Malayan Agricultural Journal. V12 N05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standing Advisory Committee for Medical Research in the British Caribbean

1* PAN AMERICAN HEALTH FOURTH MEETING ORGANIZATION 14-18 JUNE 1965 ADVISORY COMMITTEE WASHINGTON, D.C. ON MEDICAL RESEARCH REPORT ON THE STANDING ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN Ref: RES 4/1 15 April 1965 PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION WASHINGTON, D.C. RES 4/1 Report on THE STANDING ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN (SAC)* Origin and Development After World War I, it became the policy of the British Government to decentralize research as far as possible, and to encourage territorial governments to share with the United Kingdom in the responsibility for planning, administering and financing research. With this object regional Medical Research Councils were set up in East and West Africa. At that time all the territories concerned were colonies. The East African Council represented Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda, the West African Nigeria, Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. All these countries are now independent, and the West African Council has ceased to exist, but the East African one continues as an inter-territorial body responsible to a Council of Ministers. In the Caribbean region conditions were different; there was a much larger number of separate governmental units, all very smallcompared with those of Africa, and, with few exceptions, poor. It was felt that, at least in the early stages, it would not be reasonable to expect these territories to finance research themselves out of their slender resources. Therefore it seemed advisable as a first step to establish a committee to advise the British Government on the needs for medical research in the region, and it was hoped that later it would develop into an autonomous council with executive powers, like the councils in Africa. -

Classical Biological Control of Arthropods in Australia

Classical Biological Contents Control of Arthropods Arthropod index in Australia General index List of targets D.F. Waterhouse D.P.A. Sands CSIRo Entomology Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra 2001 Back Forward Contents Arthropod index General index List of targets The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its primary mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has special competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on the Third World. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, GPO Box 1571, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia Waterhouse, D.F. and Sands, D.P.A. 2001. Classical biological control of arthropods in Australia. ACIAR Monograph No. 77, 560 pages. ISBN 0 642 45709 3 (print) ISBN 0 642 45710 7 (electronic) Published in association with CSIRO Entomology (Canberra) and CSIRO Publishing (Melbourne) Scientific editing by Dr Mary Webb, Arawang Editorial, Canberra Design and typesetting by ClarusDesign, Canberra Printed by Brown Prior Anderson, Melbourne Cover: An ichneumonid parasitoid Megarhyssa nortoni ovipositing on a larva of sirex wood wasp, Sirex noctilio. Back Forward Contents Arthropod index General index Foreword List of targets WHEN THE CSIR Division of Economic Entomology, now Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Entomology, was established in 1928, classical biological control was given as one of its core activities. -

Macadamia Plant Protection Guide 2019-20

Macadamia protection guide 2019 plant Macadamia plant protection guide 2019–20 – 20 NSW DPI MANAGEMENT GUIDE Jeremy Bright www.dpi.nsw.gov.au PROTECT YOUR NUTS BORDEAUX WG HYDROCOP WG Protectant Fungicide/Bactericide Protectant Fungicide/Bactericide BORDEAUX WG 200g/kg COPPER (Cu) present as HYDROCOP WG 500g/kg COPPER (Cu) present as Tri-basic copper sulphate CUPRIC HYDROXIDE • Control of Husk Spot, Anthracnose, Pink limb blight • Control of Husk Spot, Anthracnose, Pink limb blight and Phytophthora stem canker and Phytophthora stem canker (Qld only) • Dry-Flowable granule for ease of mixing and • High loaded copper hydroxide formulation for lower minimal dust application rates • Superior weathering and • Dry-Flowable granule for ease sticking properties of mixing and minimal dust • Superior coverage and adhesion • Available in 15kg bags Cert. No Cert. No A6358M. due to small particle size A6358M. • Available in 10kg bags Cert. No Cert. No TRIBASICA6358M. LIQUID CROP DOCA6358M. 600 Protectant Fungicide/Bactericide Systemic Fungicide TRIBASIC LIQUID 190g/L COPPER (Cu) present as CROP DOC 600 600g/L of Phosphorous (Phosphonic) Tri-basic copper sulphate Acid present as Mono and Di Potassium Phosphite • Control of Husk spot, Anthracnose, Pink limb blight and • Control of Phytophthora root rot and Trunk (stem) Phytophthora stem canker canker (Permit PER84766) • An SC (Suspension concentrate) liquid formulation of • Formulated to be near pH neutral for increased Tribasic Copper Sulphate compatibility • Superior mixing. • Available in 20L, 200L and 1000L packs • Available in 20L, 200L and 800L packs KINGFISHER PEREGRINE Systemic Fungicide Contact and residual Insecticide 250g/L Difenoconazole 240g/L Methoxyfenozide • Control of Husk spot • Control of Macadamia flower caterpillar and • Available in 5L packs Macadamia nutborer • Suspension Concentrate • IPM compatible • Controls both eggs and early instar larvae. -

Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Fire in the Tropical World*

Proceedings: 6th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1967 Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Fire in the Tropical World* ROBERT B. BATCHELDER Department of Geograpby Boston University F IRE HAS a long history of occurrence in the tropics, and its effects upon the physical and cultural environment have been profound. For various reasons, the frequency of occur rence of accidental fires prior to man's use of fire is believed to have been low, and the area subject to devastation limited. It is known that the areal distribution of humid tropical forests during the early Pleistocene was much greater than at present. Combustibility of such forests must have been very low because of the prevailing per humid forest microclimate, and fires once ignited would have had difficulty in spreading. It may be assumed therefore, that widespread burning would occur largely in geographic areas supporting grasses and open dry forest where the occurrence of an ecological dry period of sufficient duration and intensity would permit dessi- • This paper presents part of a more complete investigation into tropical fire sponsored by the U. S. Army Natick Laboratories and reported in: Robert B. Batchelder and Howard F. Hirt, Fire in Tropical Forests and Grasslands, Technical Report 67-41-ES, U. S. Army Natick Laboratories, Natick, Mass. June 1966, 380 pp. 171 Proceedings: 6th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1967 ROBERT B. BATCHELDER cation of available fuels. It must be remembered, however, that Pleistocene grass and brush lands were much less extensive than at present and probably occurred as enclaves in the extensive dense forest. -

Downloaded From

B. Richardson Depression riots and the calling of the 1897 West India Royal Commission Questions why the West India Royal Commission of 1897 was considered necessary when serious distress already existed in the 1880s. Author argues that riots caught the government's attention much more readily than statistical data. Even minor disturbances could have distracted London from its preoccupation with the newer, more important parts of the Empire. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 66 (1992), no: 3/4, Leiden, 169-191 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:13:11AM via free access BONHAM C. RICHARDSON DEPRESSION RIOTS AND THE CALLING OF THE 1897 WEST INDIA ROYAL COMMISSION Within the vastness of primary archival material that the British generated in describing, measuring, and administering their Caribbean colonies, few documents are so useful as those associated with Royal Commissions of Inquiry. The commissions themselves, of course, were aperiodic, problem- oriented phenomena, and they provided particularly important documen- tary records of the region in the period immediately prior to and following emancipation. Especially in the mid- to late-nineteenth century in the British Caribbean, when planters and freedmen were coming to grips with new social and economie arrangements in an environment clouded with old animosities, a number of commissions dealt with such issues as sugar cane production, labor immigration, financial issues, and social disturbances (Williams 1970:535-37). Commissioners were usually, though not always, sent from Britain to assess local problems. These problems or issues, fur- ther, were usually confined to a particular event, theme, or island, although the commissions on rare occasion were asked to survey the entire region. -

Biology of Coconut Moth, Batrachedra Arenosella Walker (Lepidoptera : Batrachedridae) on Immature Nuts of Coconut in India

J. Exp. Zool. India Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 353-356, 2018 www.connectjournals.com/jez ISSN 0972-0030 BIOLOGY OF COCONUT MOTH, BATRACHEDRA ARENOSELLA WALKER (LEPIDOPTERA : BATRACHEDRIDAE) ON IMMATURE NUTS OF COCONUT IN INDIA C. Prashantha1#*, T. Shivashakar2 and A. K. Chakravarthy3 1Department of Agricultural Entomology, UAS, GKVK, Bengaluru - 560 065, India. 2College of Agriculture, Mandya, India. 3Division of Entomology and Nematology, Indian Institute of Horticultural Research, Bengaluru - 560 089, India. *e-mail: [email protected] (Accepted 19 October 2017) ABSTRACT : Larvae of coconut moth, Batrachedra arenosella Walker (Lepidoptera : Batrachedridae) were found damaging premature nuts of coconut for the first time in India. The feeding resulted on an average of 20% loss of nuts in Mysore and Mandya districts of Karnataka, South India. The mean egg incubation period was 2.95 ± 0.55 days. Larval stage comprised four instars and the mean duration of first, second, third and fourth instar larvae were 2.55 ±2.50, 2.75 ± 0.35, 3.40 ± 0.57 and 4.10 ± 0.61 days, respectively. Total larval period varied from 11 to 14 days, with an average of 12.80 ± 1.01 days. Mean pupal period was 7.20 ± 0.86 days. The total developmental period occupied 22.95 ±1.17 days. Adult females lived longer (6.50 ± 1.20 days) than males (5.50 ± 0.78 days). The study indicated that B. arenosella has more than one generation a year. Short life cycle, presence of adults and larvae throughout the year in an overlapping manner and a perennial host characterizes B. arenosella to be an economically important pest. -

Biological Control of the Coconut Moth, Batrachedra Arenosella by Chelonus Parasites in Indonesia1

Vol. 27, December 15,1986 41 Biological Control of the Coconut Moth, Batrachedra arenosella by Chelonus Parasites in Indonesia1 WILY ARDERT BARINGBING2 ABSTRACT An experiment was conducted on the island of Flora, Indonesia, to test for biological control of the coconut moth, Batrachedra arenosella Walker, by introducing the braconid parasite Chelonus sp. Six and twelve months after releasing S gravid females of Chelonus per 4 ha of moth-infested coconuts, the per centage infection of the host pupae, the distribution capacity and the population density of the parasites were determined at 0,50 and 100 m from the point of release. The results of the experiment show that the percentage of parasitized host pupae and population density of the parasite 0 and SO m from the point of release were approximately twice that found at 100 m. This suggests a slow outward spread of the para site from its point of introduction. There were only slight increases after 12 months in these parameters and in the percentage of spathes where Chelonus was found when compared with results after 6 months. These results suggest that the parasite has become established but spreads out slowly from its point of introduction. There was only a slight reduction in pest population following release of the parasite during the 12-month period. The coconut moth, Batrachedra arenosella Walker, (Lepidoptera; Cosmoptery- gidae) is a serious pest of coconut palm (Cocos nucifera L.) in Indonesia (Tjoa, 1953; Kalshoven, 1981). Larvae of the moth cause extensive damage to coconuts, feeding on the male and female flowers in unopened spathes. -

Short-Range Prospects in the British Caribbean.” Author(S): M.G

Retrieved from: http://www.cifas.us/smith/journals.html Title: “Short-range prospects in the British Caribbean.” Author(s): M.G. Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies 11 (4): 392-408. Reprinted in The Plural Society in the British West Indies, p. 304-321. Partially reprinted in Readings in Government and Politics of the West Indies. A. W. Singham et al, comps. Kingston, Jamaica: n.p., n.d. p. 390-398. i SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STUDIES VOL. 11, NO.4, DECEMBER. 1962 SPECIAL NUMBER on THE CONFERENCE ON POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY l IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN, DECEMBER, 1961 PART I Jesse H. Proctor 273 British West Indian Society and GovernOlent in Transition, 1920-1960 Douglas Hall 305 Slaves and Slavery in the British West Indies G. E. Cumper 319 The Differentiation of Economic Groups in the West Indies G. W. Roberts 333 Prospects for Population Growth in the \Vest Indies PART II K. E. Boulding 351 The Relations of Economic, Political and Social Systems David Lowenthal 363 Levels of West Indian Governnlent M. G. Smith 392 Short-R.~~~~_~r.~~P~~.~sin the British Carib Dean Wendell Bell 409 Ec}'lUJIty and Attitudes of Elites in Jamaica Vera Rubin 433 Culture, Politics and Race Relations INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES, JAMAICA. .. Short-range Prospects in the British Caribbeana By M. G. SMITH Projections Prediction is not the favourite pastime of social scientists. It can be risky business, even for journalists. When unavoidable, one favourite solution is to develop oracular statements, cryptic or general enough to rule out dis proof. -

Download Articles

QL 541 .1866 ENT The Journal of Research Lepidoptera Volume 46 2013 ISSN 0022 4324 (PRINT) 2156 5457 (ONLINE) THE LEPIDOPTERA RESEARCH FOUNDATION The Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera www.lepidopteraresearchfoundation.org ISSN 0022 4324 (print) 2156 5457 (online) Published by: The Lepidoptera Research Foundation, Inc. 9620 Heather Road Beverly Hills, California 90210-1757 TEL (310) 274 1052 E-mail: Editorial: [email protected] Technical: [email protected] Founder: William Hovanitz (1915-1977) Editorial Staff: Konrad Fiedler, University of Vienna, Editor [email protected] Nancy R. Vannucci, info manager [email protected] Associate Editors: Annette Aiello, Smithsonian Institution [email protected] Joaquin Baixeras, Universitat de Valencia [email protected] Marcelo Duarte, Universidade de Sao Paulo [email protected] Klaus Fischer, University of Greifswald [email protected] Krushnamegh Kunte, Natl. Center for Biol. Sci, India [email protected] Gerardo Lamas, Universidad Mayor de San Marcos [email protected]. pe Rudi Mattoni [email protected] Soren Nylin, Stockholm University [email protected] Naomi Pierce, Harvard University [email protected] Robert Robbins, Smithsonian Institution [email protected] Daniel Rubinoff, University of Hawaii [email protected] Josef Settele, Helmholtz Cntr. for Environ. Research-UFZ [email protected] Arthur M. Shapiro, University of California - Davis [email protected] Felix Sperling, University of Alberta [email protected] Niklas Wahlberg, University of Turku [email protected] Shen Horn Yen, National Sun Yat-Sen University [email protected] Manuscripts and notices material must be sent to the editor, Konrad Fiedler [email protected]. -

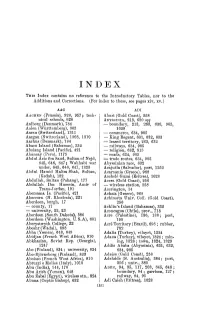

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

Insect Pests and Insect-Vectored Diseases of Palmsaen 724 328..342

Australian Journal of Entomology (2009) 48, 328–342 Insect pests and insect-vectored diseases of palmsaen_724 328..342 Catherine W Gitau,1* Geoff M Gurr,1 Charles F Dewhurst,2 Murray J Fletcher3 and Andrew Mitchell4 1EH Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation, Charles Sturt University, PO Box 883 Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. 2PNG Oil Palm Research Association, Kimbe, West New Britain, Papua New Guinea. 3NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange Agricultural Institute, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. 4NSW Department of Primary Industries, Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2650, Australia. Abstract Palm production faces serious challenges ranging from diseases to damage by insect pests, all of which may reduce productivity by as much as 30%. A number of disorders of unknown aetiology but associated with insects are now recognised. Management practices that ensure the sustainability of palm production systems require a sound understanding of the interactions between biological systems and palms. This paper discusses insect pests that attack palms, pathogens the insects vector as well as other disorders that are associated with these pests. We re-examine the disease aetiologies and procedures that have been used to understand causality. Pest management approaches such as cultural and biological control are discussed. Key words aetiology, Arecaceae, diagnosis, pathosystems, pest management. INTRODUCTION has transported them from their native habitats to new loca- tions. For example, the date palm is believed to have originated In many cultures, palms are a symbol of splendour, peace, in the Persian Gulf and North Africa but it is now grown victory and fertility. Palms constitute one of the best-known worldwide in semi-arid regions (Zaid 1999). -

Contacts & References

Papaw information kit Reprint – information current in 2000 REPRINT INFORMATION – PLEASE READ! For updated information please call 13 25 23 or visit the website www.dpi.qld.gov.au This publication has been reprinted as a digital book without any changes to the content published in 2000. We advise readers to take particular note of the areas most likely to be out-of-date and so requiring further research: • Chemical recommendations—check with an agronomist or Infopest www.infopest.qld.gov.au • Financial information—costs and returns listed in this publication are out of date. Please contact an adviser or industry body to assist with identifying more current figures. • Varieties—new varieties are likely to be available and some older varieties may no longer be recommended. Check with an agronomist, call the Business Information Centre on 13 25 23, visit our website www.dpi.qld. gov.au or contact the industry body. • Contacts—many of the contact details may have changed and there could be several new contacts available. The industry organisation may be able to assist you to find the information or services you require. • Organisation names—most government agencies referred to in this publication have had name changes. Contact the Business Information Centre on 13 25 23 or the industry organisation to find out the current name and contact details for these agencies. • Additional information—many other sources of information are now available for each crop. Contact an agronomist, Business Information Centre on 13 25 23 or the industry organisation for other suggested reading. Even with these limitations we believe this information kit provides important and valuable information for intending and existing growers.