A Longitudinal Study of Australian Choral Experts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Music Calendar South Australia 2011

australian music calendar South Australia 2011 The Australian Music Calendar lists events from around Australia which feature music by one or more Australian composers, sound artists or improvisers. Events are sorted by state and further information on each event can be found online at http://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/calendar * denotes World premiere ; ** denotes Australian premiere SOUTH AUSTRALIA 26 February 2011 - Australian String Quartet : Performance in Campbell Park Venue: Campbell Park Station - Lake Albert, Meningie, 7pm Program: Graeme Koehne - Shaker dances. Also: Glazunov, Boccherini. Performers: Australian String Quartet. Tickets: $70. Phone number for further information: 1800 040 444. 10 March 2011 - Australian String Quartet: Shaker Dances Venue: Adelaide Town Hall - 128 King William St, Adelaide, 7pm Program: Graeme Koehne - String quartet no. 2. Also: Boccerini, Shostakovich, Glazunov. Performers: Australian String Quartet. Tickets: Adult $57 / Concession $43 / Student $22 (service fee applies). 20 March 2011 - Masquerade : Kegelstatt Ensemble Venue: Pilgrim Church - 12 Flinders St, Adelaide, 3.00pm Program: Paul Stanhope - Shadow dancing, Brett Dean - Night window. Also: Kurtag; Mozart. Performers: Leigh Harold, Kegelstatt Ensemble, Stephanie Wake-Dyster, Anna Webb, Kegelstatt Ensemble. Tickets: $25/$18. 27 March 2011 - AdYO: Beginnings Venue: Elder Hall - Elder Conservatorium of Music, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, 6.30pm Program: Natalie Williams - Fourth alarm. Also: Respighi, Sejourne. Performers: Adelaide Youth Orchestra, Keith Crellin. Tickets: Adults: $25 | Concession: $20 | Students: $10 | Group (8+): $22 | Family: $60. Phone number for further information: 131246 (Tickets). 1 April 2011 - Adelaide Symphony Orchestra: Grandage premiere Venue: Adelaide Town Hall - 128 King William St, Adelaide, 8pm Program: Iain Grandage - Spindle*. Also: Lalo, Dvorak, Tchaikovsky, Elgar. -

Tivoli Dances

476 6502 GRAEME KOEHNE tivoli dances TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA The selection of pieces recorded here forms a on-stage by a piano quintet. The ballet explored survey, ranging across 20 years, of Graeme themes of the continuities between the past Koehne’s engagement with an aesthetic of the and the present, and Murphy called it Old ‘lighter touch’. Graeme’s turn towards ‘lightness’ Friends, New Friends. Graeme (Koehne) chose began in the early 1980s, when he moved from to write in a ‘Palm Court’ style both because it Adelaide to the university town of Armidale in suited the ensemble and had an appropriately New South Wales. Here he encountered, on the nostalgic quality – hence the title Palm Court Graeme Koehne b. 1956 one hand, a withdrawal from the support Suite when the work appears without dancers. Tivoli Dances [20’39] network of Adelaide’s then thriving ‘new music’ The piece was the surprise success of the 1 I. Santa Ana Freeway 4’46 scene; and on the other, a small, close-knit but program and Murphy decided to expand it into a 2 II. Forgotten Waltz (Tivoli Memories) 5’52 musically active community. The change of social full evening work called Nearly Beloved, which 3 III. Salvation Hymn and Whistling Song 5’10 environment prompted Graeme to re-evaluate his has had several seasons, including at the Créteil 4 IV. Vamp ’Til Ready 4’51 aesthetic priorities, leading progressively to his Maison des Arts. rejection of the ideology of ‘heroic’ modernism Shaker Dances [21’14] The return to simplicity and vernacular musical in favour of a new, more modest aim of 5 I. -

ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS in Association with ADELAIDE FESTIVAL Presents

ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS in association with ADELAIDE FESTIVAL presents LATE NIGHT IN THE CATHEDRAL The Tears of Saint Peter Wednesday 13 March 2019 @ 8pm Friday 15 March 2019 @ 10pm St. Peter’s Cathedral, North Adelaide PROGRAM Lagrime di San Pietro Orlando di Lasso …and Peter went out and wept bitterly (première performance) Carl Crossin four interludes for soprano & cello Miserere mei, Deus Gregorio Allegri Adelaide Chamber Singers Greta Bradman soprano Simon Cobcroft cello Carl Crossin conductor PROGRAM Please reserve your applause until the end of the Lagrime di San Pietro and then until the end of the Allegri Miserere. The program will proceed without interval Lagrime di San Pietro (The Tears of St. Peter) Orlando di Lasso Interlude 1 1 Il magnanimo Pietro 2 Ma gli archi 3 Tre volte haveva 4 Qual a l’incontro 5 Giovane donna 6 Cosi talhor 7 Ogni occhio del signor Interlude 2 8 Nessun fedel trovai 9 Chi ad una ad una 10 Come falda di neve 11 E non fu il pianto suo 12 Quel volto 13 Veduto il miser Interlude 3 14 E vago d’incontrar 15 Vattene vita va 16 O vita troppo rea 17 A quanti già felici 18 Non trovava mia fé 19 Queste opre e piu 20 Negando il mio signor Interlude 4 21 Vide homo Miserere mei, Deus Gregorio Allegri Page 2 of 16 ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS Carl Crossin, Conductor LASSUS – LAGRIME DI SAN PIETRO ALLEGRI – MISERERE MEI, DEUS Soprano 1 Solo Quartet Alexandra Bollard Greta Bradman (Soprano 1) Brooke Window Emma Borgas (Soprano 2) Christie Anderson (Alto) Soprano 2 Christian Evans (Baritone) Christie Anderson Emma Borgas -

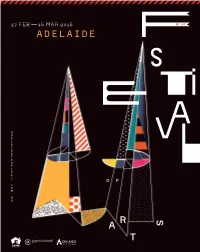

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

The Australian Symphony of the 1950S: a Preliminary Survey

The Australian Symphony of the 1950s: A Preliminary survey Introduction The period of the 1950s was arguably Australia’s ‘Symphonic decade’. In 1951 alone, 36 Australian symphonies were entries in the Commonwealth Jubilee Symphony Competition. This music is largely unknown today. Except for six of the Alfred Hill symphonies, arguably the least representative of Australian composition during the 1950s and a short Sinfonietta- like piece by Peggy Glanville-Hicks, the Sinfonia da Pacifica, no Australian symphony of the period is in any current recording catalogue, or published in score. No major study or thesis to date has explored the Australian symphony output of the 1950s. Is the neglect of this large repertory justified? Writing in 1972, James Murdoch made the following assessment of some of the major Australian composers of the 1950s. Generally speaking, the works of the older composers have been underestimated. Hughes, Hanson, Le Gallienne and Sutherland, were composing works at least equal to those of the minor English composers who established sizeable reputations in their own country.i This positive evaluation highlights the present state of neglect towards Australian music of the period. Whereas recent recordings and scores of many second-ranking British and American composers from the period 1930-1960 exist, almost none of the larger works of Australians Robert Hughes, Raymond Hanson, Dorian Le Gallienne and their contemporaries are heard today. This essay has three aims: firstly, to show how extensive symphonic composition was in Australia during the 1950s, secondly to highlight the achievement of the main figures in this movement and thirdly, to advocate the restoration and revival of this repertory. -

Compositions by Matthew Hindson

Compositions by Matthew Hindson Matthew Hindson, M. Mus. (Melb), B.Mus. (Hons.) (Syd) A folio of original musical compositions and accompanying introductory essay submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music University of Sydney July 2001 Volume I: Introductory Essay N.B.: This submission comprises a folio of creative work. It is in two volumes and includes two accompanying compact discs, musical scores and an introductory essay. © Matthew Hindson Certification I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due references has been made in the text. ____________________________ Matthew Hindson 31st July 2001 Possible works to be included on the CD and in the folio of compositions: • Speed (1996) – orchestra – 16 minutes [YES] • RPM (1996) – orchestra – 4 minutes [DO I NEED THIS ONE?] • Techno-Logic (1997) – string quartet – [no recording] • technologic 1-2 (1997) – string orchestra – 8 minutes [YES] • Night Pieces (1998) – soprano saxophone and piano – 8 minutes [YES] • Rush – guitar and string quartet – 9 minutes [YES] • In Memoriam: Concerto for Amplified Cello and Orchestra (2000) – 34 minutes [YES] • Moments of Plastic Jubilation (2000)– solo piano – 5 minutes [???] • Always on Time (2001) – violin and cello – 2 minutes [???] • The Rave and the Nightingale (2001) – string qt and string orch – 18 min. [???] [CONCERNS: IS THIS CONCENTRATED TOO MUCH ON ORCHESTRAL AND STRING WORKS? – THEY ARE THE BEST PIECES THOUGH] Chapter 1: Introduction As an Australian composer living at the end of the twentieth / start of the twenty-first centuries, I believe that there is an obligation embedded in musical art that is created in this era: to impart and explore musical and extra-musical ideas that are directly relevant to, and representative of, the society in which I live. -

Beethoven: the Piano Concertos

ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEASON 2019 SPECIAL EVENT Beethoven: The Piano Concertos June Wed 5 – Sat 15 7pm Elder Hall CONTENTS ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES 3 Nicholas Carter Conductor Jayson Gillham Piano CONCERT ONE 5 June Wed 5, 7pm CONCERT TWO 11 June Sat 8, 7pm CONCERT THREE 16 June Wed 12, 7pm CONCERT FOUR 21 June Sat 15, 7pm ABC Classic is recording the concertos for CD release in early 2020 – the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. The ASO acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past, present and future. 2 ARTIST BIOGRAPHY Nicholas Carter Conductor Newly appointed as Chief Conductor of the In Australia, he collaborates regularly with Stadttheater Klagenfurt and the Kärntner many of the country’s leading orchestras Sinfonieorchester, Nicholas Carter will lead and ensembles and led the 2018 Adelaide three new productions per season and Festival’s acclaimed full staging of Brett appear regularly in the orchestra’s concert Dean’s Hamlet. Past engagements have series. In his first season, he conducts included the Melbourne, Sydney, West Rusalka, La Clemenza di Tito and Pelléas Australian, Queensland and Tasmanian et Mélisande, and concert programmes Symphony Orchestras with soloists such include Haydn’s Die Schöpfung and Mahler’s as Michelle de Young, Simon O’Neill, Alina Symphony No. 1. Ibragimova, Alexander Gavrylyuk and James Ehnes; also galas with Maxim Vengerov Since his appointment as Principal (Queensland Symphony) and Anne Sofie von Conductor of the Adelaide Symphony Otter (Sydney Symphony). -

Masters File 5

University of Adelaide Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Elder Conservatorium of Music Portfolio of Compositions and Exegesis: Composing for a Choral Spectrum Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (MMus) by Callie Wood August 2008 225 Part B Exegesis Composing for a Choral Spectrum 226 B1 Exegesis: Composing for a choral spectrum. 1.1 RESEARCH QUESTIONS The research questions of this thesis were primarily addressed through practical experiments in choral music composition, which resulted in a portfolio of choral works covering a categorized choral spectrum ranging from very simple choral works for young children, to complex works for adult choirs of a professional standard. 1: What are the limitations for a composer in choice of text, text setting, choral groupings, and instrumental accompaniments when composing for a choral spectrum? 2: What are the limitations for a composer in regard to musicianship skills, aural skills, intonation skills, vocal range and ability when composing for a choral spectrum? Each of the works included in the portfolio addresses a particular aspect, or particular aspects, of the above research questions. To make the compositions especially suited to Australian choirs, the lyrics selected for all of the music have been written by Australian poets. To make the music accessible to a wide range of singers, all of the music for the portfolio is non-religious. Some of the compositions included in the portfolio were rehearsed, performed or recorded, which greatly assisted in the revision stage of the compositional process. However, arranging for all of the works in the portfolio to be performed and recorded was beyond the scope of this thesis. -

SEASON 2017 Adult 2 Concert Package $74 Per Person *Conc 2 Concert Package $60 Per Person SUBSCRIPTION

7 01 SEASON 2 WELCOME TO Recognise the iconic Adelaide bookstore in our We love discovering new music and creating new photographs this year? Good bookstores, good coffee ways of presenting existing music. It keeps us alive and good chamber-music - three of life’s essentials! artistically and, just like a good book, fires our imaginations. 2017 marks our 20th Subscription Series in Adelaide and we begin with one of our favourite composers - We are also delighted to move to our new Adelaide Claudio Monteverdi. Our journey continues through the Hills performance venue, the UKARIA Cultural Centre in year with musical friends Arvo Pärt, Bob Chilcott and Mt Barker - beautiful outlook, welcoming and friendly Carlo Gesualdo and concludes with one of the most atmosphere, wonderfully clear acoustic! loved works in the choral repertory - Handel’s Messiah - Carl Crossin OAM presented in our own intimate ‘chamber’ version within Artistic Director & Conductor the lofty, resonant expanse of St. Peter’s Cathedral. We’re also very excited to present three new works by Adelaide-educated composers Steven Tanoto and Anne Cawrse, and by one of the doyens of Australian composition, Graeme Koehne. PROGRAM 1 SATURDAY 3 JUNE, 6.30PM Pilgrim Church, 12 Flinders Street, Adelaide SUNDAY 4 JUNE, 2.30PM UKARIA Cultural Centre, 119 Williams Road, Mt Barker Summit Conductor Carl Crossin PROGRAM Il Pastor Fido madrigal cycle from Madrigals Books 5 - Claudio Monteverdi A selection of madrigals expressive of the joys and vicissitudes of life by Renaissance masters John Wilbye, John Bennett, Thomas Weelkes, Ludwig Senfl and Michael East Songs and Cries of London Town for chamber choir and piano duet - Bob Chilcott The Cries of London - Orlando Gibbons April in Paris - arr. -

Heaven's Burning Music Credits

music by Graeme Koehne and Michael Atkinson Music "The In Crowd" written by Billy Page, performed by Bryan Ferry published by Hill & Range Songs Inc./J. Albert & Son Pty. Ltd. courtesy of EG Records & Virgin Records Australia Pty. Ltd. "The Honeydripper" written by Joe Liggins, performed by Jo Jo Zep & The Falcons published by Northern Music Corporation, administered by MCA Music Australia Pty. Ltd. courtesy of EMI Music Australia Pty. Ltd. "Bayou Pon Pon" Trad. arrangement by Menard/Le Juene/Smith, performed by Le Trio Cadien published by Happy Valley Music, courtesy of Rounder Records "Another Spring, Another Love" written by Gloria Shayne/Noel Paris, performed by Marlene Dietrich, published by Robert Mellin Inc. administered by Warner/Chappell Music Aus. Pty. Ltd. courtesy of MCA Records, by arrangement with Universal Special Markets "Soave Sia Il Vento" from "Cosi fan Tutte" written by W. A. Mozart, performed by Lucia Pohl/Brigitta Fassbaender, Tom Krause and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Ivan Kertesz, courtesy of Decca Record Company Ltd (U.K.), under licence from PolyGram Pty. Ltd. "Song for a Dreamer" written by Robin Trower/Keith Reid, performed by Procol Harum published by Bluebeard Music/PolyGram Music Publishing courtesy of EMI Records Ltd (U.K.) "Surfin' Bird" written by Alfred Frazier/John Earl Harris/Carl Whyte/Turner Wilson Jnr. performed by The Trashmen, published by EMI Music Publishing Aust. Pty. Ltd. courtesy of Sundazed Music Inc. "Don't Forget to Remember" written by Barry & Maurice Gibb, performed by The Bee Gees published by Gibb Bros. Music/BMG, courtesy of PolyGram International BV, under licence from PolyGram Pty. -

Report of the Executive Director for Calendar Year 2010

Admini.StTalion MBE 148/45 Glenferrie Road Malvern, Vic 3144 Phone: 03 9507 2315 Fax: 03 9507 2316 Email: [email protected] We.hslte: www.mca.org.au ABN 85 070 619 608 Exet::utJve DlredDr Tel: +61 (0)2 9251 3816 Fax: +61 (0)2 9251 3817 Emall: [email protected] Music COundl of Australia Music. Play for life campaign Tel: 02) 4454 3887 or 0439 022 257 Emall: [email protected] Website: www.muslcplayforllfe.org Austnlla's representJJIJ!Ie m the I~ Music Coundl REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FOR CALENDAR YEAR 2010 This report is based on the report to the Council members at the September AGM, updatsd in key aspects to the end of the year. CONTENTS October 2009 to September 2010, with some extension Tn matters such as lists of advocacy A. Purpose of the MCA projects or financial end of year results. B. Highlights of the Year 2009-2010 MCA's work is divided along the lines suggested C. Infonnation Services in the statement of purpose: Information Services, Research, Advocacy and D. Research and Policy Representation, and Projects. E. Advocacy and Representation lnfonnation services F. Projects Music Forum magazine has published an online G. Governance and Administration version as part of a plan to counter falling subscription and advertising income. The print H. In Conclusion version will continue. The Music Forum website Is a sort of MCA media centre with access to all MCA online A. PURPOSE OF THE MCA publications: the weekly eBulletins, two monthly The purpose of the Music COuncil of Australia eNewsletters, the IMC Music World News, and (MCA) is to bring together all sections of the the other eight MCA websTtes.