The Evolution of the New Federal Women's Prisons in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assiniboia - Estevan

FIRMS / OFFICES / CORPORATE COUNSEL ASSINIBOIA - ESTEVAN BUFFALO NARROWS ASSINIBOIA 306-235-4489 CHARTIER, CLEMENT J. 306-642-4520 FORD, KIMBERLEY Fax: 613-720-9649 PO Box 361 Fax: 306-642-5777 M. LAW PC LTD. Buffalo Narrows, SK S0M 0J0 228 Centre Street Clement J. CHARTIER, QC (1980) PO Box 759 Assiniboia, SK S0H 0B0 Email: [email protected] † Kimberley M. FORD (1984) CUTKNIFE 306-642-3866 MOUNTAIN & MOUNTAIN LAW FIRM 306-490-8161 KASOKEO LAW Fax: 306-642-5848 101 - 4th Avenue West Fax: 306-937-6110 PO Box 2 PO Box 459 Cutknife, SK S0M 0N0 Assiniboia, SK S0H 0B0 Deanne K. KASOKEO (2009) Email: [email protected] Web: http://mounl.sasktelwebsite.net † Thomas V. MOUNTAIN (1978) † L. Lee MOUNTAIN (1979) DAVIDSON 306-567-5554 DELLENE CHURCH LAW OFFICE Fax: 306-567-5554 200 Garfield St Box 724 BATTLEFORD Davidson, SK S0G 1A0 306-490-7765 DANIELS, TANNER J. Email: [email protected] Fax: 306-937-0002 161 - 29th Street Dellene S. CHURCH (1995) PO Box 242 Cindy D. DOLAN (2015) Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Cody GIENI (2019) 306-937-6154 SUNCHILD LAW 306-567-2023 SHIRKEY LAW OFFICE Fax: 306-937-6110 PO Box 1408 Fax: 306-567-4223 127 Washington Avenue Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 PO Box 280 Email: [email protected] Davidson, SK S0G 1A0 Email: [email protected] † Eleanore K. SUNCHILD (1999) Michael J. SEED (2017) † Daryl A. SHIRKEY (1976) BIGGAR ESTERHAZY 306-948-3346 BUSSE LAW PROFESSIONAL 306-745-3952 BOCK AND COMPANY LAW OFFICE Fax: 306-948-3366 CORPORATION Fax: 306-745-6119 500 Maple Street 302 Main Street PO Box 220 PO Box 669 Esterhazy, SK S0A 0X0 Biggar, SK S0K 0M0 † Lynnette E. -

Overview of Indigenous Services Canada Initiatives

Annex 8 OVERVIEW OF INDIGENOUS SERVICES CANADA INITIATIVES FOR THE INFORMATION OF THE COMMISSIONERS OF THE NATIONAL INQUIRY INTO MISSING AND MURDERED INDIGENOUS WOMEN AND GIRLS Introduction Housing is a fundamental need and all Canadians, including Indigenous peoples, should have access to adequate, safe and affordable housing. Nearly one in five Indigenous people live in housing in need of major repairs, and one in five also live in overcrowded housing.1 It is understood that overcrowding and poor housing conditions can be a contributing factor to family violence, sometimes causing people to leave their communities. Households in Canada’s north, particularly Inuit women and girls, are more likely to be in core housing need and face the most crowded living conditions in all of Canada. This situation contributes to homelessness, particularly among Inuit women, and has a direct negative impact on a number of health concerns such as family violence, respiratory illnesses, and children’s ability to learn. Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) work collaboratively with partners, including the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), to improve access to high quality services for First Nations, Inuit and Métis. The Government of Canada’s vision is to support and empower Indigenous peoples to independently deliver services and address the needs and challenges in their communities. ISC welcomes the opportunity to share its initiatives in this area with Commissioners of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (the Inquiry), and will focus on what we are providing now along the housing continuum, and our plans going forward, to support better outcomes for Indigenous peoples, particularly women and girls. -

First Nations University of Canada Governance Plan

M.A. Begay II & Associates, LLC 3421 West Foxes Meadow Email: [email protected] Drive Tuscon, AZ 85745 USA First Nations University of Canada Governance Plan First Nations University of Canada Governance Plan An Opportunity to Lead the World in First Nations Higher Education MAB II & Associates, LLC Page ii 2/17/10 . 1 Table of Contents. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS..........................................................................................................................III 2 INDEX OF FIGURES..............................................................................................................................VII 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................................9 3.1.1 Overall Recommendation:...............................................................................................................................11 3.1.1.1 The Nominating Committee......................................................................................................................................................12 3.1.1.2 The Board .........................................................................................................................................................................................12 3.1.1.3 Board Principles and Subcommittees ..................................................................................................................................14 3.1.1.4 Board Compensation ...................................................................................................................................................................16 -

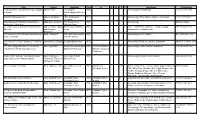

Title Author Publisher Date in V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number

Title Author Publisher Date In V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number Field Manual for Avocational Archaeologists Adams, Nick The Ontario 1994 1 Archaeology, Methodology CC75.5 .A32 1994 in Ontario Archaeological Society Inc. Prehistoric Mesoamerica Adams, Richard E. Little, Brown and 1977 1 Archaeology, Aztec, Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan F1219 .A22 1991 W. Company Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Addington, Lucile R. The University of 1986 Archaeology 000Unavailable Artifacts for Publication Chicago Press The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North Adney, Edwin Tappan Smithsonian Institution 1983 1 Form, Construction, Maritime, Central Canada, E98 .B6 A46 1983 America and Howard I. Press Northwestern Canada, Arctic Chappelle The Knife River Flint Quarries: Excavations Ahler, Stanley A. State Historical Society 1986 1 Archaeology, Lithic, Quarry E78 .N75 A28 1986 at Site 32DU508 of North Dakota The Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Tassili N' Mazonowicz, Douglas Douglas Mazonowicz 1970 1 Archaeology, Rock Art, Sahara, Sandstone N5310.5 .T3 M39 1970 Ajjer The Archeology of Beaver Creek Shelter Alex, Lynn Marie Rocky Mountain Region 1991 Selections form the 3 1 Archaeology, South Dakota, Excavation E78 .S63 A38 1991 (39CU779): A Preliminary Statement National Park Service Division of Cultural Resources People of the Willows: The Prehistory and Ahler, Stanley A., University of North 1991 1 Archaeology, Mandan, North Dakota E99 .H6 A36 1991 Early History of the Hidatsa Indians Thomas D. Thiessen, Dakota Press Michael K. Trimble Archaeological Chemistry -

Appendix D: Groups Included in Secondary Outreach Phase

Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Certificate OC-063 - Condition 12 Line 3 Replacement Program Aboriginal Monitoring Plan Appendix D Appendix D: Groups Included in Secondary Outreach Phase Agency Chiefs Tribal Council Mosquito Grizzly Bear's Head, Lean Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation Man First Nation Alexander First Nation Mountain Cree Asini Wachi Nehiyawak Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation Muscowpetung First Nation Assembly of First Nations Muskeg Lake Cree Nation Assembly of First Nations - Alberta Muskowekwan First Nation Region Nekaneet First Nation Assembly of First Nations - Manitoba O-Chi-Chak-ko-Sipi (Crane River) First Region Nation Assembly of First Nations - Ocean Man First Nation Saskatchewan Region Ochapowace First Nation Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Okanese First Nation Battlefords Tribal Council One Arrow First Nation Battleford Agency Tribal Chiefs Onion Lake Cree Nation Beardy’s & Okemasis First Nation Papaschase First Nation Bearspaw First Nation Pasqua First Nation Beaver Lake Cree Nation Paul First Nation Big Island Lake Cree Nation Peepeekisis First Nation Big River First Nation Peguis First Nation Birdtail Sioux Dakota First Nation Pelican Lake Brokenhead Ojibway First Nation Pheasant Rump Nakota First Nation Buffalo Point First Nation Piapot First Nation Canupawakpa Dakota Nation Piikani Nation Carry the Kettle First Nation Pinaymootang First Nation Central Urban Métis Federation Inc. Pine Creek First Nation Chief Big Bear First Nation Poundmaker Cree Nation Chiniki First Nation Red Pheasant -

Saskatchewan Official Road

PRINCE ALBERT MELFORT MEADOW LAKE Population MEADOW LAKE PROVINCIAL PARK Population 35,926 Population 40 km 5,992 5,344 Prince Albert Visitor Information Centre Visitor Information 4 3700 - 2nd Avenue West Prince Albert National Park / Waskesieu Nipawin 142 km Northern Lights Palace Meadow Lake Tourist Information Centre Phone: 306-682-0094 La Ronge 88 km Choiceland and Hanson Lake Road Open seasonally 110 Mcleod Avenue W 79 km Hwy 4 and 9th Ave W GREEN LAKE 239 km 55 Phone: 306-752-7200 Phone: 306-236-4447 ve E 49 km Flin Flon t A Chamber of Commerce 6 RCMP 1s 425 km Open year-round 2nd Ave W 3700 - 2nd Avenue West t r S P.O. Phone: 306-764-6222 3 e iv M e R 5th Ave W r e Prince Albert . t Open year-round e l e n c f E v o W ru e t p 95 km r A 7th Ave W t S C S t y S d Airport 3 Km 9th Ave W H a 5 r w 3 Little Red 55 d ? R North Battleford T River Park a Meadow Lake C CANAM o Radio Stations: r HIGHWAY Lions Regional Park 208 km 15th St. N.W. 15th St. N.E. Veteran’s Way B McDonald Ave. C CJNS-Q98-FM e RCMP v 3 Mall r 55 . A e 3 e Meadow Lake h h v RCMP ek t St. t 5 km Northern 5 A Golf Club 8 AN P W Lights H ark . E Airport e e H Ave. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. , 98 394-2-43 E?2 2005 Evaluation Framework of the Assessment of the Nekaneet First Nation Capacity to enter into CCRA Section 81 with the Correctional Service of Canada Evaluation & Review Branch Performance Assurance Correctional Servicel January 20, 2005 of Canada 2008 FEB 0 4 Okirnaw Ohci Healingi Leckie LIBRARY / BIBLIOTHÈQUE PSEPC/SPPCC 98 .C87 JAN 1 0 2008 E92 2005 OTTAWA (ONTARIO) KIA OP8. -

Bulletin to First Nations in Saskatchewan

Bulletin to First Nations in Saskatchewan As with any other communicable disease in First Nations communities in Saskatchewan, public health follow-up and management of COVID-19 cases and contacts is coordinated by Indigenous Services Canada for south and central First Nations communities and by the Northern Inter-tribal Health Authority (NITHA) for the northern First Nations communities. Status Update As of May 21, Saskatchewan has officially reported 622 cases of COVID-19. As of May 21, 42,443 COVID-19 tests have been performed in Saskatchewan. Summary of Persons with COVID-19 in Saskatchewan Cases and Risk of COVID-19 in Saskatchewan Total Confirmed * Active Inpatient ICU Region Recovered Deaths Cases Cases Cases Hospitalization Hospitalizations Far North 244 244 93 0 0 150 1 North 110 110 6 0 0 102 2 Central 12 12 1 0 0 10 1 (excluding Saskatoon) Saskatoon 165 165 5 1 3 158 2 South 15 15 0 0 0 15 0 (excluding Regina) Regina 76 76 1 1 0 74 1 Total Saskatchewan 622 622 106 2 3 509 7 *There may be more recovered cases yet to be reported to Public Health. Summary of COVID-19 cases in Saskatchewan First Nations Communities As of May 21, there are 48 confirmed COVID-19 cases reported in Saskatchewan First Nation communities. Fourteen out of the 48 cases are considered active. The remaining 33 cases have recovered. One First Nations (1) resident with COVID-19 has died. Individuals who are concerned about symptoms or risks related to COVID‐19 should call Healthline 811 or use the online self‐assessment tool found on the Ministry of Health website. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Healing Lodge Location Announcement Maple Creek, Saskatchewan Friday May 22, 1992 ; -,inyright of this document does not belong to the Crown. •),ioer authorization must be obtained from the author for y intended use . 2s droits d'auteur du présent document n'appartiennent à l'Étal Toute utilisation du contenu du présent ,.1.-,cument doit être approuvée préalablement par l'auteur. -

Cree Language Sounds

How to Spell it in Cree (The Standard Roman Orthography) Jean Okimásis and Arok Wolvengrey miywási n ink Copyright © 2008 Jean Okimāsis and Arok Wolvengrey Copyright Notice All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical – without the prior written permission of the publisher. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Okimāsis, Jean L. How to spell it in Cree : the standard Roman orthography / Jean Okimāsis and Arok Wolvengrey. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9784935-0-9 1. Cree language--Orthography and spelling. I. Wolvengrey, Arok. II. Title. PM987.O385 2008 497'.323152 C2008-903382-5 Cover design: miywāsin ink, oskana kā-asastēki (Regina) Printed and bound in Canada by Houghton Boston, misāskwatōminihk (Saskatoon) Table of Contents 1 Introduction......................................................................................................1 Cree and the Standard Roman Orthography 2 What Not to Use ..............................................................................................4 English Symbols...................................................................................................... 4 English Digraphs..................................................................................................... 4 English Capitalization............................................................................................. 5 Conclusion.............................................................................................................. -

Aboriginal Diabetes Projects in Canada

Aboriginal Diabetes Projects in Canada Province Name Address Activities Alberta Aboriginal Diabetes 801-1 Avenue South • Individual Sessions Prevention and Lethbridge Alberta T1J 4L5 • Group Sessions Management • Pregnancy Clinics Program Tel: 403-388-6675 • In-patient support • Insulin Initiation Program • Diabetes and Heart Classes • Blood Glucose Screening • Community Presentations • Walking Groups • Community Kitchen • Grocery Store Tours Aboriginal Diabetes 204-Anderson Hall • Organized Walks Wellness Program- 10959-102 Street • Nutrition Programs Capital Health Edmonton, Alberta • School Diabetes Programs • Awareness Promotion Tel: 780-477-4512 • Traditional Herb/Medicine Workshop • Glucose monitoring Description: 1 or 3 Day Basic Diabetes Education Program provides a holistic and cultural program for people living with Diabetes, offers the choice of traditional and /or western ways to wellness, and assists individuals to learn how to balance mind, body , emotion and spirit. Alexis First Nation Alexis First Nation • School Diabetes Program PO Box 39 • Awareness Promotion Glenevis, Alberta • Foot Care Clinics • School Breakfast/Lunch Program Tel: 780-967-2591 • Pre-Natal Education • Annual Diabetes Week Description: On-going monitoring is done on a one to one basis Atikameg Health Atikameg Health Centre • Organized Walks Centre Box 210 • Nutrition Program Atikameg Alberta • Awareness Promotion • Traditional Herb/Medicine Workshops Tel: 780-767-3941 • Foot Care Clinic • Glucose Monitoring • Pre-Natal Education Description: No information -

First Nations in the Lake Winnipeg Watershed

First Nations in the Lake Winnipeg Watershed Manitoba Berens River First Nation Poplar River First Nation Little Saskatchewan First Nation Black River First Nation Sagkeeng First Nation Long Plain First Nation Bloodvein First Nation Birdtail Sioux Dakota Nation Mosakahiken Cree Nation Brokenhead Ojibway Nation Buffalo Point First Nation O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi FirOst Nation Dauphin River First Nation Canupawakpa Dakota Nation Opaskwayak Cree Nation Fisher River Cree Nation Chemawawin Cree Nation Paunigassi First Nation Hollow Water First Nation Dakota Plains Wahpeton First Nation Pine Creek First Nation Kinonjeoshtegon First Nation Dakota Tipi First Nation Rolling River First Nation (Jackhead) Lake St. Martin First Nation Ebb and Flow First Nation Roseau River First Nation Misipawistik Cree Nation Gambler First Nation Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation Norway House Cree Nation Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Peguis First Nation Little Manitoba First Nation Skownan First Nation Pinaymootang First Nation Little Grand Rapids First Nation Swan Lake First Nation (includes (Fairford) Indian Gardens 8, Swan Lake 7, Swan Lake 7A, and Swan Lake First Nation 8A) Tootinaowaziibeeng First Nation Waywayseecappo First Nation Wuskwi Sipihk First Nation (Valley River Reserve #292) Saskatchewan Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation Beardy’s and Okemasis First Nation Big River First Nation Carry the Kettle First Nation Cote First Nation Cowessess First Nation Cumberland House Cree Nation Day Star First Nation Fishing Lake First Nation Flying Dust