The Battle of Tannenberg from AFIO's the INTELLIGENCER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German Fear of Russia Russia and Its Place Within German History

The German Fear of Russia Russia and its place within German History By Rob Dumont An Honours Thesis submitted to the History Department of the University of Lethbridge in partial fulfillment of the requirements for History 4995 The University of Lethbridge April 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1-7 Chapter 1 8-26 Chapter 2 27-37 Chapter 3 38-51 Chapter 4 39- 68 Conclusion 69-70 Bibliography 71-75 Introduction In Mein Kampf, Hitler reflects upon the perceived failure of German foreign policy regarding Russia before 1918. He argues that Germany ultimately had to prepare for a final all- out war of extermination against Russia if Germany was to survive as a nation. Hitler claimed that German survival depended on its ability to resist the massive faceless hordes against Germany that had been created and projected by Frederick the Great and his successors.1 He contends that Russia was Germany’s chief rival in Europe and that there had to be a final showdown between them if Germany was to become a great power.2 Hitler claimed that this showdown had to take place as Russia was becoming the center of Marxism due to the October Revolution and the founding of the Soviet Union. He stated that Russia was seeking to destroy the German state by launching a general attack on it and German culture through the introduction of Leninist principles to the German population. Hitler declared that this infiltration of Leninist principles from Russia was a disease and form of decay. Due to these principles, the German people had abandoned the wisdom and actions of Frederick the Great, which was slowly destroying German art and culture.3 Finally, beyond this expression of fear, Hitler advocated that Russia represented the only area in Europe open to German expansion.4 This would later form the basis for Operation Barbarossa and the German invasion of Russia in 1941 in which Germany entered into its final conflict with Russia, conquering most of European 1 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1943, originally published 1926), 197. -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

Primary Source and Background Documents D

Note: Original spelling is retained for this document and all that follow. Appendix 1: Primary source and background documents Document No. 1: Germany's Declaration of War with Russia, August 1, 1914 Presented by the German Ambassador to St. Petersburg The Imperial German Government have used every effort since the beginning of the crisis to bring about a peaceful settlement. In compliance with a wish expressed to him by His Majesty the Emperor of Russia, the German Emperor had undertaken, in concert with Great Britain, the part of mediator between the Cabinets of Vienna and St. Petersburg; but Russia, without waiting for any result, proceeded to a general mobilisation of her forces both on land and sea. In consequence of this threatening step, which was not justified by any military proceedings on the part of Germany, the German Empire was faced by a grave and imminent danger. If the German Government had failed to guard against this peril, they would have compromised the safety and the very existence of Germany. The German Government were, therefore, obliged to make representations to the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias and to insist upon a cessation of the aforesaid military acts. Russia having refused to comply with this demand, and having shown by this refusal that her action was directed against Germany, I have the honour, on the instructions of my Government, to inform your Excellency as follows: His Majesty the Emperor, my august Sovereign, in the name of the German Empire, accepts the challenge, and considers himself at war with Russia. -

To End All Wars Manual EBO

EPILEPSY WARNING PLEASE READ THIS NOTICE BEFORE PLAYING THIS GAME OR BEFORE ALLOWING YOUR CHILDREN TO PLAY. Certain individuals may experience epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when subjected to strong, flashing lights for long periods of time. Such individuals may therefore experience a seizure while operating computer or video games. This can also affect individuals who have no prior medical record of epilepsy or have never previously experienced a seizure. If you or any family member has ever experienced epilepsy symptoms (seizures or loss of consciousness) after exposure to flashing lights, please consult your doctor before playing this game. Parental guidance is always suggested when children are using a computer and video games. Should you or your child experience dizziness, poor eyesight, eye or muscle twitching, loss of consciousness, feelings of disorientation or any type of involuntary movements or cramps while playing this game, turn it off immediately and consult your doctor before playing again. PRECAUTIONS DURING USE: • Do not sit too close to the monitor. • Sit as far as comfortably possible. • Use as small a monitor as possible. • Do not play when tired or short on sleep. • Take care that there is sufficient lighting in the room. • Be sure to take a break of 10-15 minutes every hour. USE OF THIS PRODUCT IS SUBJECT TO ACCEPTANCE OF THE SINGLE USE SOFTWARE LICENSE AGREEMENT CONTENTS WARNING 1 Fixed Units 32 INTRODUCTION 2 Command Chain 32 Leadership 37 INSTALLATION 3 Promoting & Relieving System Requirements 3 -

The Commandant's Introduction

The Commandants Introduction By Michael H. Clemmesen his issue of the Baltic Defence Re- It seems now to have been generally members seem to have realised this fact. view marks a change in the editorial recognized that the Alliance has to be To succeed, the transformation must line that is symbolised by the changed reformed thoroughly to remain relevant take the alliance forward and change it cover. The adjustment is not only caused to the leading member state. The U.S.A., from being a reactive self-defensive alli- by the fact that the three Baltic states have involved as she is in the drawn-out War ance. The outlined new NATO is a po- succeeded in being invited to NATO as Against Terror that was forced upon her litically much more demanding, divisive, well as to the EU and now have to adapt by the 11 September 2001 attacks, is not and risky framework for military co-op- to the new situation. It is also based on impressed by the contribution from most eration. Its missions will include opera- the realisation that the two organisations of the European allies. Only a small tions of coercion like the one against will change their character when the inte- progress has been made in the Yugoslavia with regard to Kosovo as well gration of the new members takes place. enhancement of the force structures of as pre-emptive Out-of-NATO area crisis The implementation of the new editorial the European members since the 1999 response operations military activism line will only come gradually. -

World War I Unit #1 Organiser in Europe in 1914”

Knowledge “War was inevitable Year 8 World War I Unit #1 Organiser in Europe in 1914”. Causes of Tension and War Archduke Franz Ferdinand Gavrilo Princip Key Terms • A member of the Austrian Royal • Gavrilo Princip was Family - nephew of Emperor Franz born in Bosnia in Militarism Building up military forces. Military Josef 1894, the son of a The army and navy – • Heir to the Austrian throne (next in postman. Agreements between fighting forces line to be the Emperor / ruler of • He became a Alliances countries to support each Alliances Austria-Hungary) member of the Black other in war. Promises between • Not very well liked in Austria Hand – a Serbian countries to support Pride and devotion to one’s • Married to Sophie and had three terrorist organisation Nationalism each other country. Children which wanted to hurt Colony • Was sent on a Royal tour to Sarajevo, Austria and get it out The countries that make One country taking over the capital of Bosnia – a county which of Bosnia. up an Empire Imperialism another country Austria has just taken over. • Planned to The Balkans economically and politically. • Assassinated on June 28, 1914 by assassinate Franz Serbia and Bosnia Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand The murder of Franz Nationalism Assassination Ferdinand. Profound pride in ones country Timeline of 1914 – events leading up to the start of WW1 Competition Rivalry over trade. Slav An ethnic group from June 28 - Archduke Franz Ferdinand, prince to the Austria- Russia Alliances Hungary throne, is assassinated in Sarajevo by a Serbian named Annex In 1914 there were two main power blocks / alliances: Gavrilo Princip. -

East Prussia ‘14

Designer Notes: East Prussia ‘14 In the middle of August 1914, the world's attention was focused directly on the Western Front where German armies were sweeping into Belgium and France. On the Eastern Front however, the Russians were on the offensive into East Prussia, an important agricultural region of the Prussian homeland, and the gateway to Berlin. The Russians planned a two pronged invasion into East Prussia: one army approaching from the Niemen River to the east and one army approaching from the Narew River to the south, both aimed at outflanking German forces located therein, and the eventual capture of the strategic city of Königsberg. In their way stood a single German army, two resolute commanders, and a well developed rail network. By the time the campaign was over both Russian armies would be almost completely destroyed and thrown out of East Prussia and the campaign itself would go on to become one of the most studied and celebrated victories in warfare. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 The Belligerents ................................................................................................................. 7 The German Army .......................................................................................................... 7 Summary of Capabilities............................................................................................. 7 Organization ............................................................................................................... -

C:/Users/User/Desktop/2017-08-16 Tannenberg Booklet 6 Seiten BGG

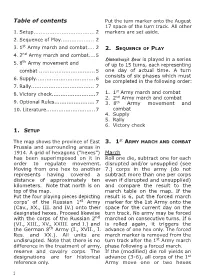

Table of contents Put the turn marker onto the August 17 space of the turn track. All other 1. Setup................................... 2 markers are set aside. 2. Sequence of Play................... 2 st 3. 1 Army march and combat.... 2 2. SEQUENCE OF PLAY 4. 2nd Army march and combat....5 th Hindenburg’s Hour is played in a series 5. 8 Army movement and of up to 15 turns, each representing combat ................................ 5 one day of actual time. A turn consists of six phases which must 6. Supply..................................6 be completed in the following order: 7. Rally.................................... 7 st 8. Victory check.........................7 1. 1 Army march and combat 2. 2nd Army march and combat 9. Optional Rules....................... 7 3. 8th Army movement and 10. Literature............................ 7 combat 4. Supply 5. Rally 6. Victory check 1. SETUP The map shows the province of East 3. 1st ARMY MARCH AND COMBAT Prussia and surrounding areas in 1914. A grid of hexagons (“hexes”) March has been superimposed on it in Roll one die, subtract one for each order to regulate movement. disrupted and/or unsupplied (see Moving from one hex to another 7.) corps in the army (do not represents having covered a subtract more than one per corps distance of approximately ten even if disrupted and unsupplied) kilometers. Note that north is on and compare the result to the top of the map. march table on the map. If the Put the four playing pieces depicting result is 6, put the forced march corps’ of the Russian 1st Army marker for the 1st Army onto the (Cav., XX., III. -

2018 • Vol. 2 • No. 2

THE JOURNAL OF REGIONAL HISTORY The world of the historian: ‘The 70th anniversary of Boris Petelin’ Online scientific journal 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 Cherepovets 2018 Publication: 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 JUNE. Issued four times a year. FOUNDER: Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education ‘Cherepovets State University’ The mass media registration certificate is issued by the Federal Service for Supervi- sion of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor). Эл №ФС77-70013 dated 31.05.2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: O.Y. Solodyankina, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) DEPUTY EDITORS-IN-CHIEF: A.N. Egorov, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) E.A. Markov, Doctor of Political Sciences (Cherepovets State University) B.V. Petelin, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) A.L. Kuzminykh, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Vologda Institute of Law and Economics, Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia) EDITOR: N.G. MELNIKOVA COMPUTER DESIGN LAYOUT: M.N. AVDYUKHOVA EXECUTIVE EDITOR: N.A. TIKHOMIROVA (8202) 51-72-40 PROOFREADER (ENGLISH): N. KONEVA, PhD, MITI, DPSI, SFHEA (King’s College London, UK) Address of the publisher, editorial office and printing-office: 162600 Russia, Vologda region, Cherepovets, Prospekt Lunacharskogo, 5. OPEN PRICE ISSN 2587-8352 Online media 12 standard published sheets Publication: 15.06.2018 © Federal State Budgetary Educational 1 Format 60 84 /8. Institution of Higher Education Font style Times. ‘Cherepovets State University’, 2018 Contents Strelets М. B.V. Petelin: Scientist, educator and citizen ............................................ 4 RESEARCH Evdokimova Т. Walter Rathenau – a man ahead of time ............................................ 14 Ermakov A. ‘A blood czar of Franconia’: Gauleiter Julius Streicher ...................... -

Ronald Macarthur Hirst Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4f59r673 No online items Register of the Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Processed by Brad Bauer Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Ronald MacArthur 93044 1 Hirst papers Register of the Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Brad Bauer Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Elizabeth Konzak and David Jacobs © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Dates: 1929-2004 Collection number: 93044 Creator: Hirst, Ronald MacArthur, 1923- Collection Size: 102 manuscript boxes, 4 card files, 2 oversize boxes (43.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: The Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers consist largely of material collected and created by Hirst over the course of several decades of research on topics related to the history of World War II and the Cold War, including the Battle of Stalingrad, the Allied landing at Normandy on D-Day, American aerial operations, and the Berlin Airlift of 1948-1949, among other topics. Included are writings, correspondence, biographical data, notes, copies of government documents, printed matter, maps, and photographs. Physical location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English, German Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copiesof audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. -

2018 MS NHBB National Bowl Round 8

2018 NHBB Middle School National Bowl 2017-2018 Round 8 Round 8 First Quarter (1) This man argued that \history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce" and he panned religion as the \opiate of the masses" in his critique of Hegel's philosophy. This man declared that a \spectre is haunting Europe" and argued that all capitalist societies would eventually fall in his most famous work, co-authored with Friedrich Engels. For ten points, name this author of the Communist Manifesto. ANSWER: Karl Marx (2) This humanitarian established a Missing Soldiers office in Gallery Place that was \lost" for over 100 years. The first international office of an organization founded by this woman was established in the aftermath of the Hamidian massacre. Benjamin Butler appointed this person as the \lady in charge" of the hospitals for the Army of the James. For ten points, name this nurse who founded the American Red Cross. ANSWER: Clara Barton (3) This dynasty legendarily began when Ku's wife stepped into a giant footprint left by Shangdi. This dynasty's government gradually became weaker during the Spring and Autumn period in its final years. It created the Mandate of Heaven to justify its rule, the longest of any Chinese dynasty. For ten points, name this dynasty that eventually fell apart at the start of the Warring States period. ANSWER: Zhou dynasty (4) This battle resulted in the suicide of Alexander Samsonov after the encirclement of the Second Army. Despite being fought near Allenstein, this battle was renamed to evoke the sense of avenging a 1410 defeat of the Teutonic Knights. -

Cittaslow Cities Varmia Masuria Powiśle

quality of life CITTASLOW CITIES VARMIA MASURIA POWIŚLE www.cittaslowpolska.pl Mamonowo Gronowo Grzechotki Bagrationowsk Braniewo RUS Żeleznodorożnyj Bezledy Gołdap Gołdap Zalew wiślany Górowo Iławeckie PODLASKIE Pieniężno Bartoszyce Węgorzewo ELBLĄG Korsze Lidzbark Orneta Warmiński Bisztynek Kętrzyn Giżycko Pasłęk Reszel Olecko POMORSKIE Dobre Miasto Jeziorany Ryn Morąg Biskupiec Mrągowo EŁK Orzysz Mikołajki Barczewo OLSZTYN Ostróda Olsztyn Pisz Ruciane-Nida Biała Piska Iława Olsztynek Warszawa Szczytno Lubawa Kolno Nowe Miasto Lubawskie MAZOWIECKIE KU AJ WS Nidzica K O-POMORSKIE Lidzbark Welski Brodnica Działdowo Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship OSTROŁ¢KA VARMIA MASURIA POWIŚLE MASURIA VARMIA CITTASLOW CITIES CITTASLOW www.cittaslowpolska.pl Olsztyn 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS INVITATION Invitation 3 There are many beautiful, vibrant tourist destinations in the Why Cittaslow? 4 world. There are, however, also many places where there are not so many tourists. In today’s big world, we are busy and restless, Attractions of Varmia, Masuria and Powiśle 6 chasing time to meet the most important needs. But there are, however, places where life seems to be calmer, where there is more Cittaslow Cities time for reflection. They are small towns located mostly away from main roads, away from big industry and sometimes from the surfeit Barczewo 10 of modernity. Today, when money makes our world go round, when work Biskupiec 15 takes most of our time, we often want to escape to an oasis of peace and tranquility, where life is slower. This is reflected in our Bisztynek 20 various actions: working in big cities – we want to live outside them, working on weekdays – we want to spend weekends close to Dobre Miasto 26 nature, working in noise – we want peace.