Rembrandt's Paint Author(S): Benjamin Binstock Source: RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Frick Collection, New York Works from the Permanent Collection

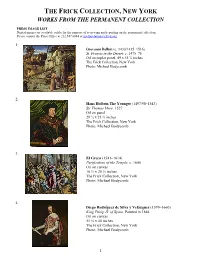

THE FRICK COLLECTION, NEW YORK WORKS FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available solely for the purpose of reviewing and reporting on the permanent collection. Please contact the Press Office at 212.547.6844 or [email protected]. 1. Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430/1435–1516) St. Francis in the Desert, c. 1475–78 Oil on poplar panel, 49 x 55 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2. Hans Holbein The Younger (1497/98–1543) Sir Thomas More, 1527 Oil on panel 29 ½ x 23 ¾ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3. El Greco (1541–1614) Purification of the Temple, c. 1600 Oil on canvas 16 ½ x 20 ⅝ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 4. Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660) King Philip IV of Spain, Painted in 1644 Oil on canvas 51 ⅛ x 40 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 1 5. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) Officer and Laughing Girl, c. 1657 Oil on canvas 19 ⅞ x 18 ⅛ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 6. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) Self-Portrait, dated 1658 Oil on canvas 52 ⅝ x 40 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 7. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) The Rehearsal, 1878–79 Oil on canvas 18 ¾ x 24 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 8. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) The Meeting (one panel in the series called The Progress of Love), 1771–73 Oil on canvas 125 x 96 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2 9. -

Openeclanewfieldinthehis- Work,Ret

-t horizonte Beitràge zu Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft horizons Essais sur I'art et sur son histoire orizzonti Saggi sull'arte e sulla storia dell'arte horizons Essays on Art and Art Research Hatje Cantz 50 Jahre Schweizerisches lnstitut flir Kunstwissenschaft 50 ans lnstitut suisse pour l'étude de I'art 50 anni lstituto svizzero di studi d'arte 50 Years Swiss lnstitute for Art Research Gary Schwartz The Clones Make the Master: Rembrandt in 1ó50 A high point brought low The year r65o was long considerecl a high point ot w-atershed fcrr Rem- a painr- orandt ls a painter. a date of qrear significance in his carecr' Of ng dated ,65o, n French auction catalogue of 18o6 writes: 'sa date prouve qu'il était dans sa plus grande force'" For John Smith, the com- pl.. of ih. firr, catalogue of the artistt paintings in r836, 165o was the golden age.' This convictíon surl ived well into zenith of Rembranclt's (It :]re tnentieth centufy. Ifl 1942, Tancred Borenius wfote: was about r65o one me-v sa)i that the characteristics of Rembrandt's final manner Rosenberg in r.rr e become cleady pronounced.'l 'This date,'wroteJakob cat. Paris, ro-rr r8o6 (l'ugt 'Rembrandt: life and wotk' (r9+8/ ry64),the standard texl on the master 1 Sale June t)).n\t.1o. Fr,,m thq sxns'6rjp1 rrl years, 'can be called the end of his middle period, or equallv Jt :,r many the entrv on thc painting i n the Corpns of this ''e11, the beginning of his late one.'a Bob Haak, in 1984, enriched Renbrandt paintings, r'ith thanks to the that of Rcmbrandt Research Project for show-ing ,r.rqe b1, contrasting Rembrandt's work aftet mid-centurl' with to me this and other sections of the draft 'Rembrandt not only kept his distance from the new -. -

煉金術:論象徵概念與創作意識之源 Alchemy: a Study of the Symbols’ Conceptions and Creative Consciousness

國立臺灣師範大學美術研究所繪畫創作理論組 博士論文 指導教授:陳淑華 博士 論文題目: 煉金術:論象徵概念與創作意識之源 Alchemy: A Study of the Symbols’ Conceptions and Creative Consciousness 研究生:張欽賢 撰 2013/03/20 1 煉金術:論象徵概念與創作意識之源 中文摘要 煉金術是註記人類探索自我意識與物質世界的廣袤史觀。它是宗教神 話思想,以及個人洞察自身認知根源的集合體。煉金術統合物質形式的象 徵意識以及精神心靈的昇華幻化,並將之轉變成思想與技藝之間的關鍵聯 繫。藝術家藉此以助於學習外在與內在、題材與創作活性的整合,使繪畫 與其它視覺藝術如同煉金術一般,成為聯接物質與心理世界的範例。回顧 典籍所載,古人所言之藝術與藝術家,亦與煉金術士一般,充滿了神秘難 解之奇幻異數,而非今日所使用詞彙之實質意含。 本篇研究要旨在於探索煉金術思想脈絡以及其象徵系統,各篇皆以傳 統象徵系統引導創作之源,論述象徵體系之中,煉金術為之詮釋作為創造 者的終極創生,指引創作者所需之超越智慧的自然共感,與追尋超越物質 與精神世界的開放思想,以及深刻的創作情緒。本篇論文亦以此尋思古代 習藝者以及現代心理與美學理論,研究存於內心的信仰與創作程序以何種 圖面形式再現虛無的想像。以象徵系統,作為探究抽象概念轉化為繪畫創 作因素之工具與潛意識攫取想像的能力。 關鍵詞:煉金術,四元素,哲人石,曼陀羅,象徵心理,異教藝術。 i Alchemy: A Study of the Symbols’ Conceptions and Origin Consciousness of Creation Abstract Alchemy is the history of humanity’s self-awareness and marvel with the physical world. It is collective and individual research for perspicacity and the origins of religion, mythology, and personal self-identity. Alchemy is at once a symbolic consciousness of substantial forms and a symbolic utterance of the spiritual and psychological transformations of the spirit, became a connection between wisdom and art. The artist has been given the possibility of integrating his outward and inward creation, his subject matter and his creative activity. Painting and other visual arts are one intent example of communication between physical and psychological world, and other is alchemy. If we look back at the whole art history existence, the appearance of art and artist, just like alchemist, seems a curious phenomenon indeed, an ethereal secret that cannot easily be explained in terms of contemporary lexicon that we may real understand. While the thrust of this study is directed at elucidating the history of alchemy and system of symbols, every chapter includes explicable the form of symbols from the origin of traditions. -

ICLIP & MAIL Tornadoes Rip Path of Death

PAGE SIXTEEN - EVENING HERALD. Tues.. April 10, 1978 Frank and Emaat EDUCATIONAL TV DINNERS T H f t Y ' P E *'epueArioN AL" i B c n u s B Police Malting Plans Panel Passes Measure Residents Not in Tune Caldwell Stops RSox, r- 1 IF y o u BAT O N E, For the Energy Crisis To Create Gaming Czar To Song of the Rails Jackson Sparks Yanks Page 3 Page 10 Y o u 'L l S e Page 12 Page 13 N B x r t i m b . Strv/CM O lltr td 31 S » n lc 0M OUtrad 31 Painting-Papering 32 Building Contracting 33 E X P E R T PAIN T IN G and INCOME TAX .) P. LEWIS & SON- Interior LEON CIESZYNSKI LANDSCAPING Specializlnf; and Exterior painting, paper BUILDER- New Homes. Ad THW/ti 4-10 Haudipfitpr PREPARATION in Exterior House Painting. hanging, rcmcxieling. carpen ditions. Remodeling. Rec Tree pruning, spraying, try. Fully insured 649-9658. Rooms. 'Garages, FHtchenq Fair Tonight, mowing, wcemng. Call 742- Remodeled. Ceilings. Bath Dogs-BIrdt-Pelt 43 Apaifmentt For Bant 53 Wanted to Bent 57 Autos For Sale 61 ftliSINESS A INDIVIDUAL 7947. ' PERSONAL Paperhanging Tile. Dormers, Roofing Sunny Thursday INCOiME TAXES For particular people, by Residential or Commercim, COCKER SPANIEL THREE BEDROOM USED GAR SPECULS Dick. Call 643-5703 anytime, 649-4291. PUPPIES - AKC Registered. DUPLEX- Stove, I’HEPAHKD - In the com- 1975 nyMOUTH D U tm Details on page 2 Inrl of your home or office, Have shots. Great Easter refrigerator, dishwasher. I'/z TEACHERS- Experienced baths. -

The Leiden Collection

Slaughtered Pig ca. 1660–62 Attributed to Caspar Netscher oil on panel 36.7 x 30 cm CN-104 © 2017 The Leiden Collection Slaughtered Pig Page 2 of 8 How To Cite Wieseman, Marjorie E. "Slaughtered Pig." In The Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2017 The Leiden Collection Slaughtered Pig Page 3 of 8 Seventeenth-century Netherlandish images of slaughtered oxen and pigs Comparative Figures have their roots in medieval depictions of the labors of the months, specifically November, the peak slaughtering season. The theme was given new life in the mid-sixteenth century through the works of the Flemish painters Pieter Aertsen (1508–75) and Joachim Beuckelaer (ca. 1533–ca. 1574), who incorporated slaughtered and disemboweled animals in their vivid renderings of abundantly supplied market stalls, and also explored the theme as an independent motif.[1] The earliest instances of the motif in the Northern Netherlands come only in the seventeenth century, possibly introduced by immigrants from the south. During the early 1640s, the theme of the slaughtered animal—split, splayed, and Fig 1. Barent Fabritius, suspended from the rungs of a wooden ladder—was taken up by (among Slaughtered Pig, 1665, oil on others) Adriaen (1610–85) and Isack (1621–49) van Ostade, who typically canvas, 101 x 79.5 cm, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, situated the event in the dark and cavernous interior of a barn, stable, or Rotterdam, inv. -

Alex Katz Coca Cola Press Release

Alex Katz Coca-Cola Girls 2 November – 21 December, 2018 Timothy Taylor, London, is pleased to present Coca-Cola Girls, an exhibition of new large-scale paintings by Alex Katz inspired by the eponymous, and iconic, figures from advertising art history. The Coca-Cola Girls were an integral component of the company’s advertising from the 1890’s through to the 1960’s, emanating an ideal of the American woman. Initially, the Coca-Cola Girls were reserved and demure, evolving during WWI, and through the era of the pin-up, to images of empowered service women in uniform, and athletic, care-free, women at leisure. In the context of pre-televised advertising, the wall decals and large-scale billboards depicting these figures made a significant impact on the visual language of the American urban landscape. For Katz, this optimistic figure also encapsulates a valuable notion of nostalgia; “That’s Coca-Cola red, from the company’s outdoor signs in the fifties… you know, the blond girl in the red convertible, laughing with unlimited happiness. It’s a romance image, and for me it has to do with Rembrandt’s ‘The Polish Rider.’ I could never understand that painting but my mother and Frank O’Hara both flipped over it, so I realized I was missing something. They saw it as a romantic figure, riding from the Black Sea to the Baltic.” 1 . The poses captured in these new paintings disclose a sense of balletic movement; a left arm extending upwards, a head twisted to the right, a leg poised on the ball of a foot, or a hand extending to and from nowhere - always glimpsed in a fleeting gesture within a dynamic sequence. -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

Ontdek Schilder, Tekenaar, Prentkunstenaar Willem Drost

24317 5 afbeeldingen Willem Drost man / Noord-Nederlands schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, etser Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Drost, Cornelis Drost, Geraerd Droste, Willem van Drost, Willem Jansz. Drost, Guglielmo Drost, Wilhelm signed in Italy: 'G. Drost' (G. for Guglielmo). Because of this signature, he was formerly wrongly also called Cornelis or Geraerd Drost. In the past his biography was partly mixed up with that of the Dordrecht painter Jacob van Dorsten. Kwalificaties schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, etser Nationaliteit/school Noord-Nederlands Geboren Amsterdam 1633-04/1633-04-19 baptized on 19 April 1633 in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam (Dudok van Heel 1992) Overleden Venetië 1659-02/1659-02-25 buried on 25 February 1659 in the parish of S. Silvestro (Bikker 2001 and Bikker 2002). He had been ill for four months when he dued of fever and pneumonia. Familierelaties in dit veld wordt een familierelatie met één of meer andere kunstenaars vermeld. son of Jan Barentsen (1587-1639) and Maritje Claesdr. (1591-1656). His brother Claes Jansz. Drost (1621-1689) was an ebony worker. Zie ook in dit veld vindt u verwijzingen naar een groepsnaam of naar de kunstenaars die deel uitma(a)k(t)en van de groep. Ook kunt u verwijzingen naar andere kunstenaars aantreffen als het gaat om samenwerking zonder dat er sprake is van een groep(snaam). Dit is bijvoorbeeld het geval bij kunstenaars die gedeelten in werken van een andere kunstenaar voor hun rekening hebben genomen (zoals bij P.P. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt

Originalveröffentlichung in: Artibus et Historiae 21 (2000), Nr. 41, S. 197-205 ZDZISLAW ZYGULSKI, JR. Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt Few paintings included among outstanding creations of chaser was an outstanding American collector, Henry Clay modern painting provoke as many disputes, polemics and Frick, king of coke and steel who resided in Pittsburgh and passionate discussions as Rembrandt's famous Lisowczyk, since 1920 in New York where, in a specially designed build 1 3 which is known abroad as the Polish Rider . The painting was ing, he opened an amazingly beautiful gallery . The transac purchased by Michat Kazimierz Ogihski, the grand hetman of tion, which arouse public indignation in Poland, was carried Lithuania in the Netherlands in 1791 and given to King out through Roger Fry, a writer, painter and art critic who occa Stanislaus Augustus in exchange for a collection of 420 sionally acted as a buyer of pictures. The price including his 2 guldens' worth of orange trees . It was added to the royal col commission amounted to 60,000 English pounds, that was lection in the Lazienki Palace and listed in the inventory in a little above 300,000 dollars, but not half a million as was 1793 as a "Cosaque a cheval" with the dimensions 44 x 54 rumoured in Poland later. inch i.e. 109,1 x 133,9 cm and price 180 ducats. In his letter to the King, Hetman Ogihski called the rider, The subsequent history of the painting is well known. In presented in the painting "a Cossack on horseback". -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Rembrandt Remembers – 80 Years of Small Town Life

Rembrandt School Song Purple and white, we’re fighting for you, We’ll fight for all things that you can do, Basketball, baseball, any old game, We’ll stand beside you just the same, And when our colors go by We’ll shout for you, Rembrandt High And we'll stand and cheer and shout We’re loyal to Rembrandt High, Rah! Rah! Rah! School colors: Purple and White Nickname: Raiders and Raiderettes Rembrandt Remembers: 80 Years of Small-Town Life Compiled and Edited by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins Des Moines, Iowa and Harrisonburg, Virginia Copyright © 2002 by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins All rights reserved. iii Table of Contents I. Introduction . v Notes on Editing . vi Acknowledgements . vi II. Graduates 1920s: Clifford Green (p. 1), Hilda Hegna Odor (p. 2), Catherine Grigsby Kestel (p. 4), Genevieve Rystad Boese (p. 5), Waldo Pingel (p. 6) 1930s: Orva Kaasa Goodman (p. 8), Alvin Mosbo (p. 9), Marjorie Whitaker Pritchard (p. 11), Nancy Bork Lind (p. 12), Rosella Kidman Avansino (p. 13), Clayton Olson (p. 14), Agnes Rystad Enderson (p. 16), Alice Haroldson Halverson (p. 16), Evelyn Junkermeier Benna (p. 18), Edith Grodahl Bates (p. 24), Agnes Lerud Peteler (p. 26), Arlene Burwell Cannoy (p. 28 ), Catherine Pingel Sokol (p. 29), Loren Green (p. 30), Phyllis Johnson Gring (p. 34), Ken Hadenfeldt (p. 35), Lloyd Pressel (p. 38), Harry Edwall (p. 40), Lois Ann Johnson Mathison (p. 42), Marv Erichsen (p. 43), Ruth Hill Shankel (p. 45), Wes Wallace (p. 46) 1940s: Clement Kevane (p. 48), Delores Lady Risvold (p.