River of Firecommons, Crisis & the Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Ascap Songwriters in the Top 50 of the Country Aircheck

Peak Position Peak Wks. on 2020 Artist Title Label (wks. at No.1) Date Chart Rank JASON ALDEAN We Back Macon Music/Broken Bow 6 3/23/20 21 43 JASON ALDEAN Got What I Got Macon Music/Broken Bow 1(1) 10/19/20 29 33 A JIMMIE ALLEN Make Me Want To Stoney Creek 1(1) 3/2/20 18 28 s INGRID ANDRESS More Hearts Than Mine Warner/WEA 1(1) 4/27/20 26 24 of TOP 15 KELSEA BALLERINI Hole In The Bottle Black River 13 11/9/20 19 75 GABBY BARRETT I Hope Warner/WAR 1(1) 4/20/20 25 3 LEE BRICE One Of Them Girls Curb 1(2) 10/5/20 26 32 GARTH BROOKS & BLAKE SHELTON Dive Bar Pearl 5 3/2/20 17 56 B KANE BROWN Homesick RCA 1(2) 3/16/20 20 17 KANE BROWN Cool Again RCA 2 9/28/20 25 37 LUKE BRYAN What She Wants Tonight Capitol 1(1) 3/30/20 22 30 2020 LUKE BRYAN One Margarita Capitol 1(2) 7/13/20 15 22 theYEAR KENNY CHESNEY Tip Of My Tongue Blue Chair/Warner/WEA 7 11/18/19 8 74 CARLY PEARCE in MUSIC KENNY CHESNEY Here And Now Blue Chair/Warner/WEA 1(1) 6/29/20 21 36 CMA Musical Event of the Year (“I Hope You’re Happy Now”) KENNY CHESNEY Happy Does Blue Chair/Warner/WEA 11 11/9/20 16 64 ERIC CHURCH Monsters EMI Nashville 15 5/4/20 30 55 C LUKE COMBS Even Though I’m Leaving River House/Columbia 1(3) 12/2/19 9 5 LUKE COMBS f/ERIC CHURCH Does To Me River House/Columbia 1(2) 6/1/20 20 11 DAN + SHAY & JUSTIN BIEBER LUKE COMBS Lovin’ On You River House/Columbia 1(2) 9/21/20 16 38 JAMIE MOORE & CRAIG WISEMAN 3x AMA Winners LUKE COMBS Better Together River House/Columbia 15 11/9/20 5 -- Aircheck #1 Country Song of the Year Favorite Song/Collab of the Year (“10,000 Hours”) -

“The Savage Harmony”. Wallace Stevens and the Poetic Apprehension of an Anthropic Universe

“BABEŞ-BOLYAI” UNIVERSITY OF CLUJ-NAPOCA FACULTY OF LETTERS “THE SAVAGE HARMONY”. WALLACE STEVENS AND THE POETIC APPREHENSION OF AN ANTHROPIC UNIVERSE — SUMMARY — Scientific advisor: Virgil Stanciu, Ph.D. Doctoral candidate: Octavian-Paul More Cluj-Napoca 2010 Contents: Introduction: Stevens, the “Savage Harmony” and the Need for Revaluation Chapter I: Between “Ideas about the Thing” and “The Thing Itself”—Modernism, Positioning, and the Subject – Object Dialectic 1.1. Universalism, the search for the object and the metaphor of positioning as a “root metaphor” in Modernist poetry 1.2. “In-betweenness,” “coalescence” and the relational nature of Modernism 1.3. Common denominators and individual differences in redefining the Modernist search for the object 1.3.1. The drive toward identification, “subjectivising” the object and the “poetry of approach” (W. C. Williams) 1.3.2. Detachment, anti-perspectivism and the strategy of the “snow man” (W. Stevens) 1.4. Universalism revisited: the search for the object as a new mode of knowledge 1.4.1. The shift from static to dynamic and the abstractisation/reification of vision 1.4.2. Relativism vs. indetermination and the reassessment of the position of the subject 1.5. Individual vs. universal in a world of fragments: the search for the object as an experience of locality 1.5.1. “The affair of the possible” or “place” as the changing parlance of the imagination (W. Stevens) 1.5.2. “Suppressed complex(es)” or “place” as the locus of dissociation and transgression (T. S. Eliot) 1.5.3. “The palpable Elysium” or “place” as recuperation and reintegration (E. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS NOVEMBER 9, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 17 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Russell Dickerson ASCAP, BMI, SESAC Country Extends Streak >page 4 Winners Reflect On Their Jobs’ Value CMA Battles COVID-19 Successful country songwriters know how to embed their songs song of the year victor for co-writing the Luke Combs hit “Even >page 9 with just the right amount of repetition. Though I’m Leaving.” Old Dominion’s “One Man Band” took The performing rights organizations set the top of their 2020 the ASCAP country song trophy for three of the group’s mem- winners’ lists to repeat as the ASCAP, BMI and SESAC country bers — Trevor Rosen, Brad Tursi and Matthew Ramsey, who songwriter and publisher of the year awards all went to enti- previously earned the ASCAP songwriter-artist trophy in 2017 Christmas With ties who have pre- — plus songwriter The Oaks, LeVox, viously taken top Josh Osborne, Dan + Shay honors. A shley who adds the title >page 10 Gorley (“Catch,” to two song of the “Living”) hooked year winners he ASCAP’s song- co-wrote with Sam writer medallion Hunt: 2018 cham- Trebek Leaves Some for the eighth time, pion “Body Like a Trivia In His Wake and for the sev- Back Road” and >page 10 enth year in a row, 2015 victor “Leave when victors were the Night On.” unveiled Nov. 9. Even Ben Bur- Makin’ Tracks: Ross Copperman gess, who won Michael Ray’s (“What She Wants his first-ever BMI Tonight,” “Love award with “Whis- ‘Whiskey And Rain’ COPPERMAN GORLEY McGINN >page 14 Someone”) swiped key Glasses,” BMI’s songwriter cruised to the PRO’s title for the fourth time on Nov. -

Child Development: Day Care. 8. Serving Children with Special Needs

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 185 PS 005 949 AUTHOR Granato, Sam; Krone, Elizabeth TITLE Child Development: Day Care. 8. Serving Children with Special Needs. INSTITUTION Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (DHEW/OE), Washington, D.C.; Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Washington, D.C. Secretary's Committee on Mental Retardation.; Office of Child Development (DHEW), Washington, D.C.; President's Committee on Mental Retardation, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO DHEW-OCD-72-42 PUB DATE 72 NOTE 74p. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Stock Number 1791-0176, $0.75) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; *Child Care Workers; *Child Development; Community Resources; *Day Care Programs; Deaf Children; Emotionally Disturbed; Financial Support; Guides; *Handicapped Children; Mentally Handicapped; Parent Participation; Physically Handicapped; Program Planning; *Special Services; Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT This handbook defines children with special needs and develops guidelines for providing services to them. It answers questions commonly raised by staff and describes staff needs, training, and resources. It discusses problems related to communicating with parents, questions parents ask, parents of special children, and communication between parents. It provides guidelines for program development including basic needs for all children, orientation activities, promoting good feelings among children, designing behavior, daily activities, dealing with difficult -

Volume 6 - Issue 9 - June, 1897 Rose Technic Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar Technic Student Newspaper Summer 6-1897 Volume 6 - Issue 9 - June, 1897 Rose Technic Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/technic Recommended Citation Staff, Rose Technic, "Volume 6 - Issue 9 - June, 1897" (1897). Technic. 199. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/technic/199 Disclaimer: Archived issues of the Rose-Hulman yearbook, which were compiled by students, may contain stereotyped, insensitive or inappropriate content, such as images, that reflected prejudicial attitudes of their day--attitudes that should not have been acceptable then, and which would be widely condemned by today's standards. Rose-Hulman is presenting the yearbooks as originally published because they are an archival record of a point in time. To remove offensive material now would, in essence, sanitize history by erasing the stereotypes and prejudices from historical record as if they never existed. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technic by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROSE TECHNIC. VOL. VI. Terre'Haute, Ind., June, 1897. No. 9. THE TECHNIC. that we extend our most sincere thanks to both subscribers and contributors for their aid in mak- BOARD OF EDITORS: ing TIIE TECHNIC a possibility. We greatly ap- ' Editor in Chief. preciate the support we have received from the J. H. HALL. faculty, the alumni and the students, as well as Associate Editors. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

April 12, 2021

APRIL 12, 2021 APRIL 12, 2021 Tab le o f Contents 4 #1 Songs This Week 6 powers 7 action/ recurrents 9 hotzone / developing 11 pro-file 14 video streaming 15 country callout 16 future tracks 17 intelescope 18 intelevision 19 methodolgy 20 the back page Songs this week #1 BY MMI COMPOSITE CATEGORIES 4.12.21 ai r p lay FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE “Long Live” retenTion TENILLE ARTS“Somebody Like That” callout BRETT YOUNG“Lady” audio CHRIS STAPLETON“Starting Over” VIDEO LUKE COMBS“Forever After All” SALES GABBY BARRETT“The Good Ones” COMPOSITE GABBY BARRETT“The Good Ones” MondayMorningIntel.com CLICK HERE to E-MAIL Monday Morning Intel with your thoughts, suggestions, or ideas. mmi-powers 4.12.21 Weighted Airplay, Retention Scores, Streaming Scores, and Sales Scores this week combined and equally weighted deviser Powers Rankers. TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW COMP AIRPLAY RETENTION CALLOUT AUDIO VIDEO SALES RANK ARTIST TITLE LABEL 4 9 6 2 3 1 1 GABBY BARRETT The Good Ones Warner/WAR 2 8 4 4 13 4 2 THOMAS RHETT What’s Your Country Song Valory 3 6 31 1 2 3 3 CHRIS STAPLETON Starting Over Mercury Nashville 5 13 1 10 4 7 4 BRETT YOUNG Lady BMLG 19 x 17 3 1 2 5 LUKE COMBS Forever After All River House/Columbia Nash 1 3 2 5 31 16 6 FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE Long Live BMLG 7 2 16 9 19 24 7 DUSTIN LYNCH Momma’s House Broken Bow 11 10 24 6 14 8 8 ERIC CHURCH Hell Of A View EMI Nashville 8 5 8 23 29 10 9 JAKE OWEN Made For You Big Loud 20 15 13 14 9 9 10 KEITH URBAN WITH P!NK One Too Many RCA/Capitol Nashville 12 20 7 12 11 13 11 SAM HUNT Breaking Up Was Easy In The.. -

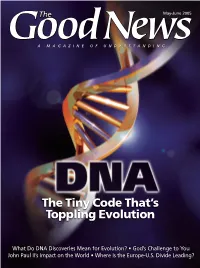

The Tiny Code That's Toppling Evolution

May-June 2005 A MAGAZINE OF UNDERSTANDING The Tiny Code That’s Toppling Evolution What Do DNA Discoveries Mean for Evolution? • God’s Challenge to You John Paul II’s Impact on the World • Where Is the Europe-U.S. Divide Leading? GN#58 Section 1.6.indd 1 4/21/05 9:15:23 AM Intelligent Design n our last issue, we reported in our new feature “God, Science and the Bible” on British phi- May/June 2005 Volume 10, Number 3 Circulation: 428,000 The Good News (ISSN: 1086-9514) is published bimonthly by the United Church of God, an Ilosophy professor Antony Flew, considered the International Asso cia tion, 555 Technecenter Dr., Milford, OH 45150. © 2005 United Church of God, world’s best-known atheist, bowing to mounting scientifi c evidence an International Asso ciation. Printed in U.S.A. All rights reserved. Repro duction in any form without written permission is prohibited. Periodi cals Postage paid at Milford, Ohio 45150, and at additional proving the existence of God. mailing offi ces. Scriptural references are from the New King James Version (© 1988 Thomas Nelson, Flew said his current ideas are similar to those of American “intel- Inc., publishers) unless otherwise noted. ligent design” (ID) theorists, who see evidence for an intelligent Dona tions to help share The Good News and our other free publications with others are grate fully guiding force in the universe’s construction. accepted and are tax-deductible in the United States and Canada. Those who choose to voluntarily support this work are welcomed as coworkers in this effort to proclaim the true gospel to all nations. -

Otero-Autobiography

Otero\Enemy 607 CHAPTER 14 POVERTY IS THE GREATEST VIOLENCE Mahatma Gandhi The Riot in the Miami Ghettos. The killing of Arthur McDuffy in Miami by local cops created tension in the ghettos of the Black community. To pacify the Black community, the State Attorney's office filed criminal charges against the police officers for the assassination of McDuffy. Circuit County Judge Leonord Nesbitt presided over the trial, and Hank Adorno and George Yoss were the acting prosecutors, hungry for publicity. They were a team of judicial clowns. The trial was granted a change of venue to Tampa, where Judge Nesbitt provided devious instructions to the state jury to acquit the police officers of the violation of excessive use of force. The acquittal caused another riot in Liberty City. Under heavy political pressure from the now well-organized Black communities in the United States and feeling embarrassed by the incident, the Federal Government filed charges against all the police officers for violation of civil rights. During the preliminary proceedings the court received telephone calls, made apparently by police officers, issuing a warning that a bomb would detonate inside the courthouse. Of course, the legal proceedings were canceled because of the potential violence that the local trial might generate in the Black community as well as the police officers who were discontented with the criminal charges against their co-workers. Eventually, the circuit judge granted the petition filed by the defense for a change of venue to Atlanta, Georgia. Subsequently, the case continued to seek jurisdiction in Texas, where the police officers were acquitted. -

Top 100 of 2020

THE MUSIC NEVER STOPS theYEAR If it's 10,000 hours or the rest of my life, I'm gonna love you in MUSIC Ridin' roads that don't nobody go down When the bones are good, the rest don't matter TOP 100 If home is where the heart is, I'm homesick for you Everything I love is homemade OF 2020 Even if it's just a slow dance in a parking lot Chasin' You Big Loud CARRIE UNDERWOOD Drinking Alone Capitol 1 MORGAN WALLEN 51 2 MAREN MORRIS The Bones Columbia 52 RILEY GREEN I Wish Grandpas ... BMLGR 3 GABBY BARRETT I Hope Warner/WAR 53 JON PARDI Ain't Always The Cowboy Capitol You got me tryna catch my breath Big, Big Plans Big Loud 4 SAM HUNT Kinfolks MCA 54 CHRIS LANE 5 LUKE COMBS Even Though I'm ... River House/Columbia 55 ERIC CHURCH Monsters EMI Nashville I don't wanna love nobody but you 6 TRAVIS DENNING After A Few Mercury 56 GARTH BROOKS & BLAKE SHELTON Dive Bar Pearl 7 BLAKE SHELTON f/GWEN STEFANI Nobody But You Warner/WMN 57 MORGAN WALLEN More Than My ... Big Loud 8 OLD DOMINION One Man Band RCA 58 BLAKE SHELTON f/GWEN STEFANI Happy Anywhere Warner/WMN After a few drinks, it's always the same thing 9 DUSTIN LYNCH Ridin' Roads Broken Bow 59 KELSEA BALLERINI Homecoming Queen? Black River 10 JAKE OWEN Homemade Big Loud 60 LADY A Champagne Night BMLGR 11 LUKE COMBS f/ERIC CHURCH Does To Me River House/Columbia 61 MICHAEL RAY Her World Or Mine Warner/WEA I'm somewhere in between Momma's House Broken Bow 12 MADDIE & TAE Die From A Broken Heart Mercury 62 DUSTIN LYNCH I hope you're happy now 13 CARLY PEARCE & LEE BRICE I Hope You're Happy Now Big Machine/Curb 63 GONE WEST What Could've Been Triple Tigers 14 BRETT YOUNG Catch BMLGR 64 KENNY CHESNEY Happy Does Blue Chair/Warner/WEA 15 THOMAS RHETT f/JON PARDI Beer Can't Fix Valory/Capitol 65 MIDLAND Cheatin' Songs Big Machine You're playin' hard to forget 16 DAN + SHAY & JUSTIN BIEBER 10,000 Hours Warner/WAR 66 DAN + SHAY I Should Probably Go .. -

Indianism and the Modernist Literary Field

ABORIGINAL ISSUES: INDIANISM AND THE MODERNIST LITERARY FIELD By Elizabeth S. Barnett Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2013 Nashville, TN Approved: Professor Vera Kutzinski Professor Mark Wollaeger Professor Allison Schachter Professor Ellen Levy For Monte and Bea ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have been very fortunate in my teachers. Vera Kutzinski’s class was the first moment in graduate school that I felt I belonged. And she has, in the years since, only strengthened my commitment to this profession through her kindness and intellectual example. Thank you for five years of cakes, good talks, and poetry. One of my fondest hopes is that I have in some way internalized Mark Wollaeger’s editorial voice. He has shown me how to make my writing sharper and more relevant. Allison Schachter has inspired with her range and candor. My awe of Ellen Levy quickly segued into affection. I admire her way of looking, through which poetry and most everything seems more interesting than it did before. My deep thanks to Vanderbilt University and to the Department of English. I’ve received a wonderful education and the financial support to focus on it. Much of this is due to the hard work the Directors of Graduate Studies, Kathryn Schwarz and Dana Nelson, and the Department Chairs, Jay Clayton and Mark Schoenfield. I am also grateful to Professor Schoenfield for the opportunity to work with and learn from him on projects relating to Romantic print culture and to Professor Nelson for her guidance as my research interests veered into Native Studies.