Tax Controversies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment of President Donald John Trump The

1 116TH CONGRESS " ! DOCUMENT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 116–95 IMPEACHMENT OF PRESIDENT DONALD JOHN TRUMP THE EVIDENTIARY RECORD PURSUANT TO H. RES. 798 VOLUME XI, PART 7 Historic Materials Printed at the direction of Cheryl L. Johnson, Clerk of the House of Representatives, pursuant to H. Res. 798, 116th Cong., 2nd Sess. (2020) JANUARY 23, 2020.—Ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 39–530 WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Sep 11 2014 23:15 Jan 24, 2020 Jkt 039530 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 E:\HR\OC\HD095P29.XXX HD095P29 lotter on DSKBCFDHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JERROLD NADLER, New York, Chairman ZOE LOFGREN, California DOUG COLLINS, Georgia, Ranking Member SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., STEVE COHEN, Tennessee Wisconsin HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas KAREN BASS, California JIM JORDAN, Ohio CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana KEN BUCK, Colorado HAKEEM S. JEFFRIES, New York JOHN RATCLIFFE, Texas DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island MARTHA ROBY, Alabama ERIC SWALWELL, California MATT GAETZ, Florida TED LIEU, California MIKE JOHNSON, Louisiana JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland ANDY BIGGS, Arizona PRAMILA JAYAPAL, Washington TOM MCCLINTOCK, California VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida DEBBIE LESKO, Arizona J. LUIS CORREA, California GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania MARY GAY SCANLON, Pennsylvania, BEN CLINE, Virginia Vice-Chair KELLY ARMSTRONG, North Dakota SYLVIA R. GARCIA, Texas W. GREGORY STEUBE, -

Democracy and the NATO Alliance: Upholding Our Shared Democratic Values”

Prepared Statement for the Record “Democracy and the NATO Alliance: Upholding our Shared Democratic Values” Susan Corke Senior Fellow, German Marshall Fund and Director of Transatlantic Democracy Working Group House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment U.S. House of Representatives November 13, 2019 Chairman Keating, Ranking Member Kinzinger, Distinguished Members of this Committee, thank you for holding this hearing and inviting me to testify before you on an issue that I believe is fundamental to American security and to our role as a leader of the democratic community of nations. It is a particular honor to be here today because Representatives Keating and Kinzinger have been two of the most principled voices in calling for a reinvigoration of democracy and the NATO Alliance as we contend with an era of authoritarian resurgence. On May 8th they both spoke powerfully at an event hosted by German Marshall Fund and the Transatlantic Democracy Working Group on the need to continue fighting for freedom and the ideals we value most, emphasizing this is in America’s interest. Representative Keating asked a pointed question this event, “What do we have that Russia and China don’t have? A coalition, NATO, that has resulted in 70 years of prosperity and peace.” This year is NATO’s 75th birthday and the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall; these anniversaries could have marked the success of the transatlantic project and the triumph of democracy. Instead, it is clear that after seven decades as the world’s preeminent military alliance, NATO’s future is in danger, facing urgent challenges that require immediate attention, including a recommitment to democratic values as a foundation of our security. -

519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190

DEMOCRACY-2018/09/17 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION WILL DEMOCRACY WIN? THE RECURRING BATTLE BETWEEN LIBERALISM AND ITS ADVERSARIES Washington, D.C. Monday, September 17, 2018 Opening Remarks JOHN R. ALLEN President, The Brookings Institution Panel 1 STEVE INSKEEP, Moderator Host, “Morning Edition,” NPR NORMAN EISEN Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution ROBERT KAGAN Stephen & Barbara Friedman Senior Fellow, Project on International Order and Strategy The Brookings Institution Remarks WILLIAM A. GALSTON Ezra K. Zilkha Chair and Senior Fellow, Governance Studies The Brookings Institution Panel 2 LINDA WERTHEIMER, Moderator Senior National Correspondent, NPR CHARLES BLACK, JR. President, Pentad Plus LLC NORMAN EISEN Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution MARC ROBINSON Professor of English and Theater Studies, Yale University LAURENE SHERLOCK Owner, Greystone Appraisals LLC ALEXANDER TOUSSAINT Deacon * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 500 Montgomery Street, Suite 400 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 DEMOCRACY-2018/09/17 2 P R O C E E D I N G S GENERAL ALLEN: Ladies and gentlemen, good morning. Welcome to Brookings. I'm John Allen; I'm the president of the Institution. You are most welcome today, and for those coming in by webcast, we welcome you as well. Today we're going to be discussing something concerning many of us at this moment in history. It's the growing tide of illiberalism, as it seems to be threatening increasingly democratic institutions and governments on both sides of the Atlantic. I think it's fair to say that we've learned that democracy is not inevitable and it needs to be understood, it needs to be nurtured, it needs to be cared for, and it needs to be guarded with great vigilance. -

Link to PDF Version

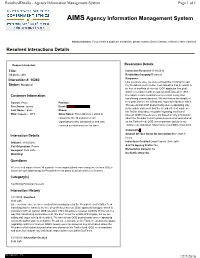

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, DECEMBER 12, 2011 No. 190 Senate The Senate met at 2 p.m., and was the State of Delaware, to perform the vacancies because Republicans were in called to order by the Honorable CHRIS- duties of the Chair. the majority in that court. So they TOPHER A. COONS, a Senator from the DANIEL K. INOUYE, wanted to defeat this competent State of Delaware. President pro tempore. woman, and that is what they did with Mr. COONS thereupon assumed the these vacancies still there in that PRAYER chair as Acting President pro tempore. court. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- f They blocked the nomination of fered the following prayer: Richard Cordray to lead the Consumer RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY Let us pray. Financial Protection Bureau, despite LEADER God, our King, You are clothed in his obviously deep qualifications for majesty and strength. Your throne has The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- the job. He has a long history of pro- been established from the beginning pore. The majority leader is recog- tecting the middle class against unfair and You existed before time began. nized. practices by financial predators and he Help our lawmakers today to do their f would have been a great asset in our fight to protect Main Street from the work, striving to labor for Your glory. SCHEDULE Give them the purity of life and hon- kind of Wall Street greed that caused esty of purpose to walk in Your way. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2017 No. 18 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Victims were people from all types of And let me make it clear once again: called to order by the Speaker pro tem- backgrounds. Mr. Speaker, they all had This is not taxpayer funded money. pore (Mr. BOST). something in common. They were a si- Criminals paid for this. Criminals are f lent group of people who were preyed paying the rent on the courthouse and on by criminals. After the crime was they are paying for the system that DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO over, many suffered for years. they have created. TEMPORE Finally, Congress came up with a So what is the problem? The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- novel idea, a law that established the Well, the problem is, Mr. Speaker, fore the House the following commu- Crime Victims Fund to support victims only a fraction of that money is spent nication from the Speaker: of crime. But instead of using taxpayer each year for victims, depriving them WASHINGTON, DC, money for the fund, Congress had a dif- of needed services and that money. February 2, 2017. ferent idea. Why not force the crimi- More money continues to go in the I hereby appoint the Honorable MIKE BOST nals, the traffickers, the abusers, and fund every year because less and less of to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

How Campaign Finance Reform Restructured Campaigns and the Political World

Catholic University Law Review Volume 58 Issue 4 Summer 2009 Article 5 2009 Goodbye Soft Money, Hello Grassroots: How Campaign Finance Reform Restructured Campaigns and the Political World Laura MacCleery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Laura MacCleery, Goodbye Soft Money, Hello Grassroots: How Campaign Finance Reform Restructured Campaigns and the Political World, 58 Cath. U. L. Rev. 965 (2009). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol58/iss4/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOODBYE SOFT MONEY, HELLO GRASSROOTS: HOW CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM RESTRUCTURED CAMPAIGNS AND THE POLITICAL WORLD Laura MacCleery+ I. IN TRO D UCTION ........................................................................................... 966 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF POLITICAL PARTY FUND-RAISING ........................... 971 A. Direct Mail Fund-raisingand the Seeds of a Republican R evolu tion .................................................................................................. 9 7 1 B. The Democrats'Response:Mixing Business with Politics................... 973 C. A Culture of Corruptionand Scandalon the Hill ................................ 975 D. The Rise of Soft Money ........................................................................ -

Presented by Openthegovernment.Org

Presented by OpenTheGovernment.org Friday, March 19 – 12:00 – 2:00 pm Center for American Progress 1333 H Street NW, 10th Floor On his first full day in office, President Obama committed his Administration "to creating an unprecedented level of openness in Government." To help meet that goal, the Administration issued an Open Government Directive and a new Memorandum on Freedom of Information Act and Attorney General Guidelines. The Administration has also launched an expansive effort to open up data to developers, advocates, and the public via Data.gov. During this program, our 5th annual Sunshine Week webcast, leading experts on transparency issues from inside and outside government will discuss if and how these initiatives have made the federal government more open, and what remains to be done. 12:00 Opening Remarks – Reece Rushing, Director of Government Reform, Center for American Progress -- Patrice McDermott, Director, OpenTheGovernment.org 12:05 Panel One: The Open Government Directive – Creating Lasting Government Openness? Norm Eisen, Special Counsel to the President for Ethics and Government Reform; Jim Harper, Director of Information Policy Studies, Cato Institute; John Wonderlich, Policy Director, Sunlight Foundation; and Patrice McDermott, Director, OpenTheGovernment.org (moderator) 12:50 Panel Two: FOIA – New Changes to the Oldest Public Access Law Miriam Nisbet, Director, Office of Government Information Services (OGIS); Melanie Pustay, Director, Department of Justice (DOJ) Office of Information Policy (OIP); Melanie Sloan, Executive Director, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), Kevin Goldberg, American Society of News Editors (ASNE) counsel ; and Patrice McDermott, Director, OpenTheGovernment.org (moderator) 1:35 Panel Three –Data.gov – What can do it for me? Laura Beavers, National KIDS COUNT Coordinator, Annie E. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2017 No. 18 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Victims were people from all types of And let me make it clear once again: called to order by the Speaker pro tem- backgrounds. Mr. Speaker, they all had This is not taxpayer funded money. pore (Mr. BOST). something in common. They were a si- Criminals paid for this. Criminals are f lent group of people who were preyed paying the rent on the courthouse and on by criminals. After the crime was they are paying for the system that DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO over, many suffered for years. they have created. TEMPORE Finally, Congress came up with a So what is the problem? The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- novel idea, a law that established the Well, the problem is, Mr. Speaker, fore the House the following commu- Crime Victims Fund to support victims only a fraction of that money is spent nication from the Speaker: of crime. But instead of using taxpayer each year for victims, depriving them WASHINGTON, DC, money for the fund, Congress had a dif- of needed services and that money. February 2, 2017. ferent idea. Why not force the crimi- More money continues to go in the I hereby appoint the Honorable MIKE BOST nals, the traffickers, the abusers, and fund every year because less and less of to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

Download the Report

HUMANITY IN ACTION ACTIVITY REPORT 2019-2020 1 OUR MISSION Humanity in Action is a transatlantic non-profit organization that supports liberal democracy, pluralism and human rights through unique educational programs for college and university students, recent graduates and young professionals with additional programs for high school students and teachers. We educate tomorrow’s leaders on past and present human rights challenges through critical historical as well as contemporary inquiries and cross-cultural dialogue. We connect an ever-growing international community committed to strengthening liberal democracy, human rights and pluralism. We inspire civic engagement to advance social equity, responsibility and justice. Through our work: • We affirm the importance of strengthening democratic values. • We foster environments in which individuals of diverse backgrounds and identities can engage openly and respectfully with contentious and challenging ideas and each other. • We support a vision of pluralistic societies that embrace differences and negotiate their boundaries through constructive political, social and personal dialogue and relationships. • We build a multinational, intergenerational community of emerging and established leaders who share values including justice, equity, anti-racism and anti-discrimination, pluralism and empathy. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Founder . 4 Netherlands . 33 Amsterdam Fellowship . 34 COVID-19 . 8 Action Projects . 35 Additional Programming . 36 The Fellowship . 10 Funders . 39 Bosnia and Herzegovina . 14 Poland . 40 Sarajevo Fellowship . 15 Warsaw Fellowship . 41 Action Projects . 16 Action Projects . 43 Additional Programming . 18 Additional Programming . 44 Funders . 20 Funders . 46 Denmark . 21 United States . 47 Copenhagen Fellowship . 22 John Lewis Fellowship . 48 Action Projects . 23 Detroit Fellowship . 49 Additional Programming . -

Statement Signatories 121418

November 11, 2018 Transatlantic Democracy Working Group Statement on Central European University As members and supporters of the bipartisan Transatlantic Democracy Working Group, we see the refusal of the Hungarian government to enable the prestigious Central European University (CEU) to continue operating its campus in Budapest as a serious blow to academic freedom in Hungary. Protecting institutions of higher education is an essential part of democracy. A crackdown on academic freedom is one of a series of dangerous developments in Hungary under the leadership of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The campaign against the CEU is a highly symbolic move against a vital institution founded to promote the transatlantic values of democracy, openness, and equality of opportunity. Founded in 1991, CEU is a graduate-level university based in Budapest, in partnership with Bard College, and with academic accreditation in Hungary and the State of New York. Because it is a joint American-Hungarian institution, it has support across the political spectrum in the United States and at all levels of our government. Michael Ignatieff, President and Rector of the CEU, thanked the U.S. Ambassador to Hungary David Cornstein as well as the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Congress, the Office of the Governor of New York, and the New York State Education Department for their efforts to secure an agreement certifying CEU for continued operation in Hungary. Ambassador Cornstein took a principled stand in using the #IStandWithCEU hashtag on the embassy website. The Hungarian government, however, has refused to sign this agreement for almost one full year. -

National Government Ethics Summit Speaker Bios David Apol Mr. Apol Is the General Counsel of the U.S. Office of Government Ethi

National Government Ethics Summit Speaker Bios David Apol Mr. Apol is the General Counsel of the U.S. Office of Government Ethics (OGE). Prior to his position as OGE’s General Counsel, Mr. Apol served as the Chief Counsel for Administrative Law at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, leading the administrative law program of a cabinet-level agency. Before that, he served as an Associate General Counsel at OGE, where his accomplishments included both working on ethics law reform in the United States and advising a foreign government on establishing its own ethics laws at a critical time of political change. Prior to coming to OGE, Mr. Apol served as Associate Counsel to the President, advising the President, the First Lady, and senior White House officials on ethics issues and the Presidential nominee financial disclosure program. In that capacity, he had the opportunity to work personally with ethics officials from almost every executive branch agency. Mr. Apol served as an executive branch agency ethics official at the Department of Labor from 1992 to 2000, where he was charged with establishing and then managing a new Department-wide ethics program. Previously, he served as a Counsel for the Senate Ethics Committee from 1987 to 1992. Prior to coming to Washington, Mr. Apol served as a Judge Advocate General Officer in the U.S. Army where he was responsible for ethics, administrative law, international law and contract law. He is a graduate of both Wheaton College and the University of Michigan Law School. Monica Ashar Monica Ashar is an Assistant Counsel in the Ethics Law and Policy Branch at the U.S.