljerome.aubergeresorts.com/ Address: 330 E Main St., Aspen, CO 81611 Negotiated Rate: $475 per night, plus fees and taxes Make a Reservation: Please call Veronica at 970-429-7696 to make a reservation. Reference the “Aspen Children’s Forum.” ASPEN CHILDREN’S FORUM — HOTEL & TRAVEL INFORMATION Aspen Meadows Resort Website: https://www.aspenmeadows.com/ Address: 845 Meadows Rd., Aspen, CO 81611 Negotiated Rate: $285 per night, plus fees and taxes Make a Reservation: Please visit this link to make a reservation within our room block: https://aws.passkey.com/go/ChildrensForum2017 The Limelight Hotel Website: https://www.limelighthotels.com/aspen Address: 355 S Monarch St., Aspen, CO 81611 Negotiated Rate: The room block is FULL, so the negotiated rate is no longer available. However, rooms are still available at a higher rate. Please call the Limelight directly to request the current rate. Make a Reservation: Please email [email protected] or call 800-433-0832. The Gant Condominium Resort Website: http://www.gantaspen.com/ Address: 610 S W End St., Aspen, CO 81611 Negotiated Rates: One Bedroom Condo/One Bath $295 Two Bedroom Condo /Two Bath $395 One Bedroom Condo/One Bath Premier $355 Two Bedroom Condo /Two Bath Premier $395 Three Bedroom Condo /Three Bath Premier $645 Make a Reservation: Please call The Resort Reservations Department at 1-800-345-1471 and reference the “Aspen Institute Children’s Forum” to book a room. -

Tha American J L.IH ~~ UI!J I!J, Louis Inoersoii, SEC.·M.IS

ASPEN HISTOrliC/\L SOCIETY )Cfi3 ACCESSION NO. ....4..~.,.~.t..: ...1. ~,J11to n" C FflAIlK KIRCIlIJOF, PIlESln::::l i"l~qvnl"1I'11lI • I11l c. F. STAlll, VICE·PRESIOEIIT Tha American J l.IH ~~ UI!J I!J, lOUIS InOERSOII, SEC.·m.IS. MANUFACTURERS OF BANK, OFFICE, STORE AND BAR FIXTURES TEl. UAiR 59. OFFICE & FACTORI: 1232-46 ARAPAHOE ST., DENVER, COLO. ASP1<lN 138 ASPgN --~----------- Lewis H. 'l'omldlls, Prost. F. M. Yates, Seq Henry H. Tomkins, V·Prest. W. R. Foutz, 'I'rc!ts. The Lewis H. Tomkins IRON ANO STEEL Hau'rl!w3.ll'e Co. OILS AND GLASS Stoves and 'rinware. Powder, Fuse, Caps and Candles. 'rin an~ Sheet Iron Work. Fire Arms and Ammunition. Aspen Colorado ---'-------~._~------~--_._---. ASPEN PlUM~~~J~ Co. ~1~UTM:1~,~:~~A~~,:'N~ James C. Johnsen. Mgr. JOBBING PROMPTLY ATTENDED All Goods Pertaining to the 'llrade. Estimates given free. PIPE AND FITTINGS .. _1~~South Mill St. __ .__Phone 40~~e_~___~sJlell,-c,o~0l'adG Aspen Bottling Works, Hawkins Bonnell & Andiu, groceries. & Bascom props. Bourquin A.mos, mining and iT; ASPOl} Commcl'eiaJ Club, Cllas vestments. Daily Sec. Boyer J.1ce' C, express. i\SPEN (JOMMISSION CO, Henry Breach A, shoemaker. lToltheer prop. BROWN DR C, pres Aspen Stall Aspen Democrat. '!'imcH (w), Chas Bank. Daily mgr. Brown IJ A VY, real estate. Aspen Drug Co, W K Hanson prop Bruin AIrs P, millinery. Aspen F'nel Co, D 1~ Hughes mgI'. 13n1't Housc, lVII's Fanny Hnff pro; Aspen Novelty Wad,", Ben Black· Byron J A, hakery, grocer. -

Department Stores on Sale: an Antitrust Quandary Mark D

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary Mark D. Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. Bauer, Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bauer: Department Stores on Sale: An Antitrust Quandary DEPARTMENT STORES ON SALE: AN ANTITRUST QUANDARY Mark D. BauerBauer*• INTRODUCTION Department stores occupy a unique role in American society. With memories of trips to see Santa Claus, Christmas window displays, holiday parades or Fourth of July fIreworks,fireworks, department storesstores- particularly the old downtown stores-are often more likely to courthouse.' engender civic pride than a city hall building or a courthouse. I Department store companies have traditionally been among the strongest contributors to local civic charities, such as museums or symphonies. In many towns, the department store is the primary downtown activity generator and an important focus of urban renewal plans. The closing of a department store is generally considered a devastating blow to a downtown, or even to a suburban shopping mall. Many people feel connected to and vested in their hometown department store.