Requiem Internal Booklet 20/10/06 12:30 PM Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erkki-Sven Tüür

© Kaupo Kikkas Erkki-Sven Tüür Contemporary BIOGRAPHIE Erkki-Sven Tüür Mit einem breit gefächerten musikalischen Hintergrund und einer Vielzahl von Interessen und Einflüssen ist Erkki- Sven Tüür einer der einzigartigsten Komponisten der Zeitgenössischen Musik. Tüür hat 1979 die Rockgruppe In Spe gegründet und bis 1983 für die Gruppe als Komponist, Flötist, Keyboarder und Sänger gearbeitet. Als Teil der lebhaften Szene der Zeitgenössischen Musik Estlands unternahm er instrumentale Studien an der Tallinn Music School, studierte Komposition mit Jaan Rääts an der Estonian Academy of Music und erhielt Unterricht bei Lepo Sumera. Intensive energiereiche Transformationen bilden den Hauptcharakter von Tüürs Werken, wobei instrumentale Musik im Vordergrund seiner Arbeit steht. Bis heute hat er neun Sinfonien, Stücke für Sinfonie- und Streichorchester, neun Instrumentalkonzerte, ein breites Spektrum an Kammermusikwerken und eine Oper komponiert. Tüür möchte mit seiner Musik existenzielle Fragen aufwerfen, vor allem die Frage: „Was ist unsere Aufgabe?“ beschäftigt ihn. Er stellte fest, dass dies eine wiederkehrende Frage von Denkern und Philosophen verschiedener Länder ist. Eins seiner Ziele ist es, die kreative Energie des Hörers zu erreichen. Tüür meint, die Musik als eine abstrakte Form von Kunst ist dazu fähig, verschiedene Visionen für jeden von uns und jedes individuelle Wesen zu erzeugen, denn wir sind alle einzigartig. Sein Kompositionsansatz ähnelt der Art und Weise, mit der ein Architekt ein mächtiges Gebäude wie eine Kathedrale, ein Theater oder einen anderen öffentlichen Ort entwirft. Er meint dennoch, dass die Verantwortung eines Komponisten über die eines Architekten hinausgeht, weil er Drama innerhalb des Raums mit verschiedenen Charakteren und Kräften konstruiert und dabei eine bestimmte, lebende Form von Energie kreiert. -

LS17.17022-Program-Web

ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO The CSO is assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body New Combination “Bean” Lorry No.341 commissioned 31st December 1925. 115 YEARS OF POWERING PROGRESS TOGETHER Since 1901, Shell has invested in large projects which have contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy. We value our partnerships with communities, governments and industry. And celebrate our longstanding partnership with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. shell.com.au Photograph courtesy of The University of Melbourne Archives 2008.0045.0601 SHA3106__CSO_245x172_V3.indd 1 20/09/2016 2:53 PM ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO Wednesday 17 May & Thursday 18 May, 2017 Llewellyn Hall, ANU 7.30pm Conductor Stanley Dodds Cello Umberto Clerici ----- HAYDN: Overture to L’isola disabitata (The Desert Island), Hob 28/9 8’ SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 25’ 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Langsam 3. Sehr lebhaft INTERMISSION SCULTHORPE: String Sonata No. 3 (Jabiru Dreaming) 8’ 1 Deciso 2 Liberamente – Estatico BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, op. 90 33’ 1. Allegro con brio 2. Andante 3. Poco allegretto 4. Allegro Please note: this program is correct at time of printing, however it is subject to change without notice. Umberto Clerici’s performance is supported by the Embassy of Italy in Canberra, Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Sydney and Schiavello enterprise Cover photo by Sarah Walker Sarah Cover photo by 17022 SEASON 2017 ActewAGL Llewellyn Series: Cello, Horn, Violin “Music -

Recipients of Honoris Causa Degrees and of Scholarships and Awards 1999

Recipients of Honoris Causa Degrees and of Scholarships and Awards 1999 Contents HONORIS CAUSA DEGREES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE- Members of the Royal Family 1 Other Distinguished Graduates 1-9 SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS- The Royal Commission of the Exhibition of 1851 Science Research Scholarships 1891-1988 10 Rhodes Scholars elected for Victoria 1904- 11 Royal Society's Rutherford Scholarship Holders 1952- 11 Aitchison Travelling Scholarship (from 1950 Aitchison-Myer) Holders 1927- 12 Sir Arthur Sims Travelling Scholarship Holders 1951- 12 Rae and Edith Bennett Travelling Scholarship Holders 1979- 13 Stella Mary Langford Scholarship Holders 1979- 13 University of Melbourne Travelling Scholarships Holders 1941-1983 14 Sir William Upjohn Medal 15 University of Melbourne Silver Medals 1966-1985 15 University of Melbourne Medals (new series) 1987 - Silver 16 Gold 16 31/12/99 RECIPIENTS OF HONORIS CAUSA DEGREES AND OF SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS Honoris Causa Degrees of the University of Melbourne (Where recipients have degrees from other universities this is indicated in brackets after their names.) MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 1868 His Royal Highness Prince Alfred Ernest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh (Edinburgh) LLD 1901 His Royal Highness Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert, Duke of York (afterwards King George V) (Cambridge) LLD 1920 His Royal Highness Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VIII) (Oxford) LLD 1927 His Royal Highness Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, -

Here Has Been a Steady Production of Operas Since the Season 1918/19

ESTONIAN NATIONAL OPERA Article provided by the Estonian National Opera At a glance The roots of the Estonian National Opera go back to 1865, when the song and drama society “Estonia” was founded. In 1906, the society became the basis for a professional theatre. The ballet troupe began regular work in 1926, but the first full-length ballet, Delibes’s “Coppélia” was performed in 1922 already. Since 1998, the theatre is officially named the Estonian National Opera. Estonian National Ballet that operates under Estonian National Opera was founded in 2010. The Artistic Director and Chief Conductor is Vello Pähn, the Artistic Director of the Estonian National Ballet is Thomas Edur and the General Manager is Aivar Mäe. The theatre’s repertoire includes classical and contemporary operas, ballets, operettas and musicals. In addition, different concerts and children’s performances are delivered and compositions of Estonian origin staged. Estonian National Opera is a repertory theatre, giving 350 performances and concerts a year, being famous for its tradition of annual concert performances of rarely staged operas, such as Alfredo Catalani’s “La Wally”, Verdi’s “Simon Boccanegra”, Rossini’s “Guillaume Tell”, Bizet’s “Les pêcheurs de perles”, Bellini’s “I Capuleti e i Montecchi”, “I puritani” and “Norma”, Rimsky-Korsakov’s “The Tsar’s Bride” and “Snegurochka”, Strauss’ “Der Rosenkavalier”, etc. History of the Estonian National Opera In 1865, the song and drama society “Estonia” was founded in Tallinn. Acting was taken up in 1871. From 1895 onwards the society began to stage plays regularly, which usually included singing and dancing. In 1906, the society became the basis for a professional theatre called “Estonia Theatre” founded by the directors and actors Paul Pinna and Theodor Altermann. -

Handbook, 1957

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE FACULTY OF MUSIC HANDBOOK, 1957 MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS Page numbers are not in sequence. This is how they appear in the publication UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE CONSERVATORIUM OF MUSIC Established 1894 t. Director—T ORMOND Рковнssок 0F Music, SIR BERNARD HEINZE, К В LL.D.нк (British Columbia), Mus. Doc. (W.A.), M.A., F.R.C.M., Degré Supérieur, Schola Cantorum, Paris. Vice-Director—REVEREND PERCY JONES, Ph.D., Mus.Doc. Registrar of the University—F. H. JOHNSTON, B.A., B.Com., L.C.A., J.P. Secretary—IAN PAULL FIDDIAN, Barrister and Solicitor. THE ORMOND CHAIR OF MUSIC AND THE CONSERVATORIUM The Chair of Music was founded in the University of Melbourne by the generous endowment (f20,000) of the late Mr. Francis Ormond in 1891. Three years later, in 1894, the Conservatorium was established. THE BUILDING The present building consists of twenty teaching rooms, a finе lecture hall, concert hall (known as Melba Hall), Director's room, administrative offices, library, social room and staff and students' rooms. AIM OF THE CONSERVATORIUM The chief aim of the Conservatorium is co provide a general course of musical education, while provision is also made for specialization in any particular subject. In the absence, on leave, of Mr. Henri Touzeau, Mr. Keith Humble has directed the orchestra. A programme was provided for the National Council of Women at the Melbourne Town Hall, and by the end of the year three concerts will have been given in Melba Hall. At two of these concerts a number of students will have had an opportunity to appear as soloists with the orchestra. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Come and Explore Unknown Music with Us by Joining the Toccata Discovery Club

Recorded in the Estonia Concert Hall, Tallinn, on 11–12 January 2012 (Symphony No. 3) and 29 February 2012 (Lamento) and in The Fraternity Hall, The House of Blackheads, Tallinn, on 2 March 2012 (Sextet). Producer-engineer: Tanel Klesment Thanks to the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra and Tallinn Chamber Orchestra for their participation in this recording Cover photograph of Mihkel Kerem by Pål Solbakk Booklet text by Mihkel Kerem Session photographs by Mait Jüriado Design and lay-out: Paul Brooks, Design & Print, Oxford Executive producer: Martin Anderson TOCC 0173 © 2013, Toccata Classics, London P 2013, Toccata Classics, London Come and explore unknown music with us by joining the Toccata Discovery Club. Membership brings you two free CDs, big discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings and Toccata Press books, early ordering on all Toccata releases and a host of other benefits for a modest annual fee of £20. You start saving as soon as you join. You can sign up online at the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com. Toccata Classics CDs are also available in the shops and can be ordered from our distributors around the world, a list of whom can be found at www.toccataclassics.com. If we have no representation in your country, please contact: Toccata Classics, 16 Dalkeith Court, Vincent Street, London SW1P 4HH, UK Tel: +44/0 207 821 5020 Fax: +44/0 207 834 5020 E-mail: [email protected] 2010. Since 2002 Paavo Järvi has been Artistic Adviser of the orchestra. The Orchestra regularly records music for Estonian Radio and has co-operated with such companies as BIS, Antes Edition, Globe, Signum, Ondine, Finlandia Records, Consonant Works and Melodiya. -

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild Alice Bennett © 2012 Statement of Responsibility: This document does not contain any material, which has been accepted for the award of any other degree from any university. To the best of my knowledge, this document does not contain any material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference is given. Candidate: Alice Bennett Supervisor: Dr. Joel Crotty Signed:____________________ Date:____________________ 2 Contents Statement of Responsibility: ................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Literature Review ................................................................................................................................ 9 Chapter Outlines ............................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter Two ......................................................................................................................................... -

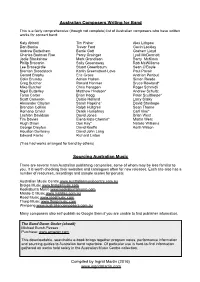

Australian Composers & Sourcing Music

Australian Composers Writing for Band This is a fairly comprehensive (though not complete) list of Australian composers who have written works for concert band: Katy Abbott Tim Fisher Alex Lithgow Don Banks Trevor Ford Gavin Lockley Andrew Batterham Barrie Gott Graham Lloyd Charles Bodman Rae Percy Grainger Lyall McDermott Jodie Blackshaw Mark Grandison Barry McKimm Philip Bracanin Sally Greenaway Rob McWilliams Lee Bracegirdle Stuart Greenbaum Sean O’Boyle Brenton Broadstock Karlin Greenstreet-Love Paul Pavoir Gerard Brophy Eric Gross Andrian Pertout Colin Brumby Adrian Hallam Simon Reade Greg Butcher Ronald Hanmer Bruce Rowland* Mike Butcher Chris Henzgen Roger Schmidli Nigel Butterley Matthew Hindson* Andrew Schultz Taran Carter Brian Hogg Peter Sculthorpe* Scott Cameron Dulcie Holland Larry Sitsky Alexander Clayton Sarah Hopkins* David Stanhope Brendan Collins Ralph Hultgren Sean Thorne Romano Crivici Derek Humphrey Carl Vine* Lachlan Davidson David Jones Brian West Tim Davies Elena Kats-Chernin* Martin West Hugh Dixon Don Kay* Natalie Williams George Dreyfus David Keeffe Keith Wilson Houston Dunleavy David John Lang Edward Fairlie Richard Linton (*has had works arranged for band by others) Sourcing Australian Music There are several main Australian publishing companies, some of whom may be less familiar to you. It is worth checking their websites and catalogues often for new releases. Each site also has a number of resources, recordings and sample scores for perusal. Australian Music Centre www.australianmusiccentre.com.au Brolga Music www.brolgamusic.com Kookaburra Music www.kookaburramusic.com Middle C Music www.middlec.com.au Reed Music www.reedmusic.com Thorp Music www.thorpmusic.com Wirripang www.australiancomposers.com.au Many composers also self-publish so Google them if you are unable to find publisher information. -

ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS in Association with ADELAIDE FESTIVAL Presents

ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS in association with ADELAIDE FESTIVAL presents LATE NIGHT IN THE CATHEDRAL The Tears of Saint Peter Wednesday 13 March 2019 @ 8pm Friday 15 March 2019 @ 10pm St. Peter’s Cathedral, North Adelaide PROGRAM Lagrime di San Pietro Orlando di Lasso …and Peter went out and wept bitterly (première performance) Carl Crossin four interludes for soprano & cello Miserere mei, Deus Gregorio Allegri Adelaide Chamber Singers Greta Bradman soprano Simon Cobcroft cello Carl Crossin conductor PROGRAM Please reserve your applause until the end of the Lagrime di San Pietro and then until the end of the Allegri Miserere. The program will proceed without interval Lagrime di San Pietro (The Tears of St. Peter) Orlando di Lasso Interlude 1 1 Il magnanimo Pietro 2 Ma gli archi 3 Tre volte haveva 4 Qual a l’incontro 5 Giovane donna 6 Cosi talhor 7 Ogni occhio del signor Interlude 2 8 Nessun fedel trovai 9 Chi ad una ad una 10 Come falda di neve 11 E non fu il pianto suo 12 Quel volto 13 Veduto il miser Interlude 3 14 E vago d’incontrar 15 Vattene vita va 16 O vita troppo rea 17 A quanti già felici 18 Non trovava mia fé 19 Queste opre e piu 20 Negando il mio signor Interlude 4 21 Vide homo Miserere mei, Deus Gregorio Allegri Page 2 of 16 ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGERS Carl Crossin, Conductor LASSUS – LAGRIME DI SAN PIETRO ALLEGRI – MISERERE MEI, DEUS Soprano 1 Solo Quartet Alexandra Bollard Greta Bradman (Soprano 1) Brooke Window Emma Borgas (Soprano 2) Christie Anderson (Alto) Soprano 2 Christian Evans (Baritone) Christie Anderson Emma Borgas -

INSIDE the MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE at 75 by John Clare*

INSIDE THE MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE AT 75 by John Clare* __________________________________________________ INSIDE THE MUSICIAN is a series of articles on the Music Trust of Australia website by music people of all kinds, revealing something about their musical worlds and how they experience them. This article appeared on June 5, 2016. To read this on that website, go to this link http://musictrust.com.au/loudmouth/inside-the-musician-john-clare-75/ o come in from a wide or oblique angle, I need to apologise briefly that my writing is not what it was. There is no excuse, but a reason of sorts. Over the T past few years I have lost a son and a sister, the wonderful old Chinese lady upstairs who died and was replaced by a crazy and nasty woman who fire bombed my flat while I was visiting my daughter in Brisbane. And more, but we’ll leave that. Perhaps this stress and distress is behind my two strokes and a triple A operation (aortic aneurism in the aorta) which comprehensively relieved me of my memory for a while. Concentration is difficult and death seems often to be hovering. Yet strangely I am very fit and can race up very steep hills on my bike or grind up on the seat. It is when I am lying down and for some time afterward that it surrounds me. We’ll leave it at that. More important than that is how music sounds and what it means in what may well be the end days. Mine anyway. Like vapour trails soaring straight up at space from the horizon, or so it seems, but finding the curvature of the earth almost directly above. -

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts.