Herbert Bayer and the Dilemma of Architectural Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL UPDATE Winter 2019

ANNUAL UPDATE winter 2019 970.925.3721 | aspenhistory.org @historyaspen OUR COLLECTIVE ROOTS ZUPANCIS HOMESTEAD AT HOLDEN/MAROLT MINING & RANCHING MUSEUM At the 2018 annual Holden/Marolt Hoedown, Archive Building, which garnered two prestigious honors in 2018 for Aspen’s city council proclaimed June 12th “Carl its renovation: the City of Aspen’s Historic Preservation Commission’s Bergman Day” in honor of a lifetime AHS annual Elizabeth Paepcke Award, recognizing projects that made an trustee who was instrumental in creating the outstanding contribution to historic preservation in Aspen; and the Holden/Marolt Mining & Ranching Museum. regional Caroline Bancroft History Project Award given annually by More than 300 community members gathered to History Colorado to honor significant contributions to the advancement remember Carl and enjoy a picnic and good-old- of Colorado history. Thanks to a marked increase in archive donations fashioned fun in his beloved place. over the past few years, the Collection surpassed 63,000 items in 2018, with an ever-growing online collection at archiveaspen.org. On that day, at the site of Pitkin County’s largest industrial enterprise in history, it was easy to see why AHS stewards your stories to foster a sense of community and this community supports Aspen Historical Society’s encourage a vested and informed interest in the future of this special work. Like Carl, the community understands that place. It is our privilege to do this work and we thank you for your Significant progress has been made on the renovation and restoration of three historic structures moved places tell the story of the people, the industries, and support. -

Bauhaus Weimar Dessau Berlin Chicago Shreveport

weimar bauhaus dessau berlin chicago shreveport modernism101.com rare design books 2012 catalog modernism101.com The Road to Utopia is easy to find if you know how to read the signs. In the United States the road ran through Boston out to the colonial suburbs of Lincoln, then down to New Canaan and New York City. It dominated the Philadelphia skyline for years. The road detoured south- ward through Asheville and the Blue Ridge Mountains, and is still readily apparent radiating outward from Chicago. The Road to Utopia was the route of the Bauhaus immigrants and aco- lytes spreading the idea — “Art and Technology: A New Unity!” — throughout the New World. Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in 1919 Weimar to reconcile the disparity between the craftsman tradition and machine age mass-production. Gropius gathered the cream of the European Avant-Garde to his cause — visionaries with names like Wassily, Oskar, Marcel, László and Farkas. These visionaries believed in Utopia, political and social perfection. The political and social systems of the era failed to reciprocate. The United States, slowly recovering from the deprivations of the Great Depression, provided fertile soil for these Utopians as the lights slowly and surely went out all over Europe. The central thesis of this catalog is that American culture was forever changed by the immigrants who fled Europe before World War II. All aspects of American culture — art, ar- chitecture, design, advertising, photography, film — were infinitely en- riched by these fugitives’ ideals. I merged onto the Road to Utopia during a visit to the Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts. -

Hebrew Type Design in the Context of the Book Art Movement and New

Philipp Messner Hebrew Type Design in the Context of the Book Art Movement and New Typography "New Book Art" ("Neue Buchkunst") was the motto under which efforts were made, in the spirit of the English Arts and Crafts Movement, toward the revival of book and type design in turn-of-the-twentieth century Germany. This revival movement perceived itself as a reaction to the country's accelerated industrialization, especially since the founding of the Reich in 1871. The replacement of traditional craft by increasingly industrial production lines effected a variety of everyday consumer products, including the manufacturing of books. According to contemporary commentators this led to deterioration in the material and aesthetic quality of books. Similarly to other industrially manufactured products around the turn of the century, an expectation emerged for books to have a contemporary, functional, and materially sound form. This demand encompassed all aspects of the book, including printing types. Consequently, visual artists were now engaged to design typefaces. Early examples were still heavily influenced by Art Nouveau, but after World War I there was a turn to historical forms with a bias toward handwritten scripts. This was influenced largely by the English calligrapher and type designer Edward Johnston, who taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London. His calligraphic method, which he based on old handwriting forms, became famous in Germany, in part thanks to the work of his pupil and translator, Anna Simons. Type design issues thus received a notably traditional treatment, defined above all by intensive engagement with historical forms. This tendency largely defined the personal styles of Franzisca Baruch and Henri Friedlaender. -

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019

Jan Tschichold and the New Typography Graphic Design Between the World Wars February 14–July 7, 2019 Jan Tschichold. Die Frau ohne Namen (The Woman Without a Name) poster, 1927. Printed by Gebrüder Obpacher AG, Munich. Photolithograph. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Peter Stone Poster Fund. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Jan Tschichold and the New February 14– Typography: Graphic Design July 7, 2019 Between the World Wars Jan Tschichold and the New Typography: Graphic Design Between the World Wars, a Bard Graduate Center Focus Project on view from February 14 through July 7, 2019, explores the influence of typographer and graphic designer Jan Tschichold (pronounced yahn chih-kold; 1902-1974), who was instrumental in defining “The New Typography,” the movement in Weimar Germany that aimed to make printed text and imagery more dynamic, more vital, and closer to the spirit of modern life. Curated by Paul Stirton, associate professor at Bard Graduate Center, the exhibition presents an overview of the most innovative graphic design from the 1920s to the early 1930s. El Lissitzky. Pro dva kvadrata (About Two Squares) by El Lissitzky, 1920. Printed by E. Haberland, Leipzig, and published by Skythen, Berlin, 1922. Letterpress. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, While writing the landmark book Die neue Typographie Jan Tschichold Collection, Gift of Philip Johnson. Digital Image © (1928), Tschichold, one of the movement’s leading The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. designers and theorists, contacted many of the fore- most practitioners of the New Typography throughout Europe and the Soviet Union and acquired a selection The New Typography is characterized by the adoption of of their finest designs. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies Collection Mss.00020

Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies collection Mss.00020 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit February 10, 2015 History Colorado. Stephen H. Hart Research Center 1200 Broadway Denver, Colorado, 80203 303-866-2305 [email protected] Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies collection Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical note................................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Accession numbers........................................................................................................................................ 9 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 -

APRIL/MAY 2011 Contemporary ART Mariine Contemporary

Caliornia APRIL/MAY 2011 Contemporary ART Mariine Contemporary Marine Contemporary Ricky Allman littlewhitehead 1733 — A Wendy Heldmann Bad News Abbot Kinney Blvd TTom Hunterer Venice, CA JoJoww Debut U.S. solo show 90291 Dennis Koch Littlewhitehead May 7 — T: +1 310 399 0294 Peter Lograsso June 18, 2011 Christopher Michlig Robert Minervini Christopher Pate Stephanie Pryor Debra Scacco marinecontemporary.com Axadra Wsfd, “Shp Trptyh”, 48 x 62", mxd mda papr, 2010 Axadra Wsfd occASSionAl beAST thrugh Apr 30, 2011 2903 Santa Monica Blvd. Santa Monica, CA 90404 310-828-1912 www.gallerykmLA.com Gallery Hours: TTue –Sat, 11am ––5pm or by appointment 30 12 25 16 29 S T Cover Image 28 N E 28 T 28 31 N 21 O 30 C 28 35 27 39 38 29 30 36 PUBLISHER Richard Kalisher EDITOR Donovan Stanley DESIGN Eric Kalisher CONTRIBUTORS 31 Roberta Carasso Jessie Kim Caliornia Contemporary ART www.caliorniacontemporaryart.net (323) 380-8916 | [email protected] 88 Apr/May 2011 EXHIBIIONS MICHAEL SALVATORE TIERNEY April 29th - May 2nd located at Chicago’s Merchandise Mart Visit us at Booth 11-B 5797 Washington Boulevard | Culver City, California 90232 | 323.272.3642 | [email protected] | blytheprojects.net EXHIBITIONS Herbert Bayer: Bauhaus by Hugo Anderson Bauhaus and our very sense o what is modern in twentieth century art and design are practically synonymous. WWe are surrounded in our everyday lives by the designs and theories put into practice by the Bauhaus. While the school o the Bauhaus existed only rom 1919 to 1933, its principals and inuence resonate today because o the achieve- ments o the artists and architects associated with it: Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky, Joseph Alpers, Lyonel Feininger, Laszlo Moholy- Nagy, Warner Drewes and Herbert Bayer. -

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019 OBJECT LIST Founding the Bauhaus Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar) 1919 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871–1956), illustrator Letterpress and woodcut on paper 850513 Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar (Idea and structure of the State Bauhaus Weimar) Munich: Bauhausverlag, 1923 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Letterpress on paper 850513 Bauhaus Seal 1919 Peter Röhl (German, 1890–1975) Relief print From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, January 1921) 850513 Bauhaus Seal Oskar Schlemmer (German, 1888–1943) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 Diagram of the Bauhaus Curriculum Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 1 The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100, Los Angeles, CA 90049 www.getty.edu German Expressionism and the Bauhaus Brochure for Arbeitsrat für Kunst Berlin (Workers’ Council for Art Berlin) 1919 Max Pechstein (German, 1881–1955) Woodcut 840131 Sketch of Majolica Cathedral 1920 Hans Poelzig (German, 1869–1936) Colored pencil and crayon on tracing paper 870640 Frühlicht Fall 1921 Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938), editor Letterpress 84-S222.no1 Hochhaus (Skyscraper) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (German, 1886–1969) Offset lithograph From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. 122–23 84-S222.no4 Ausstellungsbau in Glas mit Tageslichtkino (Exhibition building in glass with daylight cinema) Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938) Offset lithographs From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. -

UIC University Library Newsletter Fall 2018

A publication of the UIC University Library | FALL 2018 Centered on student success Library’s programs and activities crucial to helping students feel they belong on campus The University of Illinois at Chicago takes a multipronged approach to ensuring that all of its students have an equal opportunity to receive a high-quality education that prepares them to graduate and achieve their future life goals. A wide range of student success initiatives support students (especially undergraduates) in every phase of their educational progress at UIC. These include preparing students to manage their time and course loads, giving them paid internship opportunities in their fields and offering them experiences that encourage leadership development, to mention only a few. Learn more at studentsuccess.uic.edu. Participation from each of the colleges at UIC is essential to these efforts. The UIC University Library plays a unique and central role in student success because it is the only college that collaborates with and serves all of the other UIC colleges. Additionally, the Library’s physical spaces are used by more than 3.2 million visitors each year for a variety of purposes, from collaboration to quiet study, to research, classes and workshops, to events held by UIC’s academic and cultural centers and much more. The Library continually strives to cultivate partnerships and to create a welcoming and productive environment for all. NEWSLETTER The Library is currently focused on working toward three goals that support student success: 1. Instill confidence in students by giving them the knowledge, tools and resources to effectively find and evaluate information in order to complete their class assignments 2. -

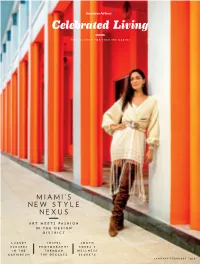

Miami's New Style Nexus

EXCLUSIVELY FOR PREMIUM CABINS MIAMI’S NEW STYLE NEXUS ART MEETS FASHION IN THE DESIGN DISTRICT LUXURY TRAVEL SOUTH ESCAPES PHOTOGRAPHY KOREA ’ S IN THE THROUGH WELLNESS CARIBBEAN THE DECADES SECRETS JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 001_COVER.rev2.indd 1 12/12/2018 16:51 Herbert Bayer’s Marble Garden, 1955, at The Aspen Institute. Below: A Bayer poster from 1951 CULTURE In 1946, Walter Paepcke, chairman of the – Container Corporation of America, brought Bayer to the former mining town to create a “Bauhaus for the corporate mind.” He designed Bauhaus The Aspen Institute, and the low-slung Aspen Meadows Resort on the campus—complete with Bertoia chairs and balcony dividers party painted red and yellow—is still like stepping To celebrate the centennial of the German into a Bauhaus wonderland. art movement, cities around the This year, The Aspen Institute is looking world—including Aspen—are mounting a back to its roots: The Bauhaus will be a subject host of exhibitions and festivals of the Aspen Ideas Festival in June, followed by a symposium in August. A Bayer exhibition ASPEN AND has been drawn from his campaign for the he original 1919 Bauhaus—a German THE BAUHAUS Container Corporation, merging artwork by art movement incorporating designers, – such luminaries as René Magritte with T artists and architects—became famous In January, the annual observations from writers like Samuel Wintersköl festival will for breaking down the distinctions between Johnson. And Bayer’s 1955 Marble Garden, an entail a Bauhaus-inspired fine and commercial art. The Bauhaus “form Wintersculpt of snow, outdoor array of marble slabs surrounding a follows function” philosophy influenced, coordinated by the influential fountain, is still a campus landmark. -

Object - Photo Report

Object - Photo Report 82.57.5 Name Moving image Photographer Kingery, Hugh Title Skiing in Colorado Non-original Title Skiing in Colorado Description Black-and-white 16mm movie on cellulose acetate film stock made circa 1950-1955, shot by Hugh Kingery. The film has not been reviewed (as of 7/16/2015) but appears to depict skiing in Colorado. The film is approximately 200 ft. in length. This film is #1 in a series of 3. Inscription The film reel in in a cardboard box with a Colorado Historical Society label. It reads: "Skiing in Colorado / 16mm film by Mr. Kingery / Gift of Mrs. Elinor Kingery / 4629 East Cedar Denver, Colorado 80222 / June 1982" ; Handwritten on label: "1982 prints" Subject Skis and skiing--Colorado, Amateur films Provenance Gift of Elinor Kingery, 1982. Collection Name Hugh M. and Elinor Kingery collection (Ph.00244) 82.57.6 Name Moving image Photographer Kingery, Hugh Title Skiing in Colorado Non-original Title Skiing in Colorado Description Black-and-white 16mm home movie on cellulose acetate film stock made circa 1950-1955, shot by Hugh Kingery. The film has not been reviewed (as of 7/16/2015) but appears to depict skiing in Colorado. The film is approximately 100 ft. in length. This film is #2 in a series of 3. Inscription The film reel in in a cardboard box with a Colorado Historical Society label. It reads: "Skiing in Colorado / 16mm film by Mr. Kingery / Gift of Mrs. Elinor Kingery / 4629 East Cedar Denver, Colorado 80222 / June 1982" ; Handwritten on label: "1982 prints" Subject Skis and skiing--Colorado Provenance Gift of Elinor Kingery, 1982. -

Leseprobe 9783791385280.Pdf

Our Bauhaus Our Bauhaus Memories of Bauhaus People Edited by Magdalena Droste and Boris Friedewald PRESTEL Munich · London · New York 7 Preface 11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those Days Photography The Idea of the at the Bauhaus Bauhaus: The Battle 16 for New Educational Josef Albers 76 Foundations Thirteen Years Howard at the Bauhaus Dearstyne 131 Mies van der Rohe’s Hans 22 Teaching at the Haffenrichter Alfred Arndt Bauhaus in Dessau Lothar Schreyer how i got to the and the Bauhaus bauhaus in weimar 83 Stage Walter Dexel 30 The Bauhaus 137 Herbert Bayer Style: a Myth Gustav Homage to Gropius Hassenpflug 89 A Look at the Bauhaus 33 Lydia Today Hannes Beckmann Driesch-Foucar Formative Years Memories of the 139 Beginnings of the Fritz Hesse 41 Dornburg Pottery Dessau Max Bill Workshop of the State and the Bauhaus the bauhaus must go on Bauhaus in Weimar, 1920–1923 145 43 Hubert Hoffmann Sándor Bortnyik 100 the revival of the Something T. Lux Feininger bauhaus after 1945 on the Bauhaus The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea 150 50 Hubert Hoffmann Marianne Brandt 117 the dessau and the Letter to the Max Gebhard moscow bauhaus Younger Generation Advertising (VKhUTEMAS) and Typography 55 at the Bauhaus 156 Hin Bredendieck Johannes Itten The Preliminary Course 121 How the Tremendous and Design Werner Graeff Influence of the The Bauhaus, Bauhaus Began 64 the De Stijl group Paul Citroen in Weimar, and the 160 Mazdaznan Constructivist Nina Kandinsky at the Bauhaus Congress of 1922 Interview 167 226 278 Felix Klee Hannes