The Great Astrolabe Reef Lagoon (Fiji)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Within 1Km Radius from the Evacuation Center Evacaution Site Location Division Province Wainaloka Church Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is

1 Population Within 1km Radius from the Evacuation Center Evacaution Site Location Division Province Wainaloka Church Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nasesara Community Hall, Motoriki Is. Motoriki Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Savuna Community Hall, Motoriki Is. Motoriki Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Tokou Community Hall, Ovalau Is. Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Naikorokoro Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Korovou Community Hall, Levuka Levuka, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Ovalau Eastern Lomaiviti Levuka Vakaviti Community Hall, Levuka Levuka, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Ovalau Eastern Lomaiviti Taviya Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Waitovu Community Hall, Ovalau Is. Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Somosomo Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Sawaieke Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nawaikama Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Lovu Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Lamiti Village Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vanuaso Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nacavanadi Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vadravadra Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Kade Community Hall, Koro Is. Koro Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Viti-Levu Eastern Lomaiviti Tovulailai Community Hall, Nairai Is. Nairai Is. Lomaiviti Grp, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vagadaci Village Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vuma Village Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. -

BA Amendments

UPDATES TO ADMIRALTY LIST OF LIGHTS AND FOG SIGNALS Vol K Edition 2015/16. Weekly Edition No. 19, Dated 07 May 2015. Last Updates: Weekly Edition No. 18, dated 30 April 2015. K1257·3 - Tanjungwangi Harbour 8 08·09 S Q(4)W 8s 10 ID, , 4041A (Meneng). Harbour 114 24·08 E (ID) ******** SELAT BALI. BALI K1258 Remove from list; deleted SELAT BALI. BALI K1258·1 Remove from list; deleted HAURAKI GULF. THE NOISES. RAKINO ISLAND K3742·2 Remove from list; deleted 5.9 Wk19/15 VI 5.+4,$ -/ /TAKHRGDC6J +@RS4OC@SDR6DDJKX$CHSHNM-N C@SDC OQHK 1 # 1!$ ".-2 / &$ !1 9(+ ADKNV/NMS@/HQ@ITA@+S (MRDQS ,@MNDK+T§R+S%KN@S!% mț̦2mț̦6 m 3 !Q@YHKH@M-NSHBD12#1 43., 3("(#$-3(%(" 3(.-2823$, (2 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'DMFWHM6QDBJ (MRDQS 'NMF8T@M mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 5HQST@K ENQLDQTOC@SD "GHMDRD-NSHBD12#1 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'T@MFYD8@MF+S5DRRDK (MRDQS 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR -

Survival Guide on the Road

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd PAGE ON THE YOUR COMPLETE DESTINATION GUIDE 42 In-depth reviews, detailed listings ROAD and insider tips Vanua Levu & Taveuni p150 The Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups p112 Ovalau & the Lomaiviti Group Nadi, Suva & Viti Levu p137 p44 Kadavu, Lau & Moala Groups p181 PAGE SURVIVAL VITAL PRACTICAL INFORMATION TO 223 GUIDE HELP YOU HAVE A SMOOTH TRIP Directory A–Z .................. 224 Transport ......................... 232 Directory Language ......................... 240 student-travel agencies A–Z discounts on internatio airfares to full-time stu who have an Internatio Post offices 8am to 4pm Student Identity Card ( Accommodation Monday to Friday and 8am Application forms are a Index ................................ 256 to 11.30am Saturday Five-star hotels, B&Bs, able at these travel age Restaurants lunch 11am to hostels, motels, resorts, tree- Student discounts are 2pm, dinner 6pm to 9pm houses, bungalows on the sionally given for entr or 10pm beach, campgrounds and vil- restaurants and acco lage homestays – there’s no Shops 9am to 5pm Monday dation in Fiji. You ca Map Legend ..................... 263 to Friday and 9am to 1pm the student health shortage of accommodation ptions in Fiji. See the ‘Which Saturday the University of nd?’ chapter, p 25 , for PaciÀ c (USP) in ng tips and a run-down hese options. Customs Regulations E l e c t r Visitors can leave Fiji without THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Dean Starnes, Celeste Brash, Virginia Jealous “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Get the right guides for your trip PAGE PLAN YOUR PLANNING TOOL KIT 2 Photos, itineraries, lists and suggestions YOUR TRIP to help you put together your perfect trip Welcome to Fiji ............... -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Opportunity to Explore the Speciation

Odonatologica37(3): 235-245 September 1. 2008 The Fijian Nesobasis: a further examination of species diversity and abundance (Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae) H. Van Gossum¹’*,C.D. Beatty²,M. Tokota’a³ andT.N. Sherratt4 1 Evolutionary Ecology Group, University of Antwerp, Groenenborgerlaan 171, B-2020 Antwerp, Belgium 2 de de Grupo Ecologia Evolutiva, Departaraento Ecologia y BiologiaAnimal, Universidad de Vigo, EUET Forestal, Campus Universitario, ES-36005 Pontevedra, Galicia, Spain 3 International Conservation, South Pacific Program, 11 Ma’afu Street, Suva, Fiji 4 Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5B6, Canada Received June 11, 2007 / Reviewed and AcceptedOctober 21, 2007 Recently, an overview of the diversity, abundance, distribution and morphological characteristics of spp. of the genus Nesobasis endemic to Fiji, was presented for , spp. occurring on the 2 largest islands of the archipelago: Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. Here, this knowledge is extended by providing more extensive diversity and abundance data for the island of Vanua Levu, as well as for 4 smaller islands in Fiji: Taveuni, Koro, Ovalau and Kadavu. Previous research indicated that the Nesobasis spp. inhabiting Viti Levu and Vanua Levu are unique, with these islands having no species in com- The data confirm this and also show that smaller islands in mon. new proposal prox- imity to these 2 larger islands usually contain a subset of the large island’s Nesobasis fauna. The island of Koro, however, is unusual in that, while its Nesobasis spp. are Vanua N. predominantlythose found on Levu, it also harbours rufostigma, a sp. oc- curring on Viti Levu. -

Leaving Place, Restoring Home Enhancing the Evidence Base on Planned Relocation Cases in the Context of Hazards, Disasters, and Climate Change

LEAVING PLACE, RESTORING HOME ENHANCING THE EVIDENCE BASE ON PLANNED RELOCATION CASES IN THE CONTEXT OF HAZARDS, DISASTERS, AND CLIMATE CHANGE By Erica Bower & Sanjula Weerasinghe March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and feedback of several individuals and organizations in the preparation of this report. This includes members of the reference group: colleagues at the Platform on Disaster Displacement (Professor Walter Kälin, Sarah Koeltzow, Juan Carlos Mendez and Atle Solberg); members of the Platform on Disaster Displacement Advisory Committee including Bruce Burson (Independent Consultant), Beth Ferris (Georgetown University), Jane McAdam (UNSW Sydney) and Matthew Scott (Raoul Wallenberg Institute); colleagues at the International Organization for Migration (Alice Baillat, Pablo Escribano, Lorenzo Guadagno and Ileana Sinziana Puscas); colleagues at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Florence Geoffrey, Isabelle Michal and Michelle Yonetani); and colleagues at GIZ (Thomas Lennartz and Felix Ries). The authors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Julia Goolsby, Sophie Offner and Chloe Schalit. This report has been carried out under the Platform on Disaster Displacement Work Plan 2019-2022 with generous funding support from the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland. It was co-commissioned by the Platform on Disaster Displacement and the Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW Sydney. Any feedback or questions about this report may -

A Guide to the Common Edible and Medical Sea Plants of the Pacific

SFKL. SECRETARIAT OF THE PACIFIC COMMUNITY A Guide to the Common Edible and Medicinal Sea Plants of the Pacific Islands By Dr Irene Novaczek Community Fisheries Training Pacific Series 3A Supplementary Guide to Sea Plants: Pacific Series 3 USP Marine Studies Programme / SPC Coastal Fisheries Programme: Training Materials for Pacific Community Fisheries The University of the South Pacific Secretariat of the Pacific Community Canada-South Pacific Ocean Development New Zealand Official Development Assistance Australian Agency for International Development International Ocean Institute - Pacific Islands ^HCoc NZODA ^ c.sp0© SPC Library 34518 Bibliotheque CPS A Guide to the Common Edible and Medicinal Sea Plants of the Pacific Islands © USP Marine Studies Programme / Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2001 All rights for commercial / profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. The USP and SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that the USP, SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Novaczek, Irene A Guide to the Common and Edible and Medicinal Sea Plants of the Pacific Islands/Irene Novaczek (Community Fisheries Training Pacific Series / University of the South Pacific, Secretariat of the -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

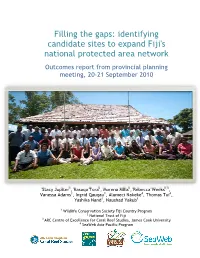

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses. -

Status of Coral Reefs in the Fiji Islands 2007

COMPONENT 2A - Project 2A2 Knowledge, monitoring, management and beneficial use of coral reef ecosystems January 2009 REEF MONITORING SOUTH-WEST PACIFIC STATUS OF CORAL REEFS REPORT 2007 Edited by Cherrie WHIPPY-MORRIS Institute of Marine Resources With the support of: Photo: E. CLUA The CRISP programme is implemented as part of the Regional Environment Programme for a contribution to conservation and sustainable development of coral T (CRISP), sponsored by France and prepared by the French Development Agency (AFD) as part of an inter-ministerial project from 2002 onwards, aims to develop a vi- sion for the future of these unique eco-systems and the communities that depend on them and to introduce strategies and projects to conserve their biodiversity, while developing the economic and environmental services that they provide both locally and globally. Also, it is designed as a factor for integration between developed coun- - land developing countries. The CRISP Programme comprises three major components, which are: Component 1A: Integrated Coastal Management and watershed management - 1A1: Marine biodiversity conservation planning - 1A2: Marine Protected Areas - 1A3: Institutional strengthening and networking - 1A4: Integrated coastal reef zone and watershed management CRISP Coordinating Unit (CCU) Component 2: Development of Coral Ecosystems Programme manager : Eric CLUA - 2A: Knowledge, monitoring and management of coral reef ecosytems SPC - PoBox D5 - 2B: Reef rehabilitation 98848 Noumea Cedex - 2C: Development of active marine substances -

Insights and Regrets of a Foreign Geoscientist in the Pacific Islands

geosciences Article O cei na Vulavula? Insights and Regrets of a Foreign Geoscientist in the Pacific Islands Patrick D. Nunn School of Law and Society, Australian Centre for Pacific Islands Research, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, QLD 4558, Australia; [email protected] Abstract: From over three decades of close contact with Pacific Islands geoscience, the author reflects on key issues (what he wished he had known earlier) about the nature of islands, their landscapes and their peoples. Experience elsewhere in the world rarely prepares you for the Pacific, from its youthful and often tectonically unstable landscapes to the understandings of its inhabitants, which are sometimes time-consuming and difficult to access yet frequently illuminating. Mysteries abound in Pacific geoscience, often in places as difficult to access as they ever were, yet which have the potential to inform global ideas about earth-surface evolution. Geoscience research and enterprise remain largely foreigner-driven in the Pacific Islands, which is often anathemic to sustainability, privileging ideas that are uncritically assumed to be shared by their peoples. An opportunity exists for Pacific peoples to own the geoscientific knowledge and potential of their islands. Keywords: Pacific; knowledge; island geology; traditions; last interglacial; sea-level change; island flank collapse; lithospheric flexure; radiocarbon dating Citation: Nunn, P.D. O cei na Vulavula? Insights and Regrets of a 1. Background Foreign Geoscientist in the Pacific A few days after I arrived in Fiji, so did Eric and Nigel, the first tropical cyclones to hit Islands. Geosciences 2021, 11, 182. Suva directly in more than forty years.