Anton De Kom and the Formative Phase of Surinamese Decolonization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magazine

in this edition : THE 3 Joris Ivens on DVD The release in Europe 6 Joris Ivens 110 Tom Gunning MAGAZINE 9 Politics of Documen- tary Nr 14-15 | July 2009 European Foundation Joris Ivens Michael Chanan ar ers y Jo iv r 16 - Ivens, Goldberg & n is n I a v the Kinamo e h n t Michael Buckland s 0 1 1 s110 e p u ecial iss 40 - Ma vie balagan Marceline Loridan-Ivens 22 - Ivens & the Limbourg Brothers Nijmegen artists 34 - Ivens & Antonioni Jie Li 30 - Ivens & Capa Rixt Bosma July 2009 | 14-15 1 The films of MAGAZINE Joris Ivens COLOPHON Table of contents European Foundation Joris Ivens after a thorough digital restoration Europese Stichting Joris Ivens Fondation Européenne Joris Ivens Europäische Stiftung Joris Ivens 3 The release of the Ivens DVD-box set The European DVD-box set release André Stufkens Office 6 Joris Ivens 110 Visiting adress Tom Gunning Arsenaalpoort 12, 6511 PN Nijmegen Mail 9 Politics of Documentary Pb 606 NL – 6500 AP Nijmegen Michael Chanan Telephone +31 (0)24 38 88 77 4 11 Art on Ivens Fax Anthony Freestone +31 (0)24 38 88 77 6 E-mail 12 Joris Ivens 110 in Beijing [email protected] Sun Hongyung / Sun Jinyi Homepage www.ivens.nl 14 The Foundation update Consultation archives: Het Archief, Centrum voor Stads-en Streekhistorie Nijmegen / Municipal 16 Joris Ivens, Emanuel Goldberg & the Archives Nijmegen Mariënburg 27, by appointment Kinamo Movie Machine Board Michael Buckland Marceline Loridan-Ivens, president Claude Brunel, vice-president 21 Revisit Films: José Manuel Costa, member Tineke de Vaal, member - Chile: Ivens research -

Language Practices and Linguistic Ideologies in Suriname: Results from a School Survey

CHAPTER 2 Language Practices and Linguistic Ideologies in Suriname: Results from a School Survey Isabelle Léglise and Bettina Migge 1 Introduction The population of the Guiana plateau is characterised by multilingualism and the Republic of Suriname is no exception to this. Apart from the country’s official language, Dutch, and the national lingua franca, Sranantongo, more than twenty other languages belonging to several distinct language families are spoken by less than half a million people. Some of these languages such as Saamaka and Sarnámi have quite significant speaker communities while others like Mawayana currently have less than ten speakers.1 While many of the languages currently spoken in Suriname have been part of the Surinamese linguistic landscape for a long time, others came to Suriname as part of more recent patterns of mobility. Languages with a long history in Suriname are the Amerindian languages Lokono (Arawak), Kari’na, Trio, and Wayana, the cre- ole languages Saamaka, Ndyuka, Matawai, Pamaka, Kwinti, and Sranantongo, and the Asian-Surinamese languages Sarnámi, Javanese, and Hakka Chinese. In recent years, languages spoken in other countries in the region such as Brazilian Portuguese, Guyanese English, Guyanese Creole, Spanish, French, Haitian Creole (see Laëthier this volume) and from further afield such as varieties of five Chinese dialect groups (Northern Chinese, Wu, Min, Yue, and Kejia, see Tjon Sie Fat this volume) have been added to Suriname’s linguistic landscape due to their speakers’ increasing involvement in Suriname. Suriname’s linguistic diversity is little appreciated locally. Since indepen- dence in 1975, successive governments have pursued a policy of linguistic assimilation to Dutch with the result that nowadays, “[a] large proportion of the population not only speaks Dutch, but speaks it as their first and best language” (St-Hilaire 2001: 1012). -

Michiel Van Kempens Grote Albert Helman Biografie ‘Elk Verhaal Snijdt Pas Hout Als Het Op Ethos Berust’ Door Wim Rutgers

Michiel van Kempens grote Albert Helman biografie ‘Elk verhaal snijdt pas hout als het op ethos berust’ door Wim Rutgers “Ik heb het allemaal eerst in mijn hoofd, dat is het creatieve werk, en schrijf het vervolgens op, dat is koeliewerk.” (Albert Helman) Dat de verreweg productiefste Surinaamse auteur - Albert Helman (1903- 1996) - nu in een biografie is beschreven door de actiefste en meest betrokken chroniqueur van de Surinaamse literatuur - Michiel van Kempen - heeft een interessante ontmoeting opgeleverd. De titel van deze biografie ‘Rusteloos en overal’ slaat op ‘het leven van Albert Helman’, maar kan evengoed op de auteur van deze biografie Michiel van Kempen zélf slaan. Wie Albert Helman op zijn levenspad wil volgen is voortdurend op reis en dat heeft Van Kempen in Helmans voetsporen kennelijk gedaan. De veelzijdige kosmopolitet Helman brengt een biograaf zowel naar verre geografische streken als onvoorziene oorden van de menselijke geest. Helman was een zwerver over nagenoeg de hele aardbol. Hij woonde onder meer in Suriname, Nederland, in Spanje tijdens de Burgeroorlog, in Mexico, opnieuw in Nederland tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, daarna in Suriname waar hij minister van Onderwijs en Volksgezondheid werd en voorzitter van de Rekenkamer, vervolgens onder meer in Washington en op Tobago. Hij reisde, was ‘rusteloos en overal’ op plaatsen van zijn interesse of waar zijn talrijke diplomatieke en culturele functies hem riepen. Waar Helman was gebeurde er wat. Hij was niet alleen een groot organisator en initiator, maar ook leider bij de uitvoering en verwezenlijking van zijn ideeënstromen, die hij onvermoeibaar aan het papier toevertrouwde in zijn kleine maar regelmatige handschrift. -

Bittersweet: Sugar, Slavery, and Science in Dutch Suriname

BITTERSWEET: SUGAR, SLAVERY, AND SCIENCE IN DUTCH SURINAME Elizabeth Sutton Pictures of sugar production in the Dutch colony of Suriname are well suited to shed light on the role images played in the parallel rise of empirical science, industrial technology, and modern capitalism. The accumulation of goods paralleled a desire to accumulate knowledge and to catalogue, organize, and visualize the world. This included possessing knowledge in imagery, as well as human and natural resources. This essay argues that representations of sugar production in eighteenth-century paintings and prints emphasized the potential for production and the systematization of mechanized production by picturing mills and labor as capital. DOI: 10.18277/makf.2015.13 ictures of sugar production in the Dutch colony of Suriname are well suited to shed light on the role images played in the parallel rise of empirical science, industrial technology, and modern capitalism.1 Images were important to legitimating and privileging these domains in Western society. The efficiency considered neces- Psary for maximal profit necessitated close attention to the science of agriculture and the processing of raw materials, in addition to the exploitation of labor. The accumulation of goods paralleled a desire to accumulate knowledge and to catalogue, organize, and visualize the world. Scientific rationalism and positivism corresponded with mercantile imperatives to create an epistemology that privileged knowledge about the natural world in order to control its resources. Prints of sugar production from the seventeenth century provided a prototype of representation that emphasized botanical description and practical diagrams of necessary apparatuses. This focus on the means of production was continued and condensed into representations of productive capacity and mechanical efficiency in later eighteenth-century images. -

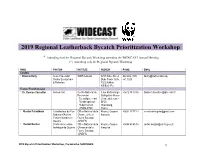

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop * Attending both the Regional Bycatch Workshop attending the WIDECAST Annual Meeting (*) Attending only the Regional Bycatch Workshop NAME POSITION INSTITUTE ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Canada: * Brianne Kelly Senior Specialist WWF-Canada 5251 Duke Street 902.482.1105 [email protected] Marine Ecosystems Duke Tower Suite ext. 3025 & Fisheries 1202 Halifax NS B3J 1P3 France/ French-Guiane * Dr. Damien Chevallier Researcher Centre National de 3 rue Michel-Ange +0612 97 10 54 [email protected] Recherche Délégation Alsace Scientifique – Inst 23 rue du Loess – Pluridisciplinaire BP20 Hubert Curien Strasbourg, (CNRS-IPHC) France * Nicolas Paranthoën Coordinateur du Plan Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 13 77 44 [email protected] National d'Actions Chasse et de la française Tortues Marines en Faune Sauvage Guyane (ONCFS) * Rachel Berzins Cheffe de la cellule Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 40 45 14 [email protected] technique de Guyane Chasse et de la française Faune Sauvage (ONCFS) 2019 Bycatch Prioritization Workshop, Paramaribo SURINAME 1 * Christelle Guyon Chargée de mission Direction de Rue Carlos +0594 29 68 60 Christelle.guyon@developpement- biodiversité marine l’Environnement, de Fineley CS 76003, durable.gouv.fr l’Aménagement et 97306 Cayenne du Logement Guyane française de Guyane * Nolwenn Cozannet Chargée du projet WWF France, 2, rue Gustave +0594 31 38 28 [email protected] Dauphin de Guyane bureau Guyane Charlery 97 300 CAYENNE -

Wikipedia Over Albert Helman

>> UITGEVERIJ SCHOKLAND • DOSSIER Albert Helman/1 Wikipedia: Albert Helman BRON: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Helman Albert Helman tegen de fascisten van Generaal Francisco Franco. Lodewijk Alphonsus Maria (Lou) Lichtveld, die later Nadat Franco in 1938 had gewonnen, vluchtte Hel- vooral onder zijn pseudoniem Albert Helman bekend man eerst naar Noord-Afrika en van daaruit naar zou worden was afkomstig uit de gekleurde elite Mexico, maar in 1939 keerde hij terug in Nederland. van Suriname en was gedeeltelijke van Indiaanse af- Hier trok hij zich het lot van de joodse vluchtelin- komst. Hij kwam als jongen van twaalf naar Neder- gen aan die vanuit Duitsland naar Nederland ko- land om aan het internaat Rolduc van het Klein Se- men. In opdracht van het Comité voor Bijzondere minarie te Roermond de priesteropleiding te gaan Joodse Belangen schreef hij het boek Millioenen-leed. volgen maar hield hier al spoedig mee op en ging teruggekeerd in Suriname een muziekopleiding Helman dook aan het begin van de oorlog onder volgen waarna hij werkzaam was als organist en omdat hij zo bekend was als antifascist dat hij niet componist. In 1922 kwam hij weer naar Nederland langer in het openbaar kon verschijnen. Actief in waar hij de kweekschool volgde en daarna musico- het verzet vervalste hij persoonsbewijzen, publi- logie studeerde. Hierna werd hij journalist en mu- ceerde verzetsverzen en protesteerde bij rijkscom- ziek recensent en sloot zich aan bij een groep jonge missaris Seyss-Inquart tegen de oprichting van de katholieken rond het tijdschrift De Gemeenschap, zogenaamde Cultuurkamer waar kunstenaars lid waar hij van 1925-1931 redacteur van was. -

Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Aminata Cairo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cairo, Aminata, "HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME" (2007). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 490. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/490 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aminata Cairo The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME ____________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aminata Cairo Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Deborah L. Crooks, Professor of Anthropology Lexington, Kentucky 2007 Copyright © Aminata Cairo 2007 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE -

Special Update on Quito Process V Technical Meeting on Human

Special update on Quito Process AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN V Technical Meeting on HumanV EMobilityNEZUVELEANNEZUE LofAN Venezuelan Citizens in the RegionREFUGEERSE F&U MGIEGERSA &N TMSIG INR ATNHTES R IENG TIOHNE REGION UNITED STATES UNITED STATES BOGOTA, COLOMBIA Havana\ MEXICO Havana\ MEXICO CUBA DOMINICAN 14-15 NOVEMBER 2019 CUBA DOMINICAN \ REPUBLIC Mexico \ HAITI \ PUERTO REPUBLIC Mexico JAMAICA \ Santo HAITI \ PUERTO City \BELIZE JAMAICA \ RICO City \ Domingo Santo RICO BELIZE Domingo \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA GUATEMALA \ \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA \ GUATEMALA \ EL SALVADOR NICARAGUA \ ARUBA CURACAO \ EL SALVADOR APoRrUt BA \NICARAGUA Spain CURACAO Port San José \ \ TRINIDAD Spain \ Panamá San JoséCaracas & TOBA\GO \ TRINIDAD PARTICIPATION COSTA \ \ Caracas Panamá & TOBAGO COSTA \ RICA PANAMA Georgetown RICA PANAMAVENEZUELA \ Georgetown VENEZ\UPaErLaAmaribo \ GUYANA Paramaribo \Bogotá \ CGayUeYnAneNA \ \Bogotá \ Cayenne COLOMBIA SURINAME COLOMBIA FRENCH SURINAME GUYANA FRENCH The fifth round of the Quito Process (Quito V – GUYANA \Quito \Quito ECUADOR Bogota Chapter) took place on 14-15 November ECUADOR (2019), with the participation of 12 States from PERU Latin America and the Caribbean, along with PERU \Lima BRAZIL key cooperating States, international financial \Lima BRAZIL \ BOLIVIA Brasilia \ BOLIVIA Brasilia institutions and other actors. \ \ Sucre Sucre PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN The meeting follows up on four previous meetings OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN QUITO V DECLARATION in September and November 2018, April and July QUITO V DECLARATION SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA 2019, as part of a government-led initiative thatArge ntina \ URUGUAY Argentina \ URUGUAY Santiago \ \ Santiago \ Brazil Buenos Montevideo \ aims to harmonize the policies and practices of Brazil Aires Buenos Montevideo Chile CHILE Aires Chile CHILE the countries in the region. -

Ethnic Diversity and Social Stratification in Suriname in 2012

ETHNIC DIVERSITY AND SOCIAL STRATIFICATION IN SURINAME IN 2012 Tamira Sno, Harry BG Ganzeboom and John Schuster No matter how we came together here, we are pledged to this ground (National Anthem Suriname) Abstract This paper examines the relative socio-economic positions of ethnic groups in Suriname. Our results are based on data from the nationally representative survey Status attainment and Social Mobility in Suriname 2011-2013 (N=3929). The respondents are divided into eight groups on the basis of self-identification: Natives, Maroons, Hindustanis, Javanese, Creoles, Chinese, Mixed and Others (mainly immigrants). We measure the socio-economic positions of the ethnic groups based on education and occupation and assess historical changes using cohort, intergenerational and lifecycle comparisons. The data allow us to create an ethnic hierarchy based on the social-economic criteria that we have used. We show that Hindustanis, Javanese and Creoles are ranked in the middle of the social stratification system of Suriname, but that Creoles have rather more favourable positions than the other two groups. Natives and Maroons are positioned at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder, and together – with almost 20% of the population - they form a sizeable lower class, also, and in increasing numbers in urban areas. At the top of the Surinamese social ladder, we find a large group of Mixed, together with the small groups of Chinese and Others. The rank order in the stratification system is historically stable. Still, there are also clear signs of convergence between the ethnic groups, in particular, when we compare the generations of respondents with their parents. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

Creole Drum. an Anthology of Creole Literature in Surinam

Creole drum An Anthology of Creole Literature in Surinam Jan Voorhoeve en Ursy M. Lichtveld bron Jan Voorhoeve en Ursy M. Lichtveld, Creole drum. An Anthology of Creole Literature in Surinam. Yale University Press, Londen 1975 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/voor007creo01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Jan Voorhoeve & erven Ursy M. Lichtveld vii Preface Surinam Creole (called Negro-English, Taki-Taki, and Nengre or more recently also Sranan and Sranan tongo) has had a remarkable history. It is a young language, which did not exist before 1651. It served as a contact language between slaves and masters and also between slaves from different African backgrounds and became within a short time the mother tongue of the Surinam slaves. After emancipation in 1863 it remained the mother tongue of lower-class Creoles (people of slave ancestry), but it served also as a contact language or lingua franca between Creoles and Asian immigrants. It gradually became a despised language, an obvious mark of low social status and lack of proper schooling. After 1946, on the eve of independence, it became more respected (and respectable) within a very short time, owing to the great achievements of Creole poets: Cinderella kissed by the prince. In this anthology we wish to give a picture of the rise and glory of the former slave language. The introduction sketches the history of Surinam Creole in its broad outlines, starting from the first published text in 1718. The texts are presented in nine chronologically ordered chapters starting from the oral literature, which is strongly reminiscent of the times of slavery, and ending with modern poetry and prose. -

Eric P. Rudge Ll.M

ERIC P. RUDGE LL.M. & LL.M. Kromanti Kodjostraat hoek Aboenawrokostraat nr. 19A, Geyersvlijt Paramaribo – Suriname S.A. Tel + app: (00597) 8835621 (mobile) Private: 00597) 455363 App nr.: (005999) 6635527 E-mail: [email protected] -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Name: RUDGE First and middle name: ERIC PATRICK Date of birth: NOVEMBER 16, 1960 Place of birth: PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Religion: ROMAN CATHOLIC Domicile: SURINAME Address: KROMANTI KODJO HK ABOENAWOKOSTRAAT nr. 19A Nationality: SURINAMESE Children: 4 (FOUR) Marital status: SEPARATED 1 EDUCATION: # Legal 2018 – April 2019 Specialized courses tailored for the members of the Judiciary in Suriname initiated by the High Court of Justice in Suriname, offered through de ‘Stichting Juridische Samenwerking Suriname Nederland’ in cooperation with ‘Studiecentrum Rechtspleging’ (SSR), Zutphen, The Netherlands July 2010 External Action and Representation of the European Union: Implementing the Lisbon Treaty, CLEER (Centre for the Law of EU External Relations) and T.M.C. Asser Institute Inter-University Research Centre, Brussels, Belgium March 2008 The Movement of Persons and Goods in the Caribbean Area, 35th External Programme, The Hague Academy of International Law in cooperation with the Government of the Dominican Republic, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic September 2007 30th Sanremo Roundtable on Current Issues of International Humanitarian Law, International Institute of Humanitarian Law (IIHL), International