Translation of Maithilisharan Gupt's Saket

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

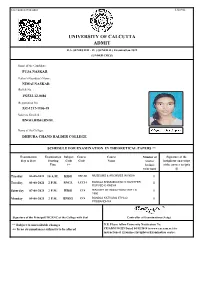

University of Calcutta Admit

532/1800865758/0401 5320942 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : PUJA NASKAR Father's/Guardian's Name : NIMAI NASKAR Roll & No. : 192532-12-0486 Registration No. 532-1212-1106-19 Subjects Enrolled : BNGG,HISG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. HISG SEC-B1 MUSEUMS & ARCHIVES IN INDIA 1 Tuesday 03-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGL LCC2-1 BANGLA BHASABIGYAN O SAHITYER 1 RUPVED O KABYA Saturday 07-08-2021 2 P.M. HISG CC4 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1 1950 Monday 09-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGG CC4 BANGLA KATHASAHITYA O 1 PROBANDHYA Signature of the Principal/TIC/OIC of the College with Seal Controller of Examinations (Actg.) ** Subject to unavoidable changes N.B. Please follow University Notification No. ++ In no circumstances subject/s to be altered CE/ADM/18/229 Dated 04/12/2018 in www.cuexam.net for instruction of Examinee/Invigilator/Examination centre. 532/1800908303/0402 5320963 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : JABA MONDAL Father's/Guardian's Name : SUBARNA MONDAL Roll & No. : 192532-12-0487 Registration No. 532-1212-1126-19 Subjects Enrolled : HISG,SOCG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana

CHAPTER – I : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Importance of Vamiki Ramayana 1.2 Valmiki Ramayana‘s Importance – In The Words Of Valmiki 1.3 Need for selecting the problem from the point of view of Educational Leadership 1.4 Leadership Lessons from Valmiki Ramayana 1.5 Morality of Leaders in Valmiki Ramayana 1.6 Rationale of the Study 1.7 Statement of the Study 1.8 Objective of the Study 1.9 Explanation of the terms 1.10 Approach and Methodology 1.11 Scheme of Chapterization 1.12 Implications of the study CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION Introduction ―The art of education would never attain clearness in itself without philosophy, there is an interaction between the two and either without the other is incomplete and unserviceable.‖ Fitche. The most sacred of all creations of God in the human life and it has two aspects- one biological and other sociological. If nutrition and reproduction maintain and transmit the biological aspect, the sociological aspect is transmitted by education. Man is primarily distinguishable from the animals because of power of reasoning. Man is endowed with intelligence, remains active, original and energetic. Man lives in accordance with his philosophy of life and his conception of the world. Human life is a priceless gift of God. But we have become sheer materialistic and we live animal life. It is said that man is a rational animal; but our intellect is fully preoccupied in pursuit of materialistic life and worldly pleasures. Our senses and objects of pleasure are also created by God, hence without discarding or condemning them, we have to develop ( Bhav Jeevan) and devotion along with them. -

Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, Bihar, India YOGA Year 7 Issue 7 July 2018

Year 7 Issue 7 July 2018 YOGA Membership postage: Rs. 100 Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, Bihar, India Hari Om YOGA is compiled, composed and pub lished by the sannyasin disciples of Swami Satyananda Saraswati for the benefit of all people who seek health, happiness and enlightenment. It contains in formation about the activities of Bihar School of Yoga, Bihar Yoga Bharati, Yoga Publications Trust and Yoga Research Fellowship. Editor: Swami Gyansiddhi Saraswati Assistant Editor: Swami GUIDELINES FOR SPIRITUAL LIFE Yogatirthananda Saraswati YOGA is a monthly magazine. Late The first wealth is health. It is the subscriptions include issues from January to December. greatest of all possessions and the basis of all virtues. One should have Published by Bihar School of Yoga, Ganga Darshan, Fort, Munger, Bihar physical as well as mental health. Even – 811201. for spiritual pursuits, good health is the Printed at Thomson Press India prerequisite. Without health, life is not Ltd., Haryana – 121007 life. The person who has good health © Bihar School of Yoga 2018 has hope, and the person who has hope has everything. Membership is held on a yearly basis. Please send your requests for The instrument must be kept clean, application and all correspondence strong and healthy. This body is a horse to: to take one to the goal. If the horse Bihar School of Yoga Ganga Darshan tumbles down, one cannot reach the Fort, Munger, 811201 destination. If this instrument breaks Bihar, India down, one will not reach the goal of - A selfaddressed, stamped envelope atmasakshatkara, selfrealization. must be sent along with enquiries to ensure a response to your request —Swami Sivananda Saraswati Total no. -

Ramakatha Rasavahini II Chapter 14

Chapter 14. Ending the Play anaki was amazed at the sight of the monkeys and others, as well as the way in which they were decorated and Jdressed up. Just then, Valmiki the sage reached the place, evidently overcome with anxiety. He described to Sita all that had happened. He loosened the bonds on Hanuman, Jambavan, and others and cried, “Boys! What have you have done? You came here after felling Rama, Lakshmana, Bharatha, and Satrughna.” Sita was shocked. She said, “Alas, dear children! On account of you, the dynasty itself has been tarnished. Don’t delay further. Prepare for my immolation, so I may ascend it. I can’t live hereafter.” Sita pleaded for quick action. The sage Valmiki consoled her and imparted some courage. Then, he went with Kusa and Lava to the battle- field and was amazed at what he saw there. He recognised Rama’s chariot and the horses and, finding Rama, fell at his feet. Rama rose in a trice and sat up. Kusa and Lava were standing opposite to him. Valmiki addressed Rama. “Lord! My life has attained fulfilment. O, How blessed am I!” Then, he described how Lakshmana had left Sita alone in the forest and how Sita lived in his hermitage, where Kusa and Lava were born. He said, “Lord! Kusa and Lava are your sons. May the five elements be my witness, I declare that Kusa and Lava are your sons. Rama embraced the boys and stroked their heads. Through Rama’s grace, the fallen monkeys and warriors rose, alive. Lakshmana, Bharatha, and Satrughna caressed and fondled the boys. -

1506LS Eng.P65

1 AS INTRODUCED IN LOK SABHA Bill No. 92 of 2019 THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2019 By SHRI RAVI KISHAN, M.P. A BILL further to amend the Constitution of India. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Seventieth Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. This Act may be called the Constitution (Amendment) Act, 2019. Short title. 2. In the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution, entries 3 to 22 shall be re-numbered as Amendment entries 4 to 23, respectively, and before entry 4 as so re-numbered, the following entry shall of the Eighth Schedule. 5 be inserted, namely:— "3. Bhojpuri.". STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS Bhojpuri language which originated in the Gangetic plains of India is a very old and rich language having its origin in the Sanskrit language. Bhojpuri is the mother tongue of a large number of people residing in Uttar Pradesh, Western Bihar, Jharkhand and some parts of Madhya Pradesh as well as in several other countries. In Mauritius, this language is spoken by a large number of people. It is estimated that around one hundred forty million people speak Bhojpuri. Bhojpuri films are very popular in the country and abroad and have deep impact on the Hindi film industry. Bhojpuri language has a rich literature and cultural heritage. The great scholar Mahapandit Rahul Sankrityayan wrote some of his work in Bhojpuri. There have been some other eminent writers of Bhojpuri like Viveki Rai and Bhikhari Thakur, who is popularly known as the “Shakespeare of Bhojpuri”. Some other eminent writers of Hindi such as Bhartendu Harishchandra, Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi and Munshi Premchand were deeply influenced by Bhojpuri literature. -

Catalogue of Marathi and Gujarati Printed Books in the Library of The

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofmaratOObrituoft : MhA/^.seor,. b^pK<*l OM«.^t«.lT?r>">-«-^ Boc.ic'i vAf. CATALOGUE OF MARATHI AND GUJARATI PRINTED BOOKS IN THE LIBRARY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. BY J. F. BLUMHARDT, TEACHBB OF BENBALI AT THE UNIVERSITY OP OXFORD, AND OF HINDUSTANI, HINDI AND BBNGACI rOR TH« IMPERIAL INSTITUTE, LONDON. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. •» SonKon B. QUARITCH, 15, Piccadilly, "W.; A. ASHER & CO.; KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TKUBNER & CO.; LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. 1892. /3 5^i- LONDON ! FEINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, VD., ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLKBKENWEIL BOAD, E.C. This Catalogue has been compiled by Mr. J. F. Blumhardt, formerly of tbe Bengal Uncovenanted Civil Service, in continuation of the series of Catalogues of books in North Indian vernacular languages in the British Museum Library, upon which Mr. Blumhardt has now been engaged for several years. It is believed to be the first Library Catalogue ever made of Marathi and Gujarati books. The principles on which it has been drawn up are fully explained in the Preface. R. GARNETT, keeper of pbinted books. Beitish Museum, Feb. 24, 1892. PEEFACE. The present Catalogue has been prepared on the same plan as that adopted in the compiler's " Catalogue of Bengali Printed Books." The same principles of orthography have been adhered to, i.e. pure Sanskrit words (' tatsamas ') are spelt according to the system of transliteration generally adopted in the preparation of Oriental Catalogues for the Library of the British Museum, whilst forms of Sanskrit words, modified on Prakrit principles (' tadbhavas'), are expressed as they are written and pronounced, but still subject to a definite and uniform method of transliteration. -

Download Book

PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE THE PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE BEING A LITERAL TRANSLATION OF THE HINDI TEXT OF LALLU LAL KAVI AS EDITED BY THE LATE PROCESSOR EASTWICK, FULLY ANNOTATED AND EXPLAINED GRAMMATICALLY, IDIOMATICALLY AND EXEGETICALLY BY FREDERIC PINCOTT (MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY), AUTHOR OF THE HINDI ^NUAL, TH^AKUNTALA IN HINDI, TRANSLATOR OF THE (SANSKRIT HITOPADES'A, ETC., ETC. WESTMINSTER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. S.W. 2, WHITEHALL GARDENS, 1897 LONDON : PRINTED BY GILBERT AND KIVJNGTON, LD-, ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLEKKENWELL ROAD, E.G. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE IT is well known to aU who have given thought to the languages of India that the or Bhasha as Hindi, the people themselves call is the most diffused and most it, widely important language of India. There of the are, course, great provincial languages the Bengali, Marathi, Panjabi, Gujarat!, Telugu, and Tamil which are immense numbers of spoken by people, and a knowledge of which is essential to those whose lot is cast in the districts where are but the Bhasha of northern India towers they spoken ; high above them both on account of the all, number of its speakers and the important administrative and commercial interests which of attach to the vast stretch territory in which it is the current form of speech. The various forms of this great Bhasha con- of about stitute the mother-tongue eighty-six millions of people, a almost as as those of the that is, population great French and German combined and cover the empires ; they important region hills on the east to stretching from the Rajmahal Sindh on the west and from Kashmir on the north to the borders of the ; the south. -

AP Reports 229 Black Fungus Cases in 1

VIJAYAWADA, SATURDAY, MAY 29, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 RNI No.APENG/2018/764698 Established 1864 Published From VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 193 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable www.dailypioneer.com New DNA vaccine for Covid-19 Raashi Khanna: Shooting abroad P DoT allocates spectrum P as India battled Covid P ’ effective in mice, hamsters 5 for 5G trials to telecom operators 8 was upsetting 12 In brief GST Council leaves tax rate on Delhi will begin AP reports 229 Black unlocking slowly from Monday, says Kejriwal Coronavirus vaccines unchanged n elhi will begin unlocking gradually fungus cases in 1 day PNS NEW DELHI from Monday, thanks to the efforts of the two crore people of The GST Council on Friday left D n the city which helped bring under PNS VIJAYAWADA taxes on Covid-19 vaccines and control the second wave, Chief medical supplies unchanged but Minister Arvind Kejriwal said. "In the The gross number of exempted duty on import of a med- past 24 hours, the positivity rate has Mucormycosis (Black fungus) cases icine used for treatment of black been around 1.5 per cent with only went up to 808 in Andhra Pradesh fungus. 1,100 new cases being reported. This on Friday with 229 cases being A group of ministers will delib- is the time to unlock lest people reported afresh in one day. erate on tax structure on the vac- escape corona only to die of hunger," “Lack of sufficient stock of med- cine and medical supplies, Finance Kejriwal said. -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011 HARI OM March 1st, Swamiji returned from India where he visited holy places and sister branch in Bangalore. And a fruitful trip to Maha Sarovar (West Kolkata) water to celebrate Mahashivatri here in our temple Sunnyvale. Shiva Abhishekham was performed every 3 hrs with milk, yogurt, sugar, juice and other Dravyas. The temple echoed with devotional chanting of Shiva Panchakshari Mantram, Om Namah Shivayah. During day long Pravachan Swamiji narrated 2 special stories. The first one was about Ganga, and why we pour water on top of Shiva Linga and the second one about Bhasmasura. King Sagar performed powerful Ashwamedha Yagna (Horse sacrifice) to prove his supremacy. Lord Indra, leader of the Demi Gods, fearful of the results of the yagna, stole the horse. He left the horse at the ashram of Kapila who was in deep meditation. King Sagar's 60,000 sons (born to Queen Sumati) and one son Asamanja (born to queen Keshini) were sent to search the horse. When they found the horse at Shri N. Swamiji performing Aarthi KapilaDeva's Ashram, they concluded he had stolen it and prepared to attack him. The noise disturbed the meditating Rishi/Sage VISAYA VINIVARTANTE NIRAHARASYA DEHINAH| KapilaDeva and he opened his eyes and cursed the sons of king sagara for their disrespect to such a great personality. Fire emanced RASAVARJAM RASO PY ASYA from their own bodies and they were burned to ashes instantly. Later PARAM DRSTVA NIVARTATE || king Sagar sent his Grandson Anshuman to retreive the horse. -

SEPTEMBER 10, 1991 (Special Piovis/Dn$J Bill 358 (Sh

349 MattMB Under Rule 377 BHADRA 19, .1913 (SAKA) P/acss of WOIShjJ 350 (Special Provisions) 8171 industries, strengthen and widen the exist- Katni and Bina on a shorter and direct route ing flood banks to avert floods and thus save in public interest. the people of this area from recurring losses and release funds from coastal development The existing only train, namely, Ms- fund for the development of coastal area. hakoshal Express runs on a circuitious route thus taking several additional houes Incon- (viI) Need to fill up the vacancle. veniencing the commuters to reach their of managing Director and respective destinations. Moreover, once Chairman In the New Bank started as on Express Train, it has been of india urgently reduced to a passenger train stopping at various small stations and runs in variably SHRt MORESHWAR SAVE (Auran- late and is always packed beyond its capac- gabad): Sir, the New Bank of India a nation- ity alised ban~ has suffered a Joss of approxi- mately Rs. 10 crore in the financial year Thus, there is every justification for a 1989-90. It is learnt that the loss for the new train. I would, therefore, urge upon the financial year 1990-91. is even higher. Railway Minister to make a statement, re- garding introduction of much a train during One of the major reasons attributable the current session itself. to this is the vacant posts of the Chairman and Managing Director since long. For the last 1 112 years, one of the Executive Direc- tors is heading the bank. The Reserve Bank 13.16 hr.