My Last Duchess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God Is the Perfect Poet

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God is the perfect poet. – Paracelsus by Robert Browning NUMBER 51 SPRING/SUMMER 2007 WACO, TEXAS Ann Miller to be Honored at ABL For more than half a century, the find inspiration. She wrote to her sister late Professor Ann Vardaman Miller of spending most of the summer there was connected to Baylor’s English in the “monastery like an eagle’s nest Department—first as a student (she . in the midst of mountains, rocks, earned a B.A. in 1949, serving as an precipices, waterfalls, drifts of snow, assistant to Dr. A. J. Armstrong, and a and magnificent chestnut forests.” master’s in 1951) and eventually as a Master Teacher of English herself. So Getting to Vallombrosa was not it is fitting that a former student has easy. First, the Brownings had to stepped forward to provide a tribute obtain permission for the visit from to the legendary Miller in Armstrong the Archbishop of Florence and the Browning Library, the location of her Abbot-General. Then, the trip itself first campus office. was arduous—it involved sitting in a wine basket while being dragged up the An anonymous donor has begun the cliffs by oxen. At the top, the scenery process of dedicating a stained glass was all the Brownings had dreamed window in the Cox Reception Hall, on of, but disappointment awaited Barrett the ground floor of the library, to Miller. Browning. The monks of the monastery The Vallombrosa Window in ABL’s Cox Reception The hall is already home to five windows, could not be persuaded to allow a woman Hall will be dedicated to the late Ann Miller, a Baylor professor and former student of Dr. -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Women and Nationalistic Politics in Robert Browning’S Poetry: a Feminist Reading of ‘’Balaustion’S Adventure and ‘’Aristophanes Apology

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN (P): 2249-6912; ISSN (E): 2249-8028 Vol. 7, Issue 4, Aug 2017, 43-64 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd WOMEN AND NATIONALISTIC POLITICS IN ROBERT BROWNING’S POETRY: A FEMINIST READING OF ‘’BALAUSTION’S ADVENTURE AND ‘’ARISTOPHANES APOLOGY IGNATIUS NSAIDZEDZE Department of English, Faculty of Arts the University of Buea, South West Region, America ABSTRACT Using the feminist critical theory, this paper analyses two epic poems by Robert Browning telling the story of a 14 year old girl from Rhodes, an ally of Athens who was using Euripides as her idol and his tragedy as her weapon liberates Athens from Spartan occupation with its foreign comedy of Aristophanes.Balaustion here is similar to Saint Joan in George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan who liberates the French nation from the English occupation.The paper argues that Balaustion portrays herself as a ‘’New-Woman’’ when she exhibits masculine attributes like Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, her patriotism/nationalism and her quest for her people’s freedom when she liberates Athens from Spartan occupation.This paper reveals that by portraying such an active, nationalistic, man-like woman, Browning simply was paying tribute to his dead wife Elizabeth Barrett Browning who had died earlier.The story of King Admetos and his wife Alcestis paralleled that of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Browning and his wife were fervent admirers of the youngest of the three Greek tragedians Euripides and these two epics equally show Euripides’ importance as a nationalist tragedian in the ancient Greek world coming after Aeschylus and Sophocles. -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Poems Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ROBERT AND ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING POEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Browning,Elizabeth Barrett Browning,Peter Washington | 256 pages | 28 Feb 2003 | Everyman | 9781841597522 | English | London, United Kingdom Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Poems PDF Book Alexander Neubauer. A blue plaque at the entrance to the site attests to this. Retrieved 23 October Virginia Woolf called it "a masterpiece in embryo". Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in Florence on June 29, Her mother's collection of her poems forms one of the largest extant collections of juvenilia by any English writer. Retrieved 22 September Here's another love poem from the Portuguese cycle , too, Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. Olena Kalytiak Davis Fredeman and Ira Bruce Nadel. Carl Sandburg Here's a very brief primer on a bold and brilliant talent. In the newly elected Pope Pius IX had granted amnesty to prisoners who had fought for Italian liberty, initiated a program looking forward to a more democratic form of government for the Papal State, and carried out a number of other reforms so that it looked as though he were heading toward the leadership of a league for a free Italy. During this period she read an astonishing amount of classical Greek literature—Homer, Pindar, the tragedians, Aristophanes, and passages from Plato, Aristotle, Isocrates, and Xenophon—as well as the Greek Christian Fathers Boyd had translated. Her prolific output made her a rival to Tennyson as a candidate for poet laureate on the death of Wordsworth. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Vice-Presidents: Robert Browning Esq. Burton Raffel. Sandra Donaldson et al. -

My Last Duchess Porphyria's Lover Robert Browning 1812–1889

The Influence of Romanticism My Last Duchess RL 1 Cite strong and thorough Porphyria’s Lover textual evidence to support inferences drawn from the Poetry by Robert Browning text. RL 5 Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts KEYWORD: HML12-944A of a text contribute to its overall VIDEO TRAILER structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact. RL 10 Read and comprehend literature, Meet the Author including poems. SL 1 Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions. Robert Browning 1812–1889 “A minute’s success,” remarked the poet character in an emotionally charged situation. Robert Browning, “pays for the failure of While critics attacked his early dramatic years.” Browning spoke from experience: poems, finding them difficult to understand, did you know? for years, critics either ignored or belittled Browning did not allow the reviews to keep his poetry. Then, when he was nearly 60, him from continuing to develop this form. Robert Browning . he became an object of near-worship. • became an ardent Secret Love In 1845, Browning met the admirer of Percy Bysshe Precocious Child An exceptionally bright poet Elizabeth Barrett and began a famous Shelley at age 12. child, Browning learned to read and write romance that has been memorialized in both • achieved fluency in by the time he was 5 and composed his film and literature. Against the wishes of Latin, Greek, Italian, and first, unpublished volume of poetry at Barrett’s overbearing father, the two poets French by age 14. 12. At the age of 21 he published his first married in secret in 1846 and eloped to • wrote the children’s book, Pauline (1833), to negative reviews. -

Fabienne Moine Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Italian Poetry

Fabienne Moine Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Italian Poetry: Constructing National Identity and Shaping the Poetic Self After Elizabeth Barrett married the poet Robert Browning in 1846, the newly-wed couple settled in Italy, a soothing place for Elizabeth’s poor health and a land of psychological independence, very unlike the prison-like house of Wimpole Street where her father had kept her away from any suitor. From her Florentine windows in Casa Guidi, the famous poet contemplated Italian history in the making during the Risorgimento. There she wrote one of her best poems, Aurora Leigh (1856), an aesthetic autobiography in verse. This epic poem would hardly have been so successful had she not previously writ- ten her political verse Casa Guidi Windows. In the two parts of this poem committed to the birth of the new nation, Barrett Browning reveals how deeply engaged she is in the Italian cause. Indeed, the last fifteen years of her artistic life were dedicated to the country which welcomed the poet and opened new perspectives in terms of poetical writing. From 1846 onwards, Barrett Browning unceasingly appealed to and supported the Italian people and openheartedly fought for the freedom of the country in her poems: Casa Guidi Windows, Poems Before Congress, and Last Poems published post- humously and after she had been buried in the English cemetery in Florence. Barrett Browning had a personal approach to Italy entirely different from her husband’s who could stroll about Florentine streets. She would stay behind her windows, as the title -

The Portal Wide...” News from the Armstrong Browning Library

“A wondrous portal opened The Portal wide...” News from the Armstrong Browning Library Number 53 • Spring 2009 Browning Day to be Held May 7, 2009 Browning Day! The very sound of it implies poetry Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s family papers. As a and music. This annual celebration of the collective collector, mainly of Robert Browning and his friends, ABL STAFF birthdays of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Meredith is a member of the Roxburghe Club and the and the Armstrong Browning Library’s founder, Dr. Grolier Club of New York. He is the general editor Rita S. Patteson A. J. Armstrong, provides a venue for patrons to of The Poetical Works of Robert Browning, published by Interim Director & catch up on what has been happening at the Library Oxford University Press, and is co-editor of volume Associate Professor/Curator and to reconnect with each other. 15, Parleyings and Asolando, which is to be released this of Manuscripts year. He has written extensively on the Brownings, and Thursday, May 7, at 2:30 pm, Michael Meredith, he is about to complete his third term as president of Dr. Avery T. Sharp Curator of the Modern Collections at Eton the Browning Society of London. Professor/Museum College, will speak on the topic “Robert Browning Coordinator and the Actors.” Meredith is currently sketching The ABL has enjoyed a long friendship with Eton and Research Librarian out ideas for a new book, provisionally called The College. In 1983, at the suggestion of Meredith, Hidden Browning, which will include a chapter on Eton’s Provost and Fellows donated to ABL a plaster Cynthia A. -

Overseas 2011

overSEAS 2011 This thesis was submitted by its author to the School of Eng- lish and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. It was found to be among the best theses submitted in 2011, therefore it was decorated with the School’s Outstanding Thesis Award. As such it is published in the form it was submitted in overSEAS 2011 (http://seas3.elte.hu/overseas/2011.html) C ERTIFICATE OF R ESEARCH By my signature below, I certify that my ELTE MA thesis, entitled “And I Choose Never to Stoop”: Focalisation and Diegesis in Robert Browning’s Complementary Dramatic Monologues is entirely the result of my own work, and that no degree has previously been conferred upon me for this work. In my thesis I have cited all the sources (printed, electronic or oral) I have used faithfully and have always indicated their origin. The electronic version of my thesis (in PDF format) is a true representation (identical copy) of this printed version. If this pledge is found to be false, I realize that I will be subject to penalties up to and including the forfeiture of the degree earned by my thesis. Date: 2nd May 2011. Signed: ....................................................... “And I Choose Never to Stoop”: Focalisation and Diegesis in Robert Browning’s Complementary Dramatic Monologues „Márpedig sértést nem tűrök”: Fokalizáció és diegézis Robert Browning párverseiben SZAKDOLGOZAT Vesztergom Janina Témavezető: Dr. Csikós Dóra egyetemi adjunktus MA in English Anglisztika MA Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem 2011 Abstract The first and foremost aim of my thesis is to demonstrate that a comparative analysis of Robert Browning‟s complementary dramatic monologues, “My Last Duchess – Ferrara” and “Count Gismond – Aix en Provence”, does not only lead to a better understanding of the individual poems, but also draws the readers‟ attention to significant aspects of interpretation which otherwise would remain unnoticed. -

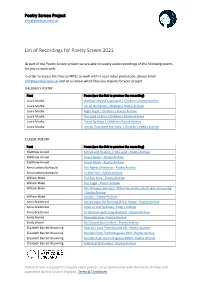

List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021

Poetry Screen Project [email protected] List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021 As part of the Poetry Screen project we are able to supply audio recordings of the following poems for you to work with. In order to access this files as MP3s to work with in your video production, please email [email protected] and let us know which files you require for your project. CHILDREN’S POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Laura Mucha Wanted: Wizard's Assistant | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha I'm an Orchestra | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Night Flight | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha The Land of Blue | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Travel By Book | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Words That Make Me Smile | Children's Poetry Archive CLASSIC POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Matthew Arnold Sohrab and Rustum, ll. 857–end - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld The Rights of Woman - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld To the Poor - Poetry Archive William Blake The Sick Rose - Poetry Archive William Blake The Tyger - Poetry Archive William Blake The Chimney Sweeper: 'When my mother died I was very young' - Poetry Archive William Blake London - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Verses Upon the Burning of Our House - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Upon a Fit of Sickness - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet To My Dear and Living Husband - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté Remembrance - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté No Coward Soul Is Mine - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning How do I Love Thee (Sonnet 43) - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets From The Portuguese XXIV - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets from the Portuguese XXXVI - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning A Musical Instrument - Poetry Archive Poetry Screen is a project to inspire video poetry, run in partnership with the Poetry Archive and supported by Arts Council England.