The Enigma of the Mason Hymn-Tunes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

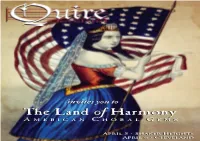

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

JOHN Wesley's “DIRECTIONS for SINGING”

Methodist History, 47:4 (July 2009) JOHN WESLEy’S “DIRECTIONS FOR SINGING”: METHODIST HYMNODY AS AN EXPRESSION OF METHODIST BELIEFS IN THOUGHT AND PRACTICE MARTIN V. CLARKE John Wesley’s “Directions for Singing” was included as an appendage to Select Hymns: with Tunes Annext (1761), a collection of hymn texts and tunes designed for congregational use across the Methodist Connexion.1 Although a list of only seven brief points, it reveals much about the way in which Wesley desired music to be used in Methodist worship and the ben- efits that he believed could be reaped from its effective use. Carlton Young suggests that the “Directions” represent “Wesley’s attempts to standardize hymn singing performance and repertory,”2 which is borne out by their pub- lication together with the tunes of Select Hymns, which Wesley advocated as authentically Methodist. The full significance of these instructions can only be understood when they are considered in relation to the theological and doctrinal position of Methodism, while they need to be assessed alongside Select Hymns and other collections of tunes used within Methodism in order to evaluate their impact. They highlight the importance Wesley attached to Select Hymns, while also offering more general practical advice, before con- cluding with a reminder of the purpose of congregational singing: That this part of Divine Worship may be the more acceptable to God, as well as the more profitable to yourself and others, be careful to observe the following direc- tions. I. Learn these Tunes before you learn any others; afterwards learn as many as you please. -

Appendix to the Elements of Vocal Music, Containing Exercises for Practice

PUBLIC LIBRARY OF CINCINNATI AND HAMILTON COUNTY Aulhoriied in 1853 as a Public and School Library, it became in 1867 an independent Public Library for the city, and in 1898 the Library for all of Hamilton County. Departmenu in the central building,branch librariea, lUtiont and bookmobile* provide a lending and reference lervice of literary, educational and recreational nulenal for aU. TTu Futlit Library u Yours . Vu it! Form No. 00101 RECOMMENDATIONS. lfIA80]\lS' 8ACRED HARP, or Beauties ot Church IVIuisic, is adapted to the wants of all denominations. The variety of metres is very great, and but few Hymns are contained in the Hymn Books of the different christian worshippers, for which a tune may not be found in this collection; It will be found to contain a great variety of Psalm and Hymn tunes; also a collection of interesting Anthems, Set Pieces, Sacred Songs, Sentences and Chants, which are short, easy of performance without instrumental aid, and appropriate to the various occasions of public worship, the wanta of singing schools, musical societies, and pleasing and useful to singers for their own private practice and improvement. MASONS' various collections have all been preeminently popular and useful in the estimation of men of science and taste, both in Europe and America. The Sacred Harp is the authors' last production, and it is not excelled by any other collection. Teachers of singing, clergymen and others who are desirous of promoting Sacred Music, can employ no means so effectual as the circulation of this valuable work. From the JVew York Evangelist: edited by J, Leavitt, author of the Christian Li/re, a From Mr. -

Three Preludes on Hymn Tunes John G

Bridgewater College BC Digital Commons Music Faculty Scholarship Department of Music 1992 Three Preludes on Hymn Tunes John G. Barr Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bridgewater.edu/ music_faulty_scholarship Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Barr, John G. Three Preludes on Hymn Tunes. FL: H.W. Gray Publications, c/o CPP/Belwin, Inc., 1992. This Sheet Music is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Music at BC Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BC Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~- ·---- - - · - -- - ---- - --- ------ --- ~------ ---- ·~aiut Qlrrilia~rrirs ®rg.an <fotttpn.attiott.a THREE PRELUDES ON HYMN TUNES (AURELIA, MELITA AND CWM RHONDDA) by JOHNG.BARR ~nint Qlrrili ®rgnu Qlnmpnnir THREE PRELUDES ON HYM (AURELIA, MELITA. AND CWM RHONDDA) by JOHNG.BARR Copyright© 1992 H.W. Gray Publications, c/o CPP/Belwin, Inc., Miami, FL. 33014 International Copyright Secured Made in U.S.A. All Rights Reserved 2 for Mrs. Lois Wine PRELUDE ON "AURELIA"* (The Church's One Foundation) SW: Principal Chorus GT: Principal Chorus PED: Bourdons 16', 8', Sw. to Ped. JOHNG.BARR Sw. ~ f\ I -.., -1 I ,,, I IF, I - I I I J. h I llflll f.lllli. 1111111 .... I ... --, I r r I I I I - v - Ir "\-.a IF 'J !""' ,_ !""' .... .... I I I . I I I .-1 I 1111111 1111111 I- I .... ..... Ill/I/fl ..... .-1 I .-1 I I I .-1 I 'Jilli! 1111111 - ' \J - - - HJ I - - • - - - • .__ v=== ...=.,.- ...... - ....- - - mp --- r 111111" r - L ,. -

School Ofmusic

University of Washington 1998-1999 School ofMusic ~ 13, f£"'9 presents CD I ?, 4(p 0 I< 6~ ( 'if If THE LITTLEFIELD ORGAN SERIES '1-1.,) i with guest artist DAVID ROTHE April 23, 1999 12:30 PM and 8:00 PM Walker-Ames Room PROGRAM CD ill Prelude and Fugue in C Minor (5'30 (BWV 549, Arnstadt 1703) .... " ......"' ... ~..... ~.t ................ Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) o Settings from orgelb.uchlein (Weimar, c. 1717) ...... ~.............................................J. S. Bach o Mensch bewein dein Sunde gross (BWV 622) 4-: 'to) Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt (BWV 637) ,',If0) ~ Two shorr settings of "Christ ist erstanden" .{t.:}~)......... Buxheimer Orgelbuch (c. 1470) ttl Nun bittenwir den Heiligen Geist (BuxWV 2078)~:~.~)Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) rn Praeludium in e minor (The Greater) .... .c.2'JQ.~.) ..................Nicolaus Bruhns (1665-1697) [kl Englische Nachtigal (Celler Clavierbuch, 1662).. C.!.~.Y.C?L .......Anonymous, 17th C. German [jJ From the Eighteen Great Chorales (Leipzig, 1747-49) ..~L::?2 ............................]. S. Bach Komm, Gott Schopfer, heiliger Geist (BWV 667) 00 Prelude and fugue in C Major (BWV 547, Leipzig, 1744) ... J¥.;.%.)....................]. S. Bach Ci1 6V\ tcrfe:. - (2- ~2-2) ----~~- The first piece. on today's .program, t~e Prelude an,d mostly anonymous composers,~nd is written in .. new" Fugue in C Mmor, was wntte~ early In J. S. B~ch s German organ tablature. The pieces are mostly dances, career, perhaps while he was std! a tee!lager., This set songs, arias. hymns, chorales and variation cycles which (sometimes called 'the Arnstadt) begms with a bold were probably used for entertainment, dancing and pedal cadenza, reminiscent of the works of Georg B6hm devotional services at the court of CelIe. -

Luther's Hymn Melodies

Luther’s Hymn Melodies Style and form for a Royal Priesthood James L. Brauer Concordia Seminary Press Copyright © 2016 James L. Brauer Permission granted for individual and congregational use. Any other distribution, recirculation, or republication requires written permission. CONTENTS Preface 1 Luther and Hymnody 3 Luther’s Compositions 5 Musical Training 10 A Motet 15 Hymn Tunes 17 Models of Hymnody 35 Conclusion 42 Bibliography 47 Tables Table 1 Luther’s Hymns: A List 8 Table 2 Tunes by Luther 11 Table 3 Tune Samples from Luther 16 Table 4 Variety in Luther’s Tunes 37 Luther’s Hymn Melodies Preface This study began in 1983 as an illustrated lecture for the 500th anniversary of Luther’s birth and was presented four times (in Bronxville and Yonkers, New York and in Northhampton and Springfield, Massachusetts). In1987 further research was done on the question of tune authorship and musical style; the material was revised several times in the years that followed. As the 500th anniversary of the Reformation approached, it was brought into its present form. An unexpected insight came from examining the tunes associated with the Luther’s hymn texts: Luther employed several types (styles) of melody. Viewed from later centuries it is easy to lump all his hymn tunes in one category and label them “medieval” hymns. Over the centuries scholars have studied many questions about each melody, especially its origin: did it derive from an existing Gregorian melody or from a preexisting hymn tune or folk song? In studying Luther’s tunes it became clear that he chose melody structures and styles associated with different music-making occasions and groups in society. -

Hymn Tune Hymn Tune Common Title 1 Aberystwyth Savior

TO DIAL A HYMN NUMBER: While pressing the HYMN PLAYER piston, press General pistons. (Zero is piston #10). Press PLAY. After the intro and each verse press PLAY. (PEDALS ARE DISABLED DURING HYMN PLAYING). TO PLAY A CONTINUOUS PRELUDE: Rotate the SELECT knob to MODE. Select General or Christmas. Press PLAY for continuous play. HYMN TUNE HYMN TUNE COMMON TITLE 1 ABERYSTWYTH SAVIOR, WHEN IN DUST TO YOU (THEE) 2 ACK, VAD AR DOCK LIVET HAR JESUS, IN THY DYING WOES 3 ADELAIDE HAVE THINE OWN WAY 4 ADESTES FIDELES O COME, ALL YE FAITHFUL 5 ALL IS WELL IT IS WELL WITH MY SOUL 5 ALL IS WELL WHEN PEACE LIKE A RIVER 6 ALL THE WAY ALL THE WAY MY SAVIOR LEADS ME 7 ALL TO CHRIST ALL TO CHRIST 8 AMERICA GOD BLESS OUR NATIVE LAND 9 AMSTERDAM OPEN LORD MY INWARD EAR 9 AMSTERDAM PRAISE THE LORD WHO REIGNS ABOVE 9 AMSTERDAM RISE, MY SOUL, AND STRETCH THY WINGS 10 ANGEL'S STORY ANGEL'S STORY 11 ANGELIC SONGS ANGELIC SONGS 12 ANTIOCH JOY TO THE WORLD 13 AR HYD Y NOS FOR THE FRUITS OF ALL CREATION 13 AR HYD Y NOS DAY IS DONE 13 AR HYD Y NOS GO, MY CHILDREN, WITH MY BLESSING 13 AR HYD Y NOS GOD, WHO MADE THE EARTH AND HEAVEN 14 ARLINGTON I'M NOT ASHAMED TO OWN MY LORD 15 ASCEND TO ZION'S ASCEND TO ZION'S HIGHEST 16 ASH GROVE SENT FORTH BY GOD'S BLESSING 16 ASH GROVE LET ALL THINGS NOW LIVING 17 ASSAM I HAVE DECIDED TO FOLLOW JESUS 18 ASSURANCE BLESSED ASSURANCE 19 AURELIA O FATHER, ALL CREATING 19 AURELIA O LIVING BREAD FROM HEAVEN 19 AURELIA THE CHURCH'S ONE FOUNDATION 20 AUSTRIAN HYMN GLORIOUS THINGS OF YOU ARE SPOKEN 20 AUSTRIAN HYMN PRAISE THE LORD! O HEAVENS -

The Supplemental Hymn and Tune Book

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 4. A 2 a.... _T fºLº F O U R T H E D IT IO N. THE * | º Ü Ü | i -> supplemental jumum ſult `-- (WITH NEW APPENDIX). Under the sanction of the Lord Bishop of Worcester. EDITED BY THE frves, *. * REV. ROBERT BROWN-Bon THwick. LONDON: NOVELLO, EWER AND CO. OXFORD: W. R. BowdEN; Evesham w. AND H. SMITH, (A ſmall Edition of the Word, alone, fºr Congregational use, neatly bound in cloth, price Sixpence.) “On earth join all ye creatures to extol “Him firſt, Him laſt, Him midſt, and without end.” TO H E R R O Y A L H I G H N E S S W I C T O R I A, PRINCESS IMPERIAL OF GERMANY., PRINCESS ROYAL OF ENGLAND, THIS BOOK IS (BY SPECIAL PERMISSION) DEDICATED WITH ALL RESPECT, BY H E R R O Y A L H IG H N ESS'S MOST OBEDIENT HUMBLE SERVANT, ROBERT BROWN- BORT H WICK. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. “The Supplemental Hymn and Tune Book” was at first intended to be a collection of about five-and-twenty Hymns and original Tunes in the form of a pamphlet, to enable a comparatively limited circle of the Com piler's friends and others to obtain copies of those which, from their popu larity wherever they were introduced, involved, owing to the frequency of application for them, no slight labour in copying. -

Tifh CHORALE CANTATAS

BACH'S TREATMIET OF TBE CHORALi IN TIfh CHORALE CANTATAS ThSIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Floyd Henry quist, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1950 N. T. S. C. LIBRARY CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. ...... .... v PIEFACE . vii Chapter I. ITRODUCTION..............1 II. TECHURCH CANTATA.............T S Origin of the Cantata The Cantata in Germany Heinrich Sch-Utz Other Early German Composers Bach and the Chorale Cantata The Cantata in the Worship Service III. TEEHE CHORAI.E . * , . * * . , . , *. * * ,.., 19 Origin and Evolution The Reformation, Confessional and Pietistic Periods of German Hymnody Reformation and its Influence In the Church In Musical Composition IV. TREATENT OF THED J1SIC OF THE CHORAIJS . * 44 Bach's Aesthetics and Philosophy Bach's Musical Language and Pictorialism V. TYPES OF CHORAJETREATENT. 66 Chorale Fantasia Simple Chorale Embellished Chorale Extended Chorale Unison Chorale Aria Chorale Dialogue Chorale iii CONTENTS (Cont. ) Chapter Page VI. TREATMENT OF THE WORDS OF ThE CHORALES . 103 Introduction Treatment of the Texts in the Chorale Cantatas CONCLUSION . .. ................ 142 APPENDICES * . .143 Alphabetical List of the Chorale Cantatas Numerical List of the Chorale Cantatas Bach Cantatas According to the Liturgical Year A Chronological Outline of Chorale Sources The Magnificat Recorded Chorale Cantatas BIBLIOGRAPHY . 161 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIO1S Figure Page 1. Illustration of the wave motive from Cantata No. 10e # * * # s * a * # . 0 . 0 . 53 2. Illustration of the angel motive in Cantata No. 122, - - . 55 3. Illustration of the motive of beating wings, from Cantata No. -

Reshaping American Music: the Quotation of Shape-Note Hymns by Twentieth-Century Composers

RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS by Joanna Ruth Smolko B.A. Music, Covenant College, 2000 M.M. Music Theory & Composition, University of Georgia, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Faculty of Arts and Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Historical Musicology University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Joanna Ruth Smolko It was defended on March 27, 2009 and approved by James P. Cassaro, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Music Mary S. Lewis, Professor, Department of Music Alan Shockley, Assistant Professor, Cole Conservatory of Music Philip E. Smith, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Deane L. Root, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Joanna Ruth Smolko 2009 iii RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS Joanna Ruth Smolko, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Throughout the twentieth century, American composers have quoted nineteenth-century shape- note hymns in their concert works, including instrumental and vocal works and film scores. When referenced in other works the hymns become lenses into the shifting web of American musical and national identity. This study reveals these complex interactions using cultural and musical analyses of six compositions from the 1930s to the present as case studies. The works presented are Virgil Thomson’s film score to The River (1937), Aaron Copland’s arrangement of “Zion’s Walls” (1952), Samuel Jones’s symphonic poem Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1974), Alice Parker’s opera Singers Glen (1978), William Duckworth’s choral work Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1980-81), and the score compiled by T Bone Burnett for the film Cold Mountain (2003). -

A Transformational Method for Chorale Generation

A Transformational Method for Chorale Generation Raymond Whorley1 and Darrell Conklin1,2 1 Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, San Sebasti´an, Spain 2 IKERBASQUE, Basque Foundation for Science, Bilbao, Spain [email protected],[email protected] Abstract. Music sampled from a statistical model tends to lack long- term structure. This problem can be ameliorated by transforming an existing piece of music into a new one, such that the structure of the original is retained. A method for transforming Bach chorales is pre- sented here. Sampling is constrained by chord symbols, phrase boundary information, soprano note lengths and key regions from the original mu- sic. Two corpora are used: one of hymn tune harmonisations by various composers, and the other of chorale melody harmonisations by J. S. Bach. 1 Introduction A problem with Markov models for music generation is that music sampled from a model tends to lack long-term structure; that is, the output can seem to wander due to the limited context used. The solution proposed here is to transform an existing piece of music such that the new piece is related to the original in some abstract way. To generate a well-structured four-part harmonic texture, hopefully including a coherent and novel melody, a structural template is created from a chorale melody harmonisation by J. S. Bach. Multiple pieces are then generated in line with the template with the aim of finding low cross- entropy (negative mean log probability) solutions, as these tend to be in better compliance with generally agreed rules of harmony [1]. -

Instrumental - Copy

instrumental - Copy All Library Opus Score Parts Publishe Number Title # Composer Arranger Larger Work Instrumentation Y/N? Y/N? r Notes *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001 500 Hymns for Instruments* Lane, Harold Instruments Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-001 How Firm a Foundation Early American Melody Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the Joyful, Joyful, We Adore 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-002 Thee Beethoven, Ludwig van Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-003 To God Be the Glory Doane, W. H. Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the A Mighty Fortress Is Our 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-004 God Luther, Martin Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-005 How Great Thou Art! Swedish Folk Melody Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-006 O Worship the King Haydn, Johann Michael Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-007 Majestic Sweetness Hastings, Thomas Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-008 Almighty Dykes, John B.