The Dynamics of Network Shutdowns and Collective Action Responses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

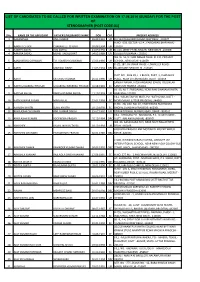

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

New Rebel Invasion Forco Heads to Cuba^ Thousands Reported Dead

•4 ' . : / •'- -T'. THURSDAY, APRIL 20, I9 «l PAGE TWENTY Averse* Osily Net Press Run The Westher ■ l3Ianri|(Bt(r lEvfntng lirralb For tho Wohk EaSod Much n . IMl Foroout of E . B. Woathor B i ^ s 13,317 Some doudbwee end* mild to A b o u t T o w n night end Satontoy. Low tonight Member of tho AaO^ BnreMi of Otronlatlon 40-45. High Saturday in Uw OOe. ■ "nie &p»er Club will hold a «et- Manchester— A City of Village Charm party Saturday night at 8 o'clock for members and friends. BeCreahments will be served dur (ClaMtfled Advertlalng on Page S2) ing Intermission. VOL. LXXX, NO. 171 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGES— IN TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, APRIL 21, 1961 PRICE FIVE CENTS >eip. Gail Eagleson, daughter of ; Mra. Robert Eagleson. 637 S. Main ; i St„ baa been elected vice, pres- |: Ident Ol the Student New Hamp- i ; ahlre Education Association. She is | i a Junior, majoring in elementar.v |; education. *t Pl>Tnouth Teachers : College, Plymouth. N. H. I KNOWS YOUR TYPE! New Rebel Invasion Forco Heads to Cuba^ The Girls’ Friendly Sponsors of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church will meet tomorrow at 8 p.m. in the visual aid room of the church. , Members are asked to bring | for whatever your figure... articles' for a Chinese auction. , Hostesses will be Miss Hannah ! Thousands Reported Dead in Earlier Fight Jensen. Mrs. Allan Hotchkiss, and , Mrs. Henrj’ Perk. I - whatever your problem... Tlia University of New Hamp- : aMre Alumni Club for Greater ; open Hartford area will be host to the State News university’s president. -

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018 March in History Nation celebrates Pakistan Day 2018 with military parade, gun salutes March 15, 1955: The biggest contingents of armoured and mech - post-independence irrigation anised infantry held a march-past. project, Kotri Barrage is Pakistan Army tanks, including the inaugurated. Al Khalid and Al Zarrar, presented March 23 , 1956: 1956 Constitution gun salutes to the president. Radar is promulgates on Pakistan Day. systems and other weapons Major General Iskander Mirza equipped with military tech - sworn in as first President of nology were also rolled out. Pakistan. The NASR missile, the Sha - heen missile, the Ghauri mis - March 23, 1956: Constituent sile system, and the Babur assembly adopts name of Islamic cruise missile were also fea - Republic of Pakistan and first constitution. The nation is celebrating Pakistan A large number of diplomats from tured in the parade. Day 2018 across the country with several countries attended the March 8, 1957: President Various aeroplanes traditional zeal and fervour. ceremony. The guest of honour at Iskandar Mirza lays the belonging to Army Avi - foundation-stone of the State Bank the ceremony was Sri Lankan Pres - Pakistan Day commemorates the ation and Pakistan Air of Pakistan building in Karachi. ident Maithripala Sirisena. passing of the Lahore Resolution Force demonstrated aer - obatic feats for the March 23, 1960: Foundation of on March 23, 1940, when the All- Contingents of Pakistan Minar-i-Pakistan is laid. India Muslim League demanded a Army, Pakistan Air Force, and audience. Combat separate nation for the Muslims of Pakistan Navy held a march-past and attack helicopters, March 14, 1972: New education the British Indian Empire. -

Examination of the Use of Online and Offline Networks by Housing Social Movement Organizations

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Sociology Sociology 2013 Examination of the Use of Online and Offline Networksy b Housing Social Movement Organizations Jessica N. Kropczynski University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kropczynski, Jessica N., "Examination of the Use of Online and Offline Networksy b Housing Social Movement Organizations" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--Sociology. 11. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/sociology_etds/11 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Sociology by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Amid Deepening Ties, Chinese Troops Join Pakistan Day Parade

International17 FRIDAY, MARCH 24, 2017 Poor patients turned away as doctors protest assaults in India MUMBAI: Poor patients in western India were unable a lobbying group, supported the strike after dozens in recent years have been triggered by frustrations to access care for a fourth day as doctors at state hos- of attacks on doctors in recent years, some resulting with the public healthcare system, analysts say. State pitals extended a strike protesting assaults by in serious injuries, said IMA vice president R.V. hospitals are generally overcrowded and under- patients’ families, adding pressure to an overbur- Asokan. “We are only asking for security in the work- staffed, with filthy, outdated facilities. dened public healthcare system. The high court in place, which every worker is entitled to. Doctors are The government in its National Health Policy Mumbai yesterday ordered doctors in Maharashtra already working under tremendous stress,” he said. released last week called for restructuring the public state to resume work immediately and asked the India is emerging as a medical tourism destination healthcare system and increasing health spending to government to ensure their security, as pregnant with modern, well-equipped hospitals offering quali- 2.5 percent of GDP by 2025, which is half of what the women and kidney dialysis patients were turned ty care at competitive rates compared to western World Health Organization recommends. In addition, away from hospitals and surgeries postponed. countries, but the country’s poor depend on poorly doctors are calling for more security personnel and Hundreds of doctors went on strike in New Delhi funded state hospitals. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

A ^Vved RUR^R E

$ % ?$ 2 #; #; ; *6#$* 78 '*'*+ &'( ) ,'(-). 27*:"=. **$-: 1-%7=3%-::".=7=7 7-.$7 7-:1- 7* 9*3 ! " # ""#$!#% %#%#% 1=%7-%A NA::=95"$O-$$-%<=32=:*% .*.-%:4&9=7: %42 #&#%%# % )+#5**1 06B C- " - 0 ' 8 9% 7: ! " % 39 :8* Addressing a joint Press Taking a dig at the BJP, # conference with Paswan and Tejashwi tweeted that despite ays after the Lok Janshakti Bihar Chief Minister Nitish having achieved power through " DParty served an ultimatum Kumar, BJP president Amit the back door in Bihar and hav- on the BJP to end the logjam Shah asserted that the NDA ing 22 sitting MPs, the party $ over seat-sharing in Bihar, the will win more than 31 seats it agreed to give an equal num- NDA big brother made a major had in 2014 and expressed ber of seats to Nitish, who had % compromise by agreeing to confidence that it will come returned with a tally of only contest five seats less than they back to power in 2019. two seats. “Now you can under- % )%'0 7-3%8* won in the 2014 Lok Sabha The deal suggests a victo- stand the dire straits the NDA polls in Bihar, allotting 17 seats ry of sorts for the LJP, which is in,” the RJD leader said. n a stunning victory to the Janata Dal(U) and six to had adopted an aggressive Ending its 17-year-old ICongress’ Naman Bixal the LJP. The BJP will contest 17 stand seeking a better bargain alliance with the NDA, the Kongadi became the new MLA of the 40 seats in the State. -

Total No. of Diesel Vehicles Registered in RAJA GARDEN Before 07-Nov-2001 Not Have Valid

Total No. of Diesel Vehicles is registered before 07-nov-2001 or 15 years old and not have valid fitness on 08-nov-2016 Sno regn_no regn_dt fit_upto owner_name f_name p_add1 p_add2 p_add3 p_pincode descr off_name 68886 DL4CM1773 27-04-2000 26-04-2015 SATISH KUMAR SHRI RAM 76/9 KISHAN GARH VILLAGE NEW DELHI 110000 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68887 DL4CM5006 11-10-2000 10-10-2015 RAMESHWAR DAYAL GUPTA A PRASAD G-2/43 & 44 MANGOL PURI NEW DELHI 110083 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68888 DL4CJ3024 06-07-1999 05-07-2014 KISHAN LAL HARISH CHANDER E-144 NAND RAM PARK MAHAVIR ENCLAVE-III NEW DELHI 110000 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68889 DL4CM4533 14-09-2000 13-09-2015 VIJAY GUPTA HARI KISHAN 454 ASOLA FATEH PUR BERI NEW DELHI 110030 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68890 DL4CM5542 15-11-2000 14-11-2015 MOHAMMAD FIROZ MOHAMMAD YASEEN 11123 STREET LEATHER WALI IDGAH ROAD PAHAR GANJ NEW DELHI 110055 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68891 DL4CM8833 07-06-2001 06-06-2016 SATYAPAL NARANG NA 188 AVTAR INCLAVE PASCHIM VIHAR NEW DELHI 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68892 DL4CM8857 08-06-2001 07-06-2016 PANKAJ SHARMA SH MADAN LAL A-383 SHASTRI NAGAR DELHI . 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68893 DL4CM8941 12-06-2001 11-06-2016 NEW AGE HOSE MFG.CO. J-6-151 RAJOURI GDN EXTN NEW DELHI 27 . 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68894 DL4CM8978 14-06-2001 12-06-2016 POOJA SHARMA NA C 6A/27-A JANAK PURI NEW DELHI 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68895 DL4CM9354 04-07-2001 03-07-2016 M/S A K INDUSTRIES NA D-71 SUDERSHAN PARK NEW DELHI-15 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68896 DL4CM9182 25-06-2001 24-06-2016 NATIONAL INSU CO LTD NA C-3, PUJA HOUSE KARAM PURA NEW DELHI 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68897 DL4CM9301 29-06-2001 28-06-2016 DINESH KUMAR RAM SINGH 11/4 BHOGAL ROAD NEW DELHI 110000 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68898 DL4CM9276 28-06-2001 27-06-2016 SHER SINGH SH FAQIR SINGH 38 D-2 SULTAN PURI DELHI 0 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68899 DL4CM8801 06-06-2001 05-06-2016 LAXMI VIRENDER 348, BAPROLA BAPROLA VILLAGE DELHI 110000 DIESEL RAJA GARDEN 68900 DL4CM8768 02-06-2001 01-06-2016 GURMEL SINGH . -

Electricalpocketguide Booklet.Pdf

P O C K E T GUIDE Electrical Energy 101 Providing technical leadership for the telecommunications industry and serving its members through professional development, standards, certification and information. Join today - www.scte.org Alpha Pocket Guide Electrical Energy 101 Copyright © 2012 Alpha Technologies Inc. All Rights Reserved. Alpha is a registered trademark of Alpha Technologies. Reproduction in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of Alpha is strictly forbidden. For more information, contact Alpha. Trademarks The capabilities, system requirements and/or compatibility with third-party products described herein are subject to change without notice. Alpha, the Alpha Logo, , CableUPS® are all trademarks of Alpha Technologies Inc. All other trade names and product names herein, including those related to third party products and services are trademarks of their respective owners. Information on trademarks used in this reference book are listed below. ANSI® is a registered trademark of the American Standards Institute. NEMA® is a registered trademark of the National Electric Manufacturers Association. The National Electric Code® is a registered trademark. NFPA 70®, NFPA 78® is a registered trademark of the National Fire Protection Association, Inc. Contents and specifications in this reference book are subject to change without notice. Alpha reserves the right to change the content as circumstances may warrant. Alpha Technologies Inc., a member of The Alpha Group, provides the communications industry with the most reliable, technologically advanced and cost-effective powering solutions available. Alpha offers innovative powering solutions that are designed for the future, built to support expansion and provide unlimited opportunity. Widely used in cable television, communications and data networks worldwide, Alpha products have earned a reputation for reliability and performance. -

Starview E-Paper

8 ECONOMY & PUBLIC AFFAIRS MUMBAI | FRIDAY, 1 JUNE 2018 1 > United opposition triumphs After defeat, BJP now the target of allies, rivals ARCHIS MOHAN chief to convince him to keep prices. over BJP in by-elections New Delhi, 31 May the BJP-Sena alliance intact for In Lucknow, Samajwadi the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Party chief Akhilesh Yadav too ARCHIS MOHAN retained two seats. In West The by-poll results of four Lok The JD(U)’s loss suggested acknowledged the support of New Delhi, 31 May Bengal, the Trinamool Congress Sabha and 10 assembly seats an erosion in Bihar Chief AAP, along with that of other increased its winning margin in across 11 states have caused Minister Nitish Kumar’s sup- opposition parties, for the he results of four Lok Maheshtala Assembly, with the murmurs of discontent in the port base and increasing accept- Kairana Lok Sabha and Sabha and 10 assembly party crediting the victory to Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)- ance of the RJD under Tejashwi Noorpur assembly wins. T by-polls, announced on Lok Sabha MP and Chief led National Democratic Yadav. The JD(U) defeat could Rashtriya Lok Dal’s Jayant Thursday reinforced the idea of Minister Mamata Banerjee's Alliance. spur desertions of Yadav and Chaudhary also thanked the a united Opposition that parties nephew, Abhishek Banerjee. The results also had leaders Muslim legislators of his party. AAP. have been working on to fight Of the four Lok Sabha by- of the Telugu Desam Party Meanwhile, Andhra Communist Party of India the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, and polls that went to polls on (TDP) and Aam Aadmi Party Pradesh Chief Minister N (Marxist) General Secretary sent Bharatiya Janata Party Monday, the BJP could only win (AAP) discover redeeming fea- Chandrababu Naidu said the Sitaram Yechury said the by- strategists back to the drawing one. -

NW-109 Wainganga-Pranahita River Final

Final Feasibility Report National Waterway-109 Region V – Wainganga-Pranahita River Kaleshwaram to Chandapur (165.78km) SURVEY PERIOD: 30 MAY 2016 TO 03 JUL 2016 Volume - I Prepared for: Inland Waterways Authority of India (Ministry of Shipping, Govt. of India) A-13, Sector – 1, NOIDA Distt. Gautam Budh Nagar, Uttar Pradesh – 201 301 Document Distribution Date Revision Distribution Hard Copy Soft Copy INLAND WATERWAYS 9 Dec 2016 Rev – 0 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 21 Apr 2017 Rev – 1.0 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 01 Dec 2017 Rev – 1.1 04 04 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 26 Oct 2018 Rev – 1.2 04 04 AUTHORITY OF INDIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENT IIC Technologies Ltd. expresses its sincere gratitude to IWAI for awarding the work of carrying out detailed hydrographic surveys in the New National Waterways in NW-109 in Region V – from Kaleshwaram to Chandapur village. We would like to use this opportunity to pen down our profound gratitude and appreciations to Shri Pravir Pandey, IA&AS, Chairman IWAI for spending his valuable time and guidance for completing this Project. IIC Technologies Ltd., would also like to thank, Shri Alok Ranjan, ICAS, Member (Finance), Shri Shashi Bhushan Shukla, Member (Traffic), Shri S.K. Gangwar, Member (Technical) for their valuable support during the execution of project. IIC Technologies Ltd, wishes to express their gratitude to Capt. Ashish Arya, Hydrographic Chief IWAI, Cdr. P.K. Srivastava ex-Hydrographic Chief and Shri SVK Reddy, Chief Engineer-I for their guidance and inspiration for this project. IIC Technologies Ltd, would also like to thank Sh. -

Global Extremism Monitor

Global Extremism Monitor Violent Islamist Extremism in 2017 WITH A FOREWORD BY TONY BLAIR SEPTEMBER 2018 1 2 Contents Foreword 7 Executive Summary 9 Key Findings About the Global Extremism Monitor The Way Forward Introduction 13 A Unifying Ideology Global Extremism Today The Long War Against Extremism A Plethora of Insurgencies Before 9/11 A Proliferation of Terrorism Since 9/11 The Scale of the Problem The Ten Deadliest Countries 23 Syria Iraq Afghanistan Somalia Nigeria Yemen Egypt Pakistan Libya Mali Civilians as Intended Targets 45 Extremist Groups and the Public Space Prominent Victims Breakdown of Public Targets Suicide Bombings 59 Use of Suicide Attacks by Group Female Suicide Bombers Executions 71 Deadliest Groups Accusations Appendices 83 Methodology Glossary About Us Notes 3 Countries Affected by Violent Islamist Extremism, 2017 4 5 6 Foreword Tony Blair One of the core objectives of the Institute is the promotion of co-existence across the boundaries of religious faith and the combating of extremism based on an abuse of faith. Part of this work is research into the phenomenon of extremism derived particularly from the abuse of Islam. This publication is the most comprehensive analysis of such extremism to date and utilises data on terrorism in a new way to show: 1. Violent extremism connected with the perversion of Islam today is global, affecting over 60 countries. 2. Now more than 120 different groups worldwide are actively engaged in this violence. 3. These groups are united by an ideology that shares certain traits and beliefs. 4. The ideology and the violence associated with it have been growing over a period of decades stretching back to the 1980s or further, closely correlated with the development of the Muslim Brotherhood into a global movement, the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and—in the same year—the storming by extremist insurgents of Islam’s holy city of Mecca.