SCORING ESSINGTON: Composition, Comprovisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LS17.17022-Program-Web

ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO The CSO is assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body New Combination “Bean” Lorry No.341 commissioned 31st December 1925. 115 YEARS OF POWERING PROGRESS TOGETHER Since 1901, Shell has invested in large projects which have contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy. We value our partnerships with communities, governments and industry. And celebrate our longstanding partnership with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. shell.com.au Photograph courtesy of The University of Melbourne Archives 2008.0045.0601 SHA3106__CSO_245x172_V3.indd 1 20/09/2016 2:53 PM ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO Wednesday 17 May & Thursday 18 May, 2017 Llewellyn Hall, ANU 7.30pm Conductor Stanley Dodds Cello Umberto Clerici ----- HAYDN: Overture to L’isola disabitata (The Desert Island), Hob 28/9 8’ SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 25’ 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Langsam 3. Sehr lebhaft INTERMISSION SCULTHORPE: String Sonata No. 3 (Jabiru Dreaming) 8’ 1 Deciso 2 Liberamente – Estatico BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, op. 90 33’ 1. Allegro con brio 2. Andante 3. Poco allegretto 4. Allegro Please note: this program is correct at time of printing, however it is subject to change without notice. Umberto Clerici’s performance is supported by the Embassy of Italy in Canberra, Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Sydney and Schiavello enterprise Cover photo by Sarah Walker Sarah Cover photo by 17022 SEASON 2017 ActewAGL Llewellyn Series: Cello, Horn, Violin “Music -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

PLUNGE #305 - William K

20--MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, Oct. 1.^, 1989 READ YOUR AD: ClassiFed odvertlsoments a r t I qi^ cars I CARS [g^CARS I CARS W E D ELIVER taken by telephone os o conyenlence. The FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE Manchester Herald Is responsible For only one FOR SALE For Horr>© Del: 'sry. Call Incorrect Insertion and then only tor the size oF 6 4 7 - 9 9 4 6 the original Insertion. E . rorswhichdonot lessen the yolue oF the advertisement will not be 1984 HONDA Civic Wagon CHEVROLET 1980 Ma O L D S M O B IL E 1981 R e CHEVROLET 1985 Celeb Monday to Friday. 9 to 6 - 646-0767 or 649-4554, libu - 4 door, good gency - Loaded, must rity wagon. Excellent corrected by on additional Insertion._____________ J o c k . ________ condition. $1,250. 643- sell. 643-1364.___________ condition. V-6 auto 1986 JEEP Wogoneer Li 5484. 1984 CELEBRITY-4door, matic, power steerlng- /brakes, air, cruise. CARS mited - Excellent con CHEVROLET 1974 Co Fully equipped, excel CARS CARS dition, 43,000 miles, moro - New point, new lent condition. $3,500. $4,500 or best otter. IQI i FOR SALE 647-8894. FOR SALE automatic, olr condl- vinvl top, 6 cylinder 1987 MUSTANG LX - 4 I^^H foR sale FOR SALE tlonlng, om/tm automatic, $1,750. Ne cylinder, hatchback, 5 cassette, leather Inte- gotiable. 649-8944, speed, $6,500. 646-2392. rlor. $10,900, 643-2938. leave message. TRUCKS/VANS 1984 FORD Escort Wagon C O R V E T T E 1971 S tlno STEAL It. -

Australian Composers & Sourcing Music

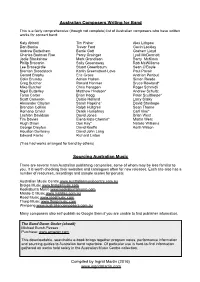

Australian Composers Writing for Band This is a fairly comprehensive (though not complete) list of Australian composers who have written works for concert band: Katy Abbott Tim Fisher Alex Lithgow Don Banks Trevor Ford Gavin Lockley Andrew Batterham Barrie Gott Graham Lloyd Charles Bodman Rae Percy Grainger Lyall McDermott Jodie Blackshaw Mark Grandison Barry McKimm Philip Bracanin Sally Greenaway Rob McWilliams Lee Bracegirdle Stuart Greenbaum Sean O’Boyle Brenton Broadstock Karlin Greenstreet-Love Paul Pavoir Gerard Brophy Eric Gross Andrian Pertout Colin Brumby Adrian Hallam Simon Reade Greg Butcher Ronald Hanmer Bruce Rowland* Mike Butcher Chris Henzgen Roger Schmidli Nigel Butterley Matthew Hindson* Andrew Schultz Taran Carter Brian Hogg Peter Sculthorpe* Scott Cameron Dulcie Holland Larry Sitsky Alexander Clayton Sarah Hopkins* David Stanhope Brendan Collins Ralph Hultgren Sean Thorne Romano Crivici Derek Humphrey Carl Vine* Lachlan Davidson David Jones Brian West Tim Davies Elena Kats-Chernin* Martin West Hugh Dixon Don Kay* Natalie Williams George Dreyfus David Keeffe Keith Wilson Houston Dunleavy David John Lang Edward Fairlie Richard Linton (*has had works arranged for band by others) Sourcing Australian Music There are several main Australian publishing companies, some of whom may be less familiar to you. It is worth checking their websites and catalogues often for new releases. Each site also has a number of resources, recordings and sample scores for perusal. Australian Music Centre www.australianmusiccentre.com.au Brolga Music www.brolgamusic.com Kookaburra Music www.kookaburramusic.com Middle C Music www.middlec.com.au Reed Music www.reedmusic.com Thorp Music www.thorpmusic.com Wirripang www.australiancomposers.com.au Many composers also self-publish so Google them if you are unable to find publisher information. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

INSIDE the MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE at 75 by John Clare*

INSIDE THE MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE AT 75 by John Clare* __________________________________________________ INSIDE THE MUSICIAN is a series of articles on the Music Trust of Australia website by music people of all kinds, revealing something about their musical worlds and how they experience them. This article appeared on June 5, 2016. To read this on that website, go to this link http://musictrust.com.au/loudmouth/inside-the-musician-john-clare-75/ o come in from a wide or oblique angle, I need to apologise briefly that my writing is not what it was. There is no excuse, but a reason of sorts. Over the T past few years I have lost a son and a sister, the wonderful old Chinese lady upstairs who died and was replaced by a crazy and nasty woman who fire bombed my flat while I was visiting my daughter in Brisbane. And more, but we’ll leave that. Perhaps this stress and distress is behind my two strokes and a triple A operation (aortic aneurism in the aorta) which comprehensively relieved me of my memory for a while. Concentration is difficult and death seems often to be hovering. Yet strangely I am very fit and can race up very steep hills on my bike or grind up on the seat. It is when I am lying down and for some time afterward that it surrounds me. We’ll leave it at that. More important than that is how music sounds and what it means in what may well be the end days. Mine anyway. Like vapour trails soaring straight up at space from the horizon, or so it seems, but finding the curvature of the earth almost directly above. -

The Collaboration of Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein

Asian Journal of Physics Vol 24, No 4 (2015) March The collaboration of Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein Estelle Asmodelle University of Central Lancashire School of Computing, Engineering and Physical Sciences, Preston, Lancashire, UK PR1 2HE. e-mail: [email protected]; Phone: +61 418 676 586. _____________________________________________________________________________________ This is a contemporary review of the involvement of Mileva Marić, Albert Einstein’s first wife, in his theoretical work between the period of 1900 to 1905. Separate biographies are outlined for both Mileva and Einstein, prior to their attendance at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zürich in 1896. Then, a combined journal is described, detailing significant events. In additional to a biographical sketch, comments by various authors are compared and contrasted concerning two narratives: firstly, the sequence of events that happened and the couple’s relationship at particular times. Secondly, the contents of letters from both Einstein and Mileva. Some interpretations of the usage of pronouns in those letters during 1899 and 1905 are re-examined, and a different hypothesis regarding the usage of those pronouns is introduced. Various papers are examined and the content of each subsequent paper is compared to the work that Mileva was performing. With a different take, this treatment further suggests that the couple continued to work together much longer than other authors have indicated. We also evaluate critics and supporters of the hypothesis that Mileva was involved in Einstein’s work, and refocus this within a historical context, in terms of women in science in the late 19th century. Finally, the definition of, collaboration (co-authorship, specifically) is outlined. -

The Spiral Dynamics of Cinema Studies Provisionally Drafted by Alex Burns ([email protected])

1 The Spiral Dynamics of Cinema Studies Provisionally Drafted by Alex Burns ([email protected]). Version 0.1 (December 1998) Comment (8th November 2007) I wrote this as a course proposal outline whilst in the Cinema Studies undergraduate program at Australia’s La Trobe University in 1998. I had been studying the Spiral Dynamics® psychological model of levels of human existence for about 18 months, and had also been corresponding with Howard Bloom and Richard Metzger. This represented a first attempt to codify the SD model using film content as examples of the models and dynamics. The artefact is from my ‘early stage’ exploration of the SD model, written with good intent but a novice’s understanding. This document has several limitations. It relied on the SD colour scheme, and prioritised breadth and span over situated depth. The selected films and sequences reflected several personal theories about media analysis and the scientific debate on memetics and were heavily influenced by the pre-millennial sub-currents of the mid- to-late 1990s. I hadn’t taken the SD practitioner training I and II at the time. My knowledge of Cinema Studies frameworks and models also varied. Thus, today I wouldn’t necessarily endorse the films or their SD codification now as correct or representative of the Beck & Cowan model or Clare W. Graves’ original research. This is provided for historical interest and self-research purposes only. I subsequently developed a more precise methodology in 2003 whilst in the Strategic Foresight masters program at Swinburne University. I trialled it in workshops at SD practitioner training and the Australian festival This Is Not Art in 2003 and 2004. -

Jill Bilcock: Dancing the Invisible

JILL BILCOCK: DANCING THE INVISIBLE PRESS KIT Written and Directed by Axel Grigor Produced by Axel Grigor and Faramarz K-Rahber Executive Produced by Sue Maslin Distributed by Film Art Media Production Company: Distributor: Faraway Productions Pty Ltd FILM ART MEDIA PO Box 1602 PO Box 1312 Carindale QLD 4152 Collingwood VIC 3066 AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Phone: +61 3 9417 2155 faraway.com.au Email: [email protected] filmartmedia.com BILLING BLOCK FILM ART MEDIA, SOUNDFIRM, SCREEN QUEENSLAND and FILM VICTORIA in association with SCREEN AUSTRALIA, THE AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION and GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY present JILL BILCOCK: DANCING THE INVISIBLE Featuring CATE BLANCHETT, BAZ LUHRMANN, SHEKHAR KAPUR and RACHEL GRIFFITHS in a FARAWAY PRODUCTIONS FILM FILM EDITORS SCOTT WALTON & AXEL GRIGOR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FARAMARZ K-RAHBER PRODUCTION MANAGER TARA WARDROP PRODUCERS AXEL GRIGOR & FARAMARZ K-RAHBER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER SUE MASLIN © 2017 Faraway Productions Pty Ltd and Soundfirm Pty Ltd. TECHNICAL INFORMATION Format DCP, Pro Res File Genre Documentary Country of Production AUSTRALIA Year of Production 2017 Running Time 78mins Ratio 16 x 9 Language ENGLISH /2 LOGLINE The extraordinary life and artistry of internationally acclaimed film editor, Jill Bilcock. SHORT SYNOPSIS A documentary about internationally renowned film editor Jill Bilcock, that charts how an outspoken arts student in 1960s Melbourne became one of the world’s most acclaimed film artists. SYNOPSIS Jill Bilcock: Dancing The Invisible focuses on the life and work of one of the world’s leading film artists, Academy award nominated film editor Jill Bilcock. Iconic Australian films Strictly Ballroom, Muriel’s Wedding, Moulin Rouge!, Red Dog, and The Dressmaker bear the unmistakable look and sensibility of Bilcock’s visual inventiveness, but it was her brave editing choices in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo+Juliet that changed the look of cinema the world over, inspiring one Hollywood critic to dub her editing style as that of a “Russian serial killer on crack”. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Young Einstein Tail Credits

(There are a number of corrections and variations between the VHS and DVD tail credits - a few are noted below). Closing titles: The End This film is dedicated to a genius, a rebel, a pacifist, an eccentric with a clowning sense of humour who once remarked about his own theories "... I never thought that others would take them so much more seriously than I did ..." Albert Einstein 1879-1955 CAST Albert Einstein Yahoo Serious Marie Curie Odile Le Clezio Preston Preston John Howard Mr. Einstein Peewee Wilson Mrs. Einstein Su Cruickshank LONELY ST. HOTEL The Blonde Lulu Pinkus The Brunette Kaarin Fairfax Manager Michael Lake BAVARIAN BREWERY Wolfgang Bavarian Jonathan Coleman Rudy Bavarian Johnny McCall PATENT OFFICE Desk Clerk Michael Blaxland Bright Clerk Ray Fogo Inventor Couple Terry & Alice Pead Nihilist Frank McDonald SYDNEY UNIVERSITY Bursar Tony Harvey Lecturer Tim Elliot Droving Student Ray Winslade Randy Student Ian 'Danno' Rogerson Prudish Student Wendy de Waal Chinese Student P. J. Voeten THE KIDS Peter Zakrzewski Sally Zakrzewski Zanzi Mann Conky Heygate Shannen de Villermont Mark Bell Dogs Albert Heygate Wombat LUNATIC ASYLUM Lunatic Professor Warren Coleman Ernest Rutherford Glenn Butcher Brian Asprin Steve Abbott Nurse Russell Cheek Gate Guard Warwick Irwin Scientists Guard Keith Heygate Cat Pie Cook Roger Ward Asylum Guard Ted Reid Crazed Lunatic Martin Raphael Dangerous Lunatics The Film Crew CURIE ESTATE Mr. Curie Max Meldrum Mrs. Curie Rose Jackson SCIENCE ACADEMY AWARDS Charles Darwin Basil Clarke Marconi Adam Bowen Wilbur -

Only the Dead

SCREEN AUSTRALIA PRESENTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION ONLY THE DEAD PRODUCTION NOTES Running time: 77:11 ONLY THE DEAD Directed by BILL GUTTENTAG and MICHAEL WARE Written by MICHAEL WARE Produced by PATRICK MCDONALD Produced by MICHAEL WARE Executive Producer JUSTINE A. ROSENTHAL Editor JANE MORAN Music by MICHAEL YEZERSKI Associate Producer ANDREW MACDONALD • SCREEN AUSTRALIA /PRESENTS A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL ONLY THE DEAD One Line Synopsis What happens when one of the most feared, most hated terrorists on the planet chooses you—personally—to reveal his arrival on the global stage? All in the midst of the American war in Iraq? Short Synopsis Theatrical feature documentary Only the Dead is the story of what happens when one ordinary man, an Australian journalist transplanted into the Middle East by the reverberations of 9/11, butts into history. It is a journey that courses through the deepest recesses of the Iraq war, revealing a darkness lurking in his own heart. A darkness that he never knew was there. The invasion of Iraq has ended, and the Americans are celebrating victory. The year is 2003. The international press corps revel in the Baghdad “Summer of Love”, there is barely a spare hotel room in the entire city. Reporters of all nationalities scramble for stories; of the abuses of Saddam’s fallen regime; of WMD’s, of reconstruction, of liberation. There are pool parties, and restaurant outings, and dinner-party circuits. Occasionally, Coalition forces are attacked, but always elsewhere, somewhere in the background.