Addictive Disorders in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

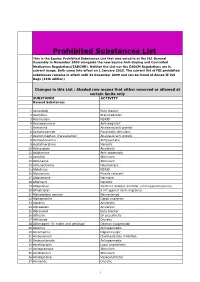

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Forensic Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Exactive Plus High-Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Forensic Toxicology use Only Drugs analyzed Compound Compound Compound Atazanavir Efavirenz Pyrilamine Chlorpropamide Haloperidol Tolbutamide 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)piperazine Des(2-hydroxyethyl)opipramol Pentazocine Atenolol EMDP Quinidine Chlorprothixene Hydrocodone Tramadol 10-hydroxycarbazepine Desalkylflurazepam Perimetazine Atropine Ephedrine Quinine Cilazapril Hydromorphone Trazodone 5-(p-Methylphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin Desipramine Phenacetin Benperidol Escitalopram Quinupramine Cinchonine Hydroquinine Triazolam 6-Acetylcodeine Desmethylcitalopram Phenazone Benzoylecgonine Esmolol Ranitidine Cinnarizine Hydroxychloroquine Trifluoperazine Bepridil Estazolam Reserpine 6-Monoacetylmorphine Desmethylcitalopram Phencyclidine Cisapride HydroxyItraconazole Trifluperidol Betaxolol Ethyl Loflazepate Risperidone 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline Desmethylclozapine Phenylbutazone Clenbuterol Hydroxyzine Triflupromazine Bezafibrate Ethylamphetamine Ritonavir 7-Aminoclonazepam Desmethyldoxepin Pholcodine Clobazam Ibogaine Trihexyphenidyl Biperiden Etifoxine Ropivacaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Desmethylmirtazapine Pimozide Clofibrate Imatinib Trimeprazine Bisoprolol Etodolac Rufinamide 9-hydroxy-risperidone Desmethylnefopam Pindolol Clomethiazole Imipramine Trimetazidine Bromazepam Felbamate Secobarbital Clomipramine Indalpine Trimethoprim Acepromazine Desmethyltramadol Pipamperone -

Appendix-2Final.Pdf 663.7 KB

North West ‘Through the Gate Substance Misuse Services’ Drug Testing Project Appendix 2 – Analytical methodologies Overview Urine samples were analysed using three methodologies. The first methodology (General Screen) was designed to cover a wide range of analytes (drugs) and was used for all analytes other than the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs). The analyte coverage included a broad range of commonly prescribed drugs including over the counter medications, commonly misused drugs and metabolites of many of the compounds too. This approach provided a very powerful drug screening tool to investigate drug use/misuse before and whilst in prison. The second methodology (SCRA Screen) was specifically designed for SCRAs and targets only those compounds. This was a very sensitive methodology with a method capability of sub 100pg/ml for over 600 SCRAs and their metabolites. Both methodologies utilised full scan high resolution accurate mass LCMS technologies that allowed a non-targeted approach to data acquisition and the ability to retrospectively review data. The non-targeted approach to data acquisition effectively means that the analyte coverage of the data acquisition was unlimited. The only limiting factors were related to the chemical nature of the analyte being looked for. The analyte must extract in the sample preparation process; it must chromatograph and it must ionise under the conditions used by the mass spectrometer interface. The final limiting factor was presence in the data processing database. The subsequent study of negative MDT samples across the North West and London and the South East used a GCMS methodology for anabolic steroids in addition to the General and SCRA screens. -

Systematic Evaluation of 1-Chlorobutane for Liquid-Liquid Extraction of Drugs U

Systematic evaluation of 1-chlorobutane for liquid-liquid extraction of drugs U. Demme1*, J. Becker2, H. Bussemas3, T. Daldrup4, F. Erdmann5, M. Erkens6, P.X. Iten7, H. Käferstein8, K.J. Lusthof9, H.J. Magerl10, L.v. Meyer11, A. Reiter12, G. Rochholz13, A. Schmoldt14, E. Schneider15, H.W. Schütz13, T. Stimpfl16, F. Tarbah17, J. Teske18, W. Vycudilik16, J.P. Weller18, W. Weinmann19 *On behalf of the “Workgroup Extraction“ of the GTFCh (Society of Toxicological and Forensic Chemistry, Germany) Institutes of Forensic Medicine of 1Jena, 2Mainz, 4Duesseldorf, 5Giessen, 7Zuerich (CH), 8Cologne, 10Wuerzburg, 11Munich, 12Luebeck, 13Kiel, 14Hamburg, 16Vienna (A), 18Hannover, 19Freiburg and 3Praxis Labormedizin Dortmund, 6Clin.-Chem. Central Laboratory, Aachen, 9Nat. For. Inst., Den Haag (NL), 15LKA Baden-Wuerttemberg, Stuttgart 17Dubai Police Dept. Introduction In systematic toxicological analysis (STA), chromatographic Experimental Buffer solutions (pH 9) were obtained by dissolving 10 g methods are widely used for the detection of drugs and other organic toxic substances in Na2HPO4 (VWR) in one liter of distilled water. 1-chlorobutane and methanol (analytical biological materials, such as blood, plasma, urine, hair and tissue samples. In most cases grade) were obtained from VWR International (Darmstadt, Germany). Drugs were the applied analytical methods like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS), purchased as pure compounds or as salts from chemical suppliers (Sigma high performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC/DAD), Deissenhofen/Germany and others) or from the pharmaceutical manufacturers and were HPLC/mass spectrometry (LC/MS), or thin-layer chromatography with remission first dissolved in methanol to achieve a concentration of 1 mg/mL. In some instances the spectroscopy (TLC/UV), require sample preparation by extraction prior to analysis. -

Alltech® Drug Standards for the Forensic, Clinical & Pharmaceutical Industries OH

Alltech® Drug Standards For the Forensic, Clinical & Pharmaceutical Industries OH H3C H H H3C H HO Catalog #505B Our Company Welcome to the Grace's Alltech® Drug Standards Catalog W. R. Grace has manufactured high-quality silica for over 150 years. Grace has been behind the scenes for the past 30 years supplying silica to the chromatography industry. Now we’re in the forefront moving beyond silica, developing and delivering innovative complementary products direct to the customer. Grace Davison Discovery Sciences was founded on Grace’s core strength as a premier manufacturer of differentiated media for SPE, Flash, HPLC, and Process chromatography. This core competency is further enhanced by bringing seven well-known global separations companies together, creating a powerful new single source for all your chromatography needs. A Full Portfolio of Chromatography Products to Support Drug Standards: • HPLC Columns • HPLC Accessories • Flash Products • TLC Products • GC Columns • GC Accessories • SPE and Filtration • Equipment • Syringes • Tubing • Vials For complete details, download the Chromatography Essentials catalog from the Grace web site or contact your customer service representative. Alltech - Part of the Grace Family of Products In 2004, Alltech Associates Inc. was acquired by Grace along with the Alltech® Drug Standards product line. Through investment in research and strategic acquisitions, Grace has expanded our product range and global reach while drawing upon the support of the Grace corporate infrastructure and more than 6000 employees globally to support scientific research and analysis worldwide. With key manufacturing sites in North and South America, Europe, and Asia, plus an extensive international sales and distribution network, separation scientists throughout the world can count on timely delivery and expert local technical service. -

Toxicology Reference Material

toxicology Toxicology covers a wide range of disciplines, including therapeutic drug monitoring, clinical toxicology, forensic toxicology (drug driving, criminal and coroners), drugs in sport and work place drug testing, as well as academia and research. Those working in the field have a professional interest in the detection and measurement of alcohol, drugs, poisons and their breakdown products in biological samples, together with the interpretation of these measurements. Abuse and misuse of drugs is one of the biggest problems facing our society today. Acute poisoning remains one of the commonest medical emergencies, accounting for 10-20% of hospital admissions for general medicine [Dargan & Jones, 2001]. Many offenders charged with violent crimes, or victims of violent crime may have been under the influence of drugs at the time the act was committed. The use of mind-altering drugs in the work place, or whilst in control of a motor vehicle places others in danger [Drummer, 2001]. Performance enhancing drugs in sport make for an uneven playing field and distract from the core ethic of sportsmanship. Patterns of drug abuse around the world are constantly evolving. They vary between geographies; from one country to another and even from region to region or population to population within countries. With a European presence, a wide reaching network of global customers and distributors, and activate participation in relevant professional societies, Chiron is well positioned to develop and deliver relevant, and current standards to meet customer demand in this challenging field. Chiron AS Stiklestadvn. 1 N-7041 Trondheim Norway Phone No.: +47 73 87 44 90 Fax No.: +47 73 87 44 99 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.chiron.no Org. -

Application of Microextraction-Based Techniques for Screening-Controlled Drugs in Forensic Context—A Review

molecules Review Application of Microextraction-Based Techniques for Screening-Controlled Drugs in Forensic Context—A Review Samir M. Ahmad 1,2,3,* , Oriana C. Gonçalves 1, Mariana N. Oliveira 1 , Nuno R. Neng 1,4,* and José M. F. Nogueira 1,4,* 1 Centro de Química Estrutural, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal; [email protected] (O.C.G.); [email protected] (M.N.O.) 2 Molecular Pathology and Forensic Biochemistry Laboratory, CiiEM, Campus Universitário—Quinta da Granja, Monte da Caparica, 2829-511 Caparica, Portugal 3 Forensic and Psychological Sciences Laboratory Egas Moniz, Campus Universitário—Quinta da Granja, Monte da Caparica, 2829-511 Caparica, Portugal 4 Departamento de Química e Bioquímica, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.M.A.); [email protected] (N.R.N.); [email protected] (J.M.F.N.) Abstract: The analysis of controlled drugs in forensic matrices, i.e., urine, blood, plasma, saliva, and hair, is one of the current hot topics in the clinical and toxicological context. The use of microextraction- based approaches has gained considerable notoriety, mainly due to the great simplicity, cost-benefit, and environmental sustainability. For this reason, the application of these innovative techniques has become more relevant than ever in programs for monitoring priority substances such as the Citation: Ahmad, S.M.; Gonçalves, main illicit drugs, e.g., opioids, stimulants, cannabinoids, hallucinogens, dissociative drugs, and O.C.; Oliveira, M.N.; Neng, N.R.; Nogueira, J.M.F. Application of related compounds. The present contribution aims to make a comprehensive review on the state- Microextraction-Based Techniques for of-the art advantages and future trends on the application of microextraction-based techniques for Screening-Controlled Drugs in screening-controlled drugs in the forensic context. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation Exactive Plus High-Resolution, Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA FIGURE 2. Schematic diagram of the Exactive Plus high-resolution accurate FIGURE 5. ExactFinder processing method and database. FIGURE 7. LODs for around 490 compounds For targeted screening, ExactFinder uses parameters set in processing method to Overview mass benchtop mass spectrometer. identify and confirm the presence of compound based on database values. Figure 8 Purpose: Evaluate Thermo Scientific Exactive Plus high performance bench-top mass Compound LOD Compound LOD Compound LOD Compound LOD shows data review results for one donor sample. In this method, compounds were 1‐(3‐Chlorophenyl)piperazine 5 Deacetyl Diltiazem 5 Lormetazepam 5 Perimetazine 5 identified by accurate mass within 5 ppm and retention time. Identity was further spectrometer for drug screening of whole blood for forensic toxicology purposes. 10‐hydroxycarbazepine 5 Demexiptiline 5 Loxapine 5 Phenacetin 5 5‐(p‐Methylphenyl)‐5‐phenylhydantoin 10 Des(2‐hydroxyethyl)opipramol 5 LSD 5 Phenazone 5 confirmed by isotopic pattern and presence of known fragments. Methods: Whole blood samples were processed by precipitation with ZnSO / 6‐Acetylcodeine 100 Desalkylflurazepam 5 Maprotiline 5 Pheniramine 5 4 6‐Methylthiopurine 5 Desipramine 5 Maraviroc 5 Phenobarbital 5 Matrix effects were observed to be compound dependent and were generally within methanol. Samples were injected onto an HPLC under gradient conditions and 6‐Monoacetylmorphine 5 Desmethylcitalopram 5 MBDB 5 Phenylbutazone 5 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline 5 Desmethylclozapine 50 MDEA 5 Phenytoin 10 ±50%. -

Moore Hair Analysis for Drugs: Cutoffs, Analytes, Stability. DTAB July 2013

Hair Analysis for Drugs: Cut-off Concentrations Analytes Stability Christine Moore PhD, DSc Immunalysis Corporation Drug Testing Advisory Board July 15th 2013 Overview • Proposed Guidelines • Cut-off concentrations • Analytes • Drug stability • Further considerations for program Rates of ED visits per 100,000 population involving illicit drugs, 2011 Drug Rate of ED visits per 100,000 population Cocaine 162 Marijuana 146 Heroin 83 Amphetamines/methamphetamines 51 PCP 24 Proposed Guidelines: Immunoassay / Screening • Recommended cut-off (pg/mg) Drug DTAB 2004 EWDTS 2010 SOHT 2012 Phencyclidine 300 -- -- Opiates 200 200 200 Cocaine 500 500 500 Amphetamines 500 200 200 Cannabinoids 1 50 50 Methadone -- -- 200 Buprenorphine -- -- 10 Benzodiazepines -- 50 -- Proposed screening cut-off concentrations DTAB 2004, EWDTS 2010, SOHT 2012, Drug pg/mg pg/mg pg/mg Opiates 200 200 200 Cocaine 500 500 500 Amphetamines 500 200 200 Cannabinoids 1 50 50 Considerations for immunoassay: Cocaine Drug Urine, % Hair,% Cocaine 5 60 BZE 90 25 CE 0 10 Norcocaine 0 5 Considerations for immunoassay: Heroin Drug Urine, % Hair, % Heroin 0 10 6-AM 5 50 Morphine 10 35 M-3-g, M-6-g 85 2 Targeted immunoassay screens • Basic drugs: • Incorporate well into hair • Parent compound (e.g. cocaine) incorporated to greater extent than metabolites (e.g. BZE) • So immunoassay must target cocaine, OR, if urine immunoassay used, degree of conversion of cocaine to BZE in method must be measured • 6-AM in higher concentration than morphine • Immunoassay should target 6-AM, OR, degree -

2021 Equine Prohibited Substances List

2021 Equine Prohibited Substances List . Prohibited Substances include any other substance with a similar chemical structure or similar biological effect(s). Prohibited Substances that are identified as Specified Substances in the List below should not in any way be considered less important or less dangerous than other Prohibited Substances. Rather, they are simply substances which are more likely to have been ingested by Horses for a purpose other than the enhancement of sport performance, for example, through a contaminated food substance. LISTED AS SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY BANNED 1-androsterone Anabolic BANNED 3β-Hydroxy-5α-androstan-17-one Anabolic BANNED 4-chlorometatandienone Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androst-2-ene-17one Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3α, 17α-diol Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3α, 17β-diol Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3β, 17α-diol Anabolic BANNED 5α-Androstane-3β, 17β-diol Anabolic BANNED 5β-Androstane-3α, 17β-diol Anabolic BANNED 7α-Hydroxy-DHEA Anabolic BANNED 7β-Hydroxy-DHEA Anabolic BANNED 7-Keto-DHEA Anabolic CONTROLLED 17-Alpha-Hydroxy Progesterone Hormone FEMALES BANNED 17-Alpha-Hydroxy Progesterone Anabolic MALES BANNED 19-Norandrosterone Anabolic BANNED 19-Noretiocholanolone Anabolic BANNED 20-Hydroxyecdysone Anabolic BANNED Δ1-Testosterone Anabolic BANNED Acebutolol Beta blocker BANNED Acefylline Bronchodilator BANNED Acemetacin Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug BANNED Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant CONTROLLED Acepromazine Sedative BANNED Acetanilid Analgesic/antipyretic CONTROLLED Acetazolamide Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor BANNED Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant CONTROLLED Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic BANNED Acetophenazine Antipsychotic BANNED Acetophenetidin (Phenacetin) Analgesic BANNED Acetylmorphine Narcotic BANNED Adinazolam Anxiolytic BANNED Adiphenine Antispasmodic BANNED Adrafinil Stimulant 1 December 2020, Lausanne, Switzerland 2021 Equine Prohibited Substances List . Prohibited Substances include any other substance with a similar chemical structure or similar biological effect(s). -

Indications for Use Form

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue Document Control Center – WO66-G609 Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002 June 27, 2016 GUANGZHOU WONDFO BIOTECH CO., LTD. C/O JOE SHIA 504 E DIAMOND AVE., SUITE I GAITHERSBURG MD 20877 Re: k161214 Trade/Device Name: Wondfo Amphetamine Urine Test AMP 500 (Cup, Dipcard), Wondfo Cocaine Urine Test COC 150(Cup, Dipcard), Wondfo Methamphetamine Urine Test MET 500 (Cup, Dipcard) Regulation Number: 21 CFR 862.3250 Regulation Name: Cocaine and cocaine metabolite test system Regulatory Class: II Product Code: DIO, DKZ, DJC Dated: April 21, 2016 Received: April 29, 2016 Dear Mr. Shia: We have reviewed your Section 510(k) premarket notification of intent to market the device referenced above and have determined the device is substantially equivalent (for the indications for use stated in the enclosure) to legally marketed predicate devices marketed in interstate commerce prior to May 28, 1976, the enactment date of the Medical Device Amendments, or to devices that have been reclassified in accordance with the provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Act) that do not require approval of a premarket approval application (PMA). You may, therefore, market the device, subject to the general controls provisions of the Act. The general controls provisions of the Act include requirements for annual registration, listing of devices, good manufacturing practice, labeling, and prohibitions against misbranding and adulteration. Please note: CDRH does not evaluate information related to contract liability warranties. We remind you, however, that device labeling must be truthful and not misleading.