Strawberry Insect Scouting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Landscape Ecology to Improve Strawberry Sap Beetle

Applying Landscape The lack of effective con- trol measures for straw- Ecology to Improve berry sap beetle is a problem at many farms. Strawberry Sap Beetle The beetles appear in strawberry fi elds as the Management berries ripen. The adult beetle feeds on the un- Rebecca Loughner and Gregory Loeb derside of berries creat- Department of Entomology ing holes, and the larvae Cornell University, NYSAES, Geneva, NY contaminate harvestable he strawberry sap beetle (SSB), fi eld sanitation, and renovating promptly fruit leading to consumer Stelidota geminata, is a significant after harvest. Keeping fi elds suffi ciently complaints and the need T insect pest in strawberry in much of clean of ripe and overripe fruit is nearly the Northeast. The small, brown adults impossible, especially for U-pick op- to prematurely close (Figure 1) are approximately 1/16 inch in erations, and the effectiveness of the two length and appear in strawberry fi elds as labeled pyrethroids in the fi eld is highly fi elds at great cost to the the berries ripen. The adult beetle feeds variable. Both Brigade [bifenthrin] and grower. Our research has on the underside of berries creating holes. Danitol [fenpropathrin] have not provided Beetles prefer to feed on over-ripe fruit but suffi cient control in New York and since shown that the beetles do will also damage marketable berries. Of they are broad spectrum insecticides they not overwinter in straw- more signifi cant concern, larvae contami- can potentially disrupt predatory mite nate harvestable fruit leading to consumer populations that provide spider mite con- berry fi elds. -

Coleoptera: Nitidulidae, Kateretidae)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida March 2006 An annotated checklist of Wisconsin sap and short-winged flower beetles (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae, Kateretidae) Michele B. Price University of Wisconsin-Madison Daniel K. Young University of Wisconsin-Madison Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Price, Michele B. and Young, Daniel K., "An annotated checklist of Wisconsin sap and short-winged flower beetles (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae, Kateretidae)" (2006). Insecta Mundi. 109. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/109 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 1-2, March-June, 2006 69 An annotated checklist of Wisconsin sap and short-winged flower beetles (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae, Kateretidae) Michele B. Price and Daniel K. Young Department of Entomology 445 Russell Labs University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, WI 53706 Abstract: A survey of Wisconsin Nitidulidae and Kateretidae yielded 78 species through analysis of literature records, museum and private collections, and three years of field research (2000-2002). Twenty-seven species (35% of the Wisconsin fauna) represent new state records, having never been previously recorded from the state. Wisconsin distribution, along with relevant collecting techniques and natural history information, are summarized. The Wisconsin nitidulid and kateretid faunae are compared to reconstructed and updated faunal lists for Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and south-central Canada. -

Profile Infestation with the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina Tumida)

Infestation with the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina tumida) Susceptible species The small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) is a pest of honey bees (Apis mellifera). In its larval stage the small hive beetle feeds on brood, pollen and honey and can thus damage the bee colony. Bumblebees and stingless bees can serve as alternative hosts; for solitary bees this is still unclear. The beetle does not represent a human health risk. Distribution area Originally, the small hive beetle occurs in Africa, south of the Sahara. By worldwide trade with honey bees, the beetle was introduced to America and Australia around the turn of the millenium, where it spread rapidly over large areas. Meanwhile, it has been reported at least once on all continents except the Antarctic. In spite of EU-wide import restrictions, Aethina tumida was detected in Calabria, Southern Italy, in September 2014; all attempts to eradicate have been unsuccessful. Causative agent The dark-brown to black small hive beetle belongs to the family of sap beetles (Nitidulidae). The adult beetle has about a third of the size of a honey bee (approx. 5mm long, 3mm wide). Fertilized females lay eggs in crevices inside the hive; they may also bite holes into cell cappings and walls to lay their eggs directly into the brood cells. The white to beige larvae emerge after one to three days. After another ten to fourteen days they reach the so-called wandering stage (approx. 10 mm long), leave the hive, and pupate in the soil. At warm summer temperatures the new generation emerges approx. -

Biology of Dried Fruit Beetle, Carpophilus Hemipterus (L) and Its Damage Assessment on Different Dried Fruits in Storage

BIOLOGY OF DRIED FRUIT BEETLE, CARPOPHILUS HEMIPTERUS (L) AND ITS DAMAGE ASSESSMENT ON DIFFERENT DRIED FRUITS IN STORAGE MST. REZENNAHAR KUMKUM DEPARTMENT OF ENTOMOLOGY SHER-E-BANGLA AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY DHAKA-1207 JUNE, 2017 1 BIOLOGY OF DRIED FRUIT BEETLE, CARPOPHILUS HEMIPTERUS (L) AND ITS DAMAGE ASSESSMENT ON DIFFERENT DRIED FRUITS IN STORAGE BY MST. REZENNAHAR KUMKUM REG. NO.: 11-04566 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Agriculture Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE (MS) IN ENTOMOLOGY SEMESTER: JANUARY - JUNE, 2017 APPROVED BY: ………………………………………………….. …………………………………………… (Prof. Dr. Mohammed Ali) (Prof. Dr. Tahmina Akter) Supervisor Co-Supervisor Department of Entomology Department of Entomology SAU, Dhaka -1207 SAU, Dhaka-1207 ………………………………………………….. Dr. Mst. Nur Mahal Akter Banu Chairman Department of Entomology & Examination Committee 2 DEPARTMENT OF ENTOMOLOGY Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Biology of dried fruit beetle, Carpophilus hemipterus (L) and its damage assessment on different dried fruits in storage’ submitted to the Faculty of Agriculture, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology embodies the result of a piece of bona fide research work carried out by Mst. Rezennahar Kumkum, Registration number: 11-04566 under my supervision and guidance. No part of the thesis has been submitted for any other degree or diploma. I further certify that any help or source of information, received during the course of this investigation has duly been acknowledged. -

Species Common Name (Scientific Name) New Rare 1 Bees, Wasps

The species collected in your Malaise trap are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. ‘New’ refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in your trap out of all 81 that were deployed for the program. Species # Group (scientific name) Species common name (scientific name) New Rare 1 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Small carpenter bee (Ceratina) b 2 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Cuckoo bee (Nomada bella) b 3 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Cuckoo bee (Nomada subrutila) b 4 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Braconid parasitic wasp (Braconidae) 5 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Braconid parasitic wasp (Aphidius rhopalosiphi) 6 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Braconid parasitic wasp (Aphidius rhopalosiphi) b 7 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Wood ant (Formica) 8 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Winter ant (Prenolepis imparis) b 9 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Odorous house ant (Tapinoma sessile) b b 10 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Ichneumon wasp (Ichneumonidae) 11 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Ichneumon wasp (Lissonota sexcincta recurvariae) 12 Bees, wasps & ants (Hymenoptera) Platygastrid parasitic wasp (Platygastridae) b 13 Beetles (Coleoptera) Antlike flower beetle (Anthicidae) 14 Beetles (Coleoptera) Ground beetle (Agonum melanarium) 15 Beetles (Coleoptera) Grape flea beetle (Altica chalybea) 16 Beetles (Coleoptera) Leaf beetle (Altica corni) 17 Beetles (Coleoptera) Leaf beetle (Crepidodera -

New Invasive Species of Nitidulidae (Coleoptera)

Epuraea imperialis (Reitter, 1877). New invasive species of Nitidulidae (Coleoptera) in Europe, with a checklist of sap beetles introduced to Europe and Mediterranean areas Josef Jelinek, Paolo Audisio, Jiri Hajek, Cosimo Baviera, Bernard Moncourtier, Thomas Barnouin, Hervé Brustel, Hanife Genç, Richard A. B. Leschen To cite this version: Josef Jelinek, Paolo Audisio, Jiri Hajek, Cosimo Baviera, Bernard Moncourtier, et al.. Epuraea imperialis (Reitter, 1877). New invasive species of Nitidulidae (Coleoptera) in Europe, with a checklist of sap beetles introduced to Europe and Mediterranean areas. AAPP | Physical, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, Accademia Peloritana dei Pericolanti, 2016, 94 (2), pp.1-24. 10.1478/AAPP.942A4. hal-01556748 HAL Id: hal-01556748 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01556748 Submitted on 5 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Open Archive TOULOUSE Archive Ouverte (OATAO) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible. This is a publisher-deposited version published in : http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID : 17782 To link to this article : DOI :10.1478/AAPP.942A4 URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.1478/AAPP.942A4 To cite this version : Jelinek, Josef and Audisio, Paolo and Hajek, Jiri and Baviera, Cosimo and Moncourtier, Bernard and Barnouin, Thomas and Brustel, Hervé and Genç, Hanife and Leschen, Richard A. -

Stored Product Pests Department of Entomology

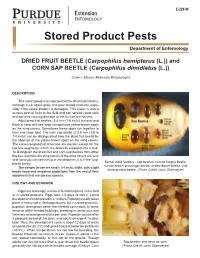

E-229-W Stored Product Pests Department of Entomology DRIED FRUIT BEETLE (Carpophilus hemipterus (L.)) and CORN SAP BEETLE (Carpophilus dimidiatus (L.)) Linda J. Mason, Extension Entomologist DESCRIPTION This insect group is a major pest of the dried fruit industry, although it will attack grain and grain based products, espe- cially if the cereal product is damaged. This insect is also a serious pest of fruits in the field and can spread yeast cells and bacteria causing damage to the fruit before harvest. Adult dried fruit beetles (3-4 mm (1/8 inch)) are oval and black in color with two large conspicuous yellow-brown spots on the wing covers. Sometimes these spots run together to form one large spot. The corn sap beetle (2-3.5 mm (1/8 to 1/4 inch)) can be distinguished from the dried fruit beetle by the absence of the yellow-brown spots on the wing covers. The eleven segmented antennae are slender except for the last few segments, which are distinctly enlarged into a club. To distinguish the dried fruit and corn sap beetles from other beetles, examine the wing covers. If the wing covers are very short and you can see the tip of the abdomen, it is in the “sap” Kernel mold feeders - sap beetles, minute fungus beetle, beetle family. minute brown scavenger beetle, antlike flower beetle, and The slender larvae are small (1/4 inch), white, with a light shining mold beetle. (Photo Credit: John Obermeyer) brown head and hardened projections from the end of their abdomens that are species specific. -

A Scientific Note on Rapid Host Shift of the Invasive Dusky Sap Beetle

A scientific note on rapid host shift of the invasive dusky sap beetle (Carpophilus lugubris) in Italian beehives: new commensal or potential threat for European apiculture? Paolo Audisio, Francesca Marini, Enzo Gatti, Fabrizio Montarsi, Franco Mutinelli, Alessandro Campanaro, Andrew Cline To cite this version: Paolo Audisio, Francesca Marini, Enzo Gatti, Fabrizio Montarsi, Franco Mutinelli, et al.. A scientific note on rapid host shift of the invasive dusky sap beetle (Carpophilus lugubris) in Italian beehives: new commensal or potential threat for European apiculture?. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2014, 45 (4), pp.464-466. 10.1007/s13592-013-0260-3. hal-01234739 HAL Id: hal-01234739 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234739 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:464–466 Scientific note * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2013 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-013-0260-3 A scientific note on rapid host shift of the invasive dusky sap beetle (Carpophilus lugubris) in Italian beehives: new commensal or potential threat for European apiculture? 1 1,2 3 4 4 Paolo AUDISIO , Francesca MARINI , Enzo GATTI , Fabrizio MONTARSI , Franco MUTINELLI , 1 5 Alessandro CAMPANARO , Andrew Richard CLINE 1Department of Biology and Biotechnologies “C. -

SMALL HIVE BEETLE Authored by Morgan A. Roth, Aaron D. Gross

SMALL HIVE BEETLE Authored by Morgan A. Roth, Aaron D. Gross, and James M. Wilson Department of Entomology, Virginia Tech Order: Coleoptera Family: Nitidulidae Species: Aethina tumida (Murray) Over the past 20 years, small hive beetles have been spreading across the United States, infesting hives and evading control attempts. Since the discovery of small hive beetle in central Florida in 1998, these beetles from sub-Saharan Africa have travelled to almost every state in the US and arrived in Virginia by 2004. Although small hive beetles are not as economically significant as Varroa mites, they were estimated to have caused around $3 million dollars in damage each year in the United States by 2004. As the geographic range has continued to expand, it is likely that the economic impact from small hive beetles has increased as well. The large geographic range and significant damage caused by these pests warrants greater awareness and insight into small hive beetle management. This fact sheet will provide details about small hive beetle biology, which is a crucial part of identification and treatment, along with popular small hive beetle control methods. BIOLOGY AND DESCRIPTION: Adult small hive beetles are 5-7 mm (approximately ¼ inch) long and 3-4.5 mm wide. Adult beetles are brown in color, which darkens to black over time (Figure 1). Small hive beetles are also strong fliers, which is how they travel to hives. Although small hive beetles belong to the sap beetle family and can live outside of honey bee colonies, these scavenging beetles will seek out colonies, likely for the protection and easy access to food that colonies offer. -

Beetles) of the Sandwell Valley

A checklist of the Coleoptera (Beetles) Of the Sandwell Valley M.G.Bloxham August 2019 1 Summary 1095 Beetle Records 59 families 535 species 2 A provisional List of Sandwell Valley Beetles The list is the product of some 40 years of recording in the 20 one Km SP squares shown on the map. Records have not been gathered in any systematic way, but are the product of numerous visits to the area by individuals and field meetings when SANDNATS members carried out general recording events. A reference collection of nearly all the beetles discovered is held by Mike Bloxham. A few specimens are held by other entomologists. Mr Paul Edwards has a small unit of rove beetles and the late Mr Eric Brown (Coleoptera Recorder for Staffordshire) who checked nearly all the weevils and some beetles from other families, retained a few specimens for his collection. These are now located in The British Museum of Natural History (South Kensington). The collection probably reflects the ecology of the Sandwell Valley with its characteristic and varied mosaic of habitats reasonably well. It is also to some extent indicative of its history. A number of species included in the Index of Ecological Continuity and Saproxylic Quality index (marked in yellow in the lists) have been discovered in the fragmented woodlands on the old estate of the Earl of Dartmouth, with remnants of its surrounding deer park. These are probably survivors from a rather richer fauna that existed before the industrial revolution began to transform the area and the estate fell into disrepair. -

Amberif 2018

AMBERIF 2018 Jewellery and Gemstones INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM AMBER. SCIENCE AND ART Abstracts 22-23 MARCH 2018 AMBERIF 2018 International Fair of Ambe r, Jewellery and Gemstones INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM AMBER. SCIENCE AND ART Abstracts Editors: Ewa Wagner-Wysiecka · Jacek Szwedo · Elżbieta Sontag Anna Sobecka · Janusz Czebreszuk · Mateusz Cwaliński This International Symposium was organised to celebrate the 25th Anniversary of the AMBERIF International Fair of Amber, Jewellery and Gemstones and the 20th Anniversary of the Museum of Amber Inclusions at the University of Gdansk GDAŃSK, POLAND 22-23 MARCH 2018 ORGANISERS Gdańsk International Fair Co., Gdańsk, Poland Gdańsk University of Technology, Faculty of Chemistry, Gdańsk, Poland University of Gdańsk, Faculty of Biology, Laboratory of Evolutionary Entomology and Museum of Amber Inclusions, Gdańsk, Poland University of Gdańsk, Faculty of History, Gdańsk, Poland Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Institute of Archaeology, Poznań, Poland International Amber Association, Gdańsk, Poland INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Dr Faya Causey, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA Prof. Mitja Guštin, Institute for Mediterranean Heritage, University of Primorska, Slovenia Prof. Sarjit Kaur, Amber Research Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY, USA Dr Rachel King, Curator of the Burrell Collection, Glasgow Museums, National Museums Scotland, UK Prof. Barbara Kosmowska-Ceranowicz, Museum of the Earth in Warsaw, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland Prof. Joseph B. Lambert, Department of Chemistry, Trinity University, San Antonio, TX, USA Prof. Vincent Perrichot, Géosciences, Université de Rennes 1, France Prof. Bo Wang, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Prof. Barbara Kosmowska-Ceranowicz – Honorary Chair Dr hab. inż. Ewa Wagner-Wysiecka – Scientific Director of Symposium Prof. -

Identification of the Small Hive Beetle Aethina Tumida, Morphological Examination (OIE Method)

WORK INSTRUCTION _ SOPHIA ANTIPOLIS LABORATORY Identification of the small hive beetle Aethina tumida, morphological examination (OIE method) Coding: ANA-I1.MOA.1500 Revision: 01 Page 1 / 12 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE ....................................................................................................................................2 2. CONTENT........................................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Principle ...................................................................................................................................................3 2.2 Materials ..................................................................................................................................................3 2.3 Protocol....................................................................................................................................................3 2.4 Identification of the small hive beetle A. tumida ....................................................................................5 3. ANALYTICAL RESULTS...................................................................................................................................12 3.1 Adult forms ............................................................................................................................................12 3.2 Larval forms............................................................................................................................................12