Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standing Advisory Committee for Medical Research in the British Caribbean

1* PAN AMERICAN HEALTH FOURTH MEETING ORGANIZATION 14-18 JUNE 1965 ADVISORY COMMITTEE WASHINGTON, D.C. ON MEDICAL RESEARCH REPORT ON THE STANDING ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN Ref: RES 4/1 15 April 1965 PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION WASHINGTON, D.C. RES 4/1 Report on THE STANDING ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN (SAC)* Origin and Development After World War I, it became the policy of the British Government to decentralize research as far as possible, and to encourage territorial governments to share with the United Kingdom in the responsibility for planning, administering and financing research. With this object regional Medical Research Councils were set up in East and West Africa. At that time all the territories concerned were colonies. The East African Council represented Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda, the West African Nigeria, Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. All these countries are now independent, and the West African Council has ceased to exist, but the East African one continues as an inter-territorial body responsible to a Council of Ministers. In the Caribbean region conditions were different; there was a much larger number of separate governmental units, all very smallcompared with those of Africa, and, with few exceptions, poor. It was felt that, at least in the early stages, it would not be reasonable to expect these territories to finance research themselves out of their slender resources. Therefore it seemed advisable as a first step to establish a committee to advise the British Government on the needs for medical research in the region, and it was hoped that later it would develop into an autonomous council with executive powers, like the councils in Africa. -

Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Fire in the Tropical World*

Proceedings: 6th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1967 Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Fire in the Tropical World* ROBERT B. BATCHELDER Department of Geograpby Boston University F IRE HAS a long history of occurrence in the tropics, and its effects upon the physical and cultural environment have been profound. For various reasons, the frequency of occur rence of accidental fires prior to man's use of fire is believed to have been low, and the area subject to devastation limited. It is known that the areal distribution of humid tropical forests during the early Pleistocene was much greater than at present. Combustibility of such forests must have been very low because of the prevailing per humid forest microclimate, and fires once ignited would have had difficulty in spreading. It may be assumed therefore, that widespread burning would occur largely in geographic areas supporting grasses and open dry forest where the occurrence of an ecological dry period of sufficient duration and intensity would permit dessi- • This paper presents part of a more complete investigation into tropical fire sponsored by the U. S. Army Natick Laboratories and reported in: Robert B. Batchelder and Howard F. Hirt, Fire in Tropical Forests and Grasslands, Technical Report 67-41-ES, U. S. Army Natick Laboratories, Natick, Mass. June 1966, 380 pp. 171 Proceedings: 6th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1967 ROBERT B. BATCHELDER cation of available fuels. It must be remembered, however, that Pleistocene grass and brush lands were much less extensive than at present and probably occurred as enclaves in the extensive dense forest. -

Short-Range Prospects in the British Caribbean.” Author(S): M.G

Retrieved from: http://www.cifas.us/smith/journals.html Title: “Short-range prospects in the British Caribbean.” Author(s): M.G. Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies 11 (4): 392-408. Reprinted in The Plural Society in the British West Indies, p. 304-321. Partially reprinted in Readings in Government and Politics of the West Indies. A. W. Singham et al, comps. Kingston, Jamaica: n.p., n.d. p. 390-398. i SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STUDIES VOL. 11, NO.4, DECEMBER. 1962 SPECIAL NUMBER on THE CONFERENCE ON POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY l IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN, DECEMBER, 1961 PART I Jesse H. Proctor 273 British West Indian Society and GovernOlent in Transition, 1920-1960 Douglas Hall 305 Slaves and Slavery in the British West Indies G. E. Cumper 319 The Differentiation of Economic Groups in the West Indies G. W. Roberts 333 Prospects for Population Growth in the \Vest Indies PART II K. E. Boulding 351 The Relations of Economic, Political and Social Systems David Lowenthal 363 Levels of West Indian Governnlent M. G. Smith 392 Short-R.~~~~_~r.~~P~~.~sin the British Carib Dean Wendell Bell 409 Ec}'lUJIty and Attitudes of Elites in Jamaica Vera Rubin 433 Culture, Politics and Race Relations INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES, JAMAICA. .. Short-range Prospects in the British Caribbeana By M. G. SMITH Projections Prediction is not the favourite pastime of social scientists. It can be risky business, even for journalists. When unavoidable, one favourite solution is to develop oracular statements, cryptic or general enough to rule out dis proof. -

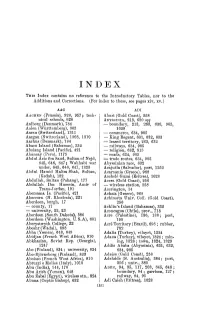

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

An Archaeological and Historical Study of Guana Island, British Virgin Islands

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects Summer 2018 On The Margins of Empire: An Archaeological and Historical Study of Guana Island, British Virgin Islands Mark Kostro College of William and Mary - Arts & Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Kostro, Mark, "On The Margins of Empire: An Archaeological and Historical Study of Guana Island, British Virgin Islands" (2018). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1530192807. http://dx.doi.org/10.21220/s2-0wy4-3r12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On the Margins of Empire: An archaeological and historical study of Guana Island, British Virgin Islands. Mark Kostro Williamsburg, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William & Mary, 2003 Bachelor of Arts, Rutgers University, 1996 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of The College of William & Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of William & Mary May 2018 © Copyright by Mark Kostro 2018 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by the Committee, March 2018 �or=--:: Arts and Sciences Distingu ed Professor Audrey Horning, Anthropology Col ege of William & Mary National Endowment for the Humanities(/{; Pr Micha I-Blakey, Anthropology e of William & Mary ssor Neil Norman, Anthropology College of William & Mary Ass!!d:..f J H:il. -

The Transition from Slavery to Other Forms of Labor in the British Caribbean, Ca

M. Craton Reshuffling the pack : the transition from slavery to other forms of labor in the British Caribbean, ca. 1790-1890 Analysis of a century of (evolutionary) socio-economic transition in the British Caribbean. According to the author, this process demonstrated aspects of a continuum, rather than sharply marked phases and abrupt changes. Before the abolition of slavery slaves behaved as proto- peasants and proto-proletarians and many aspects of slavery survived the abolition. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 68 (1994), no: 1/2, Leiden, 23-75 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 12:54:31PM via free access MlCHAEL J. CRATON RESHUFFLING THE PACK: THE TRANSITION FROM SLAVERY TO OTHER FORMS OF LABOR IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN, CA. 1790-1890' PROLOGUE The separate and rival imperialisms of the mercantilist era gave the First British Empire a distinctive functional identity, and the British system passed through successive stages of commercial and industrial capitalism in advance of others. Yet there is an artificiality in separating the transition out of a slave labor system within the British colonies from later processes else- where, and this is made all the more unacceptable by the general decay of mercantilism, the progressive spread of free trade and laissez faire princi- ples, and the concurrent substitution of a world-wide and intensifying cap- italist system. The British slave trade from Africa was ended in 1808 and British slaves were formally freed in 1838, whereas both the trade and the institution of slavery lingered on in other imperial systems. -

Ask Most Casual Students of History When the Time of Colonialism Came to an End

ABSTRACT Guiana and the Shadows of Empire: Colonial and Cultural Negotiations at the Edge of the World Joshua R. Hyles, M.A. Mentor: Keith A. Francis, Ph.D. Nowhere in the world can objective study of colonialism and its effects be more fruitful than in the Guianas, the region of three small states in northeastern South America. The purpose of this thesis is threefold. First, the history of these three Guianas, now known as Guyana, French Guiana, and Suriname, is considered briefly, emphasizing their similarities and regional homogeny when compared to other areas. Second, the study considers the administrative policies of each of the country’s colonizers, Britain, France, and the Netherlands, over the period from settlement to independence. Last, the thesis concentrates on current political and cultural situations in each country, linking these developments to the policies of imperial administrators in the previous decades. By doing so, this thesis hopes to show how an area that should have developed as a single polity could become a region of three very distinct cultures through the altering effects of colonialism. Guiana and the Shadows of Empire: Colonial and Cultural Negotiations at the Edge of the World by Joshua R. Hyles, A.S., B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Keith A. Francis, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ David L. Longfellow, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Thomas A. -

Annex B – Territories Forming Part of the Commonwealth

ANNEX B TERRITORIES FORMING PART OF THE COMMONWEALTH Members of the Commonwealth Date of Membership United Kingdom 1931 (Statute of Westminster) United Kingdom Dependent Territories Crown Dependencies: Channel Islands Isle of Mani United Kingdom Dependent Territories Colonies: Anguilla Bermuda British Antarctic Territory British Indian Ocean Territory British Virgin Islands Cayman Islands Falkland Islands and Dependencies Gibraltar Montserrat Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands St Helena and Dependencies (principally Ascension and Tristan da Cunha) Turks and Caicos Islands The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekeliaii Antigua and Barbuda 1981 Australia 1931 (Statute of Westminster) Australian External Territories: Australian Antarctic Territory (including MacDonald, Heard and Macquarie Islands) Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Norfold Island The Bahamas 1973 Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) 1972 Barbados 1966 Belize (formerly British Honduras) 1981 Botswana (formerly Bechuanaland 1966 Protectorate) Brunei Darussalam 1984 Cameroon 1995 Canada 1931 (Statute of Westminster) Cyprus 1961 Dominica 1978 Fiji Islandsiii 1997 The Gambia 1965 Ghana (comprising the former colony of 1957 the Gold Coast (including Ashanti), the former Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (a Protectorate), the former Togoland (a UK Trust Territory). Grenada 1974 Guyana (formerly British Guiana) 1966 India 1947 Jamaica 1962 Kenya 1963 Kiribati (formerly Gilbert Islands) 1979 Lesotho (formerly Basutoland) 1966 Malawi (formerly Nyasaland) 1964 -

British Guiana – British Empire Exhibition, Wembley 1924

British Guiana – British Empire Exhibition, Wembley 1924 BRITISH GUIANA BRITISH EMPIRE EXHIBITION WEMBLEY 1924 CONTENTS 1 British Guiana – British Empire Exhibition, Wembley 1924 INTRODUCTION GEOGRAPHY KAIETEUR FALLS POPULATION Aborigines Immigration Centres of Population FAUNA FLORA TIMBER AND FOREST INDUSTRIES SUGAR, R ICE AND AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRIES MINING INDUSTRIES COMMERCE AND SHIPPING Communications OPPORTUNITIES FOR CAPITAL 2 British Guiana – British Empire Exhibition, Wembley 1924 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Note: Click here to view these photos Kaieteur Falls, Potaro River A Locust Tree (Hymencea courbaril) A Road in the Interior, 150 miles Heading out Sugar Canes to Punts from Georgetown Potato River, on the way to Steam Hoist Lifting Canes at a Kaieteur Falls Sugar Factory Brink of Kaieteur Falls Loading the Cut Cane into Punts on a Sugar Estate In the Gorge below Kaieteur Falls; Ploughing a Rice Field looking down river Amatuk Rest House, Potaro River, Harvesting the Rice on the way to Kaieteur Falls Gold Digging Camp at foot of A Coconut Plantation Eagle Mountain Wismar, 65 miles up Demerara Indian Girl Spinning Cotton River Kanaka Mountains and Interior The Rupununi Cattle Trail, Bridge Savannas Over a Creek Aboriginal Indians Travelling by Steer Bred on Rupununi Savanna Corial Indian Shooting Fish Rupununi River, looking North to the Kanaka Mountains The Public Buildings, Georgetown Alluvial Gold Mining Main Street, Georgetown, and the Cattle on the Rupununi Savannas War Memorial 3 British Guiana – British Empire Exhibition, -

International Schedule of Territories

IFTA® INTERNATIONAL SCHEDULE OF TERRITORIES IMPORTANT: The following IFTA® Schedule of Territories outlines individual countries, groups of countries and territories, and groups of territories as they are often used for purposes of granting distribution rights for films or television programs. When referenced in the Deal Terms of the IFTA® International Multiple Rights Agreement, the Schedule is incorporated by reference. However, the Schedule may not be appropriate for all media due to the method of distribution. The Schedule is organized in the following three ways: 1) Alphabetical Listing, 2) Geographical Listing, and 3) Language Group Listing. Users should note that the terms in bold refer to and are comprised of all the countries, territories and/or islands listed in the succeeding definition. Users should also note that some of the definitions overlap. The information appearing in this Schedule is based on the most current information available as of the publication date of this Version 2018. IFTA does not assume legal responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information in this Schedule. This is not intended to and cannot replace the need to consult legal counsel. These definitions are subject to change as developments in national boundaries occur. IFTA reserves the right in its sole discretion to change the following definitions at any time as conditions may require. ALPHABETICAL LISTING Africa – Algeria; Angola; Benin (Dahomey); Botswana; Burkina Faso (Upper Volta); Burundi; Cameroon; Cape Verde Islands; Central -

List of Sources

List of Sources General Bolivia La Paz, Altmir, 0., The Extent of Poverty in Latin America. Bird Working Anuario Geografico. Estadistico de La Republica de Bolivia. Paper 522, Washington, 1982. 1988. Blackmore, H.&: Smith, C.T. Latin America. London, Methuen, 1983. Area Handbook Series: Bolivia - A Country Study. The American Bulterworth, D., Latin American Urbanization. Cambridge, Cambridge University, Washington D.C. University Press, 1981. Dummerley, J., Rebellion in the Veins, Political Struggle in Bolivia Butland, G.J., Latin America. John Witey &: Son. N.Y., 1966. I95I-I982. Verso, 1984. Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook I990. Washington Fifer, J.V., Bolivia: Land, Location and Politics Since I825. California D.C. University Press, 1972. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., I987 Britannica World Data. Chicago, Chile 1987. Anuario Estadistico. lnstituto Nacional de Estadistica. Santiago, 1988. Economic Relations between Europe and Gleich, A., The Political and Area Handbook Series: Chile - A Country Study. The American 1983. Latin America. I.E.I. Hamburg, Universtiy. Washington D.C. Oxford, 1990. Heinemann Educational, Geographical Digest I990-9I. Militar, Atlas Geografico de Chile, para Ia Agostini I990. lnstituto Geogratico lnstituto Geografico de Agostini, Calendario At/ante De Educacion. Santiago, 1985. Novara, 1989. T.X., &: Alvarado, E.Z., Geografia de Chile, Editoria 1969. Olivares, Jones, Preston E., Latin America. 3rd Ed. London, Cassel, Universitaria, 1984. Lambert, D.C., Ameriques Latines. Declins et Decollages, Ed. Economica, Paris, 1984. Argentina Morris, A.S., Latin America Economic Development and Regional Area Handbook Series: Argentina - A Country Study. The American Differentiation. Totowa, N.J., Barnes and Noble, 1981. University, Washington D.C. Morris, A., South America. -

British Decolonization in the Caribbean

BRITISH DECOLONIZATION IN THE CARIBBEAN: THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION By SHARON C. SEWELL Bachelor of Arts Bridgewater State College Bridgewater, Massachusetts 1978 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS July, 1997 BRITISH DECOLONIZATION IN THE CARIBBEAN: THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION Thesis Approved: --- o Thesis Adviser Dean of the Graduate College 11 PREFACE In 1947 Great Britain together its Caribbean colonies to discuss the idea of a closer association among them. The British wanted the colonies to Wlite in a federation to which Britain would give independence and entry into the Commonwealth. After World War II it was an accepted view among the larger countries that small nations could not compete economically and survive politically in the modem world. Britain's belief in this theory led them to their offer of 1947. However, in their efforts to rid themselves of their economically poor colonies in the Caribbean, the British failed to take into consideration the insularity they had fostered for years in the area. Although Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, the Leeward Islands of Antigua, Montserrat, and St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, and the Windward Islands of Dominica, Grenada, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent shared much in common, including their agriculture-based economy and their British heritage, they had lived independently of each other for centuries. Although they agreed to explore the possibility of federation, and even embarked on the venture for four short years, their reluctance to give up their new-found political freedom brought about the collapse of their federation.