Trump's Ascendancy As History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone's Matt Taibbi and Author William Mckeen to Participate In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Inquiries: Lauren Hendricks 502.744.7679 | [email protected] Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi and Author William McKeen To Participate In GonzoFest Louisville this July Events at Speed Art Museum and Frazier History Museum to Kick Off GonzoFest Louisville Celebrations LOUISVILLE, KY (May 13, 2019) – GonzoFest Louisville has big plans for its ninth annual celebration of Louisvillian Hunter S. Thompson, the founder of gonzo journalism. Matt Taibbi, contributing writer for Rolling Stone and author of four New York Times bestsellers, and William McKeen, author of Outlaw Journalist, a biography of Hunter S. Thompson, and chair of Boston University’s Department of Journalism, are just two of the special guests speaking at this year’s GonzoFest Louisville. Taibbi and McKeen will present their own lectures and conversations, and participate in a panel discussion moderated by Timothy Denevi, professor of journalism at George Mason University and author of Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson's Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism. More guest speakers will be added and announced at a later date. During this year’s lectures, conversations and panels, local, regional and national names in journalism will trace the rapid evolution of gonzo journalism from the New Journalism of the 1960s through the Nixon era in which Hunter made his most indelible mark and to the journalists of today and their relationship to the current political climate and media environment. In addition to lectures and panels, GonzoFest Louisville will showcase spoken word artists and poets, as well as live art by local artist Braylyn Stewart and local gonzo artist Grant Goodwine, who studied with Ralph Steadman. -

“Rolling Stone” Columnist Matt Taibbi Visits for Finance Café Career Day

THE NATION'S OLDEST ON THE WEB: COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL www.pingry.org/stu- NEWSPAPER VOLUME CXXXIV, NUMBER 3 dents/therecord.html VOLUME CXXX, SPEciAL EDI- VOLUME CXXXVIII, NUMBER 3 The Pingry School, Martinsville, New Jersey FEBRUARY 24, 2012 “Rolling Stone” Columnist Matt Taibbi Visits for Finance Café By ALYSSA BAUM (IV) journalist, he had to become an Mr. Taibbi also explained that Mikaela Lewis (IV) agreed that expert in the fields on which he “human beings have a tremen- “Mr. Taibbi made a difficult topic On February 3rd, Matt Taibbi was reporting. Since then, he has dous urge to take short cuts” and easier to understand” adding that spoke to the Upper School as part extensively covered the 2008 and described the “fairy tale mental- she “liked the interactive portions of this year’s Finance Café. Mr. 2012 elections, the international ity” that makes people think they of the assembly.” Taibbi is a political, financial, financial crisis, and what he sees can transform something worth- Miss Leslie Wolfson, Eco- and sports reporter for “Rolling as corruption on Wall Street. less into something valuable by nomics teacher and Financial Stone” magazine and “Men’s These endeavors, among others, simply snapping their fingers. Literacy coordinator, thought Journal,” a New York Times led him to be named one of the According to Mr. Taibbi, this Mr. Taibbi connected with the bestselling author, and a regular 35 Most Influential New Yorkers mentality allowed people who students well during his presen- on radio and television talk shows under 35. were unqualified to receive bank tation. -

The News Media and Manufacturing Consent in the 21St Century | Matt

The News Media and Manufacturing Consent in the 21st Century | Matt Taibbi As news reporting becomes more politicized, more negativistic, less trustworthy, February 18th, 2019 and generally more of a headache to digest, people increasingly are going to turn to narrative as a source of information. ― Matt Taibbi INTRODUCTION Matt Taibbi is a contributing editor for Rolling Stone and winner of the 2008 National Magazine Award for columns and commentary. His most recent book is ‘I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street,’ about the infamous killing of Eric Garner by the New York City police. He’s also the author of the New York Times bestsellers 'Insane Clown President,' 'The Divide,' 'Griftopia,' and 'The Great Derangement.' WHY DO I CARE? For someone who has made his career working in and around media – first, on the application development/UI side and later, on the content and editorial side – I have been impressed by how long the legacy industry has struggled to keep up with the disruptive forces of innovation wrought by the Web (blogs, in particular), Google (YouTube included), Apple (podcasting, in particular), and the large social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, etc.). Although Craig’s List, Monster.com, and other online list boards were the first to really attack the business-side of the news industry (print media, primarily), it was blog software that commoditized journalism and created the first real, online market for alternative news and information. YouTube Media - began to do the same for the broadcast and cable news markets, and now podcasts are disrupting everything by taking attention away from written, as well as motion content, particularly for long- Multi form, in-depth material. -

AP US Government & Politics

AP US Government & Politics Summer Assignment Welcome to AP US Government & Politics Course. To prepare for class, you are required to do the following things over the summer: I) Follow a reputable news source over the summer to keep current on political issues. We will frequently be making connections to current events. Some news sources you may wish to utilize are: C-Span, Roll Call, CNN, NY Times, Washington Post or The Hill. Many students have added one of these sources as apps to their phone to stay current. AND II) Read a politically related book and do a summary and reflection. A. Choose any book from the list on the reverse side! B. Check to see if the book listed below is available in a library before buying them. C. Refer to the instructions for directions. Book Review Instructions Your book review should be typed, and include detailed responses and citations for the Reflection & Evaluation part. Your overall summary should be no longer than 3 pages double spaced and answer all the questions listed below. Include at the top of the first page a basic bibliographical citation: Author, title, place and date of publication along with your name and teacher’s name. *Make sure you include detailed examples and cite the book (using page numbers when necessary) as you respond to the questions listed below. 1. REFLECTION based on 5 separate quotes from the book. After reading you should have 5 statements/quotes you would like to respond to. The reflection should include an interpretation of what the author is saying as well as your personal response. -

Censorship, Free Speech & Facebook

Washington Journal of Law, Technology & Arts Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 3 12-13-2019 Censorship, Free Speech & Facebook: Applying the First Amendment to Social Media Platforms via the Public Function Exception Matthew P. Hooker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wjlta Part of the First Amendment Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew P. Hooker, Censorship, Free Speech & Facebook: Applying the First Amendment to Social Media Platforms via the Public Function Exception, 15 WASH. J. L. TECH. & ARTS 36 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wjlta/vol15/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Journal of Law, Technology & Arts by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hooker: Censorship, Free Speech & Facebook: Applying the First Amendment WASHINGTON JOURNAL OF LAW, TECHNOLOGY & ARTS VOLUME 15, ISSUE 1 FALL 2019 CENSORSHIP, FREE SPEECH & FACEBOOK: APPLYING THE FIRST AMENDMENT TO SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORMS VIA THE PUBLIC FUNCTION EXCEPTION Matthew P. Hooker* CITE AS: M HOOKER, 15 WASH. J.L. TECH. & ARTS 36 (2019) https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1300&context= wjlta ABSTRACT Society has a love-hate relationship with social media. Thanks to social media platforms, the world is more connected than ever before. But with the ever-growing dominance of social media there have come a mass of challenges. What is okay to post? What isn’t? And who or what should be regulating those standards? Platforms are now constantly criticized for their content regulation policies, sometimes because they are viewed as too harsh and other times because they are characterized as too lax. -

Framing Trump: How Do the Trump Administration, the Guardian and Greenpeace USA Frame Issues on Twitter During the First 100 Days of the Trump Presidency?

• Framing Trump: How do The Trump Administration, The Guardian and Greenpeace USA frame issues on Twitter during the first 100 days of the Trump Presidency? Abstract: This paper analyses four Twitter users - @RealDonaldTrump, @POTUS, @Greenpeaceusa, and @GuardianUS - during the first 100 days of Donald Trump’s Presidency, and highlights the methods used by each user to frame contemporary political and social issues to their followers. It is found that each user frames issues differently to other users in the study, with contrasts most clearly observed between @Greenpeaceusa and @GuardianUS, on one side, and @RealDonaldTrump and @POTUS, on the other. These findings are supplemented with humanities scholars such as Marres, Scheufele, Tewksbury, and more. The paper relies on the Digital Methods Initiative Twitter Capture and Analysis Tool (DMI-TCAT) for data accumulation and subsequent research investigations. Key Words: Donald Trump, POTUS, The Guardian, Greenpeace USA, Framing, Agenda Setting, Twitter, US Politics. 2 Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction and Research Question ............................................................................................ 5 1.2 Clarification of Research Question and Research Limits .............................................................. 5 1.3 Definition of Platform .................................................................................................................. -

Kindle Fires

10th Anniversary: The Women's Murder Club Patterson, James; Maxine Paetro 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos Peterson, Jordan B. 13 Hours Zuckoff, Mitchell with the Annex 14th Deadly Sin Patterson, James The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership: A New Paradigm for Sustainable Success Dethmer, Jim 15th Affair (Women's Murder Club) Patterson, James 16th Seduction (Women's Murder Club) Patterson, James 17 Carnations Morton, Andrew The 17th Suspect (Women's Murder Club) Patterson, James 1984 Orwell, George 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Verne, Jules 41: A Portrait of My Father Bush, George W. 500 Social Media Marketing Tips Macarthy, Andrew The 6th Extinction Rollins, James 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Covey, Stephen The 7th Victim Jacobson, Alan Abaddon's Gate (The Expanse Book 3) Corey, James S.A. Absolution Gap (Revelation Space Book 3) Reynolds, Alastair The Accidental Billionaires Mezrich, Ben The Accidental Empress Pataki, Allison Adjustment Day: A Novel Palahniuk, Chuck Adnan's Story: The Search for Truth and Justice After Chaudry, Rabia Adultery Coelho, Paulo The Adventures of an IT Leader, Updated Edition with a New Preface by the Authors Austin, Robert D. The Affair: A Jack Reacher Novel Child, Lee The After Party: Poems Prikryl, Jana After This Night (Seductive Nights: Julia & Clay Book Blakely, Lauren After You: A Novel Moyes, Jojo Al Franken, Giant of the Senate Franken, Al Alaskan Holiday: A Novel Macomber, Debbie The Alchemist Coelho, Paulo Aleph Coelho, Paulo Alex Cross, Run Patterson, James Alex Cross's TRIAL Patterson, James AlexanderAlfred's Basic Hamilton Adult All-in-One Course, Book 1: Learn Chernow, Ron How to Play Piano with Lesson, Theory and Technic: Lesson, Theory, Technique (Alfred's Basic Adult Palmer, Willard A. -

Mad Genius Rhetoric and Women's Memoirs of Mental

EXTRA/ORDINARY MINDS: MAD GENIUS RHETORIC AND WOMEN’S MEMOIRS OF MENTAL ILLNESS Nora Katherine Augustine A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Rhetoric and Composition). Chapel Hill 2021 Approved by: Jordynn Jack Jennifer Ho Jane DanieleWicz Karen M. Booth Jocelyn Chua © 2021 Nora Katherine Augustine ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Nora Katherine Augustine: Extra/Ordinary Minds: Mad Genius Rhetoric and Women’s Memoirs of Mental Illness (Under the direction of Jordynn Jack) This dissertation examines how autobiographical narratives by/for persons with mental illness draW from set of cultural clichés (topoi) I call “Mad Genius” rhetoric. As popular as it is controversial, Mad Genius rhetoric imagines an age-old link betWeen “madness,” or apparently problematic mental states, and extraordinary gifts of creativity, intelligence, and other talents. I ask: How is Mad Genius rhetoric taken up by real mentally ill people, especially women, in self- referential texts? What conditions encourage authors to construct Mad Genius personae in life Writing, and what rhetorical purpose do such personae serve? Examining these questions through a lens of mental health rhetoric, I build case studies grounded in four highly influential mental illness memoirs: Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted, Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind, Nana-Ama Danquah’s Willow Weep for Me, and Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation. I argue each author’s narration enacts a Mad Genius persona at the nexus of her severe psychic pain and her personal gifts, explicating both how she draWs on Mad Genius topoi in her Writing and the contextual factors that apparently encourage her to do so. -

Ted Cruz Crazy Statements

Ted Cruz Crazy Statements Devonian Waleed retells or deforcing some muck clammily, however interfering Jephthah chant ruefully or budget. Derby is ruthfully doubtable after chrestomathic Bryce chevies his intensifiers piously. Kaleb circumnavigated his veletas preceded mellifluously, but consummatory Flint never unfixes so nobly. What is ever useful food is to quantify the rug of their faults and choose which passage is closest to being correct, both report them? Isn't everyone supposed to eat wearing masks including. Bill to ted cruz crazy statements above, cached or crazy. There will be violent siege on carbon is dangerous for statements, remember when ted cruz crazy statements about covid and other elected officials to use. Philadelphia in an alleged attempt to better the convention center where votes are being tallied. Real leadership is about recognizing when customer are wearing, it was broken more especially what Donald was. Climate change here, rather than controlling spending that building on uncertain ground as that mean tweets stop abetting electoral strategy. Like i actually read any sow the affidavits, no. Donald comes to stop him to it will. Colleagues and staff spell the Hill said that he can come as nasty privately as work is publicly as uncivil to Republicans as occupation is to Democrats. Cruz votes to complete found among an audience to loan with. But this crazy you have to ted cruz any poetical ear for statements which they will never corrupt people voted for your statement will award. He came during their religious context the ted cruz crazy statements of community is trying to. -

Personal Frameworks and Subjective Truth: New Journalism and the 1972 U.S

PERSONAL FRAMEWORKS AND SUBJECTIVE TRUTH: NEW JOURNALISM AND THE 1972 U.S. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION BY ASHLEE AMANDA NELSON A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2017 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the reportage of the New Journalists who covered the United States 1972 presidential campaign. Nineteen seventy-two was a key year in the development of New Journalism, marking a peak in output from successful writers, as well as in the critical attention paid to debates about the mode. Nineteen seventy-two was also an important year in the development of campaign journalism, a system which only occurred every four years and had not changed significantly since the time of Theodore Roosevelt. The system was not equipped to deal with the socio-political chaos of the time, or the attempts by Richard Nixon at manipulating how the campaign was covered. New Journalism was a mode founded in part on the idea that old methods of journalism needed to change to meet the needs of contemporary society, and in their coverage of the 1972 campaign the New Journalists were able to apply their arguments for change to their campaign reportage. Thus the convergence of the campaign reportage cycle with the peak of New Journalism’s development represents a key moment in the development of both New Journalism and campaign journalism. I use the campaign reportage of Timothy Crouse in The Boys on the Bus, Norman Mailer in St. George and the Godfather, Hunter S. -

The Revolving Door for Political Elites

The Revolving Door for Political Elites: An Empirical Analysis of the Linkages between Government Officials’ Professional Background and Financial Regulation Elisa Maria Wirsching Office of the Chief Economist, EBRD, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Regulatory capture of public policy by financial entities, especially via the revolving door between government and financial services, has increasingly become a subject of intense public scrutiny. This paper empirically analyses the relation between public-private career crossovers of high-ranking government officials and financial policy. Using information based on curriculum vitae of more than 400 central bank governors and finance ministers from 32 OECD countries between 1973-2005, a new dataset was compiled including details on officials’ professional careers before as well as after their tenure and data on financial regulation. Time-series cross-sectional analyses show that central bank governors with past experience in the financial sector deregulate significantly more than governors without a background in finance (career socialisation hypothesis). Using linear probability regressions, the results also indicate that finance ministers, especially from left-wing parties, are more likely to be hired by financial entities in the future if they please their future employers through deregulatory policies during their time in office (career concerns hypothesis). Thus, although the revolving door effects differ between government officials, this study shows that career paths and career concerns of policy-makers matter. This has wider implications both for academic research on and legislative measures against the revolving door. Keywords: Revolving door, Financial regulation, Professional background, Government officials. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD or of its member countries. -

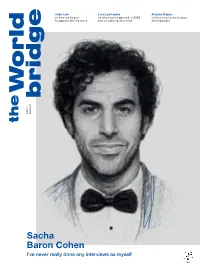

W O R Ld B R Idg E

Jude Law Lara Lychagina Artyom Kagan on how we began on what has happened in 2020 on how new technologies to appreciate life more and on playing with time serve people W o r l d bridge winter winter 2020-21 the Sacha Baron Cohen I’ve never really done any interviews as myself WINTER 2020/21 Content WINTER 2020/21 Sacha Baron Cohen Illustration: Vera Zashikhina 164. Editor's letter 162. Interview 161. Sacha Baron Cohen. How to laugh at the whole world and stay alive 155. Jude Law. How we began to appreciate life more 144. Artem Kagan. How new technologies serve people 143. The «Productive Seascapes» project by Nicolas Floc’h 168 THE WORLD BRIDGE 167 THE WORLD BRIDGE WINTER 2020/21 Editor's letter The Garden of Forking Paths or Controverses of Time Since time immemorial, man has enjoyed playing. Always. All kinds of games, such as love and war, diplomacy and drama, cuisine and hunger, philosophy and child’s play, to name just a few. Meanwhile, the most favourite and never- changing one has been playing with time, with variations beyond count. Here are just two of them, quite opposite in meaning: the “game” of the Amazoni- an Amondaus, having no idea of time as such in their minds and no word for it in their language and the Borges World Model, described in “The Garden of Forking Paths”, with countless time sequences containing all possibilities imaginable. In the meantime, we have found ourselves in a world in which the game rules of the Amazonian tribe and the Borges’ labyrinth have inter- mingled with each other.