Moturiki, Lomaiviti Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Within 1Km Radius from the Evacuation Center Evacaution Site Location Division Province Wainaloka Church Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is

1 Population Within 1km Radius from the Evacuation Center Evacaution Site Location Division Province Wainaloka Church Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nasesara Community Hall, Motoriki Is. Motoriki Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Savuna Community Hall, Motoriki Is. Motoriki Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Tokou Community Hall, Ovalau Is. Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Naikorokoro Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Korovou Community Hall, Levuka Levuka, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Ovalau Eastern Lomaiviti Levuka Vakaviti Community Hall, Levuka Levuka, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Ovalau Eastern Lomaiviti Taviya Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Waitovu Community Hall, Ovalau Is. Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Somosomo Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Sawaieke Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nawaikama Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Lovu Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Lamiti Village Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vanuaso Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nacavanadi Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vadravadra Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Kade Community Hall, Koro Is. Koro Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Viti-Levu Eastern Lomaiviti Tovulailai Community Hall, Nairai Is. Nairai Is. Lomaiviti Grp, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vagadaci Village Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vuma Village Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Reef Check Description of the 2000 Mass Coral Beaching Event in Fiji with Reference to the South Pacific

REEF CHECK DESCRIPTION OF THE 2000 MASS CORAL BEACHING EVENT IN FIJI WITH REFERENCE TO THE SOUTH PACIFIC Edward R. Lovell Biological Consultants, Fiji March, 2000 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 2.0 Methods.........................................................................................................................................4 3.0 The Bleaching Event .....................................................................................................................5 3.1 Background ................................................................................................................................5 3.2 South Pacific Context................................................................................................................6 3.2.1 Degree Heating Weeks.......................................................................................................6 3.3 Assessment ..............................................................................................................................11 3.4 Aerial flight .............................................................................................................................11 4.0 Survey Sites.................................................................................................................................13 4.1 Northern Vanua Levu Survey..................................................................................................13 -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Opportunity to Explore the Speciation

Odonatologica37(3): 235-245 September 1. 2008 The Fijian Nesobasis: a further examination of species diversity and abundance (Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae) H. Van Gossum¹’*,C.D. Beatty²,M. Tokota’a³ andT.N. Sherratt4 1 Evolutionary Ecology Group, University of Antwerp, Groenenborgerlaan 171, B-2020 Antwerp, Belgium 2 de de Grupo Ecologia Evolutiva, Departaraento Ecologia y BiologiaAnimal, Universidad de Vigo, EUET Forestal, Campus Universitario, ES-36005 Pontevedra, Galicia, Spain 3 International Conservation, South Pacific Program, 11 Ma’afu Street, Suva, Fiji 4 Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5B6, Canada Received June 11, 2007 / Reviewed and AcceptedOctober 21, 2007 Recently, an overview of the diversity, abundance, distribution and morphological characteristics of spp. of the genus Nesobasis endemic to Fiji, was presented for , spp. occurring on the 2 largest islands of the archipelago: Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. Here, this knowledge is extended by providing more extensive diversity and abundance data for the island of Vanua Levu, as well as for 4 smaller islands in Fiji: Taveuni, Koro, Ovalau and Kadavu. Previous research indicated that the Nesobasis spp. inhabiting Viti Levu and Vanua Levu are unique, with these islands having no species in com- The data confirm this and also show that smaller islands in mon. new proposal prox- imity to these 2 larger islands usually contain a subset of the large island’s Nesobasis fauna. The island of Koro, however, is unusual in that, while its Nesobasis spp. are Vanua N. predominantlythose found on Levu, it also harbours rufostigma, a sp. oc- curring on Viti Levu. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Ministry of Health and Medical Services

1 MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND MEDICAL SERVICES January –July Report 2016 December 2016 Hon Rosy Akbar The Minister for Health and Medical Services Ministry of Health and Medical Services Suva Dear Hon Akbar, I am pleased to submit the January-July Report 2016 in accordance with the Government’s regulatory requirements. 2 Contents 1. Permanent Secretary’s Remarks .................................................................................... 7 2. Ministry of Health and Medical Services Overview........................................................ 8 3. Ministry of Health and Medical Services Priorities ......................................................... 8 Guiding Principles....................................................................................................... 9 Key Cabinet Papers.................................................................................................... 11 4. Reporting on SDGs January -July 2016 ........................................................................ 13 5. Impact of Tropical Cyclone Winston on Planned Activities ........................................... 15 6. Hospital Services ....................................................................................................... 16 7. Fiji Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Services Centre (FPBSC) .......................................... 18 8. Divisional Report ..................................................................................................... 20 9. Public Health Services .............................................................................................. -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

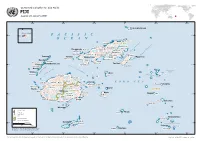

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

P a C I F I C O C E

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific FIJI Issued: 20 January 2008 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W Thikombia Island 177° Nalele Rotuma Island 16°S PACIFIC 16°S 12°30’ Rotuma Sumi OCEAN Namukalau Nambouono Vunivatu NORTHERN Nanduri Namboutini Nayarambale Napuka Yangganga Navindamu Labasa Nailou Yangganga Rabi Channel Korotasere Nakarambo Savu Sau Nawailevu Taveun i Mate i Vanuabalavu Riqold Channel Mbangasau t i Matei Yasawa a Yandua r Nggamea Vanua Levu t Qeleni Cicia S Ndenimanu o Nacula Ndaria o m o s Waiyevo Navotua Waisa m S o Matacawalevu Matathawa Levu Rave-rave Taveuni 17°S Yaqeta VATU-I-RA CHANNELThavanga 17°S Somosomo Navakawau UP RO Naviti G A W A EXPLORING S Waya S ISLES A Y Koro Nalauwaki NORT Thikombia BLIGH WATER Togow ere Koro HERN LAU Tavua Makongai GRO Nasau UP Nayavutoka Vanuakula Lautoka Navala Navai Ovalau KORO SEA Bureta Levuka Tu vu th a Tuvutha Mala WESTERN Nayavu Lawaki Malololailai Nadi Wairuarua Lovoni Bukuya Nairai Malolo Vunindawa Saweni Korovou EASTERN Momi Viti Levu CENTRAL Narewa Dromuna Ngau 18°S Naraiyawa Nayau Liku 18°S Namosi Nausori Bega Ngau Sigatoka Navua Vatukarasa SUVA e Levuka Lakemba ssag Pa qa Vanuavatu Be Waisomo Mbengga National Capital City, Town Moala Moala Major Airport River Namuka Llau Provincial Boundary Namuka International Boundary Vabea 0 20 40 Kilometers Kandavu 19°S Soso 19°S Nukuvou SOUTHERN LAU GROUP 0 20 40 Miles Kandavu Fulanga Ongea Projection: World Cylindrical Equal Area Nasau Andako Matuku Monothaki Map data sources: Global Discovery, FAO 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W The names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Map Ref: OCHA_FJI_Country_v1_080120. -

TA31 Book.Indb 231 24/11/09 12:13:40 PM 232 Trevor H

10 Bird, mammal and reptile remains Trevor H. Worthy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of New South Wales Geoffrey Clark Department of Archaeology and Natural History, The Australian National University Introduction This chapter reports the non-fish remains from 10 archaeological excavations on Viti Levu and the Lau Group, including the reanalysis of a bird-bone assemblage from Lakeba Island excavated previously by Simon Best (1984). Bone remains from Natunuku and Ugaga were uncommon and the small assemblages were misplaced during collection relocation after bushfires destroyed the ANU archaeological storage facility in 2003, and these assemblages are not considered further. Three of the non-fish faunal assemblages are from the Lau Group (Qaranipuqa, Votua, Sovanibeka), one is from the north coast of Viti Levu (Navatu 17A), and the remainder are from the southwest Viti Levu region (Malaqereqere, Tuvu, Volivoli II, Volivoli III, Qaraninoso II) and Beqa Island (Kulu). This chapter presents the non-fish fauna from the Lau Group, followed by that from Viti Levu and Beqa Island. Faunal analysis began early in Fiji, with bone remains identified at Navatu and Vuda on Viti Levu by Gifford (1951:208–213). Gifford’s excavations demonstrated that pig, dog, chicken, turtle, fruit bat and humans were consumed during the ‘early period’ of Fiji. The study of archaeofauna declined after this promising start due to the absence of prehistoric fauna in sites such as Sigatoka and Karobo (Palmer 1965; Birks 1973), and the cursory identification of bone remains at sites like Yanuca and Natunuku (Birks and Birks 1978; Davidson et al. -

Republic of Fiji: the State of the World's Forest Genetic Resources

REPUBLIC OF FIJI This country report is prepared as a contribution to the FAO publication, The Report on the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources. The content and the structure are in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines given by FAO in the document Guidelines for Preparation of Country Reports for the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources (2010). These guidelines set out recommendations for the objective, scope and structure of the country reports. Countries were requested to consider the current state of knowledge of forest genetic diversity, including: Between and within species diversity List of priority species; their roles and values and importance List of threatened/endangered species Threats, opportunities and challenges for the conservation, use and development of forest genetic resources These reports were submitted to FAO as official government documents. The report is presented on www. fao.org/documents as supportive and contextual information to be used in conjunction with other documentation on world forest genetic resources. The content and the views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the entity submitting the report to FAO. FAO may not be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this report. STATE OF THE FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES IN FIJI Department of Forests Ministry of Fisheries and Forests for The Republic of Fiji Islands and the Secreatriat of Pacific Communities (SPC) State of the Forest Genetic Resources in Fiji _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Executve Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 5 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 6 Chapter 1: The Current State of the Forest Genetic Resources in Fiji ………………………………………………………………….…….