Plasma Gelsolin Inhibits CD8+ T Cell Function and Regulates Glutathione

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Situlocalization of Cytoskeletal Elements in the Human Trabecular

Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. Vol. 31. No. 9. September 1990 Cops right £• Association lor Research in Vision and Ophthalmology In Situ Localization of Cytoskeletal Elements in the Human Trabecular Meshwork and Cornea Robert N. Weinreb* and Mark I. Ryderf The authors compared cytoskeletal elements of the in situ human trabccular-mcshwork cell with in situ human corneal cells using indirect immunofluorcsccncc staining for tubulin and intermediate filaments (vimentin, cytokeratin, and desmin) and NBD-phallacidin staining for f-actin using both fixed frozen and unfixed frozen sections from postmortem eyes. Both f-actin and tubulin were found throughout the cell body of trabecular-meshwork cells, keratocytes, corneal endothelium, and corneal epithelium. The f-actin staining pattern was concentrated at the cell periphery of these four cell types. Vimentin stain was intensely localized in focal areas of the trabecular-meshwork cell, keratocytes, and throughout the corneal cndothelium. A general anticytokeratin antibody was intensely localized in corneal epithelium and endothelium. However, PKK-1 anticytokeratin antibody was seen only in superficial layers of corneal epithelium and not in corneal endothelium. The 4.62 anticytokeratin antibody was not observed in either corneal epithelium or endothelium. None of these three cytokera- tin antibodies were seen in trabccular-mcshwork cells or keratocytes. Desmin stain was not noted in any of these cell types. In general, cytoskeletal staining of unfixed frozen sections showed a similar staining pattern for f-actin and tubulin but a more uniform and intense staining pattern for vimentin and cytokcratin compared with fixed frozen material. The authors conclude that these cytoskclctal stains can differentiate human Irabeciilar-meshwork cells from cells of the cornea in situ. -

Decreased Expression of Profilin 2 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Its Clinicopathological Implications

ONCOLOGY REPORTS 26: 813-823, 2011 Decreased expression of profilin 2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its clinicopathological implications C.Y. MA1,2, C.P. ZHANG1,2, L.P. ZHONG1,2, H.Y. PAN1,2, W.T. CHEN1,2, L.Z. WANG3, O.W. ANDREW4, T. JI1 and W. HAN1,2 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Ninth People's Hospital, College of Stomatology; 2Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology and Shanghai Research Institute of Stomatology; 3Department of Oral Pathology, Ninth People's Hospital, College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200011, P.R. China; 4Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore 119074, Singapore Received February 8, 2011; Accepted April 11, 2011 DOI: 10.3892/or.2011.1365 Abstract. Profilins are small proteins essential for many clinical and pathological significance. In conclusion, PFN2 normal cellular dynamics and constitute one of the crucial can be utilized as both a potential suppressor marker and a components of actin-based cellular motility. Several recent prognostic protein for OSCC. The function of PFN2 may be to studies have implicated a role for the profilin (PFN) family in regulate the N-WASP/Arp2/3 signaling pathway. cancer pathogenesis and progression. However, their expression and promising functions are largely unknown in oral squamous Introduction cell carcinoma (OSCC). In this study, we analyzed the correlation between PFN1 and PFN2 expression in vitro and Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a significant public in vivo. The protein expression levels were roughly compared health problem with >300,000 new cases being diagnosed between cell lines (HIOEC, HB96) with the employment of annually worldwide (1). -

October 2020

PCORI Health Care Horizon Scanning System: Horizon Scanning COVID-19 Supplement Status Report Volume 1, Issue 2 Prepared for: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute 1828 L St., NW, Suite 900 Washington, DC 20036 Contract No. MSA-HORIZSCAN-ECRI-ENG-2018.7.12 Prepared by: ECRI 5200 Butler Pike Plymouth Meeting, PA 19462 Investigators: Randy Hulshizer, MA, MS Marcus Lynch, PhD, MBA Jennifer De Lurio, MS Brian Wilkinson, MA Damian Carlson, MS Christian Cuevas, PhD Andrea Druga, MSPAS, PA-C Misha Mehta, MS Prital Patel, MPH Donna Beales, MLIS Eloise DeHaan, BS Eileen Erinoff, MSLIS Cassia Hulshizer, AS Madison Kimball, MS Maria Middleton, MPH Diane Robertson, BA Kelley Tipton, MPH Rosemary Walker, MLIS Karen Schoelles, MD, SM October 2020 Statement of Funding and Purpose This report incorporates data collected during implementation of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Health Care Horizon Scanning System COVID-19 Supplement, operated by ECRI under contract to PCORI, Washington, DC (Contract No. MSA- HORIZSCAN-ECRI-ENG-2018.7.12). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its content. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of PCORI. An innovation that potentially meets inclusion criteria might not appear in this report simply because the horizon scanning system has not yet detected it or it does not yet meet inclusion criteria outlined in the PCORI Health Care Horizon Scanning System: Horizon Scanning Protocol and Operations Manual COVID-19 Supplement. Inclusion or absence of innovations in the horizon scanning reports will change over time as new information is collected; therefore, inclusion or absence should not be construed as either an endorsement or rejection of specific interventions. -

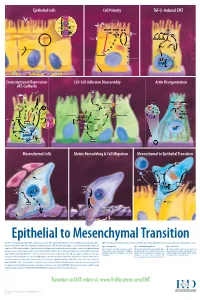

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition

Epithelial Cells Cell Polarity TGF-b-Induced EMT MUC-1 O-glycosylation Epithelial Cells ZO-1 Occludin Apical Membrane Tight F-Actin Microvilli Junction Claudin F-Actin p120 β-Catenin Adherens F-Actin Ezrin TGF-β dimer Junction E-Cadherin α-Catenin Plakophilin Crumbs Complex PAR Complex Desmocollin Desmoplakin Desmosome PtdIns(4,5)P2 TGF-β RII TGF-β RI CRB Cdc42Par6 Desmoglein Cytokeratin Pals1 PatJ Tight Junction Plakoglobin aPKC Par3 Domain Smad7 Extracellular PTEN JNK ERK1/2 p38 SARA Smurf1 Cortical Actin Cytoskeleton Space Par3 ZO-1 Adherens Junction PI 3-K Domain Smad-independent Signaling (–) Smad7 Translocation Smad2/3 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 Smad4 Smad4 NEDD4 Cytokeratin Intermediate Filaments Smad2 Smad4 Smad3 LLGL Proteasome SCRIB DLG Scribble Complex Fibronectin Twist Smad2/3 Vitronectin ZEB 1/2 Microtubule Network Smad4 N-Cadherin Snail Basolateral Membrane CoA, Collagen I Slug CoR MMPs DNA-binding (+) Claudin Desmoplakin Transcription Factor Occludin Cytokeratins E-Cadherin Plakoglobin Integrins β α Nidogen-1/Entactin Perlecan Laminin Collagen IV Transcriptional Repression Cell-Cell Adhesion Disassembly Actin Reorganization of E-Cadherin TGF-β dimer EGF TGF-β RII TGF-β RI IGF FGF Receptor TNF-α Tyrosine Kinase Par6 TNF RI Apical Focal Adhesion Constriction Actin Depolymerization F-Actin Smurf1 Occludin Wnt Frizzled Myosin II Ras RhoA α-Actinin Myosin II ROCK AxinCK1 Dishevelled GSK-3 PI 3-K Src Zyxin MLC Phosphatase APC Proteasome FAK Vinculin RhoA ILK Talin (Inactive) Hakai Talin FAK F-Actin E-Cadherin LIMK Akt Paxillin FAK Stress -

Yuri Gagarin Is Required for Actin, Tubulin and Basal Body Functions in Drosophila Spermatogenesis

1926 Research Article yuri gagarin is required for actin, tubulin and basal body functions in Drosophila spermatogenesis Michael J. Texada, Rebecca A. Simonette, Cassidy B. Johnson, William J. Deery and Kathleen M. Beckingham* Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, MS-140, Rice University, 6100 South Main Street, Houston, TX 77005, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 20 March 2008 Journal of Cell Science 121, 1926-1936 Published by The Company of Biologists 2008 doi:10.1242/jcs.026559 Summary Males of the genus Drosophila produce sperm of remarkable the yuri mutant, late clusters of syncytial nuclei are deformed length. Investigation of giant sperm production in Drosophila and disorganized. The basal bodies are also mispositioned on melanogaster has demonstrated that specialized actin and the nuclei, and the association of a specialized structure, the microtubule structures play key roles. The gene yuri gagarin centriolar adjunct (CA), with the basal body is lost. Some of (yuri) encodes a novel protein previously identified through its these nuclear defects might underlie a further unexpected role in gravitaxis. A male-sterile mutation of yuri has revealed abnormality: sperm nuclei occasionally locate to the wrong ends roles for Yuri in the functions of the actin and tubulin structures of the spermatid cysts. The structure of the axonemes that grow of spermatogenesis. Yuri is a component of the motile actin cones out from the basal bodies is affected in the yuri mutant, that individualize the spermatids and is essential for their suggesting a possible role for the CA in axoneme formation. formation. Furthermore, Yuri is required for actin accumulation in the dense complex, a microtubule-rich structure on the sperm Key words: Drosophila, Spermatogenesis, Actin, Tubulin, Basal nuclei thought to strengthen the nuclei during elongation. -

Cytoskeleton Cytoskeleton

CYTOSKELETON CYTOSKELETON The cytoskeleton is composed of three principal types of protein filaments: actin filaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules, which are held together and linked to subcellular organelles and the plasma membrane by a variety of accessory proteins Muscle Contraction • Skeletal muscles are bundles of muscle fibers • Most of the cytoplasm consists of myofibrils, which are cylindrical bundles of two types of filaments: thick filaments of myosin (about 15 run in diameter) and thin filaments of actin (about 7 nm in diameter). • Each myofibril is organized as a chain of contractile units called sarcomeres, which are responsible for the striated appearance of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Structure of muscle cells Sarcomere • The ends of each sarcomere are defined by the Z disc. • Within each sarcomere, dark bands (called A bands because they are anisotropic when viewed with polarized light) alternate with light bands (called I bands for isotropic). • The I bands contain only thin (actin) filaments, whereas the A bands contain thick (myosin) filaments. • The myosin and actin filaments overlap in peripheral regions of the A band, whereas a middle region (called the H zone) contains only myosin. Muscle contraction • The basis for understanding muscle contraction is the sliding filament model, first proposed in 1954 both by Andrew Huxley and Ralph Niedergerke and by Hugh Huxley and Jean Hanson • During muscle contraction each sarcomere shortens, bringing the Z discs closer together. • There is no change in the width of the A band, but both the I bands and the H zone almost completely disappear. • These changes are explained by the actin and myosin filaments sliding past one another so that the actin filaments move into the A band and H zone. -

Myosin-Driven Actin-Microtubule Networks Exhibit Self-Organized Contractile Dynamics Gloria Lee1, Michael J

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.11.146662; this version posted June 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Myosin-driven actin-microtubule networks exhibit self-organized contractile dynamics Gloria Lee1, Michael J. Rust2, Moumita Das3, Ryan J. McGorty1, Jennifer L. Ross4, Rae M. Robertson-Anderson1* 1Department of Physics and Biophysics, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA 92110, USA 2Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 3School of Physics and Astronomy, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY 14623, USA 4Department of Physics, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244, USA Abstract The cytoskeleton is a dynamic network of proteins, including actin, microtubules, and myosin, that enables essential cellular processes such as motility, division, mechanosensing, and growth. While actomyosin networks are extensively studied, how interactions between actin and microtubules, ubiquitous in the cytoskeleton, influence actomyosin activity remains an open question. Here, we create a network of co-entangled actin and microtubules driven by myosin II. We combine dynamic differential microscopy, particle image velocimetry and particle-tracking to show that both actin and microtubules in the network undergo ballistic contraction with surprisingly indistinguishable characteristics. This controlled contractility is distinct from the faster turbulent motion and rupturing that active actin networks exhibit. Our results suggest that microtubules can enable self-organized myosin-driven contraction by providing flexural rigidity and enhanced connectivity to actin networks. -

Ciliary Dyneins and Dynein Related Ciliopathies

cells Review Ciliary Dyneins and Dynein Related Ciliopathies Dinu Antony 1,2,3, Han G. Brunner 2,3 and Miriam Schmidts 1,2,3,* 1 Center for Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University Hospital Freiburg, Freiburg University Faculty of Medicine, Mathildenstrasse 1, 79106 Freiburg, Germany; [email protected] 2 Genome Research Division, Human Genetics Department, Radboud University Medical Center, Geert Grooteplein Zuid 10, 6525 KL Nijmegen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences (RIMLS), Geert Grooteplein Zuid 10, 6525 KL Nijmegen, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-761-44391; Fax: +49-761-44710 Abstract: Although ubiquitously present, the relevance of cilia for vertebrate development and health has long been underrated. However, the aberration or dysfunction of ciliary structures or components results in a large heterogeneous group of disorders in mammals, termed ciliopathies. The majority of human ciliopathy cases are caused by malfunction of the ciliary dynein motor activity, powering retrograde intraflagellar transport (enabled by the cytoplasmic dynein-2 complex) or axonemal movement (axonemal dynein complexes). Despite a partially shared evolutionary developmental path and shared ciliary localization, the cytoplasmic dynein-2 and axonemal dynein functions are markedly different: while cytoplasmic dynein-2 complex dysfunction results in an ultra-rare syndromal skeleto-renal phenotype with a high lethality, axonemal dynein dysfunction is associated with a motile cilia dysfunction disorder, primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) or Kartagener syndrome, causing recurrent airway infection, degenerative lung disease, laterality defects, and infertility. In this review, we provide an overview of ciliary dynein complex compositions, their functions, clinical disease hallmarks of ciliary dynein disorders, presumed underlying pathomechanisms, and novel Citation: Antony, D.; Brunner, H.G.; developments in the field. -

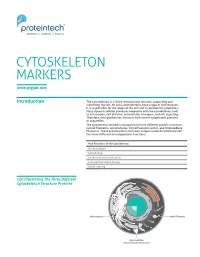

Cytoskeleton Markers

ptglab.com 1 CYTOSKELETON MARKERS www.ptglab.com Introduction The cytoskeleton is a three-dimensional network supporting and stabilizing the cell. All cells, even bacteria, have a type of cytoskeleton. It is responsible for the shape of the cell and its mechanical properties. Many dynamic cellular processes cooperate with the cytoskeleton, such as cell motion, cell division, intracellular transport, and cell signaling. Therefore, the cytoskeleton interacts with several cytoplasmic proteins or organelles. The cytoskeletal network is composed of three different protein structures named filaments: microtubules, microfilaments (actin), and intermediate filaments. These proteins form their own unique networks within the cell that have different interdependent functions. Main Functions of the Cytoskeleton Structural support Cell trafficking Transducer of mechanical signals Associated with several diseases Cellular signaling Cell Illustrating The Three Different Cytoskeleton Structure Proteins 2 Cytoskeleton Markers Most Popular Antibody Name Catalog Number Type Applications Cytoskeleton Markers ACTA2/alpha 5 23081-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, IHC, IP, WB From Proteintech smooth muscle actin alpha Tubulin 4 11224-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB beta Actin 423 20536-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, IF, IHC, WB beta Actin 399 60008-1-IG Mouse Mono ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, WB beta Tubulin 11 10068-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, IF, IHC, IP, WB Cofilin 5 10960-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, IF, IHC, WB Cytokeratin 17 specific 17516-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB Desmin 2 60226-1-IG Mouse Mono ELISA, IHC, WB GFAP 5 60190-1-IG Mouse Mono ELISA, IF, IHC, IP, WB Palladin 5 10853-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB Vimentin 54 10366-1-AP Rabbit Poly ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, WB 00 This number shows the amount of times our antibody has been cited in a publication. -

Loss of Mouse Cardiomyocyte Talin-1 and Talin-2 Leads to Β-1 Integrin

Loss of mouse cardiomyocyte talin-1 and talin-2 leads PNAS PLUS to β-1 integrin reduction, costameric instability, and dilated cardiomyopathy Ana Maria Mansoa,b,1, Hideshi Okadaa,b, Francesca M. Sakamotoa, Emily Morenoa, Susan J. Monkleyc, Ruixia Lia, David R. Critchleyc, and Robert S. Rossa,b,1 aDivision of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, CA 92093; bCardiology Section, Department of Medicine, Veterans Administration Healthcare, San Diego, CA 92161; and cDepartment of Molecular Cell Biology, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 9HN, United Kingdom Edited by Kevin P. Campbell, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, and approved May 30, 2017 (received for review January 26, 2017) Continuous contraction–relaxation cycles of the heart require ognized as key mechanotransducers, converting mechanical per- strong and stable connections of cardiac myocytes (CMs) with turbations to biochemical signals (5, 6). the extracellular matrix (ECM) to preserve sarcolemmal integrity. The complex of proteins organized by integrins has been most CM attachment to the ECM is mediated by integrin complexes commonly termed focal adhesions (FA) by studies performed in localized at the muscle adhesion sites termed costameres. The cells such as fibroblasts in a 2D environment. It is recognized that ubiquitously expressed cytoskeletal protein talin (Tln) is a compo- this structure is important for organizing and regulating the me- nent of muscle costameres that links integrins ultimately to the chanical and signaling events that occur upon cellular adhesion to sarcomere. There are two talin genes, Tln1 and Tln2. Here, we ECM (7, 8). -

Damage of Hair Follicle Stem Cells and Alteration of Keratin Expression in External Radiation-Induced Acute Alopecia

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR MEDICINE 30: 579-584, 2012 Damage of hair follicle stem cells and alteration of keratin expression in external radiation-induced acute alopecia NAOKI NANASHIMA, KOICHI ITO, TAKASHI ISHIKAWA, MANABU NAKANO and TOSHIYA NAKAMURA Department of Biomedical Sciences, Division of Medical Life Sciences, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Health Sciences, Hirosaki, Japan Received April 4, 2012; Accepted May 28, 2012 DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1018 Abstract. Alopecia is known as a symptom of acute radia- disturbances and blood and bone marrow disorders are known tion, yet little is known concerning the mechanism of this to occur within several hours to several weeks after 1-6 Gy of phenomenon and the alteration of hair protein profiles. To radiation exposure (4,6). examine this, 6-week-old male C57/BL6 mice were exposed Hair loss is also an effect of ARS, but little is known to 6 Gy of X-ray irradiation, which caused acute alopecia. about the mechanism underlying radiation-induced hair loss. Their hair and skin were collected, and hair proteins were In humans, hair loss is caused by radiation of more than analyzed with liquid chromatography/electrospray-ionization 3 Gy, and almost complete hair loss occurs within weeks of mass spectrometry and immunohistochemistry. No change exposure to 6 Gy (4,6). Since blood stem cells are sensitive to was observed in the composition of major hair keratins, such radiation (7), hair loss is thought to be caused by irradiation- as Krt81, Krt83 and Krt86. However, cytokeratin Krt15 and induced stem cell damage, yet no studies have investigated CD34, which are known as hair follicle stem cell markers, this hypothesis. -

Cytoskeletal Remodeling in Cancer

biology Review Cytoskeletal Remodeling in Cancer Jaya Aseervatham Department of Ophthalmology, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77054, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +146-9767-0166 Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 4 November 2020; Published: 7 November 2020 Simple Summary: Cell migration is an essential process from embryogenesis to cell death. This is tightly regulated by numerous proteins that help in proper functioning of the cell. In diseases like cancer, this process is deregulated and helps in the dissemination of tumor cells from the primary site to secondary sites initiating the process of metastasis. For metastasis to be efficient, cytoskeletal components like actin, myosin, and intermediate filaments and their associated proteins should co-ordinate in an orderly fashion leading to the formation of many cellular protrusions-like lamellipodia and filopodia and invadopodia. Knowledge of this process is the key to control metastasis of cancer cells that leads to death in 90% of the patients. The focus of this review is giving an overall understanding of these process, concentrating on the changes in protein association and regulation and how the tumor cells use it to their advantage. Since the expression of cytoskeletal proteins can be directly related to the degree of malignancy, knowledge about these proteins will provide powerful tools to improve both cancer prognosis and treatment. Abstract: Successful metastasis depends on cell invasion, migration, host immune escape, extravasation, and angiogenesis. The process of cell invasion and migration relies on the dynamic changes taking place in the cytoskeletal components; actin, tubulin and intermediate filaments. This is possible due to the plasticity of the cytoskeleton and coordinated action of all the three, is crucial for the process of metastasis from the primary site.