ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS in Association with ADELAIDE FESTIVAL Presents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

Masters File 5

University of Adelaide Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Elder Conservatorium of Music Portfolio of Compositions and Exegesis: Composing for a Choral Spectrum Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (MMus) by Callie Wood August 2008 225 Part B Exegesis Composing for a Choral Spectrum 226 B1 Exegesis: Composing for a choral spectrum. 1.1 RESEARCH QUESTIONS The research questions of this thesis were primarily addressed through practical experiments in choral music composition, which resulted in a portfolio of choral works covering a categorized choral spectrum ranging from very simple choral works for young children, to complex works for adult choirs of a professional standard. 1: What are the limitations for a composer in choice of text, text setting, choral groupings, and instrumental accompaniments when composing for a choral spectrum? 2: What are the limitations for a composer in regard to musicianship skills, aural skills, intonation skills, vocal range and ability when composing for a choral spectrum? Each of the works included in the portfolio addresses a particular aspect, or particular aspects, of the above research questions. To make the compositions especially suited to Australian choirs, the lyrics selected for all of the music have been written by Australian poets. To make the music accessible to a wide range of singers, all of the music for the portfolio is non-religious. Some of the compositions included in the portfolio were rehearsed, performed or recorded, which greatly assisted in the revision stage of the compositional process. However, arranging for all of the works in the portfolio to be performed and recorded was beyond the scope of this thesis. -

SEASON 2017 Adult 2 Concert Package $74 Per Person *Conc 2 Concert Package $60 Per Person SUBSCRIPTION

7 01 SEASON 2 WELCOME TO Recognise the iconic Adelaide bookstore in our We love discovering new music and creating new photographs this year? Good bookstores, good coffee ways of presenting existing music. It keeps us alive and good chamber-music - three of life’s essentials! artistically and, just like a good book, fires our imaginations. 2017 marks our 20th Subscription Series in Adelaide and we begin with one of our favourite composers - We are also delighted to move to our new Adelaide Claudio Monteverdi. Our journey continues through the Hills performance venue, the UKARIA Cultural Centre in year with musical friends Arvo Pärt, Bob Chilcott and Mt Barker - beautiful outlook, welcoming and friendly Carlo Gesualdo and concludes with one of the most atmosphere, wonderfully clear acoustic! loved works in the choral repertory - Handel’s Messiah - Carl Crossin OAM presented in our own intimate ‘chamber’ version within Artistic Director & Conductor the lofty, resonant expanse of St. Peter’s Cathedral. We’re also very excited to present three new works by Adelaide-educated composers Steven Tanoto and Anne Cawrse, and by one of the doyens of Australian composition, Graeme Koehne. PROGRAM 1 SATURDAY 3 JUNE, 6.30PM Pilgrim Church, 12 Flinders Street, Adelaide SUNDAY 4 JUNE, 2.30PM UKARIA Cultural Centre, 119 Williams Road, Mt Barker Summit Conductor Carl Crossin PROGRAM Il Pastor Fido madrigal cycle from Madrigals Books 5 - Claudio Monteverdi A selection of madrigals expressive of the joys and vicissitudes of life by Renaissance masters John Wilbye, John Bennett, Thomas Weelkes, Ludwig Senfl and Michael East Songs and Cries of London Town for chamber choir and piano duet - Bob Chilcott The Cries of London - Orlando Gibbons April in Paris - arr. -

Report of the Executive Director for Calendar Year 2010

Admini.StTalion MBE 148/45 Glenferrie Road Malvern, Vic 3144 Phone: 03 9507 2315 Fax: 03 9507 2316 Email: [email protected] We.hslte: www.mca.org.au ABN 85 070 619 608 Exet::utJve DlredDr Tel: +61 (0)2 9251 3816 Fax: +61 (0)2 9251 3817 Emall: [email protected] Music COundl of Australia Music. Play for life campaign Tel: 02) 4454 3887 or 0439 022 257 Emall: [email protected] Website: www.muslcplayforllfe.org Austnlla's representJJIJ!Ie m the I~ Music Coundl REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FOR CALENDAR YEAR 2010 This report is based on the report to the Council members at the September AGM, updatsd in key aspects to the end of the year. CONTENTS October 2009 to September 2010, with some extension Tn matters such as lists of advocacy A. Purpose of the MCA projects or financial end of year results. B. Highlights of the Year 2009-2010 MCA's work is divided along the lines suggested C. Infonnation Services in the statement of purpose: Information Services, Research, Advocacy and D. Research and Policy Representation, and Projects. E. Advocacy and Representation lnfonnation services F. Projects Music Forum magazine has published an online G. Governance and Administration version as part of a plan to counter falling subscription and advertising income. The print H. In Conclusion version will continue. The Music Forum website Is a sort of MCA media centre with access to all MCA online A. PURPOSE OF THE MCA publications: the weekly eBulletins, two monthly The purpose of the Music COuncil of Australia eNewsletters, the IMC Music World News, and (MCA) is to bring together all sections of the the other eight MCA websTtes. -

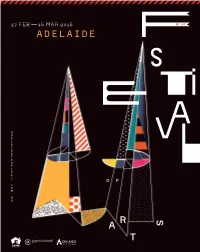

Download Adelaide Festival Guide

WELCOME For the past As well as the maestro, award-winning actor Jonathan Pryce brings his acclaimed 50 Years, the talents to Harold Pinter’s renowned play, The Caretaker, and France’s legendary film ADelaiDE FestiVal actress Isabelle Huppert sheds new light has shone on a Tennessee Williams classic. As well as offering the best in as the Biennial contemporary art from around the world, the Adelaide Festival provides JEWel in the a high-profile, global platform for our local artists. Its commitment to innovation CroWN OF South and inspiration also remains, and includes Australia’s most-loved literature event, Australia’S Adelaide Writers’ Week, the formidable Adelaide artistiC AND International exhibition, and a revitalised party Cultural precinct that serves as the CalenDAR. Festival’s celebratory heart. These significant attractions are but the beginning of a Now, from 2012, the Festival wide-ranging, world-class brings the very best in theatre, program, and they continue dance, opera, literature, music, the Adelaide Festival’s film and the visual arts to Adelaide every reputation for bringing the planet’s year, further enhancing our city as a place foremost artists and productions of pilgrimage for arts lovers the world over. to our doorstep. Among our Festival’s enduring, defining In a fitting send-off to outgoing characteristics are the special events within Artistic Director Paul Grabowsky, its extensive program that remain exclusive 2012 Adelaide Festival promises to to Adelaide, and three internationally- be the most absorbing, most diverse acclaimed artists make their debut and most inspiring Festival yet. I look Australian appearances here in 2012. -

Northern Lights

Northern Lights Subscription concert 1, 2015 Adelaide Chamber Singers Carl Crossin, Artistic Director & Conductor Christie Anderson - Guest Conductor Elizabeth Layton - violin Karl Geiger - organ 6:30pm Saturday 27 June, St Peter’s Cathedral 3:00pm Sunday 28 June, The Village Well Church of Christ, Aldgate Adelaide Chamber Singers Artistic Director & Conductor, Carl Crossin Associate Conductor, Christie Anderson Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Alexandra Bollard Rachel Bruerville David Hamer Andrew Bettison Emma Borgas Victoria Coxhill Andrew Linn Christian Evans Emma Horwood Penny Dally Robin Parkin Christopher Gann Brooke Window Charlie Kelso Martin Penhale Timothy Marks Lachlan Scott Program Eatnemen vuelie Frode Fjellheim (b.1959) Stars Ēriks Ešenvalds (b.1977) Ave Maris Stella Diane Loomer (1940 – 2012) Soloists: Christopher Gann, Lachlan Scott Berliner Messe (excerpts) Arvo Pärt (b.1935) with Karl Geiger, organ Kyrie Gloria Erster Alleluiavers Zweiter Alleluiavers Sanctus Agnus Dei In the Bleak Midwinter Snow (premiere performance) Philip Hall (b.1964) Soloists: Emma Horwood, Alexandra Bollard, Emma Borgas, Andrew Linn & Brooke Window INTERVAL Magnificat Giles Swayne (b.1946) Soloists: Victoria Coxhill, Charlie Kelso, Andrew Linn, Martin Penhale, David Hamer, Robin Parkin, & Alexandra Bollard Ave Maris Stella Andrew Smith (b.1970) Lux aeterna David Hamilton (b.1955) Ave Maria Knut Nystedt (1915 – 2014) featuring Elizabeth Layton, solo violin We beheld once again the stars Z. Randall Stroope (b.1953) About the Program My first visit to Norway - the true north in my mind, was with the Adelaide Chamber Singers in 1996. It was summer and I remember getting sunburned. I have never gone back in the middle of winter and every February in Adelaide I dream about it. -

Requiem Internal Booklet 20/10/06 12:30 PM Page 1

Requiem Internal Booklet 20/10/06 12:30 PM Page 1 ❘ SCULTHORPE ❘ REQUIEM ❘ MY COUNTRY CHILDHOOD • GREAT SANDY ISLAND NEW NORCIA • QUAMBY • EARTH CRY ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA • ARVO VOLMER • JAMES JUDD Requiem Internal Booklet 20/10/06 12:30 PM Page 3 PETER SCULTHORPE b. 1929 CD2 My Country Childhood [15’54] CD1 1 I. Song of the Hills 4’10 Requiem [42’15] 2 II. A Church Gathering 3’26 1 I. Introit 3’00 3 III. A Village Funeral 4’22 2 II. Kyrie 7’00 4 IV. Song of the River 3’56 3 III. Gradual 3’36 5 Earth Cry (abridged version) 5’57 4 IV. Sequence 7’08 5 V. Canticle 9’21 Great Sandy Island [22’47] 6 VI. Sanctus 2’43 6 I. The Sea Coast 2’53 7 VII. Agnus Dei 2’37 7 II. The Boro-ground 3’53 8 III. The Rain-forest 6’21 8 VIII. Communion 6’47 9 IV. The Garrison 3’28 Adelaide Chamber Singers 0 V. Dune Dreaming 6’12 William Barton didjeridu ! New Norcia 5’07 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra Arvo Volmer conductor Quamby (for chamber orchestra) [23’26] @ I. Prelude 3’41 £ II. In the Valley 5’11 $ III. On High Hills 5’20 % IV. At Quamby Bluff 9’14 Total Playing Time 115’26 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra James Judd conductor [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Requiem Internal Booklet 20/10/06 12:30 PM Page 5 CD1 Indigenous chant, leaves no doubt that the work is his call for justice for Australian Aboriginal people, though he chooses not to use the word ‘reconciliation’ for what he is seeking, simply ‘because we were never Requiem (2004) for SATB chorus, didjeridu and orchestra conciled in the first place.’ Since the mid 1950s, death has never been far from Sculthorpe’s music, the nexus between the Australian The Requiem is the longest and most substantial single work Sculthorpe has produced since his television landscape and the dreamtime world beyond. -

Natural Music Including the Annual Carols on Campus Held in Bonython Hall in December

Earthsong Frank Ticheli Frank Ticheli, an American composer, residing in Los Angeles California, known for his orchestral, choral, chamber and concert band works. He is also a Professor of Composition at the University of Southern California Earthsong is one of the very few works that was composed without a commission. It was composed out of Ticheli’s personal needs and longing for peace during the war in Iraq. Ticheli felt he had to write the poem himself because it was not just a poem but a prayer, a plea or wish to seek inner peace in a world tinted by war and hatred. The poem is a declaration of the power of music to heal. Ticheli also adapted the wind ensemble edition of the Earthsong from his choral setting. Come To The Woods Jake Runestad Jake Runestad, a Minneapolis, Minnesota based American composer known more for his opera, orchestral music, choral music and wind ensemble albeit he composed for a wide variety of musical genres and ensembles. Come to the Woods for SATB and piano with text by John Muir was commissioned by Craig Hella Johnson and Conspirare. It was premiered at St. Martin’s Lutheran Church, Austin, Texas on May 9, 2015. Come to the Woods explores Muir’s inspirations from the whispering of the wind, power of a storm, the light, the clouds and all his encounters while exploring the outdoors. Carl Crossin OAM is a graduate of both the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and the University of Adelaide and is widely respected as one of Australia’s leading choral conductors. -

S E a S O N 2 0

ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS SEASON 2014 Welcome to Adelaide Chamber Singers’ 2014 Concert Season. Our successes in Italy, Wales and Austria in 2013 propel us into 2014 on a real high - and we’re off to France in October to perform at the 2014 Polyfollia international choral festival. So, we begin 2014 full of vibrancy and creative energy with virtuoso Baroque choral music of the highest order - the complete motets of J. S. Bach. We love our late night Adelaide Festival concerts in St. Peter’s Cathedral and our subscription series sees us in two beautiful and acoustically rich locations in the city, and in the intimate space of the Church of Epiphany in the Adelaide Hills as we return for the second year. We’re also delighted to collaborate with Adelaide’s own Zephyr Quartet in Darkness & Light, and with theatre and opera director Andy Packer in Monteverdi’s Fire. So, from Palestrina to Pärt, Monteverdi to Maclean, Bach to Whitacre and Zephyr, our 2014 Season - our 29th year of music- making – will see us continuing to do we love. Please join us. Bestissimo! Carl Crossin OAM Artistic Director and Conductor PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH ADELAIDE FESTIVAL MONDAY 3 MARCH & WEDNESDAY 5 MARCH, 10PM St. Peter’s Cathedral, King William Rd, North Adelaide Late Night in The Complete the Cathedral Motets of JS Bach The six motets of J S Bach are amongst the The programs also feature Knut Nystedt’s most glorious - and the most virtuosic - musical deconstruction of Bach’s chorale “Komm, süsser masterworks of the Baroque. ACS presents Bach’s Tod” in Immortal Bach, and music for solo violin complete motets in two 60-minute concerts as performed by one of Australia’s finest Baroque special Adelaide Festival performances. -

Australian Music Calendar Victoria : January – December 2012

australian music calendar Victoria : January – December 2012 The Australian Music Calendar lists events from around Australia which feature music by one or more Australian composers, sound artists or improvisers. Below are details for events in Victoria in 2012. * denotes World premiere ; ** denotes Australian premiere VICTORIA 28 January 2012 - Sacred Stage Venue: Kallista Mechanics Hall - Cnr Church St and Tom Roberts Rd, Kallista, 2pm Program: Jacqui Rutten - New hope* - Cybec 21st Century Australian Composers Program Venue: Iwaki Auditorium - ABC Southbank Centre, 120-130 Southbank Boulevard, South Melbourne, 6:30pm. Program: Simon Charles - Atropos, Lisa Illean - Veils, Daniel Portelli - Finding Kensho, Catherine Sullivan - Vidova Gora - Svitanje, Music by Simon Charles, Lisa Illean, Daniel Portelli, Catherine Sullivan. Performers: Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. 1 February 2012 - Frock Venue: Bennetts Lane Jazz Club - 25 Bennetts Lane, Melbourne, 8.30pm - Seensound Visual/Music Venue: Loop - 23 Meyers Place, Melbourne, 7:30pm Program: Warren Burt - E-PHI (Didn't Care), Brigid Burke - Street line*, Snapper is a feast, Seed*, Mark Pederson - Seed*, Street line*, Jim Denley - Closely Woven Fabrik, Andrew Thomson/Lloyd Barrett - Dorn Kpring, Music by Peter Jovanov, Scott Morrison. Also: Dan Senn and Justin Bradshaw. 5 February 2012 - Syzygy @ Stones of the Yarra Winery Venue: Stones of the Yarra Winery - 14 St Huberts Road, Coldstream, 11am Program: Brenton Broadstock - I touched your glistening tears, Annie Hsieh - Quartet: towards the -

Lunchtime Concert Series Season One

ELDER CONSERVATORIUM OF MUSIC CONCERT 2019 SERIES music.adelaide.edu.au/concerts WELCOME While always maintaining the rich heritage and aspirations of the traditional European-style Conservatorium of its origins, the Elder Conservatorium of Music has grown in size and scope to become a truly Australian, 21st - century music training institution. The Conservatorium teaches music performers, creators, educators and researchers across a wide variety of styles and genres: Classical, Jazz, Opera, Pop, Rock, Choral, Electronica, World and Film Music to name but a few. Our performance staff and students have curated for your enjoyment a wonderful concert series that represents a vibrant sample of the broad world of music we at the Conservatorium inhabit and cherish every day. The Elder Hall is the spiritual home of the Conservatorium and the concerts we present here are the most significant and public expression of our musical mission. We are delighted to share our music making with you and thank you for the support and encouragement your attendance at these concerts represents. THE ELDER Professor Graeme Koehne AO CONSERVATORIUM Director, Elder Conservatorium of Music HAS BEEN THE HEART OF MUSICAL CULTURE IN ADELAIDE FOR OVER 130 YEARS. 2 The Elder Conservatorium of Music Concert Series 2019 3 LUNCHTIME CONCERT SERIES SEASON ONE Friday 22 March Friday 5 April SOUND THE ORGAN RAGS AND RHAPSODIES Kemp English organ Ensemble Liaison All concerts in Elder Hall Music by Mons Leidvin Takle Kats-Chernin Ballade, Zee Rag, Russian Rag Novacek Four Rags for Two Jons Doors open at 12:30pm Our 2019 season roars to life with the mighty Gershwin (arr. -

A Longitudinal Study of Australian Choral Experts

Australian Choral Conductors and Current Choral Practice: A Longitudinal Study of Australian Choral Experts Author Wyvill, Janet Published 2012 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3109 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367961 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University Brisbane, Australia Australian Choral Conductors and Current Choral Practice: A Longitudinal Study of Australian Choral Experts A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Janet Wyvill 2012 AUSTRALIAN CHORAL CONDUCTORS ii Abstract This dissertation explores the nature of the Australian Choral Conductor. Through survey, interview and case study, the research aimed to reveal the attributes of the Australian Choral Conductor, particularly in relation to the skills and experiences that contribute to a conductor becoming an expert. The Australian Choral Conductor, it could be argued, is under valued and little understood. There are very few opportunities for Australian experts to remain as full time choral conductors within their own country. In some cases Australian conductors have moved overseas to take up choral conducting positions, and in the process have gained international recognition. This research investigated if there was a particular pathway to becoming a choral conductor, and if there were opportunities to remain as such within Australia. The research arose out of three defining moments in Australian choral music. These were the 1998 National Strategic Plan for Choral Development; and the 1998 ANCA survey research entitled ‘So you want to be a choral conductor?’ and the 1996 World Symposium of Choral Music in Sydney.