Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters Enabling Actions Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquamarine Power – Oyster* Biopower Systems – Biowave

Wave Energy Converters (WECs) Aquamarine Power – Oyster* The Oyster is uniquely designed to harness wave energy in a near-shore environment. It is composed primarily of a simple mechanical hinged flap connected to the seabed at a depth of about 10 meters and is gravity moored. Each passing wave moves the flap, driving hydraulic pistons to deliver high pressure water via a pipeline to an onshore electrical turbine. AWS Ocean Energy – Archimedes Wave Swing™* The Archimedes Wave Swing is a seabed point-absorbing wave energy converter with a large air-filled cylinder that is submerged beneath the waves. As a wave crest approaches, the water pressure on the top of the cylinder increases and the upper part or 'floater' compresses the air within the cylinder to balance the pressures. The reverse happens as the wave trough passes and the cylinder expands. The relative movement between the floater and the fixed lower part is converted directly to electricity by means of a linear power take-off. BioPower Systems – bioWAVE™ The bioWAVE oscillating wave surge converter system is based on the swaying motion of sea plants in the presence of ocean waves. In extreme wave conditions, the device automatically ceases operation and assumes a safe position lying flat against the seabed. This eliminates exposure to extreme forces, allowing for light-weight designs. Centipod* The Centipod is a Wave Energy Conversion device currently under construction by Dehlsen Associates, LLC. It operates in water depths of 40-44m and uses a two point mooring system with four lines. Its methodology for wave energy conversion is similar to other devices. -

List of Lights Radio Aids and Fog Signals 2011

PUB. 114 LIST OF LIGHTS RADIO AIDS AND FOG SIGNALS 2011 BRITISH ISLES, ENGLISH CHANNEL AND NORTH SEA IMPORTANT THIS PUBLICATION SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE NOTICE TO MARINERS Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Bethesda, MD © COPYRIGHT 2011 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. *7642014007536* NSN 7642014007536 NGA REF. NO. LLPUB114 LIST OF LIGHTS LIMITS NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY PREFACE The 2011 edition of Pub. 114, List of Lights, Radio Aids and Fog Signals for the British Isles, English Channel and North Sea, cancels the previous edition of Pub. 114. This edition contains information available to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) up to 2 April 2011, including Notice to Mariners No. 14 of 2011. A summary of corrections subsequent to the above date will be in Section II of the Notice to Mariners which announced the issuance of this publication. In the interval between new editions, corrective information affecting this publication will be published in the Notice to Mariners and must be applied in order to keep this publication current. Nothing in the manner of presentation of information in this publication or in the arrangement of material implies endorsement or acceptance by NGA in matters affecting the status and boundaries of States and Territories. RECORD OF CORRECTIONS PUBLISHED IN WEEKLY NOTICE TO MARINERS NOTICE TO MARINERS YEAR 2011 YEAR 2012 1........ 14........ 27........ 40........ 1........ 14........ 27........ 40........ 2........ 15........ 28........ 41........ 2........ 15........ 28........ 41........ 3........ 16........ 29........ 42........ 3........ 16........ 29........ 42........ 4....... -

Gills Bay 132 Kv Environmental Statement: Volume 2: Main Report

Gills Bay 132 kV Environmental Statement: V olume 2: Main Report August 2015 Scottish Hydro Electric Transmission Plc Gills Bay 132 kV VOLUME 2 MAIN REPORT - TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Development Need 1.3 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Screening 1.4 Contents of the Environmental Statement 1.5 Structure of the Environmental Statement 1.6 The Project Team 1.7 Notifications Chapter 2 Description of Development 2.1 Introduction 2.2 The Proposed Development 2.3 Limits of Deviation 2.4 OHL Design 2.5 Underground Cable Installation 2.6 Construction and Phasing 2.7 Reinstatement 2.8 Construction Employment and Hours of Work 2.9 Construction Traffic 2.10 Construction Management 2.11 Operation and Management of the Transmission Connection Chapter 3 Environmental Impact Assessment Methodology 3.1 Summary of EIA Process 3.2 Stakeholder Consultation and Scoping 3.3 Potentially Significant Issues 3.4 Non-Significant Issues 3.5 EIA Methodology 3.6 Cumulative Assessment 3.7 EIA Good Practice Chapter 4 Route Selection and Alternatives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Development Considerations 4.3 Do-Nothing Alternative 4.4 Alternative Corridors 4.5 Alternative Routes and Conductor Support Types within the Preferred Corridor Chapter 5 Planning and Policy Context 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Development Considerations 5.3 National Policy 5.4 Regional Policy Volume 2: LT000022 Table of Contents Scottish Hydro Electric Transmission Plc Gills Bay 132 kV 5.5 Local Policy 5.6 Other Guidance 5.7 Summary Chapter 6 Landscape -

Councils in Partnership: a Local Authority Perspective on Marine Spatial Planning

Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Environmental Interactions of Marine Renewable Energy Technologies (EIMR2014), 28 April – 02 May 2014, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland. www.eimr.org EIMR2014-130 Councils in Partnership: A local authority perspective on Marine Spatial Planning Shona Turnbull1 James Green Highland Council Orkney Islands Council Glenurquhart Road, Inverness. School Place, Kirkwall. IV3 5NS KW15 1NY ABSTRACT in the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters is largely Many studies have shown that effective driven by wave and tidal energy projects. Thus, the stakeholder engagement, including local north of Scotland is an area under clear development [8] communities, is vital for the success of any marine pressure from new marine activities . This region planning project. In the UK, local authorities can is bound by Highland (Caithness and Sutherland play a vital, if often overlooked, role in building north coasts) on the mainland and the circa 70 bridges between developers, academics and local islands that are collectively known as Orkney. communities. They can facilitate knowledge Highland supports around 233,000 people, many exchange and co-operation, using their local living within a few kilometres of its 4,900 km [9] understanding of the economic, social and ecological coastline . In contrast, Orkney has a population of [10, 11] make-up of an area. Thus, Highland Council and 21,530 within its coastline of around 1,000 km . Orkney Islands Council are using a mix of As a significant local employer in the area, both the traditional terrestrial planning techniques and Highland Council and Orkney Islands Council innovative marine approaches to enable, support and understand the economic, social and ecological engage stakeholders. -

Midnight Train to Georgemas Report Final 08-12-2017

Midnight Train to Georgemas 08/12/2017 Reference number 105983 MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS IDENTIFICATION TABLE Client/Project owner HITRANS Project Midnight Train to Georgemas Study Midnight Train to Georgemas Type of document Report Date 08/12/2017 File name Midnight Train to Georgemas Report v5 Reference number 105983 Number of pages 57 APPROVAL Version Name Position Date Modifications Claire Mackay Principal Author 03/07/2017 James Consultant Jackson David Project 1 Connolly, Checked Director 24/07/2017 by Alan Director Beswick Approved David Project 24/07/2017 by Connolly Director James Principal Author 21/11/2017 Jackson Consultant Alan Modifications Director Beswick to service Checked 2 21/11/2017 costs and by Project David demand Director Connolly forecasts Approved David Project 21/11/2017 by Connolly Director James Principal Author 08/12/2017 Jackson Consultant Alan Director Beswick Checked Final client 3 08/12/2017 by Project comments David Director Connolly Approved David Project 08/12/2017 by Connolly Director TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 6 2.1 EXISTING COACH AND RAIL SERVICES 6 2.2 CALEDONIAN SLEEPER 7 2.3 CAR -BASED TRAVEL TO /FROM THE CAITHNESS /O RKNEY AREA 8 2.4 EXISTING FERRY SERVICES AND POTENTIAL CHANGES TO THESE 9 2.5 AIR SERVICES TO ORKNEY AND WICK 10 2.6 MOBILE PHONE -BASED ESTIMATES OF CURRENT TRAVEL PATTERNS 11 3. STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 14 4. PROBLEMS/ISSUES 14 4.2 CONSTRAINTS 16 4.3 RISKS : 16 5. OPPORTUNITIES 17 6. SLEEPER OPERATIONS 19 6.1 INTRODUCTION 19 6.2 SERVICE DESCRIPTION & ROUTING OPTIONS 19 6.3 MIXED TRAIN OPERATION 22 6.4 TRACTION & ROLLING STOCK OPTIONS 25 6.5 TIMETABLE PLANNING 32 7. -

Northern Isles Ferry Services

Item: 11 Development and Infrastructure Committee: 5 June 2018. Northern Isles Ferry Services. Report by Executive Director of Development and Infrastructure. 1. Purpose of Report To consider the specification for the future Northern Isles Ferry Services Contract. 2. Recommendations The Committee is invited to note: 2.1. That, in 2016, Transport Scotland appointed consultants, Peter Brett Associates, to carry out a proportionate appraisal of the Northern Isles Ferry Services, prior to drafting the future Northern Isles Ferry Services specifications. 2.2. That, as part of the appraisal process, Peter Brett Associates consulted with residents and key stakeholders, Transport Scotland, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, HITRANS, ZETRANS, Orkney Islands Council and Shetland Islands Council. 2.3. Key points from the Appraisal of Options for the Specification of the 2018 Northern Isles Ferry Services Final Report, summarised in section 4 of this report. 2.4. That, although the new Northern Isles Ferry Services contract was due to commence on 1 April 2018, the existing contract has been extended until October 2019 to consider the service specification in more detail and how the services should be procured in the future. It is recommended: 2.5. That the principles, attached as Appendix 2 to this report, be established, as the baseline position for the Council, to negotiate with the Scottish Government in respect of the contract specification for future provision of Northern Isles Ferry Services. Page 1. 2.6. That the Executive Director of Development and Infrastructure, in consultation with the Leader and Depute Leader and the Chair and Vice Chair of the Development and Infrastructure Committee, should engage with the Scottish Government, with the aim of securing the most efficient and best quality outcome for Orkney for future Northern Isles Ferry Services, by evolving the baseline principles referred to at paragraph 2.5 above. -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

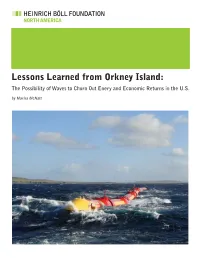

Lessons Learned from Orkney Island: the Possibility of Waves to Churn out Enery and Economic Returns in the U.S

Lessons Learned from Orkney Island: The Possibility of Waves to Churn Out Enery and Economic Returns in the U.S. by Marisa McNatt About the Author Marisa McNatt is pursuing her PhD in Environmental Studies with a renewable energy policy focus at the University of Colorado-Boulder. She earned a Master’s in Journalism and Broadcast and a Certificate in Environment, Policy, and Society from CU-Boulder in 2011. This past summer, she traveled to Europe as a Heinrich Böll Climate Media fellow with the goal of researching EU renewable energy policies, with an emphasis on marine renewables, and communicating lessons learned to U.S. policy-makers and other relevant stakeholders. Published by the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Washington, DC, March 2014 Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License Author: Marisa McNatt Design: Anna Liesa Fero Cover: ScottishPower Renewables „Wave energy device that turns energy from the waves into electricity at the European Marine Energy Center’s full-scale wave test site off the coast of Orkney Island. Pelamis P2-002 was developed by Pelamis Wave Power and is owned by ScottishPower Renewables.” Heinrich Böll Stiftung North America 1432 K Street NW Suite 500 Washington, DC 20005 United States T +1 202 462 7512 F +1 202 462 5230 E [email protected] www.us.boell.org 2 Lessons Learned from Orkney Island: The Possibility of Waves to Churn Out Enery and Economic Returns in the U.S. by Marisa McNatt A remote island off the Northern tip of Scotland, begins, including obtaining the necessary permits from long known for its waves and currents, is channeling energy and environmental regulatory agencies, as well attention from the U.S. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

A Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters

TOPIC SHEET NUMBER 12 V5 A MARINE SPATIAL PLAN FOR THE PENTLAND FIRTH AND ORKNEY WATERS 5°W 4°30’W 4°W 3°30’W 3°W 2°30’W SHETLAND PFOW Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters as per Scottish Marine Regions 59°30’N ORKNEY ORKNEY 59°00’N NORTH COAST WEST WEST 58°30’N HIGHLANDS © British Crown and SeaZone Solutions Limited. All rights reserved. Products Licence No. 122006.004 © Crown copyright and database right 2012. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100024655 MORAY 58°00’N © Crown Copyright 2012. Reproduction in whole or part is not 0 5 10 20NM permitted without prior consent of The Crown Estate. THE PLAN AREA COMBINES THE SCOTTISH MARINE REGIONS OF ORKNEY AND THE NORTH COAST Introduction Managing our marine environment is vital to integrated planning policy framework, in advance ensure our seas continue to provide sustainable of statutory regional marine planning, to guide resources, jobs and wider economic benefits. marine development, activities and management Commercial fishing, renewable energy, tourism, decisions, whilst ensuring the quality of the recreation, aquaculture, shipping, and oil and gas marine environment is protected. all contribute towards a diverse marine based economy and the Pentland Firth and Orkney The process of piloting this process resulted Waters have long been recognised as having in many lessons learned that will inform the exceptional renewable resource potential as well preparation of future regional marine plans as being of very high environmental quality. that will be developed by Marine Planning Partnerships. This will support sustainable A working group consisting of Marine Scotland, decision making on marine use and management Orkney Islands Council and Highland Council have and provide an important stepping stone towards developed a pilot Pentland Firth and Orkney the introduction of regional marine plans around Waters Marine Spatial Plan. -

Talking About Heritage

Talking about heritage Draft guidance for consultation September 2020 1 Introduction Heritage is everywhere and it means different things to different people. This guide is all about exploring and talking about heritage, so we’ve included some of the things that people have said to us when we’ve asked them, ‘What’s your heritage?’ Heritage to me is everything in Scotland’s history. It’s not just buildings but everything that’s passed down like songs, stories, myths. Perthshire ‘What’s Your Heritage’ workshop. Your heritage might be the physical places that you know and love – your favourite music venue, your local park, a ruined castle you’ve explored, or the landscapes you picture when you think of home. Your heritage could also be your working life, the stories you were told as a child, the language you speak with your family, the music or traditions you remember from an important time in your life. Heritage can inspire different emotions, both positive and negative. It can be special to people for lots of different reasons. Here are a few: • It’s beautiful. • It’s what I think of when I picture home. • It’s part of who I am • I can feel the spirits, my history. • It’s where I walk my dog. • It’s an amazing insight into my past. • It’s my home town and it reminds me of my family. Heritage can help to us to feel connected. It might be to a community, a place, or a shared past. It reflects different viewpoints across cultures and generations and is key to local distinctiveness and identity. -

Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan Report by Director of Development and Infrastructure

1 The Highland Council Agenda 9. Item Sutherland County Committee Report CC/ Caithness Committee No 16/16 30 August 2016 31 August 2016 Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan Report by Director of Development and Infrastructure Summary This report presents a summary of issues raised in comments received on the Proposed Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) and seeks approval for the Council’s response to these issues and next steps. In accordance with the Council’s Scheme of Delegation, the two Local Committees are asked to consider the report and decide on these matters. The recommended Council position is to defend the Proposed Plan, subject to only minor modifications, which would mean that the next stage would be submission to Ministers and progression to Examination. Other options would involve further consultation on a Modified Plan. The report explains the implications of each way forward. 1. Background 1.1 The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three area local development plans to be prepared by the Highland Council. Together with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and more detailed Supplementary Guidance, CaSPlan will form part of the Council’s Development Plan against which planning decisions will be made in the Caithness and Sutherland area. 1.2 The Proposed Plan consultation for CaSPlan ran from 22 January to 18 March 2016. Around 201 organisations or individuals responded, raising around 636 comments. This includes a few comments received on the associated Proposed Action Programme. All these comments have been published on the development plans consultation portal consult.highland.gov.uk.