Unesco's 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

2005-Winter.Pdf

HomecomingHomecoming ’05’05 WhatWhat aa Weekend!Weekend! TheThe SamfordSamford PharmacistPharmacist NewsletterNewsletter pagepage 2929 NewNew SamfordSamford ArenaArena pagepage 5656 features SEASONS 4 Why Jihad Went Global Noted Mid-East scholar Fawaz Gerges traces steps in the Jihadist movement’s decision to attack “the far enemy,” the United States and its allies, after two decades of concentrating on “the near enemy” in the Middle East. Gerges delivered the annual J. Roderick Davis Lecture. 6 Reflections on Egypt Samford French professor Mary McCullough shares observations and insights gained from her participation in a Fulbright-Hays Seminar in Egypt during the summer of 2005. 22 Shaping Samford’s Campus Samford religion professor David Bains discusses the shaping of Samford’s campus from the 1940s on, including an early version planned by descendants of Frederick Olmstead, designer of New York City’s Central Park and the famed Biltmore House and Gardens in North Carolina. 29 The Samford Pharmacist Pharmacy Dean Joseph O. Dean reflects on learning and teaching that touch six decades at Samford in the McWhorter School of Pharmacy newsletter, an insert in this Seasons. Check out the latest news from one of Samford’s oldest component colleges, dating from 1927. 38 Bird’s Eye View of Baltimore That funny fellow inspiring guffaws and groans as the Baltimore Oriole mascot is none other than former “Spike” Mike Milton of Samford. He made almost 400 appearances last year for the American League baseball team, including the New York City wedding -

Downloads/Bfi-Film- London: Creative Diversity Education-And-Industry- Network

The Journal of Media and Diversity Issue 01 Winter 2020 Sir Lenny Henry, Leah Cowan, David Olusoga, Marverine Duffy, Charlene White, Kimberly McIntosh, Professor Stuart Hall, Kesewa Hennessy, Will Norman, Emma Butt, Dr David Dunkley Gyimah, Dr Erica Gillingham, Dr Peter Block, Suchandrika Chakrabarti 1 REPRESENTOLOGY THE JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND DIVERSITY REPRESENTOLOGY The Journal of Media and Diversity Editorial Mission Statement Welcome to Representology, a journal dedicated to research and best-practice perspectives on how to make the media more representative of all sections of society. A starting point for effective representation are the “protected characteristics” defined by the Equality Act 2010 including, but not limited to, race, gender, sexuality, and disability, as well as their intersections. We recognise that definitions of diversity and representation are dynamic and constantly evolving and our content will aim to reflect this. Representology is a forum where academic researchers and media industry professionals can come together to pool expertise and experience. We seek to create a better understanding of the current barriers to media participation as well as examine and promote the most effective ways to overcome such barriers. We hope the journal will influence policy and practice in the media industry through a rigorous, evidence-based approach. Our belief is that a more representative media workforce will enrich and improve media output, enabling media organisations to better serve their audiences, and encourage a more pluralistic and inclusive public discourse. This is vital for a healthy society and well-functioning democracy. We look forward to working with everyone who shares this vision. 2 ISSUE 01 WINTER 2020 CONTENTS EDITORIAL 04 Lessons from history In the wake of Black Lives Matter, many Sir Lenny Henry and David Olusoga people at the helm of the UK media industry interview. -

Delegates Brochure 2020

©ALTTitle Animation Address DM Ltd ‘Monty & Co’ © 2019 Pipkins Productions Limited The Snail and the Whale ©Magic Light Pictures Ltd 2019 Bigmouth Elba Ltd Clangers: © 2019 Coolabi Productions Limited, Smallfilms Limited and Peter Firmin © Tiger Aspect Productions Limited 2019 UK@Kidscreen delegation organised by: 2020 Tuesday 7 July 2020, Sheffield UK The CMC International Exchange is the place to meet UK creatives, producers and service providers. • Broadcasters, co-producers, funders and investors from across the world are welcome to this focused market day. • Meetings take place in one venue on one day (7 July 2020). • Writers, IP developers, producers of TV and digital content, service providers, UK kids’ platforms and distributors are all available to take meetings. • Bespoke Meeting Mojo system is used to upload profiles in advance, present project information and request meetings. • Discover innovative, fresh content, build new partnerships and access the best services and expertise. • Attend the world’s largest conference on kids’ and youth content, 7-9 July 2020 in Sheffield www.thechildrensmediaconference.com • For attendance, please contact [email protected] UK@Kidscreen 2020 3 ContentsTitle Forewords 4-5 Kelebeck Media Nicolette Brent KidsCave Studios Sarah Baynes Kids Industries UK Delegate Companies 6-52 Kids Insights 3Megos KidsKnowBest Acamar Films King Banana TV ALT Animation Lightning Sprite Media Anderson Entertainment LoveLove Films Beyond Kids Bigmouth Audio Lupus Films Cloth Cat Animation Magic Light -

Preserving the Lost Cause Through “Dixie's Football

PRESERVING THE LOST CAUSE THROUGH “DIXIE’S FOOTBALL PRIDE”: THE BIRMINGHAM NEWS’ COVERAGE OF THE ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE DURING THE CORE OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, 1961 – 1966 ________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ By ERIC W. STEAGALL Dr. Earnest Perry, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2016 © Copyright by Eric W. Steagall 2016 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled PRESERVING THE LOST CAUSE THROUGH “DIXIE’S FOOTBALL PRIDE”: THE BIRMINGHAM NEWS’ COVERAGE OF THE ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE DURING THE CORE OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, 1961 – 1966 presented by Eric W. Steagall, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ______________________________________________ Associate Professor Earnest L. Perry ___________________________________________ Associate Professor Berkley Hudson _______________________________________ Associate Professor Greg Bowers _________________________________ Professor John L. Bullion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research unofficially began in 2014 after I finished watching, “Ghosts of Ole Miss,” an ESPN Films 30 for 30 documentary inspired and narrated by Wright Thompson (B.J. ‘01). This was the beginning of my fascination with southern history, thanks to Wright’s unique angle that connected college football to the Civil War’s centennial. As I turned off Netflix that night, I remember asking myself two questions: 1) Why couldn’t every subject in school be taught using sports; and 2) Why do some people choose to ignore history while others choose not to forget it? The latter question seemed to provide more answers, so I began privately studying the Civil War for about a year. -

Escape Velocity: Growing Salford's Digital and Creative Economy

December 2017 ESCAPE VELOCITY: Growing Salford’s Digital & Creative Economy Max Wind-Cowie RESPUBLICA RECOMMENDS Acknowlegements As part of the research for this report, ResPublica interviewed a wide range of third party, industry and Governmental stakeholders with relevant expertise in the digital, media and creative industries. The report recommendations have benefited from the collective insight of many of our interviewees. However, the content and views contained in this report are those of ResPublica and do not necessarily reflect the policy positions of wider stakeholders. We would like to thank the author of this report, Max Wind-Cowie, for providing the original content before his secondment to the National Infrastructure Commission in August 2017. Special thanks to Justin Bentham, Strategic Economic Growth Manager, Salford City Council for his research and analysis. We would also like to thank Mark Morrin, Principle Research Consultant, ResPublica, for his contributions to final drafting and editing. About ResPublica The ResPublica Trust (ResPublica) is an independent non-partisan think tank. Through our research, policy innovation and programmes, we seek to establish a new economic, social and cultural settlement. In order to heal the long-term rifts in our country, we aim to combat the concentration of wealth and power by distributing ownership and agency to all, and by re-instilling culture and virtue across our economy and society. Escape Velocity Contents Foreword 2 1. Introduction 5 2. The Salford Story 9 Anchor institutions and economic clusters 11 The BBC as a key anchor institution 14 Beyond the BBC 17 Beyond broadcast 19 Beyond MediaCityUK 20 A cluster with real impact 22 Achieving escape velocity 23 3. -

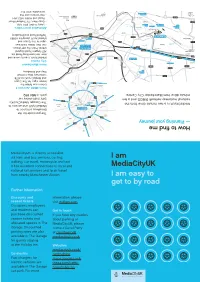

I Am Mediacityuk I Am Easy to Get to by Road

car park. For more more For park. car news/index.jsp available in The Garage Garage The in available theaa.com/traffic- electric vehicles are are vehicles electric maps.google.co.uk Fast chargers for for chargers Fast gettinghere Go electric Go mediacityuk.co.uk/ Websites at the Holiday Inn. Holiday the at for guests staying staying guests for . mediacityuk.co.uk available in The Garage Garage The in available david.parry@ at parking rates are also also are rates parking contact David Parry Parry David contact Garage. Discounted Discounted Garage. MediaCityUK, please please MediaCityUK, allocated spaces in The The in spaces allocated about parking at at parking about season tickets and and tickets season If you have any queries queries any have you If purchase discounted discounted purchase Get in touch in Get and residents can can residents and Occupiers, employees employees Occupiers, . ev.tfgm.com visit season tickets season information, please please information, Discounts and and Discounts Further Information Further get to by road by to get I am easy to to easy am I from nearby Manchester Airport. Manchester nearby from national rail services and to air travel travel air to and services rail national It has excellent connections to local and and local to connections excellent has It MediaCityUK walking, car travel, motorcycle and taxi. taxi. and motorcycle travel, car walking, I am am I via tram and bus services, cycling, cycling, services, bus and tram via MediaCityUK is directly accessible accessible directly is MediaCityUK How to find me Bury M66 Leeds and M1 — Planning your journey M62 J18 Oldham M61 M60 Preston and M6 J15 The postcode for the Salford Manchester Broadway entrance to J12 M602 Sheffield MediaCityUK and access to MediaCityUK is a two minute drive from the MediaCityUK M62 J24 The Garage, MediaCityUK’s national motorway network (M602) and a ten Trafford M67 M60 M60 24hr multi-storey car Liverpool Warrington minute drive from Manchester City Centre. -

Second and Third Generation South Asian Service Sector Entrepreneurship in Birmingham, United Kingdom

SECOND AND THIRD GENERATION SOUTH ASIAN SERVICE SECTOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN BIRMINGHAM, UNITED KINGDOM BY SUNITA DEWITT A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences University of Birmingham May 2011 I University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores second and third generation South Asian entrepreneurship in Britain. To date the majority of studies have focused on understanding entrepreneurship by first generation South Asian immigrants who established businesses in traditional sectors of the economy, frequently as a result of „push‟ and „pull‟ factors. This thesis extends the work on South Asian entrepreneurship to second and third generation South Asian entrepreneurs. These generations are detached from immigrant status and the majority have been assimilated into British culture and economy, they are the British/Asians. This thesis explores the driving forces and strategies deployed by these succeeding generation of South Asians in setting up businesses in Birmingham‟s service sector economy. A framework is developed to understand South Asian entrepreneurship that consists of four elements: individual‟s driving forces, financial input, support networks and market opportunities. -

University Communications Five-Year Report Ending 2011

June 30, 2011 Educational Support and Administrative Review University Communications Five-year Report ending 2011 Mr. Josh Woods Director 1 | P a g e 1. Overview of Department 1.1 Brief overview of department/area The Office of University Communications serves the University of North Alabama community by providing public relations, marketing and advertising services. The six-person staff operates as an in-house ad agency, providing communication strategies and media relations supported by professionally written, photographed and designed print and online pieces. 1.2 Mission statement for the department/area The mission of the Office of University Communications is to communicate UNA’s history – past, present and future – by providing a coherent, cohesive positive image of the university through marketing and media relations. 1.3 Goals and objectives of the department/area Since October 2008, many of the goals and objectives for the Office of University Communications have centered on building a new program. Prior to that time, the university had no central office for all university marketing and advertising. Instead, it operated an Office of University Relations, which was strictly a media relations office, and an Office of Publications, which handled university publications of all kinds, from business cards and letterhead to the student newspaper. Major goals since then have included: The creation of one team from two offices that previously had operated under two different directors and had collaborated on few, if any, projects The -

2007 Alabama Soccer Media Guide

01699f_Text.qxp 8/29/07 9:01 AM Page 1 THIS IS ALABAMA SOCCER Contents 2007 ALABAMA SOCCER MEDIA GUIDE This is Alabama Soccer Quick Facts . .2 Media Information . .3 The University of Alabama . .5 President Dr. Robert E. Witt . .6 Athletic Director Mal Moore . .7 Athletic Support Staff . .8-9 Center for Athletic Student Services . .10 Commitment to Excellence . .11 Alabama Community Service Leaders . .12-13 2007 Outlook . .14-15 All- Time Jersey Numbers . .16 Breaking Down the 2007 Team . .17 The Team Head Coach Don Staley . .18-19 Assistant Coach Nikki Smith . .20 Assistant Coach Jeremy Hampton . .21 The Players . .23-47 Soccer Support Staff . .48 The Opponents Non Confrence Opponents . .49-54 SEC Opponents . .55 2006 in Review 2006 Statistics . .62 2006 Lineups and Boxscores . .64 Southeastern Confrence SEC Soccer “Setting the Standard” . .66 The History Individual Records . .68 Team Records . .69 UA Soccer Stadium Records . .72 All-Time vs. All Opponents . .73 All-Time Results . .75 All-Time Roster . .79 ALABAMASOCCER2007 1 01699f_Text.qxp 8/29/07 9:01 AM Page 2 THIS IS ALABAMA SOCCER 2007 Alabama Soccer 2007 2006 Record: 5-14 2006 SEC Record/Finish: 1-9 / 5th SEC West All-Time Record: 148-137-12 (16) Returning Letterwinners (14) Quick # Name Class EXP HT POS Hometown/Previous School 3 Susie Beard SR 2VL 5’4 M/F Bowling Green, Ky./Bowling Green 18 Alex Butera SO 1VL 5’7 F Orlando, Fla./Bishop Moore Facts 14 Kailey Corken SO 1VL 5’7 M Cincinnati, Ohio/ Turpin 23 Jessica Deegan JR 2VL 5’8 F/M Centreville, Va./ Westfield 00 Kara Gudmens JR 2VL 5’9 GK Cincinnati, Ohio/ Milford UNIVERSITY INFORMATION 25 Kelsey King SO 1VL 5’8 F Kingwood, Texas/Kingwood Location:Tuscaloosa, Alabama 24 Cara Kelly JR 2VL 5’3 M Cincinnati, Ohio/ St. -

Downloading Vouchers/Codes for Games and Getting Tickets for Gigs/Music Releases Earlier and Cheaper

Social Media, Television And Children Project Report 1 STAC Table of contents SECTION 1: BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY 2 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Aims, Objectives and Research Questions 3 1.3 Methodology 3 1.4 Approaches to Data Analysis 6 SECTION 2: MAIN FINDINGS 7 2.1 Social Media, Television and Children: Survey Data Analysis 8 2.2 Social Media, Television and Children: Qualitative Data Analysis 31 SECTION 3: CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 3.1 Summary of Key Findings 58 3.2 Implications of the Study for Research 60 3.3 Concluding Remarks 61 REFERENCES 62 APPENDICES 63 Appendix 1: Survey Questions 63 Appendix 2: Schedule for Use with Case Study Families 96 Appendix 3: Interview Schedule for Use with Focus Groups 100 Appendix 4: Interview Schedule for Telephone Interviews 103 Appendix 5: Statistical Analysis of Survey Data 106 To cite this report: Marsh, J., Law, L., Lahmar, J., Yamada-Rice, D, Parry, B., Scott, F., Robinson, P., Nutbrown, B., Scholey, E., Baldi, P., McKeown, K., Swanson, A., Bardill, R. (2019) Social Media, Television and Children. Sheffield: University of Sheffield. Social Media, Television And Children 2 Section 1 Background To The Study 3 STAC 1.1 Introduction This report outlines the key findings of a co-produced study, developed in collaboration between academics from the University of Sheffield’s School of Education, BBC Children’s and Dubit. The project was co-produced in that all project partners contributed to the development of the project aims and objectives and were involved in data collection, analysis and dissemination. The aim of the study was to identify children and young people’s (aged from birth to 16) use of social media and television. -

Pageflex Server

Media and Communication - BA (Hons) Web and New Media This course is designed for students who want to develop a career in web design or management. COURSE FACTS Faculty Birmingham School of Media Apply through UCAS Application Institution Code B25 / Course Code G493 Location City North Campus Duration Full Time: 3 Years WHY CHOOSE US? • Chance to study at a Skillset Media Academy - one of only 23 academies across the UK chosen to help develop a new wave of media talent. • Rated 12th for Media in the Guardian University Guide for 2012 • Placements play a crucial role (industry placements - equivalent to 70 hours in your first year and 105 hours in your second - are compulsory); recent students have gained invaluable experience at BSkyB, the BBC, Maverick Television and Endemol. • Encourages you to be a ‘thinking media worker’ - an individual, not just a cog in a machine; offers a balance of media production skills and academic study of the industry. ENTRY REQUIREMENTS Students must have at least one of the following: • BBC at A Level,Subject excluding General Studies and to Critical Thinking approval by • BTEC National Diploma overall grade DMM. • International Baccalaureate Creativewith 28 points. Services • Access course - pass overall including merit in 18 credits at level 3 • Equivalent qualifications or experience. FEES AND FUNDING (2012/13) Full Time UK/EU students: £8,200 For further information about our 2012 fees and funding options, see our FAQ section at www.bcu.ac.uk/fees2012faqs COURSE DETAILS COURSE OVERVIEW This course is designed for students who want to develop a career in web design or management, or any of the fast-growing areas of new media production, including the gaming industry, mobile phones, and interactivity.