Screening for Colorectal Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

MEDICAL POLICY – 2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome BCBSA Ref. Policy: 2.04.26 Effective Date: July 1, 2021 RELATED MEDICAL POLICIES: Last Revised: June 8, 2021 None Replaces: N/A Select a hyperlink below to be directed to that section. POLICY CRITERIA | DOCUMENTATION REQUIREMENTS | CODING RELATED INFORMATION | EVIDENCE REVIEW | REFERENCES | HISTORY ∞ Clicking this icon returns you to the hyperlinks menu above. Introduction Intestinal dysbiosis is a condition that occurs when the microorganisms in the digestive tract are out of balance. This condition is believed to cause diseases of the digestive tract, including poor nutrient absorption, overgrowth of certain bacteria, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Symptoms of these digestive problems are similar and may include: abdominal pain, excess gas, bloating, and changes in bowel movements (constipation or diarrhea, or both). One method of diagnosing digestive disorders is by testing a fecal sample. Using fecal analysis to diagnose intestinal dysbiosis, IBS, malabsorption, or small intestinal overgrowth of bacteria is unproven (investigational). More studies are needed to see if this testing improves health outcomes. Note: The Introduction section is for your general knowledge and is not to be taken as policy coverage criteria. The rest of the policy uses specific words and concepts familiar to medical professionals. It is intended for providers. A provider can be a person, such as a doctor, nurse, psychologist, or dentist. A provider also can be a place where medical care is given, like a hospital, clinic, or lab. This policy informs them about when a service may be covered. -

An Osteopathic Approach to Reduction of Readmissions for Neonatal Jaundice

Osteopathic Family Physician (2013) 5, 17–23 REVIEW ARTICLE An osteopathic approach to reduction of readmissions for neonatal jaundice Rachel Click, DO,a Julie Dahl-Smith, DO,a Lindsay Fowler, DO,a Jacqueline DuBose, MD,a Margi Deneau-Saxton, RN, CCCE, CIMI, CLC, CPD,b Jennifer Herbert, MDc From aGeorgia Health Sciences University, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Family Medicine, GA; bGeorgia Health System, OB Labor and Delivery, GA; and cUniversity Primary Care, Evans, GA. KEYWORDS: Jaundice is a potentially life-threatening condition that continues to affect at-risk newborns, accounting Breastfeeding; for continued hospital readmissions. As family physicians, we should be cognizant of neonates who may Jaundice; be at risk for jaundice, including those with pathologic jaundice as well as newborns of breastfeeding Prevention; mothers, and ensure sufficient intervention is taken to help prevent further elevations in bilirubin levels. Hyperbilirubinemia; Interventions are likely to include evaluation for sepsis, education regarding feeding frequencies for both Neonatal massage breast- and bottle-fed neonates, reviewing maternal and hematologic risk factors for neonatal jaundice, and considering inborn errors of metabolism. An additional measure family physicians may consider is that of neonatal massage for those with elevated bilirubin levels. Neonatal massage, though not widely used, has been proven to promote excess bilirubin excretion, thus decreasing length of hospital stay; all the while, providing an intervention that allows parents to take an active role. r 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction morbidity rate with bilirubin 4 20 mg/dL. “It has been estimated that the risk of kernicterus in infants with total Jaundice is a product of excess bilirubin (a product of serum bilirubin (TSB) greater than 30 mg/dL is about 1 in broken down red blood cells), which manifests as a 7 infants”.1 Less serious complications of hyperbilirubine- yellowing of the skin and eyes. -

INFORMED CARING JAUNDICE Neonatal Jaundice BILIARY

1 INFORMED CARING Situations with Adults and Children with Gallbladder, Liver and Pancreatic Disorders 2 JAUNDICE ä Does NOT mean hepatitis ä Increased breakdown of RBCs ä Altered bilirubin breakdown ä Impeded flow through liver or bile duct ä First seen in sclera, then skin 3 Neonatal Jaundice ä Not liver failure ä RBC breakdown ä Phototherapy 4 BILIARY ATRESIA ä Jaundice 2-3 weeks after birth ä Easy bruising ä Stools putty like ä Tea colored urine ä Abdominal/organ distension 5 4 F’s of Gallbladder ä Fair ä Fat X size of person X amount in diet ä Fertile X BCP X Multiparity ä Forty 6 Cholelithiasis ä Calculi within the duct or gallbladder ä Severe colicky, cramp-like pain X radiates to shoulder blade X Murphy's sign ä Cholecystitis: inflammation X Can be caused by trauma, fasting, TPN or abdominal surgery 7 Diagnostic Studies ä Ultrasound of abdomen 1 X not for the obese ä HIDA scan X nuclear medicine ä Cholangiograms X endoscopic X transvenous X intraoperative 8 Post-op Care ä High abdominal incision X respiratory compromise ä T-tube X patients need to know how to empty it X may clamp it prior to removal X caution not dislodged with movements ä NO Morphine X spasms of sphincter of Oddi 9 Post-op Nutrition ä Limited fat in diet X can have rapid transit times ä Potential fat soluble vitamin deficit X A, D, E and K ä Weight loss diet 10 LIVER FAILURE ä Cirrhosis ä Drug toxicity X acetaminophen, anesthetics, HCTZ, chemotherapy ä Infection ä Cancer ä ETOH is single most linked cause 11 LIVER FAILURE S/S ä Don’t show up until 80-90% failed -

Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21

20 Osteopathic Family Physician (2019) 20 - 25 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 11, No. 2 | March/April, 2019 Gennaro, Larsen Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21 Review ARTICLE to escape. This mechanism prevents the stomach from becoming IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS) Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating damaged by excessive dilation.2 IBS is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered with OMT Treatment Options Many patients with GERD report increased belching. Transient bowel habits. It is the most commonly diagnosed GI disorder lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation is the major and accounts for about 30% of all GI referrals.7 Criteria for IBS is recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the Carly Gennaro, DO1; Helaine Larsen, DO1 mechanism for both belching and GERD. Recent studies have shown that the number of belches is related to the number of last three months associated with at least two of the following: times someone swallows air. These studies have concluded that 1) association with defecation, 2) change in stool frequency, 1 Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, West Islip, NY patients with GERD swallow more air in response to heartburn and 3) change in stool form. Diagnosis should be made using these therefore belch more frequently.3 There is no specific treatment clinical criteria and limited testing. Common symptoms are for belching in GERD patients, so for now, physicians continue to abdominal pain, bloating, alternating diarrhea and constipation, treat GERD with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2 and pain relief after defecation. Pain can be present anywhere receptor antagonists with the goal of suppressing heartburn and in the abdomen, but the lower abdomen is the most common KEYWORDS: ABSTRACT: Intestinal gas production is a normal physiologic progress. -

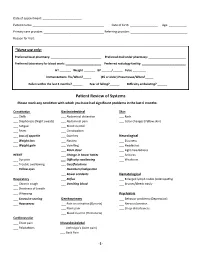

Patient Review of Systems Please Mark Any Condition with Which You Have Had Significant Problems in the Last 6 Months

Date of appointment: ________________________ Patient name: ____________________________________________ Date of birth: _________________ Age: ___________ Primary care provider: _____________________________________ Referring provider: ___________________________________ Reason for Visit: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ *Nurse use only: Preferred local pharmacy: _______________________________ Preferred mail order pharmacy: _______________________ Preferred laboratory for blood work: ______________________ Preferred radiology facility: ___________________________ HT _______ Weight _______ BP ______/______ Pulse ________ Immunizations: Flu/When?_____ (65 or older) Pneumovax/When?_____ Fallen within the last 3 months? ______ Fear of falling?______ Difficulty ambulating? ______ Patient Review of Systems Please mark any condition with which you have had significant problems in the last 6 months: Constitution Gastrointestinal Skin ___ Chills ___ Abdominal distention ___ Rash ___ Diaphoresis (Night sweats) ___ Abdominal pain ___ Color changes (Yellow skin) ___ Fatigue ___ Blood in stool ___ Fever ___ Constipation ___ Loss of appetite ___ Diarrhea Neurological ___ Weight loss ___ Nausea ___ Dizziness ___ Weight gain ___ Vomiting ___ Headaches ___ Black stool ___ Light-headedness HEENT ___ Change in bowel habits ___ Seizures ___ Eye pain ___ Difficulty swallowing ___ Weakness ___ Trouble swallowing ___ Gas/flatulence ___ Yellow eyes ___ Heartburn/indigestion ___ Bowel accidents Hematological -

Traveller's Diarrhoea (TD) Is the Commonest Health

Diarrhoea • THEME Traveller's diarrhoea BACKGROUND There has been little if any Traveller's diarrhoea (TD) is the commonest health change in the incidence of traveller's diarrhoea problem facing travellers to less developed countries over the past 20 years. of the world. It is costly to both the traveller (time lost) and the host country (eg. cancelled activities). OBJECTIVE This article aims to provide a basic understanding on why travellers are more likely to Definition experience diarrhoea during travel. Classic TD is described as three or more loose bowel DISCUSSION In a 20 minute pretravel actions with at least one of the following accompanying consultation time is precious, and providing symptoms: nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps or information on traveller's diarrhoea often has pain, fever or blood in the stools. Lesser degrees a low priority over prescribing the necessary vaccinations and discussing antimalarials. (moderate or mild) of TD are also described. Severity is Bob Kass, Travellers do not follow the rules of eating and usually defined by the number of bowel actions per 24 drinking safely, and diarrhoea is common. 'What hour period (severe >6). According to the World Health MBBS, MRCP (UK), MScMCH, Organisation, symptoms lasting less than 14 days may to do in the event of illness' is an important DCH, FAFPHM, consideration. Presumptive treatment should be defined as 'acute diarrhoea', and those lasting more is a consultant, be offered to all travellers whose itinerary and than 14 days 'persistent diarrhoea'.1 International Public activities put them at risk. Between 30 and 50% of travellers will be affected Health Medicine, Rede-Health in a 2 week overseas stay, with approximately 12% International. -

Type 2 Diabetes SCAN Formulary Drugs

Pharmacologic Agents for Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes SCAN Formulary Drugs 2020 2021 Risk for Dosing & Drug- Drug Medication Formulary Formulary Adverse Drug Reactions Administration Interactions Tier UM Tier UM * Biguanides 500 – 850 mg Nausea/ vomiting, GI upset, metallic taste, metformin tabs 1 1 QD - TID diarrhea, flatulence, lactic acidosis (rare) metformin er Neutral 500 – 2000 mg Nausea/ vomiting, GI upset, diarrhea, flatulence, uncoated tabs 1 1 daily lactic acidosis 500 mg & 750 mg Sulfonylureas Dizziness, headache, hypoglycemia, nausea, glimepiride 1 1 1 – 8 mg daily weight gain 2.5 – 20 mg Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, diarrhea, glipizide 1 1 daily Moderate hypoglycemia, nausea, weight gain Asthenia, headache, dizziness, rash, nausea, glipizide er 1 1 5 – 20 mg daily hypoglycemia, weight gain glipizide / 2.5 / 500 mg Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, nausea, 1 1 Moderate metformin tabs BID flatulence, hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis Thiazolidinediones & Thiazolidinedione Combination Agents 15 – 45 mg Anemia, edema, weight gain, headache, myalgia, pioglitazone 1 1 daily bone fracture, heart failure 15 / 500 mg – pioglitazone / Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, nausea, 2 2 45 / 1500mg metformin Neutral flatulence, hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis daily 15 / 500 mg – pioglitazone / Anemia, edema, weight gain, headache, myalgia, 2 [QL] 2 [QL] 45 / 2550 mg glimepiride dizziness, hypoglycemia, nausea daily R. Brower and N. Nguyen rev. 11/2012; R. Brower rev. 11/2013, 9/2014, 11/2015; D. Yoon rev 8/2016, 11/2016, 8/2017; K. -

Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Diet

Irritable bowel syndrome and diet What is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)? IBS is a very common condition. It describes a wide range of symptoms that vary from one person to another and can be worse for some people than others. The most common symptoms are: • wind and/or bloating • feeling the need to open the bowels even after • diarrhoea or constipation, or both having just been to the toilet • low abdominal pain, which may ease after opening the • a feeling of urgency bowels or be accompanied by a change in bowel habit • feeling that your symptoms are worse after or stool appearance eating. • passing mucus If you have any of the following symptoms consult your doctor immediately: unintentional and unexplained weight loss; rectal bleeding; a family history of bowel or ovarian cancer; if you are over 60 years old, a change in bowel habit to looser and/or more frequent stools for more than 6 weeks. Before attempting to manage symptoms via your diet, it is important to rule our other medical conditions, and to have a diagnosis established by your doctor or healthcare professional. Ensure that you: Helpful hints: • eat regular meals • keep a food and symptom diary to see if • do not skip meals or eat late at night diet affects your symptoms. Remember • take your time when eating meals symptoms may not be caused by the food • sit down to eat and chew your food well you have just eaten, but what you ate • take regular exercise – for example, earlier that day or the day before. walking, cycling or swimming • give your bowels time to adjust to any • make time to relax. -

Standard of Care: Anorectal Disorders ICD 10 Codes

Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Anorectal Disorders ICD 10 Codes: Constipation (outlet dysfunction): K5902 Anal Spasm: K594 Constipation (NEC): K5900 Other Specified Diseases of Anus or Rectum: K6289 Fecal Incontinence (full): R159 Fecal Incontinence (incomplete emptying): R150 Fecal Incontinence (smearing): R151 Fecal Incontinence (fecal urgency): R152 Additional ICD-10 codes that may be used to address common coexisting impairments: Pelvic muscle wasting: N8184 Rectocele: N816 Muscle spasm: M62838 Case Type / Diagnosis: dyssynergic defecation (outlet dysfunction); slow transit constipation, fecal incontinence, anorectal pain/Levator Ani Syndrome, proctalgia fugax Anorectal disorders encompass multiple diagnoses including: dyssynergic defecation, fecal incontinence and levator ani syndrome, all of which are evaluated and treated in pelvic health physical therapy. The current Rome IV diagnostic criterion (released in May 2016), which is the standard for clinical practice and research for functional gastrointestinal disorders, recognizes several anorectal disorders, including: fecal incontinence, functional anorectal pain, and functional defecation disorders and functional constipation.1 Please refer to the tables below for complete review of the Rome IV diagnostic criteria for each condition. 1,2 . Anorectal disorders are common and affect up to 25% of the adult and pediatric population, causing a significant negative impact on quality of life and a burden to health care. 3 The exact definition of fecal incontinence and anal incontinence is important in differential diagnosis for the pelvic floor physical therapist. Fecal incontinence, (FI) as defined by Bharucha, is uncontrolled passage of fecal material recurring for less than or equal to 3 months and is not considered a medical problem before age four. -

Review of Systems

Review of Systems Name:_____________________________________ DOB:_________________ Date:___________________ Sex:___________ Age:_________________ General None Yes No Lymph_ None Yes No Pain ▢ ▢ Yes No Fever ▢ ▢ Discharge ▢ ▢ Tender nodes ▢ ▢ Chills ▢ ▢ Other:________________________ Enlargement ▢ ▢ Malaise ▢ ▢ Other:________________________ Fatigue ▢ ▢ Ears None Night sweats ▢ ▢ Yes No Endocrine None Weight changes ▢ ▢ Hearing loss ▢ ▢ Yes No Other:________________________ Pain ▢ ▢ Heat/cold intolerance ▢ ▢ Discharge ▢ ▢ Weight change ▢ ▢ Diet None Vertigo ▢ ▢ Increased thirst ▢ ▢ Yes No Ringing in the ears ▢ ▢ Increased urination ▢ ▢ Appetite ▢ ▢ Other:________________________ Hair changes ▢ ▢ Restrictions ▢ ▢ Other:________________________ Vitamins ▢ ▢ Nose None Supplements ▢ ▢ Yes No Female None Other:________________________ Congestion ▢ ▢ Yes No Nose bleeds ▢ ▢ Changes in menses ▢ ▢ Skin, Hair & Nails None Postnasal drip ▢ ▢ Pain with intercourse ▢ ▢ Yes No Changes in smell ▢ ▢ New partners ▢ ▢ Rash ▢ ▢ Other:________________________ Changes in contraception ▢ ▢ Eruptions ▢ ▢ Menopausal symptoms ▢ ▢ Itching ▢ ▢ Throat & Mouth None LMP________________________ Pigment changes ▢ ▢ Yes No Other:________________________ Hair loss/changes ▢ ▢ Hoarseness ▢ ▢ New moles ▢ ▢ Sore throat ▢ ▢ Male None Lesions /sores ▢ ▢ Bleeding gums ▢ ▢ Yes No Other:________________________ Ulcers ▢ ▢ Puberty onset ▢ ▢ Tooth problems ▢ ▢ Erections ▢ ▢ Head & Neck None Difficulty swallowing ▢ ▢ Testicular pain ▢ ▢ Yes No Changes in voice ▢ ▢ Libido ▢ ▢ Headaches -

What Your Farts Are Telling You About Your Health

WHAT YOUR FARTS ARE TELLING YOU ABOUT YOUR HEALTH ALEXA ERICKSONDECEMBER 6, 2016 Bodily functions can be less than appealing most of the time, causing the discussion of them to be taboo, or at least embarrassing for many. But discussing them can lead to a lot of deeper knowledge about your own body, so that you can better understand your health, which is something that’s most certainly not a taboo subject. Though flatulence is often left for comedy, and considered impolite, gross and unsexy to say the least, it happens. And it happens for a reason. In fact, farts can say so much about your health and wellness, almost making it pertinent that we pick through the topic much more openly than we currently do. What Exactly Are Farts? Besides funny, smelly, sometimes loud occurrences, they’re also a mix of swallowed air that enters the digestive system by accident while breathing, causing gas to be produced by the bacteria in your lower intestine. The gas is created via the breakdown of sugars and starches that your body has trouble digesting. This breakdown generates about 2 and 6 cups of gas every day. Once it builds up, however, it must be emptied. And that’s when farting happens. So is it good? Yes! If you’re farting regularly, it means you’re eating plenty of fiber, and have a good amount of bacteria in your intestines. What The Type of Fart Reveals About Your Health There are many types of farts. Loud, silent, smelly. But what do they all mean? As for stinky farts, this scent is the result of hydrogen sulfide, which is the gas created when your body breaks down foods with sulfur in them. -

In the Clinic

in the clinic Irritable Bowel Syndrome Diagnosis page ITC7-2 Treatment page ITC7-8 Practice Improvement page ITC7-14 Patient Information Page page ITC7-15 CME Questions page ITC7-16 Section Editors The content of In the Clinic is drawn from the clinical information and Christine Laine, MD, MPH education resources of the American College of Physicians (ACP), including David Goldmann, MD PIER (Physicians’ Information and Education Resource) and MKSAP (Medical Knowledge and Self-Assessment Program). Annals of Internal Medicine Science Writer editors develop In the Clinic from these primary sources in collaboration with Jennifer F. Wilson the ACP’s Medical Education and Publishing Division and with the assistance of science writers and physician writers. Editorial consultants from PIER and MKSAP provide expert review of the content. Readers who are interested in these primary resources for more detail can consult http://pier.acponline.org and other resources referenced in each issue of In the Clinic. The information contained herein should never be used as a substitute for clinical judgment. © 2007 American College of Physicians Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by McGill University, Teresa Rudkin on 04/08/2016 in the clinic rritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common but poorly understood dis- order that interferes with normal colon function, resulting in abdominal I pain, bloating, constipation, and diarrhea. No specific biological bio- marker, physiologic abnormality, or anatomical defect has been discovered. Psychosocial stress may exacerbate symptoms. IBS is 1 of 28 adult and 17 pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. These disorders are symptom-based and not explained by other pathologically defined diseases.